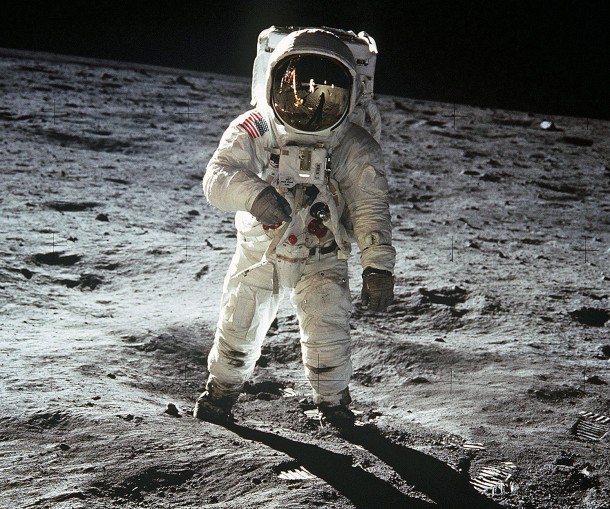

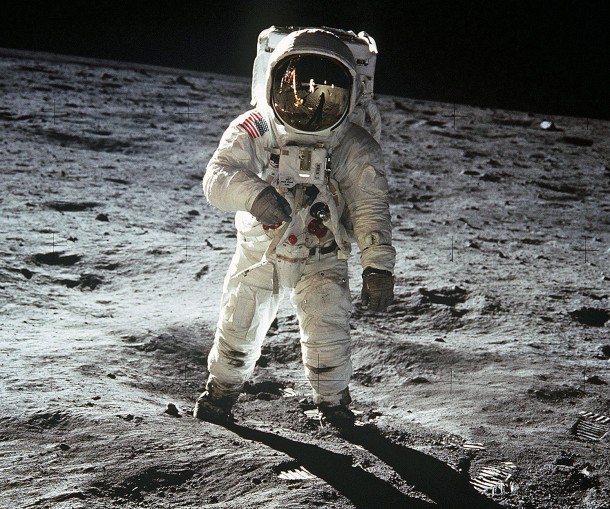

Fifty-one years ago today, the United States of America landed two men on the surface of the Moon. This feat marked the first time in history that men from the planet Earth set foot on another celestial body in the solar system.

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle landed in the Sea of Tranquility region of the Moon on Sunday, 20 July 1969 at 20:17:40 UTC. Less than seven hours later, Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. became the first human beings to walk upon Earth’s closest neighbor. Fellow crew member Michael Collins orbited high overhead in the Command Module Columbia.

As Apollo 11 commander, Neil A. Armstrong was accorded the privilege of being the first man to step foot upon the Moon. As he did so, Armstrong spoke these words: “That’s one small step for Man; one giant leap for Mankind”. He had intended to say: “That’s one small step for ‘a’ man; one giant leap for Mankind”.

Armstrong and Aldrin explored their Sea of Tranquility landing site for about two and a half hours. Total lunar surface stay time was 22 hours and 37 minutes. The Apollo 11 crew left a plaque affixed to one of the legs of the Lunar Module’s descent stage which read: “Here Men From the Planet Earth First Set Foot Upon the Moon; July 1969, A.D. We Came in Peace for All Mankind”.

Following a successful lunar lift-off aboard the Eagle, Armstrong and Aldrin rejoined Collins in lunar orbit. Approximately seven hours later, the Apollo 11 crew rocketed out of lunar orbit to begin the quarter million mile journey back to Earth. Columbia splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean at 16:50:35 UTC on Thursday, 24 July 1969. Total mission time was 195 hours, 18 minutes, and 35 seconds.

With completion of the flight of Apollo 11, the United States of America fulfilled President John F. Kennedy’s 25 May 1961 call to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth before the decade of the 1960’s was out. It had taken 2,982 demanding days, a number of lives, and a great deal of national treasure to do so. “Mission Accomplished, Mr. President”.

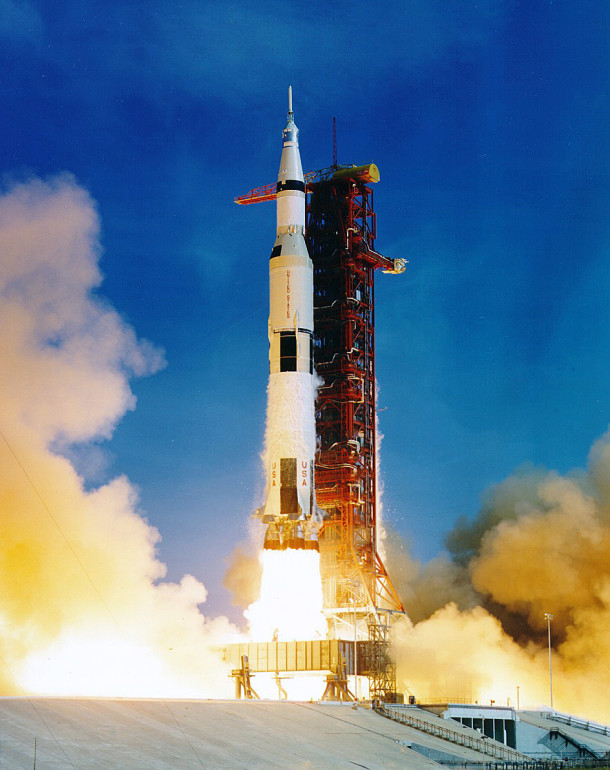

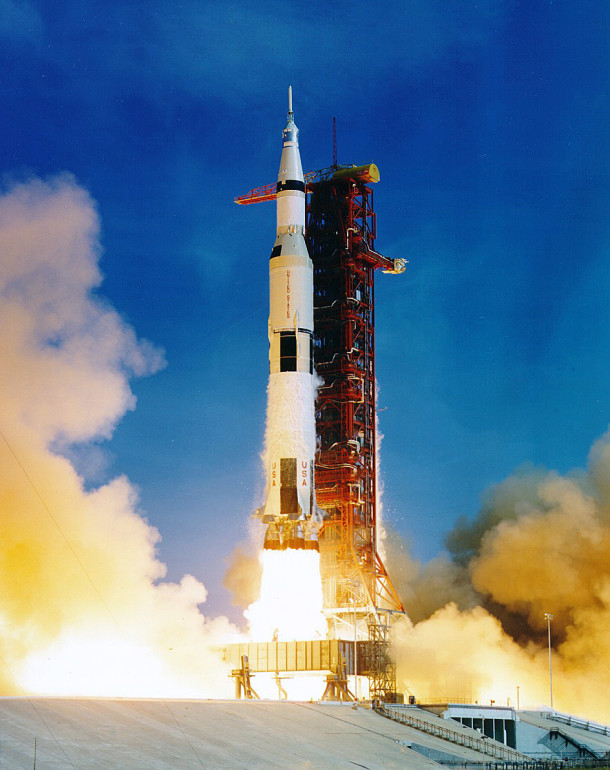

Fifty-one years ago today, the epic flight of Apollo 11, the first mission to land men on the Moon, began with launch from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at Merritt Island, Florida. Nearly 1-million people gathered around America’s famous space complex to witness the historic event. An estimated 1-billion viewers worldwide watched the proceedings on television.

The names of the Apollo 11 crew are now legend: Mission Commander Neil A. Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins. Each astronaut was making his second spaceflight.

The overall Apollo 11 spacecraft weighed over 100,000 pounds and consisted of 3 major components: Command Module, Service Module, and Lunar Excursion Module (LEM). Out of American history came the names used to distinguish two of these components from one another. The Command Module was named Columbia, the feminine personification of America, while the Lunar Excursion Module received the appellation Eagle in honor of America’s national bird.

The Apollo-Saturn V launch stack measured 363-feet in length, had a maximum diameter of 33-feet, and weighed 6.7-milllion pounds at ignition of its five F-1 engines. The vehicle rose from the Earth on 7.7-million pounds of lift-off thrust.

The acoustic energy produced by the Saturn’s first stage propulsion system was unlike anything in common experience. The sound produced was like intense, continuous thunder even miles away from the launch point. Ground and structure shook disturbingly and a person’s lungs vibrated within their chest cavity.

Lift-off of Apollo 11 (AS-506) from KSC’s LC-39A occurred at 13:32 UTC on Wednesday, 16 July 1969. The target for the day’s launch, the Moon, was 218,096 miles distant from Earth. It took 12 seconds just for the massive Apollo 11 launch vehicle to clear the launch tower. However, a scant 12 minutes later, the Apollo 11 spacecraft was safely in low earth orbit (LEO) traveling at 17,500 miles per hour.

Following checkout in earth orbit, trans-lunar injection, and earth-to-moon coast, Apollo 11 entered lunar orbit nearly 76 hours after lift-off. Now, the big question: Would they make it? Even Apollo 11’s Command Module Pilot, Michael Collins, estimated that the chance of a successful lunar landing on the first attempt was only 50/50. The answer would soon come. History’s first lunar landing attempt was now only 24 hours away.

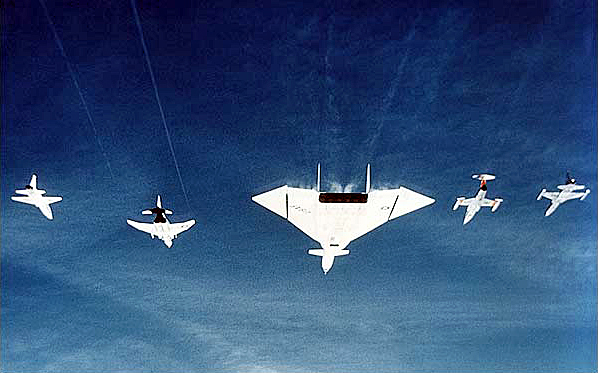

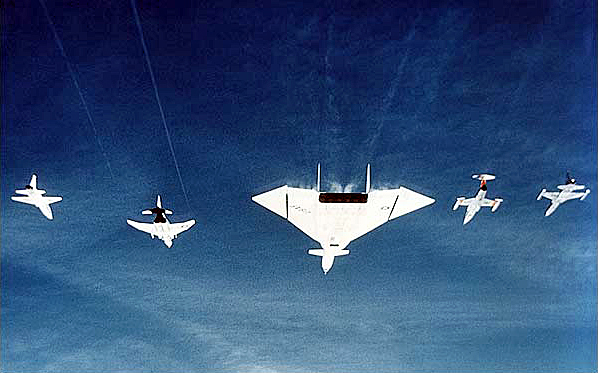

Thirty-one years ago this month, the USAF/Northrop B-2 Stealth Strategic Bomber flew for the first time. The aircrew for the B-2’s maiden trip upstairs included Northrop B-2 Division Chief Test Pilot Bruce J. Hinds (command pilot) and B-2 Combined Test Force Commander USAF Col. Richard S. Couch (co-pilot).

The B-2 traces it lineage to a variety of Northrop flying wing aircraft including the piston-powered YB-35 and jet-propelled YB-49. These 1940’s-era experimental aircraft served as important stepping stones in the evolution of large flying wing technology.

An all-wing aircraft represents an aerodynamically-optimal configuration from the standpoint of high lift, low drag and therefore high lift-to-drag ratio. These favorable aerodynamic attributes translate to high levels of range performance and load-carrying capability. In addition, the type’s high aspect ratio and slim profile provide for more favorable low observable characteristics than traditional fuselage-wing-empennage aircraft geometries.

Arguably the most challenging aspects of creating an all-wing aircraft have to do with flight control and handling qualities. The crash of the second YB-49 flying wing in June of 1948 underscored the insufficiency of aerospace technology at that time to handle these design challenges. It was not until the advent of modern flight control avionics during the 1980’s that the full potential of a flying wing aircraft would be realized.

The B-2 is only 69 feet in length, but has a wing span of 172 feet and a wing area of 5,140 square feet. Gross take-off and empty weights are 336,500 lbs and 158,000 lbs, respectively. Embedded within the wings are a quartet of fuel-efficient F118-GE-100 turbofan engines, each generating 17,300 lbs of thrust. The aircraft has a top speed of about Mach 0.85, an unrefueled range of 6,000 nautical miles and a service ceiling of 50,000 feet. Maximum ordnance load is 50,000 lbs.

B-2 AV-1 (Spirit of America; S/N 82-1066) took-off for the first time from Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California on Monday, 17 July 1989. Supported by F-16 chase aircraft, the majestic flying wing flew a 2 hour 12 minute test mission which concluded with a landing at nearby Edwards Air Force Base. As a first flight precaution, the entire mission was flown with the landing gear down.

The first B-2 airframe to enter the operational inventory was AV-8, the Spirit of Missouri (S/N 88-0329). It did so on 31 March 1994. While initial plans called for a production run of 132 aircraft, only 21 B-2 airframes were actually built. With the 2008 loss of the Spirit of Kansas shortly after take-off from Andersen Air Force Base in Guam, 20 of these aircraft remain in active service today.

Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri serves as Air Force’s home for the B-2. From there, the majestic flying wing has flown a multitude of global strike missions to deliver a variety of ordnance with pinpoint accuracy. To date, the B-2 has successfully engaged targets in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya. The B-2 is truly a technological marvel and a national defense asset. As such, it may be expected to be a vital part of the Air Force’s active inventory for decades to come.

Thirty-eight years ago today, the Space Shuttle Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base to successfully conclude the fourth orbital mission of the Space Transportation System. Columbia’s return to earth added a special and patriotic touch to the celebration of our nation’s 206th birthday.

STS-4 was NASA’s fourth Space Shuttle mission in the first fourteen months of Shuttle orbital flight operations. The two-man crew consisted of Commander Thomas K. Mattingly, Jr. and Pilot Henry W. Hartsfield who were both making their first Shuttle orbital mission. STS-4 marked the last time that a Shuttle would fly with a crew of just two.

STS-4 was launched from Cape Canaveral’s LC-39A on Sunday, 27 June 1982. Lift-off was exactly on-time at 15:00:00 UTC. This mission stands as the first occasion in which a Space Shuttle launch would occur precisely on-time. The Columbia orbiter weighed a hefty 241,664 lbs at launch.

Mattingly and Hartsfield spent a little over seven (7) days orbiting the Earth in Columbia. The orbiter’s cargo consisted of the first Getaway Special payloads and a classified US Air Force payload of two missile launch-detection systems. In addition, a Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES) and the Mono-Disperse Latex Reactor (MLR) were flown for a second time.

The Columbia crew conducted a lightning survey using manual cameras and several medical experiments. Mattingly and Hartsfield also maneuvered the Induced Environment Contamination Monitor (IECM) using the Orbiter’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS). The IECM was used to obtain information on gases and particles released by Columbia in flight.

On Sunday, 04 July 1982, retro-fire of the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines started Columbia on its way back to Earth. Touchdown occurred on Edwards Runway 22 at 16:09:31 UTC. This landing marked the first time that an Orbiter landed on a concrete runway. (All three previous missions had landed on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards.) Columbia made 112 complete orbits and traveled 2,537,196 nautical miles during STS-4.

The Space Shuttle was optimistically declared “operational” with the successful conduct of the first four (4) shuttle missions. President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan even greeted the returning STS-4 flight crew on the tarmac.

However, as space history has taught us, manned spaceflight still comes with a level of risk and danger that exceeds that of military and commercial aircraft operations. Despite its unparalleled accomplishments and enduring legacy, the Space Shuttle was never operational in the true and desired sense.

Nineteen years ago this month, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor caused the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit paydirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s historic scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and its crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

Fifty-five years ago this month, Gemini Astronaut Edward H. White II became the first American to perform what in NASA parlance is referred to as an Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA). In everyday terms, it is referred to as a “spacewalk”.

White, Mission Commander James A. McDivitt and their Gemini spacecraft were launched into low Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. The Gemini-Titan IV (GT-4) mission clock started at 15:15:59 UTC on Thursday, 03 June 1965.

On the third orbit, less than five hours after launch, White opened the Gemini IV starboard hatch. He stood in his seat and mounted a camera to capture his historic space stroll. He then cast-off from Gemini IV and became a human satellite.

White was tethered to Gemini IV via a 15-foot umbilical that provided oxygen and communications to his EVA suit. A gold-plated visor on his helmet protected his eyes from the searing glare of the sun. The spacewalking astronaut was also outfitted with a hand-held maneuvering unit that used compressed oxygen to power its small thrusters. And, like any good tourist, White also took along a camera to photograph the event.

Ed White had the time of his all-too-brief life in the 22 minutes that he walked in space. The sight of the earth, the spacecraft, the sun, the vastness of space, the freedom of movement all combined to make him excitedly exclaim at one point, “I feel like a million dollars!”.

Presently, it was time to get back into the spacecraft. But, couldn’t he just stay outside a little longer? NASA Mission Control and Commander McDivitt were firm. It was time to get back in; now! He grudgingly complied with the request/order, plaintively lamenting: “It’s the saddest moment of my life!”

As Ed White got back into his seat, he and McDivitt struggled to lock the starboard hatch. Both men were exhausted, but ebullient as they mused about the successful completion of America’s first space walk.

Gemini IV would eventually orbit the Earth 62 times before splashing-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 17:12:11 GMT on Sunday, 07 June 1965. The 4-day mission was another milestone in America’s quest for the moon.

The mission was over and yet Ed White was still a little tired. But then, that was really quite easy to understand. In the time that he was spacewalking outside the spacecraft, Gemini IV had traveled almost a third of the way around the Earth.

Fifty-four years ago today, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Barstow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Nineteen years ago today, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet (Supersonic Combustion RAMJET) propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor or so-called “smoking gun” cause was responsible for the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit pay dirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the pioneering scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s history-making scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and her crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

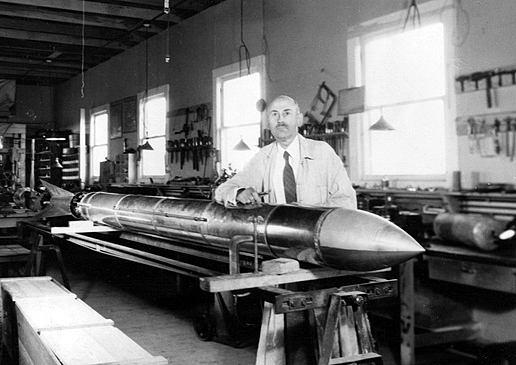

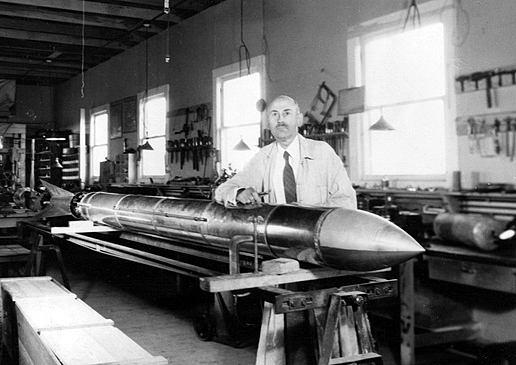

Eighty-five years ago this month, pioneering rocket scientist Robert H. Goddard and staff fired a liquid-fueled rocket to a record altitude of 7,500 feet above ground level. The record-setting flight took place at Roswell, New Mexico.

Robert Hutchings Goddard was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on Thursday, 05 October 1882. He was enamored with flight, pyrotechnics, rockets and science fiction from an early age. By the time he was 17, Goddard knew that his life’s work would combine all of these interests.

Goddard was a sickly youth, but spent his well moments as a voracious reader of all manner of science-oriented literature. He graduated in 1904 from South High School in Worcester as the valedictorian of his class. He matriculated at Worcester Polytechnic and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in physics in 1908. A Master of Science degree and Ph.D. from Worcester’s Clark University followed in 1910 and 1911, respectively.

Goddard spent the next eight years of his life working on numerous propulsion and rocket-related projects. Then, in 1919, he published his now-famous scientific treatise entitled A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes. In that paper, the press glommed on to Goddard’s passing mention that a multi-staged rocket could conceivably fly all the way to the Moon.

Goddard was roundly ridiculed for his fanciful prognostications about Moon flight. The New York Times was especially derogatory in its estimation of Goddard’s ideas and accused him of junk science. A Times editorial even criticized Goddard for his ”misconception” that a rocket could produce thrust in the vacuum of space.

Even the U.S. government largely ignored Goddard. This scornful treatment to which Goddard was subject hurt him profoundly. So much so that he spent the remainder of his life alienated from the denizens of the press as well as the dolts of governmental employ.

Despite the blow to his professional reputation, Goddard resolutely pressed on with his rocket research. Indeed, after more that five years of intense development effort, Goddard and his staff launched the first liquid-fueled rocket on Tuesday, 16 March 1926 in Auburn, Massachusetts. The flight duration was short (2.5 seconds) and the peak altitude tiny (41 feet), but Goddard proved that liquid rocket propulsion was feasible.

Goddard’s liquid-fueled rocket testing would ultimately lead him from the countryside of New England to the desert of the Great South West. With financial support from Harry Guggenheim and the public backing of Charles Lindbergh, Goddard transferred his testing activities to Roswell, New Mexico in 1930. He would continue liquid-fueled rocket testing there until May 1941.

On Friday, 31 May 1935, experimental rocket flight A-8 took to the air from Goddard’s Roswell, New Mexico test site at 1430 UTC. Roughly 15 feet in length and weighing approximately 90 pounds at lift-off, the 9-inch diameter A-8 achieved a maximum altitude of 7,500 feet (1.23 nautical miles) above the desert floor. Only a flight in March of 1937 would go higher (9,000 feet).

Robert Goddard was ultimately credited with 214 U.S. patents for his rocket development work. Only 83 were awarded in his life time. His far-reaching inventions included rocket nozzle design, regeneratively cooled rocket engines, turbo-pumps, thrust vector controls, gyroscopic control systems and more.

Goddard died at the age of 62 from throat cancer in Baltimore, Maryland on Friday, 10 August 1945. Many years would pass before the full import of his accomplishments was comprehended. Then, the posthumously-bestowed recognition came in torrents. In 1959, Congress issued a special gold medal in Goddard’s honor. The Goddard Spaceflight Center was so named by NASA in 1959 as well. Many more such bestowals followed.

Perhaps the most meaningful of the recognitions ever accorded Robert Hutchings Goddard occurred 24 years after his passing. It was in connection with the first manned lunar landing in July of 1969. And it was poetic not only in terms of its substance and timing, but more particularly in light of the source from whence the recognition came.

A terse statement in the New York Times corrected a long-standing injustice. It read: “Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Issac Newton in the 17th century, and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.”

Fifty-seven years ago this month, NASA Astronaut Leroy Gordon Cooper successfully returned to earth after completing 22 orbits of the home planet. Designated Mercury-Atlas No. 9 (MA-9), Cooper’s flight was the final orbital space mission of the fabled Mercury Program.

Cooper’s eventful space mission began with lift-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-14 at 13:04 hours UTC on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. Splashdown of his Faith 7 spacecraft occurred 70 miles southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, 16 May 1963. Mission total elapsed time was 34 hours 19-minutes 49-seconds.

While the first 19 orbits of the MA-9 mission were mostly unremarkable, the final three orbits severely tested Cooper’s mettle and piloting skills.

By the time that he manually initiated ripple-firing of the retro motors at the end of the 22nd orbit, Cooper was flying a dead spacecraft. The electrical system was not functioning, the environmental control system was saturated with carbon dioxide, and even the mission clock was inoperative. Temperatures in the spacecraft exceeded 130F.

Cooper had to align his spacecraft for retro-fire using the horizon as a reference, used a watch for timing, and manually operated the reaction control system to counter dangerous spacecraft oscillations during the retro burn.

Cooper also manually controlled Faith 7 during entry and initiated deployment of the drogue and main parachutes.

Incredibly, Cooper landed within 5 miles of the recovery ship USS Kearsarge. In so doing, he established the record for the most accurate landing in the Mercury Program. Gordon Cooper was the last American astronaut to orbit the Earth alone.