Forty years ago today, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., and Michael Collins arrived back at the Johnson Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas following their epic journey to and safe return from the Moon.

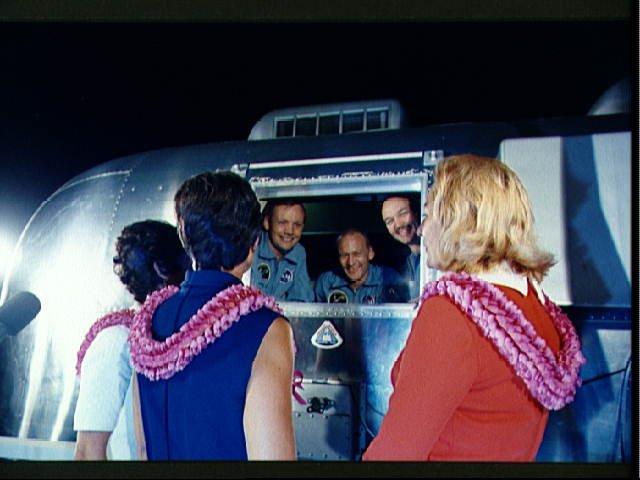

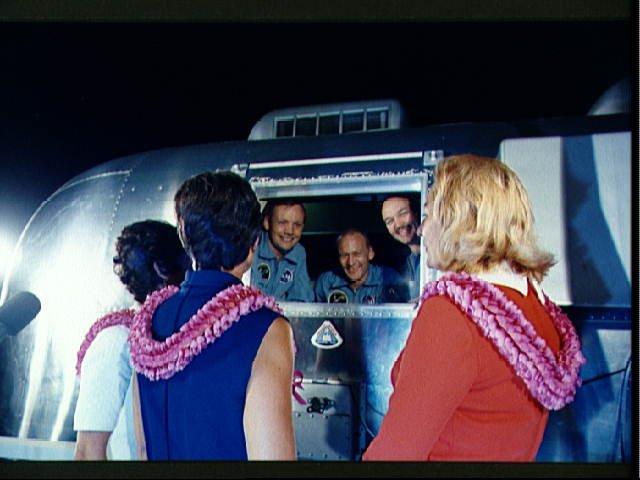

Following splashdown in the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, 24 July, 1969, the Apollo 11 astronauts and their Command Module Columbia were brought aboard the USS Hornet. Concerned that they would infect Earthlings with lunar pathogens, NASA quarantined the astronauts in the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), which was a converted vacation trailer.

The Hornet steamed for Hawaii and transferred the MQF for airlift to Ellington Air Force Base, Texas. Following landing, the MQF and its heroic occupants were transported to the MSC. Once there, the astronauts and several medical staff were transferred from the MQF to more substantial accomodations known as the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL).

Combined stay time in the MQF and LRL was 21 days. During their forced confinement, Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins debriefed the Apollo 11 mission, rested, and mused about their unforgettable experiences at the Moon.

The Apollo 11 astronauts were released from the LRL on Thursday, 13 August 1969, having never contracted or transmitted a lunar disease.

Forty years ago today, the United States of America landed two men on the surface of the Moon.

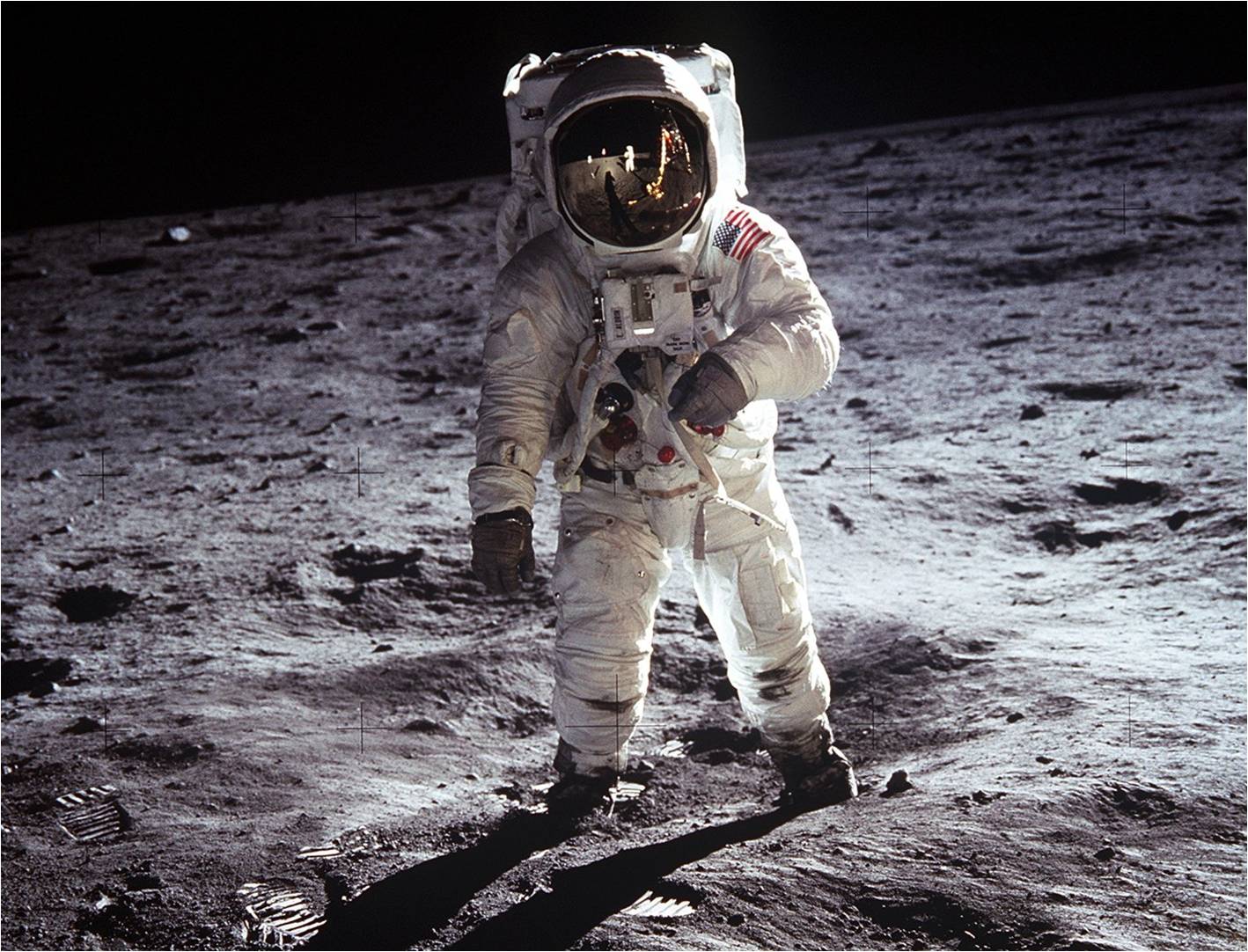

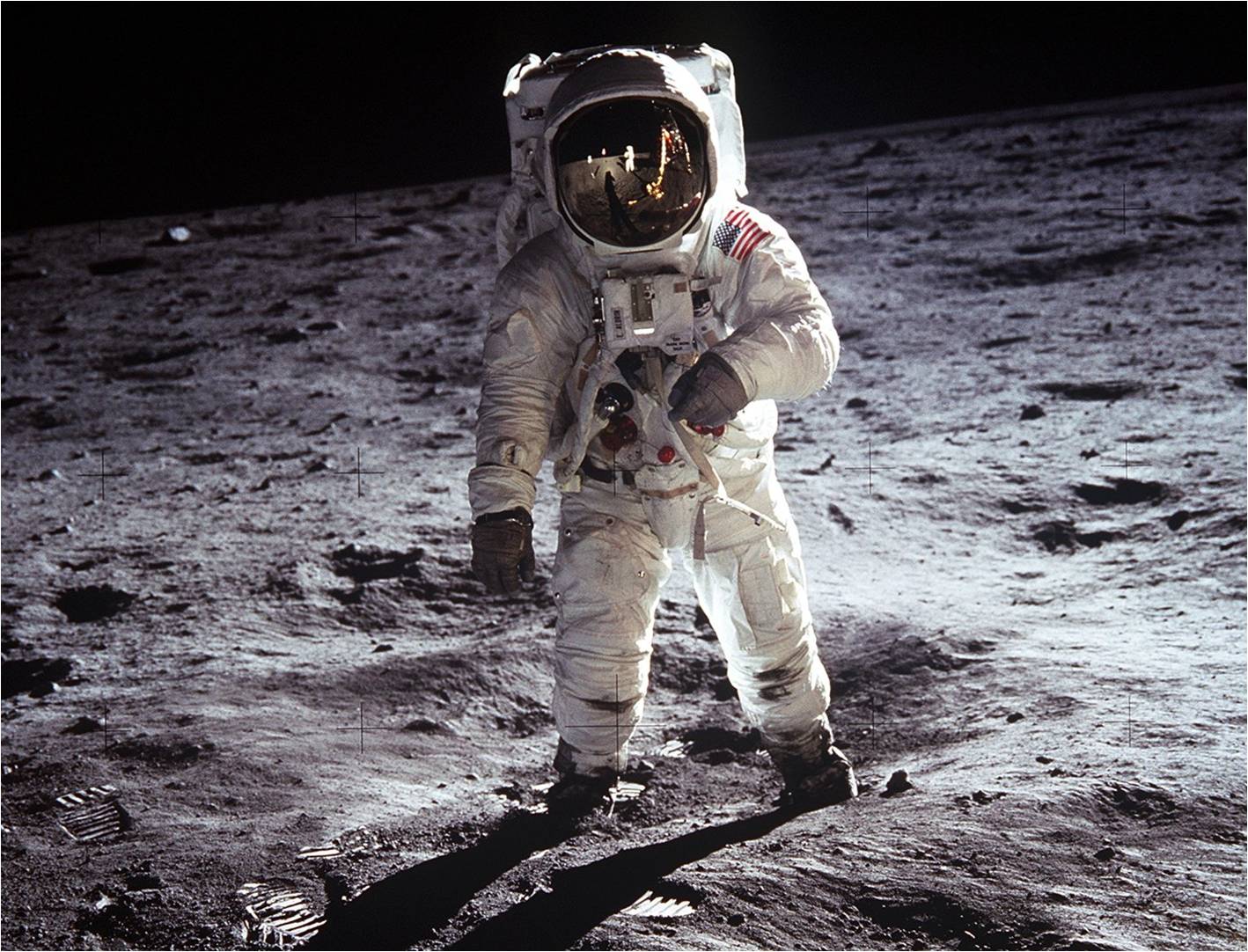

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle landed in Sea of Tranquility region of the Moon on Sunday, 20 July 1969 at 20:17:40 UTC. Less than seven hours later, astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. became the first human beings to walk upon Earth’s closest neighbor. Fellow crew member Michael Collins orbited high overhead in the Command Module Columbia.

As Apollo 11 commander, Neil A. Armstrong was accorded the privilege of being the first man to step foot upon the Moon. As he did so, Armstrong spoke these words: “That’s one small step for Man; one giant leap for Mankind”. He had intended to say: “That’s one small step for ‘a’ man; one giant leap for Mankind”.

Armstrong and Aldrin explored their Sea of Tranquility landing site for about two and a half hours. Total lunar surface stay time was 22 hours and 37 minutes. The Apollo 11 crew left a plaque affixed to one of the legs of the Lunar Module’s descent stage which read: “Here Men From the Planet Earth First Set Foot Upon the Moon; July 1969, A.D. We Came in Peace for All Mankind”.

Following a successful lunar lift-off, Armstrong and Aldrin rejoined Collins in lunar orbit. Approximately seven hours later, the Apollo 11 crew rocketed out of lunar orbit to begin the quarter million mile journey back to Earth. Columbia splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean at 16:50:35 UTC on Thursday, 24 July 1969. Total mission time was 195 hours, 18 minutes, and 35 seconds.

With completion of the flight of Apollo 11, the United States of America fulfilled President John F. Kennedy’s 25 May 1961 call to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth before the decade of the 1960’s was out. It had taken 2,982 demanding days and much national treasure to do so.

Mission Accomplished, Mr. President.

Forty years ago this week, the epic flight of Apollo 11, the first mission to land men on the Moon, began with launch from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at Merritt Island, Florida. Nearly 1-million people gathered around America’s famous space complex to witness the historic event. An estimated 1-billion viewers worldwide watched the proceedings on television.

The names of the Apollo 11 crew are now legend: Mission Commander Neil A. Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins. Each astronaut was making his second spaceflight.

The overall Apollo 11 spacecraft weighed roughly 100,000 pounds and consisted of 3 major components: Command Module, Service Module, and Lunar Excursion Module (LEM). Out of American history came the names used to distinguish two of these components from one another. The Command Module was named Columbia, the feminine personification of America, while the Lunar Excursion Module received the appellation Eagle in honor of America’s national bird.

The Apollo-Saturn V launch stack measured 363-feet in length, had a maximum diameter of 33-feet, and weighed 6.7-milllion pounds at ignition of its five F-1 engines. The vehicle rose from the Earth on 7.7-million pounds of lift-off thrust.

The acoustic energy produced by the Saturn’s first stage propulsion system was unlike anything in common experience. The sound produced was like intense, continuous thunder even miles away from the launch point. Ground and structure shook disturbingly and a person’s lungs vibrated within their chest cavity.

Lift-off of Apollo 11 (AS-506) from KSC’s LC-39A occurred at 13:32 UTC on Wednesday, 16 July 1969. The target for the day’s launch, the Moon, was 218,096 miles distant from Earth. It took 12 seconds just for the massive Apollo 11 launch vehicle to clear the launch tower. However, a scant 12 minutes later, the Apollo 11 spacecraft was safely in low earth orbit (LEO) traveling at 17,500 miles per hour.

Following checkout in earth orbit, trans-lunar injection, and earth-to-moon coast, Apollo 11 entered lunar orbit nearly 76 hours after lift-off. Now, the big question: Would they make it? Even Apollo 11’s Command Module Pilot, Michael Collins, estimated that the chance of a successful lunar landing on the first attempt was only 50/50. The answer would soon come. History’s first lunar landing attempt was now only 24 hours away.

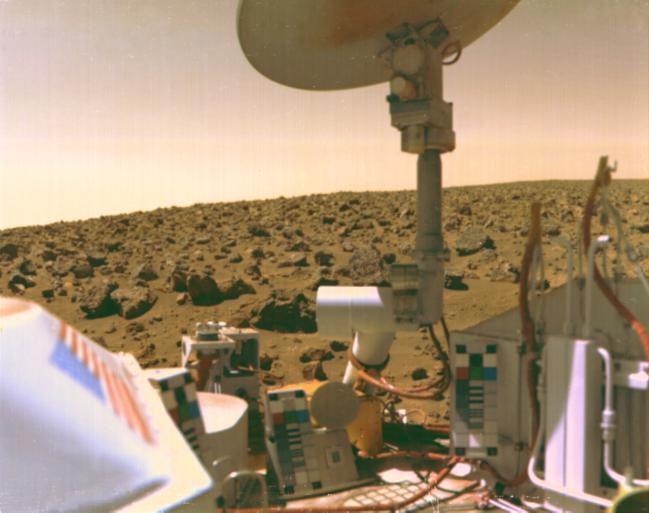

Thirty-three years ago this month, on the seventh anniversary of the first manned lunar landing, Viking I became the first spacecraft to successfully land on the surface of the planet Mars. The primary purpose of the mission was to search for signs of life on the Martian surface.

The Viking I mission began with launch from Earth on Wednesday, 20 August 1975. Lift-off of the Titan IIIE-Centaur launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral, Florida took place at 2122 UTC. The Viking I orbiter-lander payload mass at lift-off was 7,766 lbs.

After chasing Mars for 11 months and 500,000,000 miles, Viking I entered Martian orbit on Saturday, 19 June 1976. The original plan called for a landing on Sunday, 04 July. However, imaging of the intended landing site from orbit revealed that a landing there would be a high risk venture. With this revelation, Viking project scientists went into high stress mode to locate a suitable alternate landing location.

On Tuesday, 20 August 1976, the Viking I lander separated from the Viking orbiter at 0851 UTC in preparation for the deorbit burn.

The Viking I atmospheric deceleration sequence began at roughly 1,000,000 feet above the Martian surface. An ablating aeroshell both slowed and protected the vehicle from aerodynamic heating down to 19,000 feet. At this point, a 52.5-foot diameter parachute was deployed to provide further slowing. At 4,000 feet, the aeroshell and parachute were jettisoned and the craft’s retro-rockets were fired

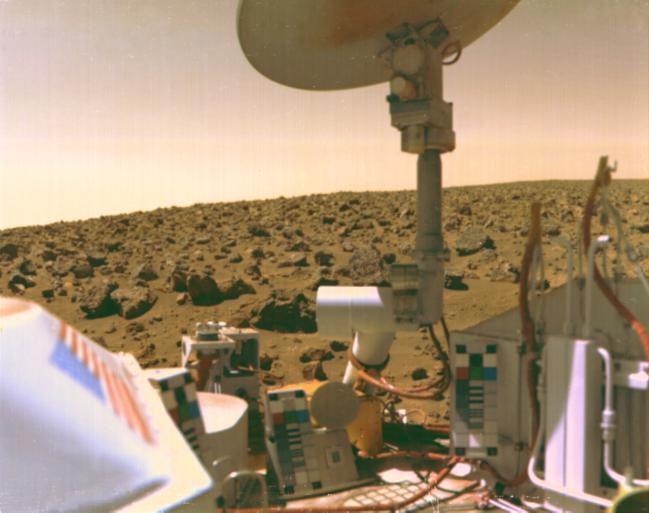

The Viking I lander touched-down at Chryse Planitia (“Golden Plain” in the Greek) at 1153 UTC having completed the first successful Martian entry, descent, and landing (EDL) mission. The Viking I landing mass was on the order of 1,320 lbs. (Point of clarification: the photo above was taken by Viking II which landed on Mars at Utopia Planitia (“Nowhere Plain”) on Friday, 03 September 1976.)

Viking I went on to perform a variety of first-ever scientific investigations on Mars. Key instrumentation included several cameras, a surface sampler arm, a meterology boom, a seismometer, and a variety of other sensors. In its search for signs of life, Viking I was also configured with an internal biology compartment and gas chromatograph mass spectrometer.

The Viking I lander was designed to function for a minimum of 90 days on the surface of Mars. In reality, it continued to function and provide useful science for over 6 years (contact lost 13 November of 1982). While it rewrote the book in terms of Martian planetary science, Viking I did not in fact discover defintive signs of life on Mars.