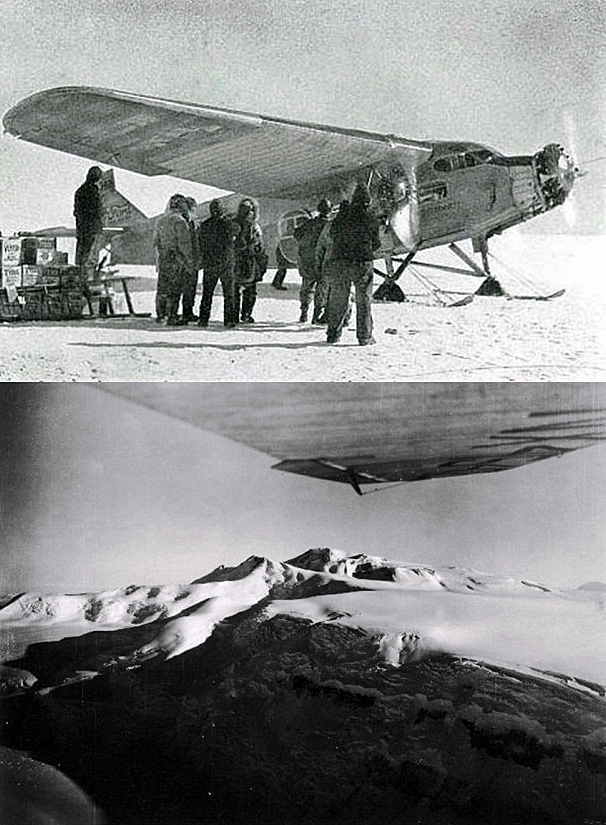

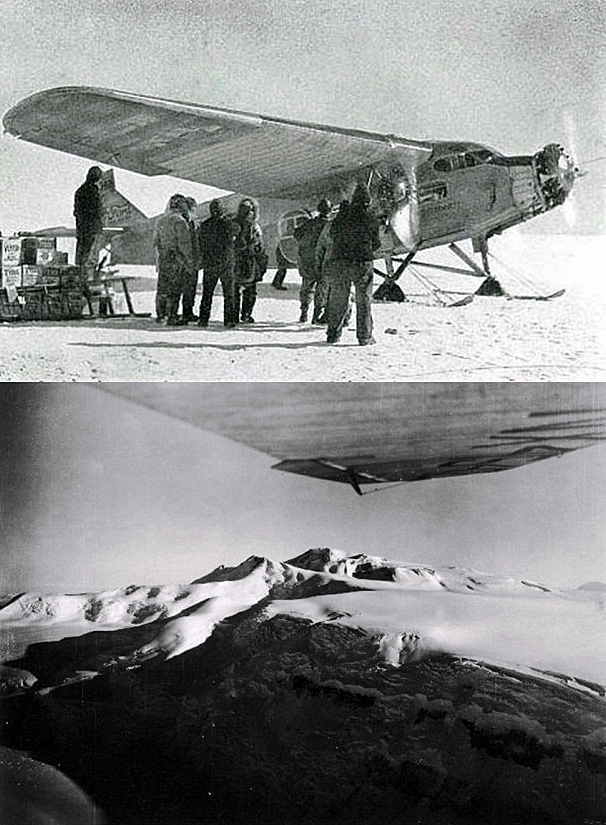

Eighty-seven years ago this week, a four-man crew became the first Antarctic explorers to fly over the Earth’s South Pole. The aircraft used to make the historic flight was a Ford Trimotor.

While substantial exploration of the Artic and Antarctic by land and sea had occurred far earlier, exploration of these regions by air was in its infancy during the decade of the 1920′s. Of particular focus was the goal to fly over both the North and South Poles.

The historic first flight to the South Pole originated from Little America, an exploration base camp situated on Antartica’s Ross Ice Shelf. Distance to the South Pole was about 800 miles as the crow flies.

A Ford Trimotor aircraft, the Floyd Bennett (S/N NX4542), was selected for the epic polar air journey. The crew consisted of pilot Bernt Balchen, co-pilot Harold June, navigator Richard E. Byrd, and radio operator Ashley McKinley.

The fabled Trimotor was well-suited for the rigors of polar flight. The all-metal aircraft measured 50-feet in length and had a wing span of 76-feet. Empty weight was roughly 6,500 pounds. Power was provided by a single 520-HP Wright Cylone and a pair of 200-HP Wright Whirlwind radial engines.

Following departure from Little America at 02:39 UTC, the Floyd Bennett headed for the South Pole. Navigation was via sun compass due to the proximity of the South Magnetic Pole.

Myriad glaciers, massifs, plateaus, and crevasses marked the stark, rugged landscape unfolding under the Floyd Bennett’s flight path. The most imposing of these geological features were the Queen Maud Mountains that towered more than 11,000 feet above sea level.

Pilot Balchen struggled to get his aircraft over the high mountain pass that runs between Mounts Fridtjof and Fisher. The crew jettisoned empty fuel cans and hundreds of pounds of precious food to lighten the load. The Floyd Bennett cleared the terrain by about 600 feet.

Just after 1200 UTC (local midnight) on Friday, 29 November 1929, the Floyd Bennett and her crew flew over the Earth’s South Pole. After briefly loitering around the Pole, the aircraft headed back to Little America at 1225 UTC.

According to plan, Balchen landed the airplane to take on 200 gallons of fuel that had been pre-positioned at the base of the Liv Glacier. The Floyd Bennett took-off again and landed back at Little America around 21:10 UTC. Total mission time was nearly 19 hours.

United States Navy Commander Richard E. Byrd now had flown over both poles. He would go on to successfully explore the Antarctic for many more years. For his part in the South Pole overflight, Byrd was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral.

Today, the aircraft that made the first flight over the South Pole in November 1929 is displayed in the Heroes of the Sky exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Fifty-five years ago this week, a United States Navy YF4H-1 Phantom II set a world absolute speed record of 1,606.342 mph. Piloting the aircraft for this record flight was United States Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Robert B. Robinson.

The McDonnell Douglas YF4H-1 Phantom II was first flown in May 1958. The aircraft measured 58 feet length with a wing span of 38 feet. Gross take-off weight was 44,000 pounds. A pair of General Electric J79-GE-8 turbojets produced a total of 34,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner.

The YF4H-1 was the first in a long line of Phantom II variants that would eventually see a production run of 5,195 aircraft. Second only to the nearly 10,000 production units of the multi-variant North American F-86 Sabre.

Since 1961 marked the 50th anniversary of Naval Aviation, the US Navy planned to celebrate by establishing a series of speed records. The aircraft of choice was their super-powered Phantom II. Operation SAGEBURNER was the low altitude speed program (i.e., 125 feet off the deck) while Operation SKYBURNER was the high altitude speed component.

On Wednesday, 22 November 1961, the second YF4H-1 (S/N 142260) took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California in an attempt to surpass the existing world absolute speed record. A United States Air Force F-106 Delta Dart, piloted by Major Joseph W. Rogers, held the existing record of 1,525.96 mph which was set on Tuesday, 15 December 1959.

Robinson had to fly a precisely-timed and positioned flight profile to extract maximum performance from his YF4H-1. FAI rules required the aircraft to enter the Edwards speed course in level flight and to make two runs. The final speed mark would be the average of the two runs.

The Phantom II was a big airplane and had to carry a lot of fuel. In addition to a full internal fuel load, the aircraft carried a 600-gallon centerline tank and a pair of 370-gallon wing tanks. Following take-off to the east, climb-out was made to the south toward El Centro, California. Arriving in the area, Robinson made a sweeping left-hand turn over the Salton Sea and accelerated the aircraft north back towards Edwards.

As the aircraft gained speed, Robinson dropped the empty centerline fuel tank over the Chocolate Mountains gunnery range. Then, arriving over the Bristol Dry Lake range, he punched-off the empty wing tanks. The aircraft was now lighter and aerodynamically cleaner.

Robinson approached the Edwards speed course from the east in full afterburner. The Phantom II exited the 20-mile course quickly. Following his first pass, Robinson came out of afterburner, made a Mach 0.9 turn to the south, cruised 105 miles out and then made the turn back to Edwards for the second speed pass.

His aircraft lighter now and not having to concern himself with the logistics of dropping empty fuel tanks, Robinson was clocked at over 1,700 mph on his second time through the Edwards speed course. The two-run average was 1,606.342 mph; a new world absolute speed record.

The F-4 Phantom II would go on to a legendary combat career in both the United States Navy and United States Air Force. Among many distinctions, the McDonnel Douglas F-4 Phantom II is the only aircraft to have seen service with both the USAF Thunderbirds (1969-1973) and the US Navy Blue Angels (1969-1974) flight demonstration squadrons.

For setting the world absolute speed record in 1961, Operation SKYBURNER pilot Bob Robinson was presented with the Distinguished Flying Cross by the then-Secretary of the Navy, John B. Connally.

Twelve years ago today, the NASA X-43A scramjet-powered flight research vehicle reached a record speed of over 6,600 mph (Mach 9.68). In doing so, the X-43A eclipsed its own record speed of Mach 6.83 (4,600 mph) and became the fastest airbreathing aircraft of all time.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X. The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The third and final flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 21:08 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 22:34:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership. Following a 5 second free fall, rocket motor ignition occurred and the HXLV initiated a pull-up to start its climb and acceleration to the test window. It took the HXLV 75 seconds to reach a speed of slightly over Mach 10.

Following rocket motor burnout and a brief coast period, the HXRV (X-43A) successfully separated from the Pegasus booster at 109,440 feet and Mach 9.74. The HXRV scramjet was operative by Mach 9.68. Supersonic combustion and thrust production were successfully achieved. Total engine-on duration was approximately 11 seconds.

As the X-43A decelerated along its post-burn descent flight path, the aircraft performed a series of data gathering flight maneuvers. A vast quantity of high-quality aerodynamic and flight control system data were acquired for Mach numbers ranging from hypersonic to transonic. Finally, the X-43A impacted the Pacific Ocean at a point about 850 nautical miles due west of its launch location. Total flight time was approximately 15 minutes.

The HYPER-X Program was now history. Supersonic combustion and thrust production of an airframe-integrated scramjet had indeed been achieved for the first time in flight; a goal that dated back to before the X-15 Program. Along the way, the X-43A established a speed record for airbreathing aircraft and earned several Guinness World Records for its efforts.

As a footnote to the X-43A story, the HYPER-X Flight 3 mission would also be the last for NASA’s fabled B-52B mothership. The aircraft that launched many of the historic X-15, M2-F2, M2-F3, X- 24A, X-24B and HL-10 flight research missions, and all three HYPER-X flights, would take to the air no more. In tribute, B-52B (S/N 52-0008) now occupies a place of honor at a point near the North Gate of Edwards Air Force Base.

Fifty-five years ago today, the USAF/NASA/North American X-15 became the first manned aircraft to exceed Mach 6. United States Air Force test pilot Major Robert M. White was at the controls of the legendary hypersonic flight research aircraft.

The North American X-15 was the first manned hypersonic aircraft. It was designed, engineered, constructed and first flown in the 1950’s. As originally conceived, the X-15 was designed to reach 4,000 mph (Mach 6) and 250,000 feet. Before its flight test career was over, the type would meet and exceed both performance goals.

North American built a trio of X-15 airframes; Ship No. 1 (S/N 56-6670), Ship No. 2 (56-6671) and Ship No. 3 (56-6672). The X-15 measured 50 feet in length, had a wing span of 22 feet and a GTOW of 33,000 lbs. Ship No. 2 would later be modified to the X-15A-2 enhanced performance configuration. The X-15A-2 had a length of 52.5 feet and a GTOW of around 56,000 lbs.

The Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine powered the X-15. The small, but mighty XLR-99 generated 57,000 pounds of sea level thrust at full-throttle. It weighed only 910 pounds. The XLR-99 used anhydrous ammonia and LOX as propellants. Burn time varied between 83 seconds for the stock X-15 and about 150 seconds for the X-15A-2.

The X-15 was carried to drop conditions (typically Mach 0.8 at 42,000 feet) by a B-52 mothership. A pair of aircraft were used for this purpose; a B-52A (S/N 52-003) and a B-52B (S/N 52-008). Once dropped from the mothership, the X-15 pilot lit the XLR-99 to accelerate the aircraft. The X-15A-2 also carried a pair of drop tanks which provided propellants for a longer burn time than was possible with the stock X-15 flight.

The X-15 employed both aerodynamic and reaction flight controls. The latter were required to maintain vehicle attitude in space-equivalent flight. The X-15 pilot wore a full-pressure suit in consequence of the aircraft’s extreme altitude capability. The typical X-15 drop-to-landing flight duration was on the order of 10 minutes. All X-15 landings were performed deadstick.

On Thursday, 09 November 1961, USAF Major Robert M. White would fly his 11th X-15 mission. The X-15 and White had already become respectively the first aircraft and pilot to hit Mach 4 and Mach 5. On this particular day, White would be at the controls of X-15 Ship No. 2. The planned maximum Mach number for the mission was Mach 6.

At 17:57:17 UTC of the aforementioned day, X-15 Ship No. 2 was launched from the B-52B mothership commanded by USAF Captain Jack Allavie. Bob White lit the XLR-99 and pulled into a steep climb. Mid-way through the climb, White pushed-over and ultimately leveled-off at 101,600 feet. XLR-99 burnout occurred 83 seconds after ignition. At this point, White was traveling at 4,093 mph or Mach 6.04.

On this record flight, the X-15 was exposed to the most severe aerodynamic heating environment it had experienced to date. Decelerating through Mach 2.7, the right window pane on the X-15’s canopy shattered due to thermal stress. The glass pane remained intact, but White could not see out of it. Fortunately, he could see out of the left pane and made a successful deadstick landing on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards AFB.

For his Mach 6+ flight, Bob White was a recipient of both the 1961 Collier Trophy and the Iven C. Kincheloe Award. The year before, White had received the Harmon Trophy for his X-15 flight test work. He would go on to fly the X-15 to a still-standing FAI altitude record of 314,750 feet in July of 1962. For this accomplishment, White was awarded USAF Astronaut Wings.

Bob White flew the X-15 a total of sixteen (16) times. He was one (1) of only twelve (12) men to fly the aircraft. White left X-15 Program and Edwards AFB in 1963. He went on to serve his country in numerous capacities as a member of the Air Force including flying 70 combat missions in Viet Nam. He returned to Edwards AFB as AFFTC Commander in August of 1970.

Major General Robert M. White retired from the United States Air Force in 1981. During his period of military service, he received numerous decorations and awards including the Air Force Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star with three oak leaf clusters, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters, Bronze Star Medal, and Air Medal with 16 oak leaf clusters.

Bob White was a true American hero. He was one of those heroes who neither sought nor received much notoreity for his accomplishments. He served his country and the aviation profession well. Bob White’s final flight occurred on Wednesday, 17 March 2010. He was 85 years of age.

Fifty years ago this month, NASA’s pioneering spaceflight program, Project Gemini, was brought to a successful conclusion with the 4-day flight of Gemini XII. Remarkably, the mission was the tenth Gemini flight in 20 months.

Boosted to Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle, Gemini XII Command Pilot James A. Lovell, Jr. and Pilot Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 20:46:33 UTC on Friday, 11 November 1966. The flight was Lovell’s second trip into space and Aldrin’s first.

Like almost every Gemini mission before it, Gemini XII was not a glitch-free spaceflight. For instance, when the spacecraft’s rendezvous radar began acting oddly, the crew had to resort to sextant and chart to complete the last 65 nautical miles of the rendezvous with their Agena Target Vehicle. But, overcoming this and other obstacles served to provide the experience and instill the confidence needed to meet the truly daunting challenge that lay ahead; landing on the Moon.

Unquestionably, Gemini XII’s single most important contribution to the United States manned space effort was validating the notion that a well-trained astronaut could indeed do useful work in an Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) environment. The exhausting and even dangerous EVA experiences of Gene Cernan on Gemini IX and Dick Gordon on Gemini XI brought into sharp focus the challenge of performing even seemingly simple work assignments outside the Gemini spacecraft.

Buzz Aldrin performed a trio of EVA’s on Gemini XII. Two of these involved standing in his seat with the hatch open. The third involved a tethered EVA or space walk. On the latter, Aldrin successfully moved about the exterior of the Gemini-Agena combination without exhausting himself. He also used a special-purpose torque wrench to perform a number of important work tasks. Central to Aldrin’s success was the use of foot restraints and auxiliary tethers to anchor his body while floating in a weightless state.

Where others had struggled and not been able to accomplish mission EVA goals, Buzz Aldrin came off conqueror. One of the chief reasons for his success was effective pre-flight training. A pivotal aspect of this training was to practice EVA tasks underwater as a unique means of simulating the effects of weightlessness. This approach was found to be so useful that it has been used ever since to train American EVA astronauts.

Lovell and Aldrin did many more things during their highly-compressed 4-day spaceflight in November of 1966. Multiple dockings with the Agena, Gemini spacecraft maneuvering, tethered stationkeeping exercises, fourteen scientific experiments, and photographing a total eclipse occupied their time aloft.

On Tuesday, 15 November 1966, on their 59th orbit, a tired, but triumphant Gemini XII crew returned to Earth. The associated reentry flight profile was automated; that is, totally controlled by computer. Yet another first and vital accomplishment for Project Gemini. Splashdown was in the West Atlantic at 19:21:04 UTC.

While Gemini would fly no more, both Lovell and Aldrin certainly would. In fact, both men would play prominent roles in several historic flights to the Moon. Jim Lovell flew on Apollo 8 in December 1968 and Apollo 13 in April 1970. And of course, Buzz Aldrin would walk on the Moon at Mare Tranquilitatis in July 1969 as the Lunar Module Pilot for Apollo 11.