Forty-nine years ago this month, a USAF F-106A Delta Dart (S/N 58-0787) out of Malmstrom AFB, Montana made a wheels-up landing in a farmer’s field despite the fact that there was no pilot onboard. The pilot, Lieutenant Gary Foust, had ejected earlier when he was unable to recover the aircraft from a flat spin. This incident became known in popular culture as “The Cornfield Bomber”.

On Monday, 02 February 1970, a trio of pilots from the 71st Fighter Interceptor Squadron (FIS) took-off from Malmstrom AFB, Montana for the purpose of practicing air combat maneuvers. A fourth pilot had intended to be part of this group but was forced to abort the mission when his aircraft’s drag parachute strangely deployed on the ramp.

The pilots who took to the air that day were Major Thomas Curtis, Major James Lowe, and Faust. Each man was at the controls of a Convair F-106A Delta Dart; aka “The Ultimate Interceptor”. The three-ship formation departed Malmstrom for an area roughly 90 miles north of the base designated for the flying of air combat maneuvers and engagements.

The practice session began with a two-on-one head-on engagement. Approaching the other two aircraft at Mach 1.90 in full afterburner, Captain Curtis pulled his aircraft into the vertical. His intent was to induce the other pilots to follow him upstairs. They did so. In passing through 38,000 feet, he executed a vertical rolling scissors maneuver. However, Curtis had superior energy at the pull-up point. Thus, neither Lowe nor Foust could gain a tactical advantage in the fight. When Curtis executed a high-g rudder reversal, Foust attempted to stay with him. That’s when things deteriorated rapidly for Foust.

Foust flew his F-106A into an accelerated stall around 35,000 feet as he attempted to maintain position with Curtis. That is, his aircraft exceeded the stall angle-of-attack while simultaneously losing speed due to the motion-retarding effects of gravity and drag due to lift. The F-106A fell off into a series of post-stall gyrations followed by entry into a flat spin. The flat spin is a high angle-of-attack, deep stall condition from whence recovery was typically not possible in a Delta Dart.

Notwithstanding the futility of the task, Foust diligently applied anti-spin procedures in textbook fashion. However, the aircraft continued to fall in a flat spin. In desperation, Foust deployed his drag chute hoping that it would act as an anti-spin device. Unfortunately, the chute became totally useless for that purpose when it wrapped itself around the vertical tail of his falling steed. Running out of altitude and time, Foust had no other recourse but to abandon his airplane. He did so somewhere around 12,000 feet.

Foust was rocketed out of his Delta Dart and got a good chute. He landed in the Bear Paw Mountains, and fortunately was brought to safety by local citizens on snowmobiles. However, to the utter amazement of Foust, Curtis, and Lowe, the abandoned delta-winged aircraft snapped out of its flat spin and began to glide. Apparently, the equal and opposite reaction of the aircraft to the force produced by the rocket-powered ejection seat forced the nose of the airplane below the stall angle-of-attack. Thus, the wing began to produce lift again. Further, as part of his anti-spin procedures, Foust had configured the controls of the Delta Dart in take-off trim and brought the throttle to idle.

The net state of affairs now was that the F-106A became a pretty good glider. Gliding at about 175 knots, it ultimately made a wheels-up landing in a farmer’s snow-covered field near Big Sandy, Montana. The landing was aided by ground effect which enhanced the lift on the airplane as the vehicle neared the ground. Incredibly, the wings remained level throughout the landing slide-out. Further, late in the landing, the F-106A magically turned 20 degrees from its touchdown azimuth and avoided running into a pile of rockets directly in its path. In doing so, the airplane slipped through an opening in a fence around the farmer’s property and came to a stop.

When authorities approached the Delta Dart, they found that its canopy was gone, its ejection seat was gone, and so was its pilot. A look into the cockpit revealed that the radar scope was still sweeping for targets. And, although in idle, the still running turbojet produced a bit of thrust. Thus, periodically, the vehicle would lurch forward when the restraining snow around the it melted. Almost two hours later, the turbojet finally stopped running when the aircraft fuel supply ran out.

Remarkably, the pilotless Delta Dart sustained little damage despite the wheels-up landing. The aircraft was later trucked out of the area and sent to McClellan AFB in California for repairs. It ultimately was returned to service with the 71st FIS. Later, it entered the inventory of the 49th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Grifffiss AFB, New York. Fittingly, a measure of closure was accorded (then) Major Gary Foust when he flew this same aircraft again in 1979. Today, USAF F-106A Delta Dart, S/N 58-0787 sits on display for posterity at the USAF National Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

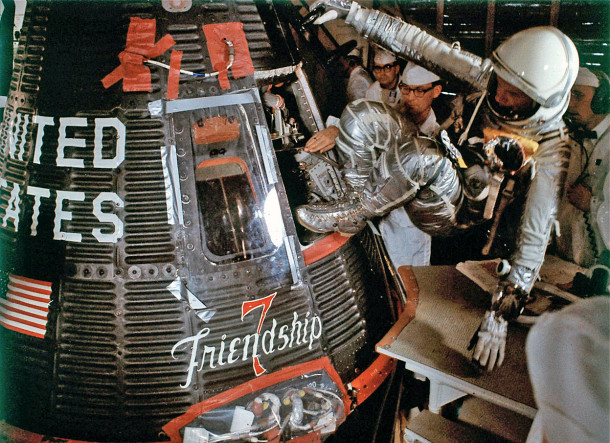

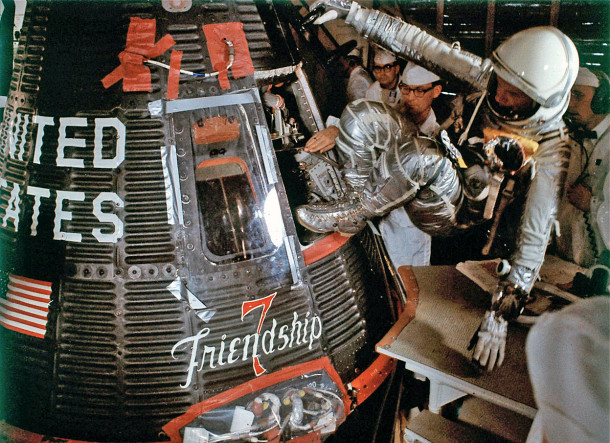

Fifty-seven years ago today, Project Mercury Astronaut John Herschel Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn’s spacecraft name and mission call sign was Friendship 7.

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 14 at 14:47:39 UTC on Tuesday, 20 February 1962. It was the first time that the Atlas LV-3B booster was used for a manned spaceflight.

Three-hundred and twenty seconds after lift-off, Friendship 7 achieved an elliptical orbit measuring 143 nm (apogee) by 86 nm (perigee). Orbital inclination and period were 32.5 degrees and 88.5 minutes, respectively.

The most compelling moments in the United States’ first manned orbital mission centered around a sensor indication that Glenn’s heat shield and landing bag had become loose at the beginning of his second orbit. If true, Glenn would be incinerated during entry.

Concern for Glenn’s welfare persisted for the remainder of the flight and a decision was made to retain his retro package following completion of the retro-fire sequence. It was hoped that the 3 flimsy straps holding the retro package would also hold the heat shield in place.

During Glenn’s return to the atmosphere, both the spent retro package and its restraining straps melted in the searing heat of re-entry. Glenn saw chunks of flaming debris passing by his spacecraft window. At one point he radioed, “That’s a real fireball outside”.

Happily, the spacecraft’s heat shield held during entry and the landing bag deployed nominally. There had never really been a problem. The sensor indication was found to be false.

Friendship 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at a point 432 nm east of Cape Canaveral at 19:43:02 UTC. John Glenn had orbited the Earth 3 times during a mission which lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds. In short order, spacecraft and astronaut were successfully recovered aboard the USS Noa.

John Glenn became a national hero in the aftermath of his 3-orbit mission aboard Friendship 7. It seemed that just about every newspaper page in the days following his flight carried some sort of story about his historic feat. Indeed, it is difficult for those not around back in 1962 to fully comprehend the immensity of Glenn’s flight in terms of what it meant to the United States.

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. passed away on 08 December 2016 at the age of 95. His trusty Friendship 7 spacecraft is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Sixty-four years ago this month, North American test pilot George F. Smith became the first man to survive a low altitude, high dynamic pressure ejection from an aircraft in supersonic flight. Smith ejected from his F-100A Super Sabre at 777 MPH (Mach 1.05) as the crippled aircraft passed through 6,500 feet in a near-vertical dive.

On the morning of Saturday, 26 February 1955, North American Aviation (NAA) test pilot George F. Smith stopped by the company’s plant at Los Angeles International Airport to submit some test reports. Returning to his car, he was abruptly hailed by the company dispatcher. A brand-new F-100A Super Sabre needed to be test flown prior to its delivery to the Air Force. Would Mr. Smith mind doing the honors?

Replying in the affirmative, Smith quickly donned a company flight suit over his street clothes, got the rest of his flight gear and pre-flighted the F-100A Super Sabre (S/N 53-1659). After strapping into the big jet, Smith went through the normal sequence of aircraft pre-launch flight control and system checks. While the control column did seem a bit stiff in pitch, Smith nonetheless decided that his aerial steed was ready for flight.

Smith executed a full afterburner take-off to the west. The fleet Super Sabre eagerly took to the air. Accelerating and climbing, the aircraft was almost supersonic as it passed through 35,000 feet. Peaking out around 37,000 feet, Smith sensed a heaviness in the flight control column. Something wasn’t quite right. The jet was decidedly nose heavy. Smith countered by pulling aft stick.

The Super Sabre did not respond at all to Smith’s control inputs. Instead, it continued an un-commanded dive. Shallow at first, the dive steepened even as the 215-lb pilot pulled back on the stick with all of his might. But all to no avail. The jet’s hydraulic system had failed. As the stricken aircraft now accelerated toward the ground, Smith rightly concluded that this was going to be a short ride.

George Smith knew that he had only one alternative now; Eject. However, he also knew that the chances were quite small that he would survive what was quickly shaping-up to be a quasi-supersonic ejection. Suddenly, over the radio, Smith heard another Super Sabre pilot flying in his vicinity frantically yell: “Bail out, George!” So exhorted, the test pilot complied.

Smith jettisoned his canopy. The roar from the airstream around him was unlike anything he had ever heard. Almost paralyzed with fear, Smith reflexively hunkered-down in the cockpit. The exact wrong thing to do. His head needed to be positioned up against the seat’s headrest and his feet placed within retraining stirrups prior to ejection. But there was no time for any of that now. Smith pulled the ejection seat trigger.

George Smith’s last recollection of his nightmare ride was that the Mach Meter read 1.05; 777 mph at the ejection altitude of 6,500 feet above the Pacific Ocean. These flight conditions corresponded to a dynamic pressure of 1,240 pounds per square foot. As he was fired out of the cockpit and into the harsh air stream, Smith’s body was subjected to an astounding drag force of around 8,000 lbs producing on the order of 40-g’s of deceleration.

Mercifully, Smith did not recall what came next. The ferocious wind blast stripped him of his helmet, oxygen mask, footwear, flight gloves, wrist watch and even his ring. Blood was forced into his head which became grotesquely swollen and his facial features unrecognizable. His eyelids fluttered and his eyes were tortuously mauled by the aerodynamic and inertial load of his ejection. Smith’s internal organs, most especially his liver, were severely damaged. His body was horribly bruised and beaten as it flailed end-over-over end uncontrollably.

Smith and his seat parted company as programmed followed by automatic deployment of his parachute. The opening forces were so high that a third of the parachute material was ripped away. Thankfully, the remaining portion held together and the unconscious Smith landed about 75 yards away from a fishing vessel positioned about a half-mile form shore. Providentially, the boat’s skipper was a former Navy rescue expert. Within a minute of hitting the water, Smith was rescued and brought onboard.

George Smith was hovering near death when he arrived at the hospital. In severe shock and with only a faint pulse, doctors quickly went to work. Smith awoke on his sixth day of hospitalization. He could hear, but he couldn’t see. His eyes had sustained multiple subconjunctival hemorrhages and the prevailing thought at the time was that he would never see again.

Happily, George Smith did recover almost fully from his supersonic ejection experience. He spent seven (7) months in the hospital and endured several operations. During that time, Smith’s weight dropped to 150 lbs. He was left with a permanently damaged liver to the extent that he could no longer drink alcohol. As for Smith’s vision, it returned to normal. However, his eyes were ever after somewhat glare-sensitive and slow to adapt to darkness.

Not only did George Smith return to good health, he also got back in the cockpit. First, he was cleared to fly low and slow prop-driven aircraft. Ultimately, he got back into jets, including the F-100A Super Sabre. Much was learned about how to markedly improve high speed ejection survivability in the aftermath of Smith’s supersonic nightmare. He in essence paid the price so that others would fare better in such circumstances as he endured.

It is possible that George Smith was not the first pilot to eject supersonically. USN LCdr Authur Ray Hawkins survived ejection from his stricken Grumman F9F-6 Cougar in 1953. Aircraft speed at ejection was never definitively determined, but was estimated to be between 688 (Mach 0.99) and 782 mph (Mach 1.16). In any event, the dynamic pressure and therefore the airloads associated with Hawkins ejection were less than half that of Smith’s punch-out.

George Smith was thirty-one (31) at the time of his F-100A mishap. He lived a happy and productive thirty-nine (39) more years after its occurrence. Smith passed from this earthly scene in 1994.

Forty-five years ago this month, the USAF/General Dynamics YF-16 Lightweight Fighter (LWF) took to the air on its official first flight with General Dynamics test pilot Phil Oestricher at the controls. The YF-16 would go on to win the high stakes Air Combat Fighter competition following a head-to-head fly-off against Northrop’s very capable YF-17 Cobra.

The YF-16 was General Dynamics entry into the USAF Lightweight Fighter Program of the 1970’s. Its basic design was based on USAF Colonel John Boyd’s Energy Maneuverability (EM) Theory which posited that an aircraft with superior energy capability would defeat an aircraft of lesser energy capability in air combat. To achieve such, EM Theory dictated a small, lightweight aircraft having a high thrust-to-weight ratio, which permitted maneuvering at minimum energy loss. The YF-16 was an embodiment of this requirement.

The official first flight of the YF-16 (S/N 72-1567) took place on Saturday, 02 February 1974 at Edwards Air Force Base, California. General Dynamics test pilot Phil Oestricher (pronounced Ol-Striker) did the piloting honors. The nimble aircraft performed very well and was a delight to fly. Oestricher landed uneventfully following a brief test hop that saw the YF-16 reach 400 mph and 30,000 feet.

Interestingly, the real first flight of the YF-16 inadvertently occurred on Sunday, 20 January 1974 during what was supposed to be a high-speed taxi test. As the aircraft accelerated rapidly down the runway, Oestricher raised the nose slightly and applied aileron control to check lateral response. To the pilot’s surprise, the aircraft entered a roll oscillation with amplitudes so high that the left wing and right stabilator alternately struck the surface of the runway.

As Oestricher desperately fought to maintain control of his wild steed, the situation became increasingly dire as the YF-16 began to veer to the left. Realizing that going into the weeds at high speed was a prescription for disaster, the test pilot quickly elected to jam the throttle forward and attempt to get the YF-16 into the air. The outcome of this decision was not immediately obvious as Oestricher continued to struggle for control while waiting for his airspeed to increase to the point that there was lift sufficient for flight.

When the YF-16 finally became airborne, it departed the runway on a heading roughly 45 degrees to the left of the centerline. Oestricher somehow maintained control of the aircraft during the rugged lift-off and early climbout phases of flight. The pilot then successfully executed a go-around, entry into final approach, and landing back on the departure runway. A tough way to earn a day’s pay by any standard!

History records that the YF-16 went on to win the Air Combat Fighter (ACF) competition with Northrop’s YF-17 Cobra. The production aircraft became known as the F-16 Fighting Falcon, of which more than 4,500 aircraft, in numerous variants, were built between 1976 and 2010. The now-famous aircraft has clearly fulfilled the measure of its creation as evidenced by its presence in the military inventory of more than 25 countries worldwide. Significantly, America’s Ambassadors in Blue, The United States Air Force Thunderbirds, have flown the F-16 in air demonstrations since 1983.

While its initial foray into the air did not necessarily lend confidence that such would be the case, the YF-16 did survive its flight test career. Aviation aficionados may view the actual aircraft at the Virginia Air and Space Center located in Hampton, Virginia.