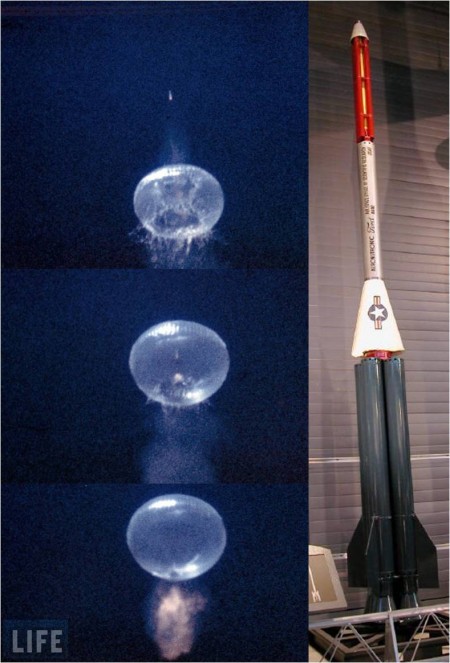

Fifty-five years ago this month, the final test shot in the Operation Farside test series took place near Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The final stage of the 4-stage research rocket reached a top speed close to 18,000 mph.

Operation Farside was a USAF Office of Scientific Research project intended to probe the space environment to altitudes as high as 3,400 nm. The approach taken for doing so involved launching a 4-stage rocket from a balloon floating at an altitude of 100,000 feet. Firing the rocket from this height significantly reduced the vehicle’s aerodynamic drag and allowed it to fly much higher than if launch had occurred at sea level.

The 4-stage Farside rocket measured 24 feet in length and had a maximum diameter of 1.5 feet. Firing weight of the Aeronutronics-developed vehicle was 1,900 lbs. Stages 1 and 2 utilized fins for providing static stability while Stage 3 and 4 were spin-stabilized. Each of these stages employed solid rocket propulsion.

The Farside payload weighed a mere 4 lbs. Its job was to measure the cosmic ray, electromagnetic radiation, space gas, and space dust environments and transmit the data back to Earth.

The Farside rocket was carried to launch altitude by a 3.75-million cubic foot, helium-filled, polyethelene film balloon. The vehicle was cradled within an aluminum lattice-work launch tower suspended directly below the balloon. Upon ignition of the first stage rocket motor, the Farside rocket fired right through the middle of its carrier balloon.

There were six (6) shots in the Operation Fireside test series. The first vehicle was launched on Wednesday, 25 September 1957. However, the mission failed when the carrier balloon malfunctioned. The remaining five (5) test rounds were fired in October of 1957. Unfortunately, the next three (3) flights suffered ignition failures in one or more stages.

Operation Farside finally enjoyed some success with Test Shot 5, flown on Sunday, 20 October 1957. While all of the stages functioned as planned, the probe’s telemetry system failed to transmit any scientific data back to the ground. The inoperative transmitter resulted in degraded tracking, with the result that the apogee altitude of the round was never known with accuracy.

The sixth and final Operation Farside test shot occurred on Tuesday, 22 October 1957. Ironically, the results of this flight were essentially the same as Test Shot 5. All of the stages fired, but telemetry system failure once again resulted in loss of mission environmental and performance data. At this point, Operation Farside was fresh out of balloons and rocket vehicles. And with that, the program was officially over.

The United States Air Force had hoped to follow Operation Farside with a more ambitious program to fly a 5-stage, rocket-powered vehicle within shouting distance of the moon. A review of the historical record reveals that such a program was never in fact pursued.

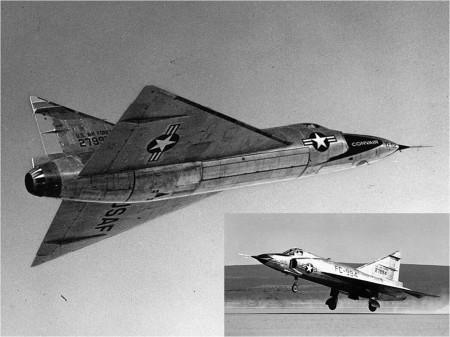

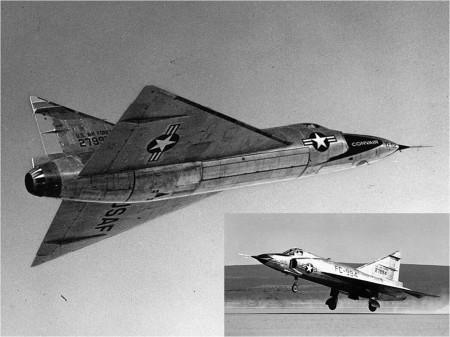

Fifty-nine years ago this week, the USAF/Convair YF-102 Delta Dagger all-weather interceptor prototype flew for the first time in the skies over Edwards Air Force Base. Convair test pilot Richard Lowe “Dick” Johnson was at the controls of the delta-winged, turbojet-powered aircraft.

The F-102 Delta Dagger was the third Century Series aircraft to enter production. Known as the Deuce, the aircraft was designed as an all-weather, supersonic interceptor. Its mission was protect the continental United States from attack by Soviet strategic bombers. The type’s primary armament consisted of a bevy of six (6) internally-carried Falcon air-to-air missiles.

The Deuce was the product of the 1954 Interceptor Project begun by USAF in the late 1940’s. A direct descendant of Convair’s pioneering XF-92A Dart, the Delta Dagger was that company’s second delta wing-configured, turbojet-powered aircraft. Convair’s clear preference for the delta wing planform was destined to become a company trademark throughout the 1950’s. Arguably the highest expression of this design feature came in the form of the Convair F-106 Delta Dart and B-58A Hustler supersonic aircraft.

First flight of the first YF-102 protype (S/N 52-7994) took place on Saturday, 24 October 1953. The aircraft was powered by a Pratt and Whitney J57 turbojet rated at 14,500 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner. Unfortunately, this flight test and several that closely followed shocked Convair aircraft designers with the revelation that the Deuce could not fly supersonically. The aircraft simply generated too much transonic wave drag.

Faced with the gravity of the situation, Convair quickly went to work to markedly improve the performance of its troubled delta wing steed. Thanks largely to a fortuitously-timed discovery by NACA aerodynamicist Richard Whitcomb, the Delta Dagger’s performance potential would eventually be realized. Whitcomb’s aerodynamic breakthrough was referred to as the Transonic Area Rule.

Briefly, Richard Whitcomb discovered that the transonic wave drag of an aircraft could be reduced by ensuring a smooth variation of the aircraft’s nose-to-tail cross-sectional area development. Elimination of abrupt changes in this distribution corresponded to a reduction in the strength of localized shock waves.

Combined with an uprated version of the Deuce’s Pratt and Whitney J57 powerplant, application of Whitcomb’s Transonic Area Rule resulted in a sleeker and faster aircraft known as the YF-102A. While it took over a year to effect the necessary changes, the YF-102A easily achieved supersonic flight on Tuesday, 21 December 1954.

The Convair F-102 Delta Dagger went on to a fine operational career lasting 20 years with the United States Air Force and United States Air National Guard. The last of 1,000 airframes was retired from active piloted service in 1976.

White Eagle Aerospace salutes Felix Baumgartner and the entire Red Bull Stratos Team for yesterday’s record breaking jump from the edge of space. Indeed, Sunday, 14 October 2012 will long be remembered, not only for one of the most remarkable achievements in aerospace history, but for a most uncommon display of human courage.

As of this writing, the prelimary accomplishments of this historic feat read as follows:

Highest Manned Balloon Flight: 128,097 feet above sea level

Longest Freefall Distance: 119,846 feet

Highest Velocity Achieved During a Freefall: 834 mph

First Supersonic Freefall: Mach 1.24

Baumgartner’s plunge to Earth lasted 9 minutes and 3 seconds with a freefall duration of 4 minutes and 20 seconds.

Baumgartner overcame many obstacles in his quest to jump from an altitude higher than any man before him. Key among these obstacles were the many physical dangers inherent in extreme altitude flight as well as a highly personal battle with claustrophobia when sealed within a full pressure suit.

It took 52 years for the freefall marks of the previous record holder (Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr.) to be eclipsed. And in a coming day, Baumgartner’s incredible achievements will be surpassed as well. But on this day, we pay tribute to an intrepid and courageous soul. Well done Mr. Baumgartner!

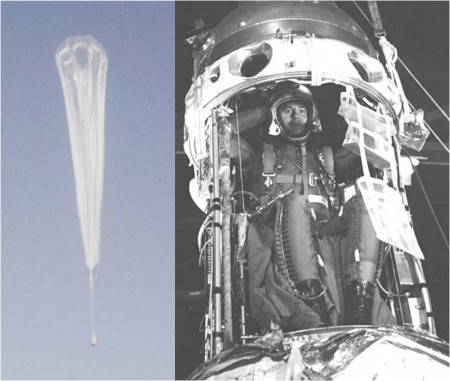

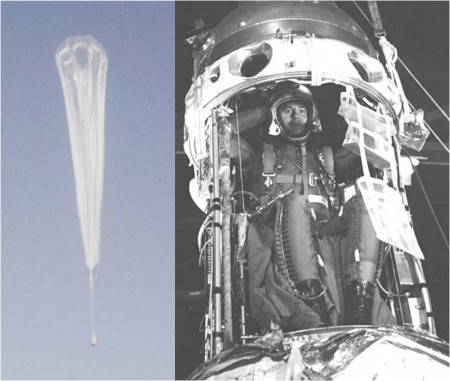

Fifty-four years ago today, USAF Lt Clifton M. McClure successfully completed the Manhigh III aeromedical mission in which he reached an altitude of 98,000 feet. During the descent phase of his nearly-12 hours aloft, McClure’s core body temperature reached an astounding 108.6 F.

Project Manhigh was a United States Air Force biomedical research program that investigated the human factors of spaceflight by taking men into a near-space environment. Preparations for the trio of Manhigh flights began in 1955. The experience and data gleaned from Manhigh were instrumental to the success of the nation’s early manned spaceflight effort.

The Manhigh target altitude was approximately 100,000 feet above sea level. A helium-filled polyethylene balloon, just 0.0015-inches thick and inflatable to a maximum volume of over 3-million cubic feet, carried the Manhigh gondola into the stratosphere. At float altitude, this balloon expanded to a diameter of about 200 feet.

The Manhigh gondola was a hemispherically-capped cylinder that measured 3-feet in diameter and 8-feet in length (increased to 9-feet for Manhiogh III). It was attached to the transporting balloon via a 40-foot diameter recovery parachute. Although compact, the gondola was amply provisioned with the necessities of flight including life support, power and communication systems. It also included expendable ballast for use in controlling the altitude of the Manhigh balloon.

The Manhigh test pilot wore a T-1 partial pressure suit during the Manhigh mission. This would protect him in the event that the gondola cabin lost pressure at extreme altitude. The pilot was hooked-up to a variety of sensors which transmitted his biomedical information to the ground throughout the flight. This allowed medicos on the ground to keep a constant tab on the pilot’s physical status.

The first two Manhigh missions were flown in 1957. USAF Captain Joseph W. Kittinger reached an altitude of 95,200 ft during the 6-hour, 32-minute Manhigh I mission of Sunday, 02 June 1957. USAF Major David G. Simons flew the 32-hour, 10-minute mission of Manhigh II on Sunday-Monday, 18-19 August 1957. Simons soared to a Project Manhigh record altitude of 101,516 feet.

Manhigh III was launched from Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico on Wednesday, 08 October 1958. USAF Lt Clifton M. McClure was the pilot and research specimen for the mission. The huge Manhigh balloon lifted-off with McClure and his dimunitive capsule at 1151 UTC. The trip upstairs took roughly 3 hours and resulted in a float altitude of 98,000 feet.

Interestingly, a launch attempt the day before had been aborted when a wind gust tore the thin mylar balloon while the ground crew was preparing it for launch. The next day, as McClure awaited launch within the Manhigh III capsule, his chest-mounted emergency parachute inexplicably ejected and plopped into the pilot’s lap. Incredibly, McClure repacked the parachute (not once, but twice) and managed to avoid another mission abort.

Clifton McClure uneventfully went through his Manhigh flight plan until ground control noticed that the pilot was evidencing signs of degraded performance. The pilot’s pulse rate and core body temperature were elevated as well. It turned out that McClure had not ingested any water fover the previous 11 hours! However, after being instructed to hydrate himself, McClure could only get a few drops of water at a time due to a problem with his drinking tube. Within 10 minutes, he had fixed the problem and could then drink freely.

A significant reason that McClure’s body temperature began to rise was due to ineffective cooling of the Manhigh III capsule. On previous Manhigh missions, the capsule dome was repacked with dry ice just prior to launch. However, on Manhigh III, a decision was made to dispense with the repacking procedure. The result was that the heat generated by the Manhigh pilot’s body and capsule systems ultimately exceeded the cooling capacity of the environmental control system.

Around 1900 UTC, the decision was made to end the mission and bring McClure down. However, the trip back to Earth was excruciatingly slow. By 2100 UTC, the capsule was still at 87,000 feet and McClure’s core body temperature had risen to 104.1 F. It was all McClure could to just to remain conscious as his body temperature continued to soar. Finally, at 2342 UTC, the Manhigh III capsule settled onto the desert floor. In spite of the fact that McClure’s internal body temperature registered a phenomenal 108.6 F, the pilot egressed the Manhigh capsule under his own power.

During his Manhigh III experience, Clifton McClure exceeded by 137 percent what was then thought to be the limit for human heat tolerance. He received the USAF Distinguished Flying Cross in recognition of his superlative performance. Following his military career, McClure plied the engineer’s trade until retirement. Clifton M. McClure passed away in January of 2000 at the age of 68.

Twenty-seven years ago this week, the Space Shuttle Atlantis was launched on its maiden spaceflight. Known as Mission STS-51J, the flight made Atlantis the fourth member of the Space Shuttle Orbiter fleet to reach Earth orbit.

Mission STS-51J marked the twenty-first orbital flight of the Space Shuttle Program. The primary objective of Atlantis’ first mission was to deploy a Department of Defense (DoD) satellite payload to geostationary orbit. The all-military crew included Commander Karol J. Bobko, Pilot Ronald J. Grabe, Mission Specialists David C. Hilmers and Robert L. Stewart, and Payload Specialist William A. Pailes.

Although classified at the time, the STS-51J payload is suspected to have consisted of a pair of Defense Satellite Communications System (DSCS) satellites. The function of these Lockheed-developed spacecraft was to provide a secure communications capability in support of vital military installations situated across the globe.

Atlantis was launched from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Thursday, 03 October 1985. Lift-off time occurred at 15:15:30 UTC. The new orbiter was successfully inserted into a near-circular orbit having a mean altitude of 219-nm. Orbital inclination and period were 28.5-deg and 94.2 minutes, respectively.

Following deployment from Atlantis’ payload bay, a single Boeing Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) successfully propelled the pair of DSCS satellites into geostationary orbit. With each satellite weighing 5,760 lbs, the total DSCS-IUS stack tipped the scales at 44,020 lbs.

Atlantis orbited the globe 64 times before returning to Earth on Monday, 07 October 1985. The Orbiter touched-down on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California at 17:00:08 UTC. Total mission time was 97 hours, 44 minutes and 38 seconds. From lift-off to landing, Atlantis and her crew flew a total distance of 1,462,203 nm.

History records that Atlantis flew 33 (24.4%) of the 135 missions flown over the life of the Space Shuttle Program. During an “operational” flight career spanning 1985 to 2011, Atlantis and her crews contributed immensely to American spaceflight. Key among many accomplishments were helping to build the International Space Station (ISS), refurbishing the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), launching of the Magellan Probe to Venus, and launching the Galileo Probe to Jupiter.

Like her other stable mates, Atlantis no longer graces the heavens with her presence. She had the honor (?) of flying the final Space Shuttle mission (STS-135) in July of 2011. Now eternally rooted to the ground, Atlantis resides on public display at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.