Sixty-one years ago today, the United States successfully orbited the country’s first space satellite. Known as Explorer I, the artificial moon went on to discover the Van Allen Radiation Belts, the extensive system of charged particles trapped in the magnetosphere that surrounds the Earth.

The Explorer I satellite was designed and fabricated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) under the direction of Dr. William J. Pickering. The satellite’s instrumentation unit measured 37.25 inches in length, 6.5 inches in diameter, and had a mass of only 18.3 lbs. With its burned-out fourth stage solid rocket motor attached, the total on-orbit mass of the pencil-like satellite was 30.8 lbs.

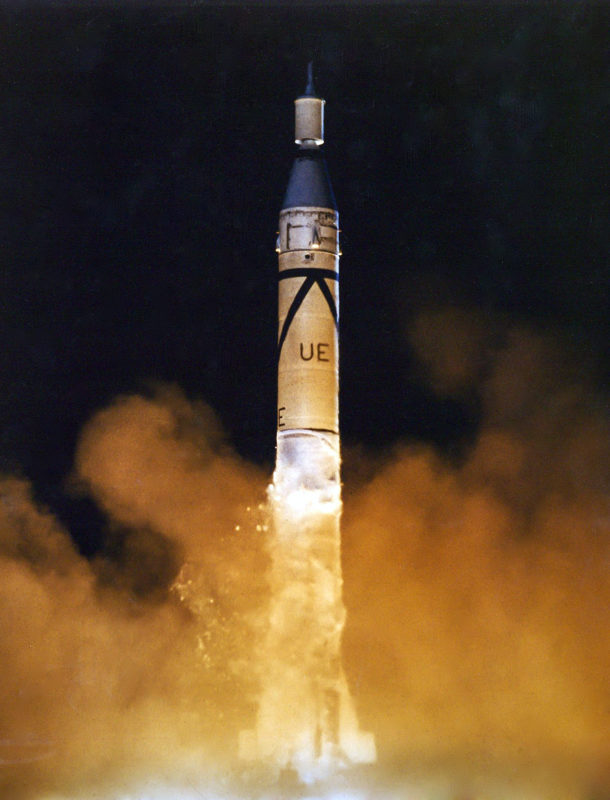

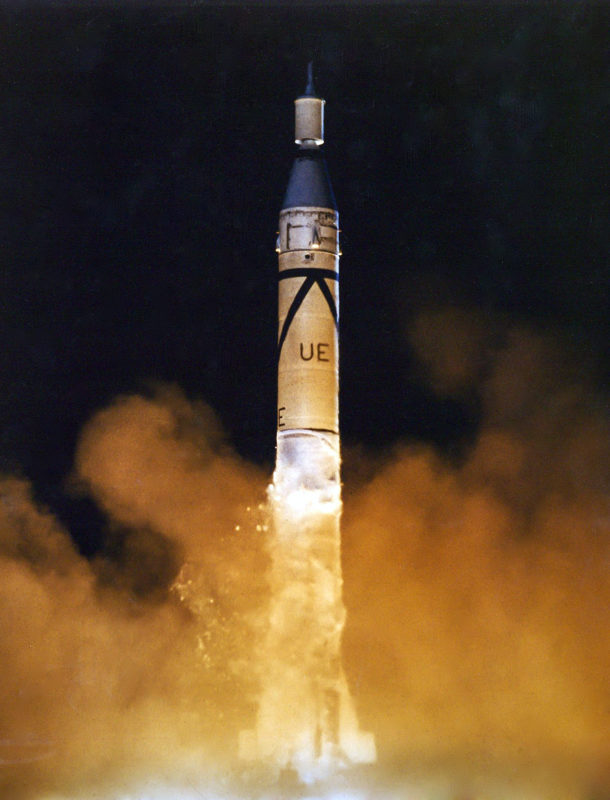

Explorer I was launched aboard a Jupiter-C (aka Juno I) launch vehicle from LC-26 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Friday, 31 January 1958. Lift-off at occurred at 22:48 EST (0348 UTC). With all four stages performing as planned, Explorer I was inserted into a highly elliptical orbit having an apogee of 1,385 nm and a perigee of 196 nm.

Arguably the most historic achievement of the Explorer I mission was the discovery of a system of charged particles or plasma within the magnetosphere of the Earth. These belts extend from an altitude of roughly 540 to 32,400 nm above mean sea level. Most of the plasma that forms these belts originates from the solar wind and cosmic rays. The radiation levels within the Van Allen Radiation Belts (named in honor of the University of Iowa’s Dr. James A. Van Allen) are such that spacecraft electronics and astronaut crews must be shielded from the adverse effects thereof.

Explorer I operational life was limited by on-board battery life and lasted a mere 111 days. However, it soldiered-on in orbit until reentering the Earth’s atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on Tuesday, 31 March 1970. During the 147 months it spent in space, Explorer I orbited the Earth more than 58,000 times. Data obtained and transmitted by the satellite contributed markedly to mankind’s understanding of the Earth’s space environment.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of Explorer I was that it was the first satellite orbited by the United States. Unknown to most today, this accomplishment was absolutely vital to America’s security, and indeed that of the free world, at the time. The Soviet Union had been first in space with the orbiting of the much larger Sputnik I and II satellites in late 1957. However, Explorer I showed that America also had the capability to orbit a satellite. History records that this capability would quickly grow and ultimately lead to the country’s preeminence in space.

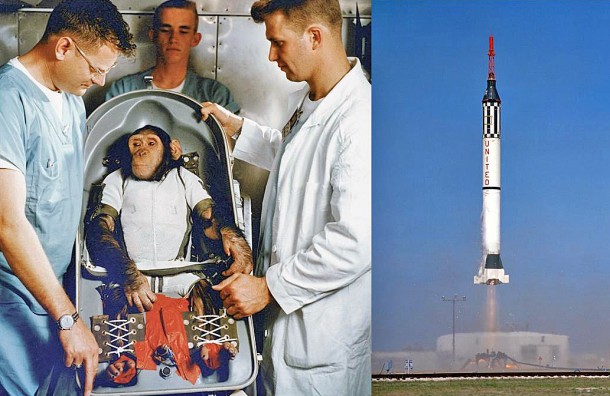

Fifty-eight years ago this month, NASA successfully conducted a critical flight test of the space agency’s Mercury-Redstone launch vehicle which helped clear the way for the United States’ first manned suborbital spaceflight. Riding the Mercury spacecraft into space and back was a diminutive 44-month old male chimpanzee by the name of HAM.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. Simply stated, Mercury helped us learn how to fly astronauts in space and return them safely to earth. A total of six (6) manned missions were flown between May of 1961 and May of 1963. The first two (2) flights were suborbital shots while the final four (4) flights were full orbital missions. All were successful.

The Mercury spacecraft weighed about 3,000 lbs, measured 9.5-ft in length and had a base diameter of 6.5-ft. Though diminutive, the vehicle contained all the systems required for manned spaceflight. Primary systems included guidance, navigation and control, environmental control, communications, launch abort, retro package, heatshield, and recovery.

Mercury spacecraft launch vehicles included the Redstone and Atlas missiles. Both were originally developed as weapon systems and therefore had to be man-rated for the Mercury application. Redstone, an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM), was the booster for Mercury suborbital flights. Atlas, an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), was used for orbital missions.

Early Mercury-Redstone (MR) flight tests did not go particularly well. The subject missions, MR-1 and MR-1A, were engineering test and development flight tests flown with the intent of man-rating both the converted launch vehicle and new manned spacecraft.

MR-1 hardly flew at all in that its rocket motor shut down just after lift-off. After soaring to the lofty altitude of 4-inches, the vehicle miraculously settled back on the launch pad without toppling over and detonating its full load of propellants. MR-1A flew, but owing to higher-than-predicted acceleration, went much higher and farther than planned. Nonetheless, MR flight testing continued in earnest.

The objectives of MR-2 were to verify (1) that the fixes made to correct MR-1 and MR-1A deficiencies indeed worked and (2) proper operation of a bevy of untested systems as well. These systems included environmental control, attitude stabilization, retro-propulsion, voice communications, closed-loop abort sensing and landing shock attenuation. Moreover, MR-2 would carry a live biological payload (LBP).

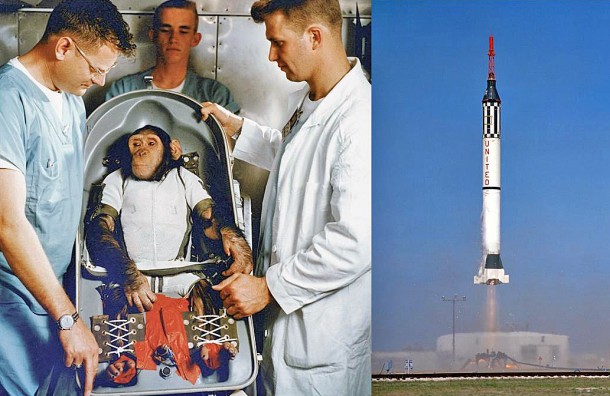

A 44-month old male chimpanzee was selected as the LBP. He was named HAM in honor of the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center where the primate trained. HAM was taught to pull several levers in response to external stimuli. He received a banana pellet as a reward for responding properly and a mild electric shock as punishment for incorrect responses. HAM wore a light-weight flight suit and was enclosed within a special biopack during spaceflight.

On Tuesday, 31 January 1961, MR-2 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-5 at 16:55 UTC. Within one minute of flight, it became obvious to Mission Control that the Redstone was again over-accelerating. Thus, HAM was going to see higher-than-planned loads at burnout and during reentry. Additionally, his trajectory would take him higher and farther downrange than planned. Nevertheless, HAM kept working at his lever-pulling tasks.

The Redstone burnout velocity was 5,867 mph rather than the expected 4,400 mph. This resulted in an apogee of 137 nm (100 nm planned) and a range of 367 nm (252 nm predicted). HAM endured 14.7 g’s during entry; well above the 12 g’s planned. Total flight duration was 16.5 minutes; several minutes longer than planned.

Chillingly, HAM’s Mercury spacecraft experienced a precipitous drop in cabin pressure from 5.5 psig to 1 psig just after burnout. High flight vibrations had caused the air inlet snorkel valve to open and dump cabin pressure. HAM was both unaware of and unaffected by this anomaly since he was busy pulling levers within the safety of his biopack.

HAM’s Mercury spacecraft splashed-down at 17:12 UTC about 52 nm from the nearest recovery ship. Within 30 minutes, a P2V search aircraft had spotted HAM’s spacecraft (now spaceboat) floating in an upright position. However, by the time rescue helicopters arrived, the Mercury spacecraft was found floating on its side and taking on sea water.

Apparently, a combination of impact damage to the spacecraft’s pressure bulkhead and the open air inlet snorkel valve resulted in HAM’s spacecraft taking on roughly 800 lbs of sea water. Further, heavy ocean wave action had really hammered HAM and the Mercury spacecraft. The latter having had its beryllium heatshield torn away and lost in the process.

Fortunately, one of the Navy rescue helicopters was able to retrieve the waterlogged spacecraft and deposit it safely on the deck of the USS Donner. In short order, HAM was extracted from the Mercury spacecraft. Despite the high stress of the day’s spaceflight and recovery, HAM looked pretty good. For his efforts, HAM received an apple and an orange-half.

While the MR-2 was judged to be a success, one more flight would eventually be flown to verify that the Redstone’s over-acceleration problem was fixed. That flight, MR-BD (Mercury-Redstone Booster Development) took place on Friday, 24 March 1961. Forty-two (42) days later USN Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became America’s first astronaut.

MR-2 was HAM’s first and only spaceflight experience. He quietly lived the next 17 years as a resident of the National Zoo in Washington, DC. His last 2 years were spent living at a North Carolina zoo. On Monday, 19 January 1983, HAM passed away at the age of 26. HAM is interred at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in Alamogordo, NM.

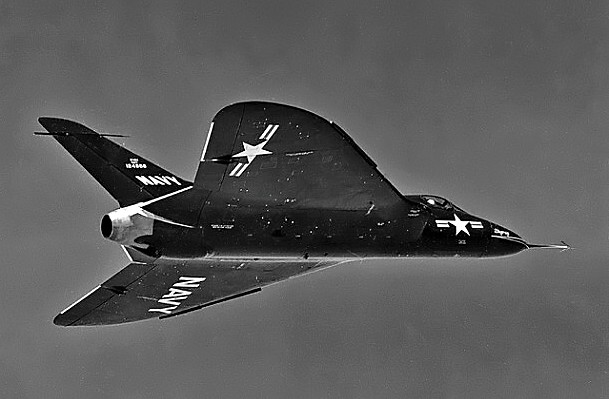

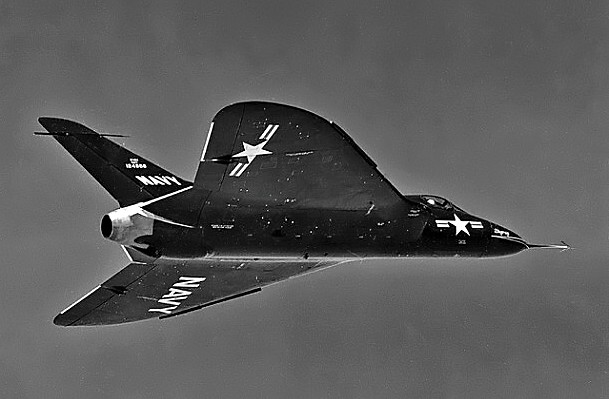

Sixty-six years ago this month, the USN/Douglas XF4D-1 Skyray fighter flew for the first time at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Douglas test pilot Robert O. Rahn was at the controls of the single-engine, carrier-based, supersonic-capable aircraft.

The Douglas XF4D-1 was the prototype version of the United States Navy’s F4D-1 Skyray. Designed to intercept adversary aircraft at 50,000 feet within 300 seconds of take-off, development of the Skyray began in the late 1940’s. As an aside, the Skyray nickname derived from the type’s large delta wing which gave it the appearance of a Manta ray.

The Skyray was originally designed to be powered by a Westinghouse XJ40-WE-6 turbojet capable of 7,000 lbs of sea level thrust. However, when significant developmental problems were encountered with that power plant, Douglas substituted an Allison J35-A-17 turbojet to support early flight testing of the XF4D-1. With a maximum sea level thrust of 5,000 lbs, the J35 rendered these early airframes significantly under-powered.

A pair of XF4D-1 Skyray airframes were built by Douglas. Ship No. 1 was assigned tail number BuAer 124586 while Ship No. 2 received the designation BuAer 124587.

On Tuesday, 23 January 1953, XF4D-1 Ship No. 1 (BuAer No 124586) departed Edwards Air Force Base on its first ride into the wild blue. Doing the piloting honors on this occasion was highly regarded Douglas test pilot Bob Rahn. The delta-winged beauty performed well on this maiden flight which concluded with Rahn making an uneventful landing back at Edwards.

Extensive flight testing of the Skyray, including carrier trials, continued through 1955. The Westinghouse XJ40-WE-8 appeared on the scene during this time. Rated at 11,600 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner, this power plant allowed the Skyray to establish several speed records in California during October of 1953. Specifically, a speed of 752.944 mph was registered within a 3-kilometer course over the Salton Sea followed by 100-kilometer closed course mark of 728.11 mph at Edwards AFB.

Unfortunately, the XJ40 would prove to be very temperamental and unreliable. Inflight engine fires, explosions, and component failures constantly plagued the Skyray program. Westinghouse never did solve these problems to the satisfaction of the Navy. As a result, the service eventually opted to power production aircraft with the Pratt and Whitney J57-P-8 turbojet (10,200 lbs of sea level thrust).

The Douglas F4D-1 Skyray went on to serve with the United States Navy and Marines from 1956 through 1964. A total of 420 aircraft were produced. While never used in anger, the Skyray was a solid performer and served well in its intended role as a point design interceptor.

The Skyray holds the distinction of being the last fighter produced by the Douglas Aircraft Company before this legendary aerospace giant merged with McDonnell Aircraft to form McDonnell Douglas.

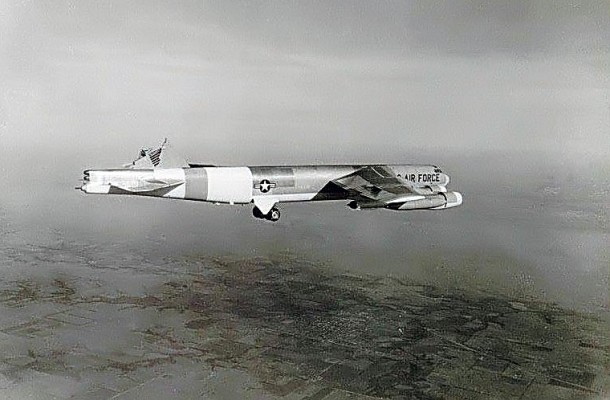

Fifty-five years ago today, a USAF/Boeing B-52H Stratofortress landed safely following structural failure of its vertical tail during an encounter with unusually severe clear air turbulence. The harrowing incident occurred as the aircraft was undergoing structural flight testing in the skies over East Spanish Peak, Colorado.

Turbulence is the unsteady, erratic motion of an atmospheric air mass. It is attributable to factors such as weather fronts, jet streams, thunder storms and mountain waves. Turbulence influences the motion of aircraft that are subjected to it. These effects range from slight, annoying disturbances to violent, uncontrollable motions which can structurally damage an aircraft.

Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) occurs in the absence of clouds. Its presence cannot be visually observed and is detectable only through the use of special sensing equipment. Hence, an aircraft can encounter CAT without warning. Interestingly, the majority of in-flight injuries to aircraft crew and passengers are due to CAT.

On Friday, 10 January 1964, USAF B-52H (S/N 61-023) took-off from Wichita, Kansas on a structural flight test mission. The all-Boeing air crew consisted of instructor pilot Charles Fisher, pilot Richard Curry, co-pilot Leo Coors, and navigator James Pittman. The aircraft was equipped with accelerometers and other sensors to record in-flight loads and stresses.

An 8-hour flight was scheduled on a route that from Wichita southwest to the Rocky Mountains and back. The mission called for 10-minutes runs of 280, 350 and 400 KCAS at 500-feet AGL using the low-level mode of the autopilot. The initial portion of the mission was nominal with only light turbulence encountered.

However, as the aircraft turned north near Wagon Mound, New Mexico and headed along a course parallel to the mountains, increasing turbulence and tail loads were encountered. The B-52H crew then elected to discontinue the low level portion of the flight. The aircraft was subsequently climbed to 14,300 feet AMSL preparatory to a run at 350 KCAS.

At approximately 345 KCAS, the Stratofortress and its crew experienced an extreme turbulence event that lasted roughly 9 seconds. In rapid sequence the aircraft pitched-up, yawed to the left, yawed back to the right and then rolled right. The flight crew desperately fought for control of their mighty behemoth. But the situation looked grim. The order was given to prepare to bailout.

Finally, the big bomber’s motion was arrested using 80% left wheel authority. However, rudder pedal displacement gave no response. Control inputs to the elevator produced very poor response as well. Directional stability was also greatly reduced. Nevertheless, the crew somehow kept the Stratofortress flying nose-first.

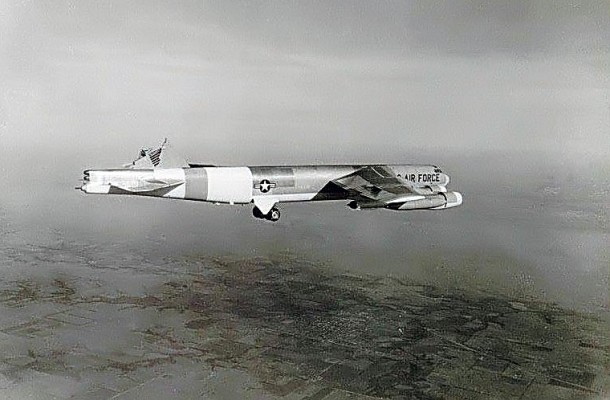

The B-52H crew informed Boeing Wichita of their plight. A team of Boeing engineering experts was quickly assembled to deal with the emergency. Meanwhile, a Boeing-bailed F-100C formed-up with the Stratofortress and announced to the crew that most of the aircraft’s vertical tail was missing! The stricken aircraft’s rear landing was then deployed to add back some directional stability.

With Boeing engineers on the ground working with the B-52H flight crew, additional measures were taken in an effort to get the Stratofortress safely back on the ground. These measures included a reduction in airspeed, controlling aircraft center-of-gravity via fuel transfer, judicious use of differential thrust, and selected application of speed brakes.

Due to high surface winds at Wichita, the B-52H was vectored to Eaker AFB in Blytheville, Arkansas. A USAF/Boeing KC-135 was dispatched to escort the still-flying B-52H to Eaker and to serve as an airborne control center as both aircraft proceeded to the base. Amazingly, after flying 6 hours sans a vertical tail, the Stratofortress and her crew landed safely.

Safe recovery of crew and aircraft brought additional benefits. There were lots of structural flight test data! It was found that at least one gust in the severe CAT encounter registered at nearly 100 mph. Not only were B-52 structural requirements revised as a result of this incident, but those of other existing and succeeding aircraft as well.

B-52H (61-023) was repaired and returned to the USAF inventory. It served long and well after its close brush with catastrophe in January 1964. The aircraft spent the latter part of its flying career as a member of the 2nd Bomb Wing at Barksdale AFB, Louisiana. The venerable bird was retired from active service in July of 2008.

Seventy years ago this week, the USAF/Bell XS-1 became the first aircraft of any type to achieve supersonic flight during a climb from a ground take-off. The daring feat took place at Muroc Air Force Base with USAF Captain Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager at the controls of the rocket-powered XS-1.

Rocket-powered X-aircraft such as the XS-1, X-1A, X-2 and X-15 were air-launched from a larger carrier aircraft. With the test aircraft as its payload, this “mothership” would take-off and climb to drop altitude using its own fuel load. This capability permitted the experimental aircraft to dedicate its entire propellant load to the flight research mission proper.

The USAF/Bell XS-1 was the first X-aircraft. It was carried to altitude by a USAF/Boeing B-29 mothership. XS-1 air-launch typically occurred at 220 mph and 22,000 feet. On Tuesday, 14 October 1947, the XS-1 first achieved supersonic flight. The XS-1 would ultimately fly as fast as Mach 1.45 and as high as 71,902 feet.

All but two (2) of the early X-aircraft were Air Force developments. The exceptions were products of the United States Navy flight research effort; the USN/Douglas D-558-I Skystreak and USN/Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket. The Skystreak was a turbojet-powered, straight-winged, transonic aircraft. The Skyrocket was supersonic-capable, swept-winged, and rocket-powered. Each aircraft was originally designed to be ground-launched.

In the best tradition of interservice rivalry, the Navy claimed that the D-558-I at the time was the only true supersonic airplane since it took to the air under its own power. Interestingly, the Skystreak was able fly beyond Mach 1 only in a steep dive. Nonetheless, the Air Force was indignant at the Navy’s insinuation that the XS-1 was somehow less of an X-aircraft because it was air-launched.

Motivated by the Navy’s affront to Air Force honor, the junior military service devised a scheme to ground-launch the XS-1 from Rogers Dry Lake at Muroc (now Edwards) Air Force Base. The aircraft would go supersonic in what was essentially a high performance take-off and climb. To boot, the feat was timed to occur just before the Navy was to fly its rocket-powered D-558-II Skyrocket. Justice would indeed be served!

XS-1 Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-062) was selected for the ground take-off mission. Captain Charles E. Yeager would pilot the sleek craft with Captain Jackie L. Ridley providing vital engineering support. Due to its somewhat fragile landing gear, the XS-1 propellant load was restricted to 50% of capacity. This provided approximately 100 seconds of rocket-powered flight.

On Wednesday, 05 January 1949, Yeager fired all four (4) barrels of his XLR-11 rocket motor. Behind 6,000 pounds of thrust, the XS-1 quickly accelerated along the smooth surface of the dry lake. After a take-off roll of only 1,500 feet and with the XS-1 at 200 mph, Yeager pulled back on the control yoke. The XS-1 virtually leapt into the desert air.

The aerodynamic loads were so high during gear retraction that the actuator rod broke and the wing flaps tore away. Unfazed, Yeager’s eager steed climbed rapidly. Eighty seconds after brake release, the XS-1 hit Mach 1.03 passing through 23,000 feet. Yeager then brought the XS-1 to a wings level flight attitude and shutdown his XLR-11 powerplant.

Following a brief glide back to the dry lake, Yeager executed a smooth dead-stick landing. Total flight time from lift-off to touchdown was on the order of 150 seconds. While a little worst for wear, the plucky XS-1 had performed like a champ and successfully accomplished something that it was really not designed to do.

Yeager was so excited during the take-off roll and high performance climb that he forgot to put his oxygen mask on! Potentially, that was a problem since the XS-1 cockpit was inerted with nitrogen. Fortunately, late in the climb, Yeager got his mask in place just before he went night-night for good.

Suffice it to say that the United States Navy was not particularly fond of the display of bravado and airmanship exhibited on that long-ago January day. The Air Force had emerged victorious in a classic contest of one-upmanship. Indeed, Air Force honor had been upheld. And, as was often the case in the formative years of the United States Air Force, it was a test pilot named Chuck Yeager who brought victory home to the blue suiters.