Eleven years ago this month, the NASA X-43A scramjet-powered flight research vehicle reached a record speed of over 4,600 mph (Mach 6.83). The test marked the first time in the annals of aviation that a flight-scale scramjet accelerated an aircraft in the hypersonic Mach number regime.

NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X in 1996. The fundamental goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed nearly 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The second flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 27 March 2004. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 20:40 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 21:59:58 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership. Following a 5 second free fall, rocket motor ignition occurred and the HXLV initiated a pull-up to start its climb and acceleration to the test window. It took the HXLV about 90 seconds to reach a speed of slightly over Mach 7.

Following HXLV rocket motor burnout and a brief coast period, the HXRV (X-43A) successfully separated from the Pegasus booster at 94,069feet and Mach 6.95. The HXRV scramjet engine was operative by Mach 6.83. Supersonic combustion and thrust production were successfully achieved. The total engine-on duration was approximately 11 seconds.

As the X-43A decelerated along its post-burn descent flight path, the aircraft performed a series of data gathering flight maneuvers. A vast quantity of high-quality aerodynamic and flight control system data were acquired for Mach numbers ranging from hypersonic to transonic. Finally, the X-43A impacted the Pacific Ocean at a point about 450 nautical miles due west of its launch location. Total flight time was approximately 15 minutes.

The HYPER-X Program made history that day in late March 2004. Supersonic combustion and thrust production of an airframe-integrated scramjet were achieved for the first time in flight; a goal that dated back to before the X-15 Program. Along the way, the X-43A established a speed record for airbreathing aircraft and earned a Guinness World Record for its efforts.

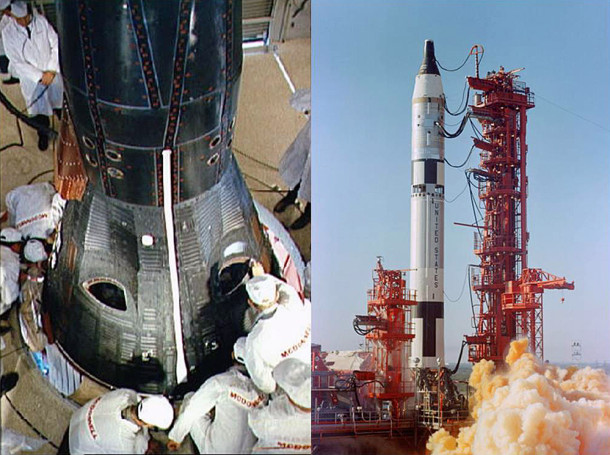

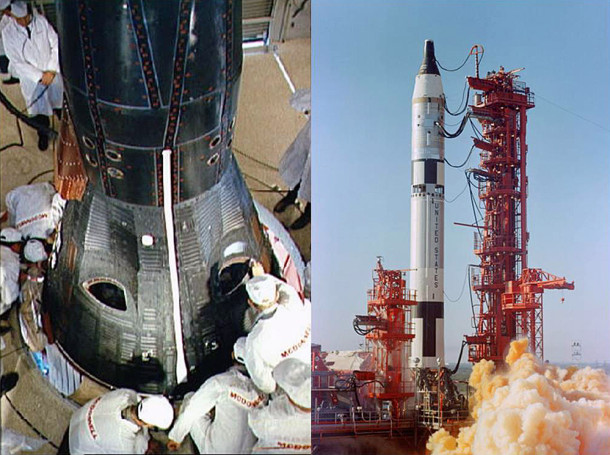

Fifty years ago this week, Gemini III was launched into Earth orbit with astronauts Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom and John W. Young onboard. The 3-orbit mission marked the first time that the United States flew a multi-man spacecraft.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight series. Project Apollo would ultimately land men on the Moon and return them safely to the Earth. In between these historic spaceflight efforts would be Project Gemini.

The purpose of Project Gemini was to develop and flight-prove a myriad of technologies required to get to the Moon. Those technologies included spacecraft power systems, rendezvous and docking, orbital maneuvering, long duration spaceflight and extravehicular activity.

The Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the deboost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbit attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

Gemini-Titan III (GT-3) lifted-off at 14:24 UTC from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Tuesday, 23 March 1965. The two-stage Titan II launch vehicle placed Gemini 3 into a 121 nautical mile x 87 nautical mile elliptical orbit.

Gemini 3’s primary objective was to put the maneuverable Gemini spacecraft through its paces. While in orbit, Grissom and Young fired thrusters to change the shape of their orbital flight path, shift their orbital plane, and dip down to a lower altitude. Gemini 3 was also the first time that a manned spacecraft used aerodynamic lift to change its entry flight path.

As spacecraft commander, Gus Grissom named his cosmic chariot The Molly Brown in reference to a then-popular Broadway show; “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”. Grissom chose the moniker in memory of his first spaceflight experience wherein his Liberty Bell 7 Mercury spacecraft sunk in almost 17,000 feet of water during post-splashdown operations.

At almost two (2) hours into the mission, pilot John Young presented Grissom with his favorite sandwich which had been smuggled onboard. Grissom and Young took a bite of the corned beef sandwich and put it away since loose crumbs could get into spacecraft electronics with catastrophic results. Not amused, NASA management reprimanded the crew after the mission.

Gemini 3 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 19:16:31 UTC following a 3 orbit mission. The spacecraft landed 45 nautical miles short of the intended splashdown point due to a misprediction of aerodynamic lift. Although hot and sea-sick, Commander Grissom refused to open the spacecraft hatches until the recovery ship USS Intrepid came on station.

Nine (9) additional Gemini space missions would follow the flight of Gemini 3. Indeed, the historical record shows that the Gemini Program would fly an average of every two (2) months by the time Gemini XII landed in December 1966. During that period, the United States would take the lead in the race to the Moon that it would never relinquish.

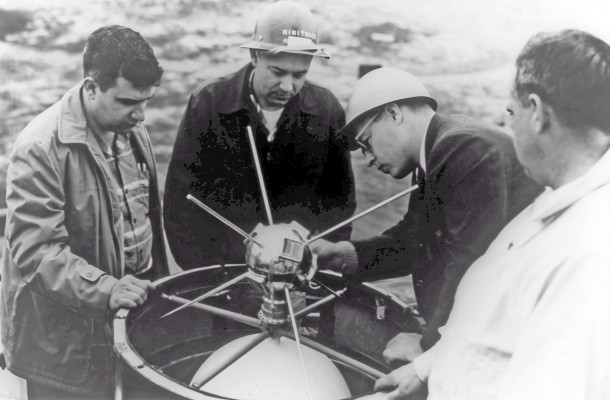

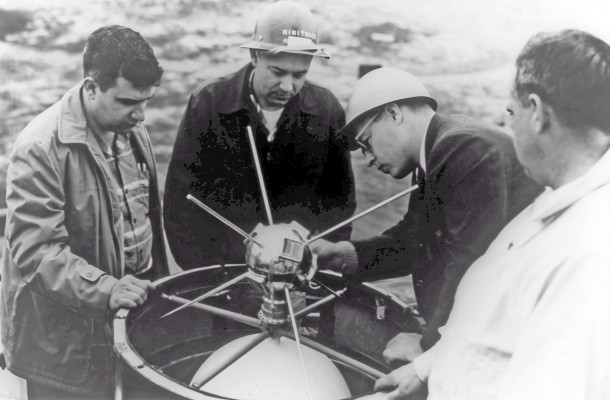

Fifty-seven years ago today, the United States Navy Vanguard Program registered its first success with the orbiting of the Vanguard 1 satellite. The diminutive orb was the fourth man-made object to be placed in Earth orbit.

The Vanguard Program was established in 1955 as part of the United States involvement in the upcoming International Geophysical Year (IGY). Spanning the period between 01 July 1957 and 31 December 1958, the IGY would serve to enhance the technical interchange between the east and west during the height of the Cold War.

The overriding goal of the Vanguard Program was to orbit the world’s first satellite sometime during the IGY. The satellite was to be tracked to verify that it achieved orbit and to quantify the associated orbital parameters. A scientific experiment was to be conducted using the orbiting asset as well.

Vanguard was managed by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). This gave the Vanguard Program a distinctly scientific (rather than military) look and feel. Something that the Eisenhower Administration definitely wanted to project given the level of Cold War tensions.

The key elements of Vanguard were the Vanguard launch vehicle and the Vanguard satellite. The Vanguard 3-stage launch vehicle, manufactured by the Martin Company, evolved from the Navy’s successful Viking sounding rocket. The Vanguard satellite was developed by the NRL.

On Friday, 04 October 1957, the Soviet Union orbited the world’s first satellite – Sputnik I. While the world was merely stunned, the United States was quite shocked by this achievement. A hue and cry went out across the land. How could this have happened? Will the Soviets now unleash nuclear weapons on us from space? And most hauntingly – where is our satellite?

In the midst of scrambling to deal with the Soviet’s space achievement, America would receive another blow to the national solar plexus on Sunday, 03 November 1957. That is the day that the Soviet Union orbited their second satellite – Sputnik II. And this one even had an occupant onboard; a mongrel dog name Laika.

The Vanguard Program was uncomfortably in the spotlight now. But it really wasn’t ready at that moment to be America’s response to the Soviets. After all, Vanguard was just a research program. While the launch vehicle was developing well enough, it certainly was not ready for prime time. The Vanguard satellite was a new creation and had never been used in space.

History records that the first American satellite launch attempt on Friday, 06 December 1957 went very badly. The launch vehicle lost thrust at the dizzying height of 4 feet above the pad, exploded when it settled back to Earth and then consumed itself in the resulting inferno. Amazingly, the Vanguard satellite survived and was found intact at the edge of the launch pad.

Faced with a quickly deteriorating situation, America desperately turned to the United States Army for help. Wernher von Braun and his team at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) responded by orbiting Explorer I on Friday, 31 January 1958. America was now in space!

The Vanguard Program regrouped and attempted to orbit a Vanguard satellite on Wednesday, 05 February 1958. Fifty-seven seconds into flight the launch vehicle exploded. Vanguard was now 0 for 2 in the satellite launching business. Undeterred, another attempt was scheduled for March.

Monday, 17 March 1958 was a good day for the Vanguard Program and the United States of America. At 12:51 UTC, Vanguard launch vehicle TV-4 departed LC-18A at Cape Canaveral, Florida and placed the Vanguard 1 satellite into a 2,466-mile x 406-mile elliptical orbit. On this Saint Patrick’s Day, Vanguard registered its first success and America had a second satellite orbiting the Earth.

Whereas the Soviet satellites weighed hundreds of pounds, Vanguard 1 was tiny. It was 6.4-inches in diameter and weighed only 3.25 pounds. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev mockingly referred to it as America’s “grapefruit satellite”. Small maybe, but mighty as well. Vanguard 1 went on to record many discoveries that helped write the book on spaceflight.

Khrushchev is gone and all of those big Sputniks were long ago incinerated in the fire of reentry. Interestingly, the “grapefruit satellite” is still in space and is the oldest satellite in Earth orbit. Vanguard 1 has completed roughly 200,000 Earth revolutions and traveled over 5.7 billion nautical miles since 1957. It is expected to stay in orbit for another 240 years. Not bad for a grapefruit.

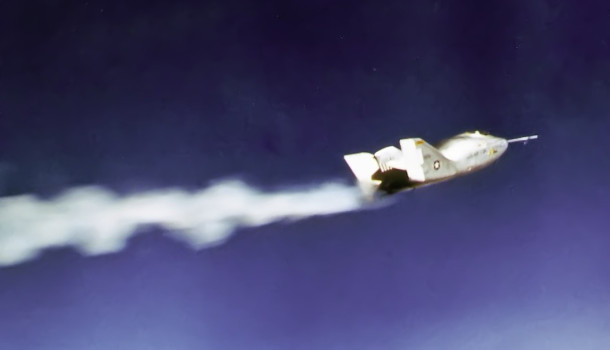

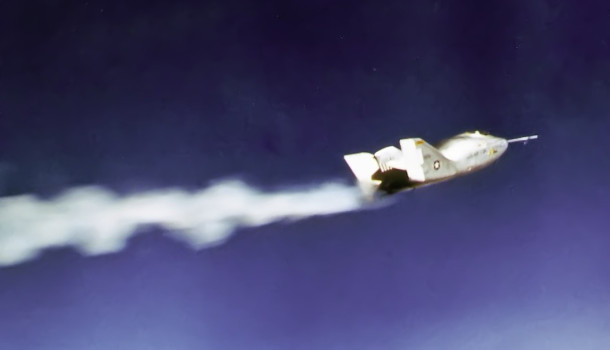

Forty-four years ago this month, the USAF/NASA X-24A lifting body was flown to a speed of 1,036 mph (Mach 1.6) by NASA Research Pilot John Manke. It was the highest speed ever attained by the rocket-powered lifting body.

A lifting body is an unconventional aircraft in that the vehicle generates lift without the benefit of a wing. Rather, the aircraft produces lift by the manner in which its fuselage is shaped.

In the early days of manned spaceflight, there were two schools of thought regarding the preferred mode of entry from orbital flight. One camp favored ballistic entry where the predominant flight force was aerodynamic drag. This was in contradistinction to lifting entry where both aerodynamic lift and drag forces were generated.

Ballistic entry is the more simple approach, but affords little control of the endoatmospheric flight path. This stems from the fact that the landing point for a ballistic entry is largely dictated by the entry vehicle’s velocity and flight path angle at entry interface.

While operationally more complicated, lifting entry provides a positive means for controlling the entry vehicle’s flight path and thus its landing point. At hypersonic speeds, even a small amount of lift markedly enhances entry vehicle downrange and crossrange capability.

Part of the complication of designing a lifting entry vehicle stems from the need to deal with high levels of heating during entry flight. The vehicle’s shape not only dictates its aerodynamic capabilities, but its aerodynamic heating characteristics as well. Thus, issues of flight path control and airframe survivability are interrelated.

The heyday of lifting body flight research spans the period from 1963 to 1975. For the record, the lifting bodies flown in that era include the following vehicles: M2-F1, M2-F2, M2-F3, HL-10, X-24A and X-24B. Each of these aircraft were piloted. All lifting body flight research was conducted at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The X-24A was developed by the Martin Company under contract to the United States Air Force. A single X-24A was produced. It measured 24.5 feet in length and had a gross weight of 11,450 pounds. Airframe empty weight was 6,300 pounds.

Though unconventional in shape, the X-24A incorporated full 3-axis flight controls. The aircraft was powered by the venerable XLR-11 rocket motor. Consisting of four rocket chambers, the XLR-11 was rated at 8,500 pounds of sea level thrust. Maximum burn time was on the order of 140 seconds. All landings of the squat little ship were conducted deadstick.

The X-24A displayed generally good handling characteristics, but had to be flown precisely. Angle-of-attack had to be maintained between about 4 and 12 degrees. Flight at lower and higher angles-of-attack encountered undesirable aerodynamic control and cross-coupling characteristics.

On Monday, 29 March 1971, X-24A (S/N 66-13551) fell away from the B-52B mothership in an effort to fly a maximum speed mission. NASA research pilot John Manke was at the controls. Manke accelerated the aircraft in a climb and reached a record speed of 1,036 mph (Mach 1.6). Interestingly, it was also John Manke who had previously flown the X-24A lifting body to its highest altitude of 71,407 feet on Tuesday, 27 October 1970.

The X-24A, like all of the lifting body aircraft, contributed significantly to the decision to land the Space Shuttle Orbiter deadstick. The lifting bodies, as well as X-aircraft such as the X-1, X-2, and X-15, proved conclusively that an unpowered aircraft could reliably (1) manage its energy state all the way to landing and (2) precisely control its touchdown point.

The X-24A flew a total of 28 flight research missions. Following its final flight, the X-24A was then converted to the radically different-appearing X-24B configuration which flew 36 times. Today, the X-24B is displayed in a place of honor in the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

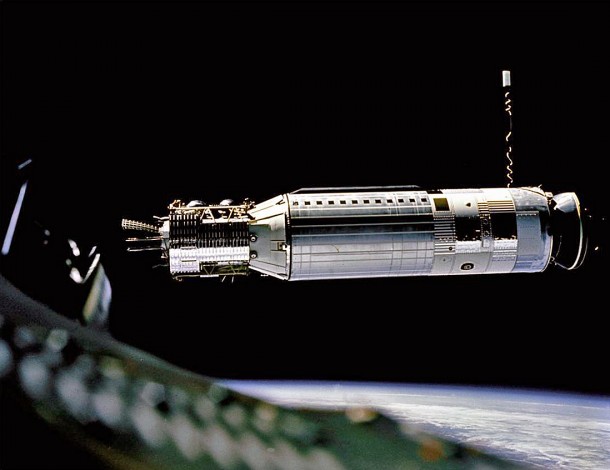

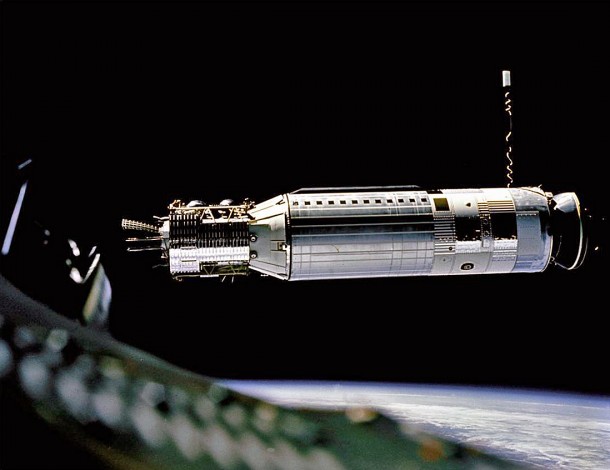

Forty-nine years ago this month, the crew of Gemini VIII successfully regained control of their tumbling spacecraft following failure of an attitude control thruster. The incident marked the first life-threatening on-orbit emergency and resulting mission abort in the history of Amercian manned spaceflight.

Gemini VIII was the sixth manned mission of the Gemini Program. The primary mission objective was to rendezvous and dock with an orbiting Agena Target Vehicle (ATV). Successful accomplishment of this objective was seen as a vital step in the Nation’s quest for landing men on the Moon.

The Gemini VIII crew consisted of Command Pilot Neil A. Armstrong and Pilot USAF Major David R. Scott. Both were space rookies. To them would go both the honor of achieving the first successful docking in orbit as well as the challenge of dealing with the first life and death space emergency involving an American spacecraft.

Gemini VIII lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 16:41:02 UTC on Wednesday, 16 March 1966. The crew’s job was to chase, rendezvous and then physically dock with an Agena that had been launched 101 minutes earlier. The Agena successfully achieved orbit and waited for Gemini VIII in a 161-nm circular Earth orbit.

It took just under six (6) hours for Armstrong and Scott to catch-up and rendezvous with the Agena. The crew then kept station with the target vehicle for a period of about 36 minutes. Having assured themselves that all was well with the Agena, the world’s first successful docking was achieved at a Gemini mission elasped time of 6 hours and 33 minutes.

Once the reality of the historic docking sank in, a delayed cheer erupted from the NASA and contractor team at Mission Control in Houston, Texas. Despite the complex orbital mechanics and delicate timing involved, Armstrong and Scott had actually made it look easy. Unfortunately, things were about to change with an alarming suddeness.

As the Gemini crew maneuvered the Gemini-Agena stack, their instruments indicated that they were in an uncommanded 30-degree roll. Using the Gemini’s Orbital Attiude and Maneuvering System (OAMS), Armstrong was able to arrest the rolling motion. However, once he let off the restoring thruster action, the combined vehicle began rolling again.

The crew’s next action was to turn off the Agena’s systems. The errant motion subsided. Several minutes elapsed with the control problem seemingly solved. Suddenly, the uncommanded motion of the still-docked pair started again. The crew noticed that the Gemini’s OAMS was down to 30% fuel. Could the problem be with the Gemini spacecraft and not the Agena?

The crew jettisoned the Agena. That didn’t help matters. The Gemini was now tumbling end over end at almost one revolution per second. The violent motion made it difficult for the astronauts to focus on the instrument panel. Worse yet, they were in danger of losing consciousness.

Left with no other alternative, Armstrong shut down his OAMS and activated the Reentry Control System reaction control system (RCS) in a desperate attempt to stop the dizzying tumble. The motion began to subside. Finally, Armstrong was able to bring the spacecraft under control.

That was the good news. The bad news for the crew of Gemini VIII was that the rest of the mission would now have to be aborted. Mission rules dictated that such would be the case if the RCS was activated on-orbit. There had to be enough fuel left for reentry and Gemini VIII had just enough to get back home safely.

Gemini VIII splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean 4,320 nm east of Okinawa. Mission elapsed time was 10 hours, 41 minutes and 26 seconds. Spacecraft and crew were safely recovered by the USS Leonard F. Mason.

In the aftermath of Gemini VIII, it was discovered that OAMS Thruster No. 8 had failed in the ON position. The probable cause was an electrical short. In addition, the design of the OAMS was such that even when a thruster was switched off, power could still flow to it. That design oversight was fixed so that subsequent Gemini missions would not be threatened by a reoccurence of the Gemini VIII anomaly.

Neil Armstrong and David Scott met their goliath in orbit and defeated the beast. Armstrong received a quality increase for his efforts on Gemini VIII while Scott was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Both men were awared the NASA Exceptional Service Medal.

More significantly, their deft handling of the Gemini VIII emergency elevated both Armstrong and Scott within the ranks of the astronaut corps. Indeed, each man would ultimately land on the Moon and serve as mission commander in doing so; Neil Armstrong on Apollo 11 and David Scott on Apollo 15.