Forty-eight years ago this month, the crew of Apollo 13 departed Earth and headed for the Fra Mauro highlands of the Moon. Less than six days later, they would be back on Earth following an epic life and death struggle to survive the effects of an explosion that rocked their spacecraft 200,000 miles from home.

Apollo 13 was slated as the 3rd lunar landing mission of the Apollo Program. The intended landing site was the mountainous Fra Mauro region near the lunar equator. The Apollo 13 crew consisted of Commander James A. Lovell, Jr., Lunar Module Pilot Fred W. Haise, Jr. and Command Module Pilot John L. (Jack) Swigert, Jr. Lovell was making his fourth spaceflight (second to the Moon) while Haise and Swigert were space rookies.

Apollo 13 lifted-off from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, 11 April 1970. The official launch time was 19:13:00 UTC (13:13 CST). During second stage burn, the center engine shutdown two minutes early as a result of excessive longitudinal structural vibrations. The outer four J-2 engines burned 34 seconds longer to compensate. Arriving safely in low Earth orbit, Lovell observed that every mission seemed to have at least one major glitch. Clearly, Apollo 13′s was now out of the way!

The Apollo 13 payload stack consisted of a Command Module (CM), Service Module (SM) and Lunar Module (LM). The entire ensemble had a lift-off mass of nearly 49 tons. In keeping with tradition, the Apollo 13 crew gave call signs to their Command Module and Lunar Modules. This helped flight controllers distinguish one vehicle from the other over the communications net during mission operations. The CM was named Odyssey and the LM was given the name of Aquarius.

The first two days of the outward journey to the Moon were uneventful. In fact, some at Mission Control in Houston, Texas seemed somewhat bored. The same could be said for the ever-astute press corps who predictably reported that Americans were now responding to the lunar landing missions with a collective yawn. The journalistic sages averred that the space program needed some pepping-up. Going to the Moon might have been impossible yesterday, but today its just run-of-the-mill stuff. Actually, it was all kind of easy. So wrote they of the fickle Fourth Estate.

It all started with a bang at 03:07:53 UTC on Tuesday, 14 April 1970 (21:07:53 CST, 13 April 1970) with Apollo 13 distanced 200,000 miles from Earth. “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” This terse statement from Jack Swigert informed Mission Control that something ominous had just occurred onboard Apollo 13. Jim Lovell reported that the problem was a “Main B Bus undervolt”. A potentially serious electrical system problem.

But what was the exact nature of the of problem and why did it occur? Nary a soul in the spacecraft nor in Mission Control could provide the answers. All anyone really knew at the moment was that two of three fuel cells formerly supplying electricity to the Command Module were now dead. Arguably more alarming, Oxygen Tank No. 2 was empty with Tank No. 1 losing oxygen at a high rate.

There was something else. The Apollo 13 reaction control system was firing in apparent response to some perturbing influence. But what was it? The answer came with all the subtlety of a sledge hammer blow. Jim Lovell reported that some kind of gas was venting from the spacecraft into space. That chilling observation suddenly explained why the No. 1 oxygen tank was losing pressure so rapidly.

Once Mission Control and the Apollo 13 astronauts fully comprehended the gravity of the situation, the entire team went to work to bring the spacecraft home. Odyssey was powered-down to conserve its battery power for reentry while Aquarius was powered-up and became a makeshift lifeboat. A major problem was that Aquarius had battery power and water sufficient for only 40 hours of flight. The trip home would take 90 hours.

Amazingly, engineering teams at Mission Control conceived and tested means to minimize electrical usage onboard Aquarius. However, the Apollo 13 crew would have to endure privation and hardships to survive. The cabin temperature in Aquarius got down to 38F and each man was permitted only six ounces of water per day. The walls of the spacecraft were covered with condensation. Sleep was almost impossible and fatigue became another relentless enemy to survival.

And then there was the build-up of carbon dioxide. The LM environmental system (EV) was designed to support two men. Now there were three. Between the CM and LM, there was an ample supply of lithium hydroxide canisters to scrub the gas from the cabin atmosphere for the trip home. However, the square CM canisters were incompatible with the circular openings on LM EV. The engineers on the ground invented a device to eliminate this compatibility using materials found onboard the spacecraft.

The Apollo 13 crew had to fire the LM descent motor several times in order to adjust their return trajectory. Use of the SM propulsion system to effect these firings was denied the crew due to concerns that the explosion could have damaged it. These rocket motor firings required precise inertial navigation. The star sightings required for celestial navigation were impossible to make owing to the huge cloud of debris surrounding the spacecraft. Means were devised to use the Sun as the primary navigational source.

While the nation and indeed the world looked on, the miracle of Apollo 13 slowly unfolded. Many a humble heart uttered a prayer for and in behalf of the trio of astronauts. Millions throughout the world followed the men’s journey home via newspaper, radio, television and other media.

As Apollo 13 approached the Earth, the overriding issue was whether the systems onboard Odyssey could be successfully brought back on line. The walls and instrument panels of the craft were drenched with condensation. Unquestionably, the electronics and wiring bundles behind those instrument panels were also soaking wet. Would they short-out once electrical energy flowed through them again? Would there be enough battery power for reentry?

Happily, the CM power-up sequence was successfully accomplished. Once again the resourceful engineers at Mission Control produced under extreme duress. They devised an intricate and never-attempted-in-flight power-up sequence for the CM. Too, the extra insulation added to the CM’s electrical system in the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire provided protection from condensation-induced electrical arcing.

Approximately four hours prior to reentry, the Apollo 13 crew jettisoned the SM. What they saw was shocking. The module was missing a complete external panel and most of the equipment inside was gone or significantly damaged. One hour prior to entry, Aquarius, their trusty space lifeboat, was also jettisoned. The only concern now was whether the Command Module base heat shield had survived the explosion intact.

On Friday, 17 April 1970, Odyssey hit entry interface (400,000 feet) at 36,000 feet per second. Other than a worrisome additional 33 seconds of plasma-induced communications blackout (4 minutes, 33 seconds total), the reentry was entirely nominal. Splashdown occurred at 18:07:41 UTC near American Samoa in the Pacific Ocean. The USS Iwo Jima quickly recovered spacecraft and crew.

The post-flight mishap investigation revealed that Oxygen Tank No. 2, located deep within the bowels of the SM, exploded when the crew conducted a cryo stir of its multi-phase contents. Unknown to all was the fact that a mismatch between the tank heater and thermostat had resulted in the Teflon insulation of the internal wiring being severely damaged during previous ground operations. This meant that the tank was now a bomb and would detonate its contents when used the next time. In this case, the next time was in flight. The warning signs were there, but went unheeded.

Apollo 13 never landed at Fra Mauro. And none of its crew would ever again fly in space. But in many ways, Apollo 13 was NASA’s finest hour. Overcoming myriad seemingly intractable obstacles in the aftermath of a completely unanticipated catastrophe, deep in trans-lunar space, will forever rank high among the legendary accomplishments of spaceflight. With essentially no margin for error and in the harsh glare of public scrutiny, NASA wrested victory from the tentacles of almost certain failure and brought three weary men safely back to their home planet.

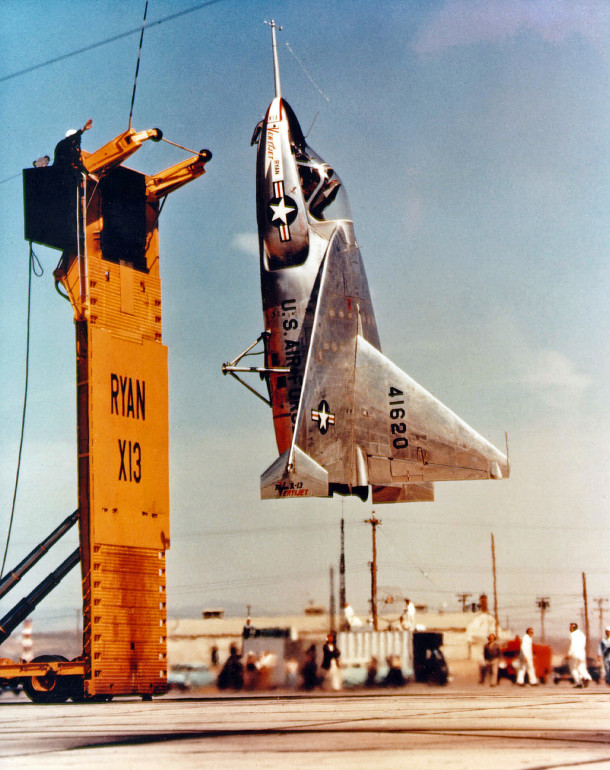

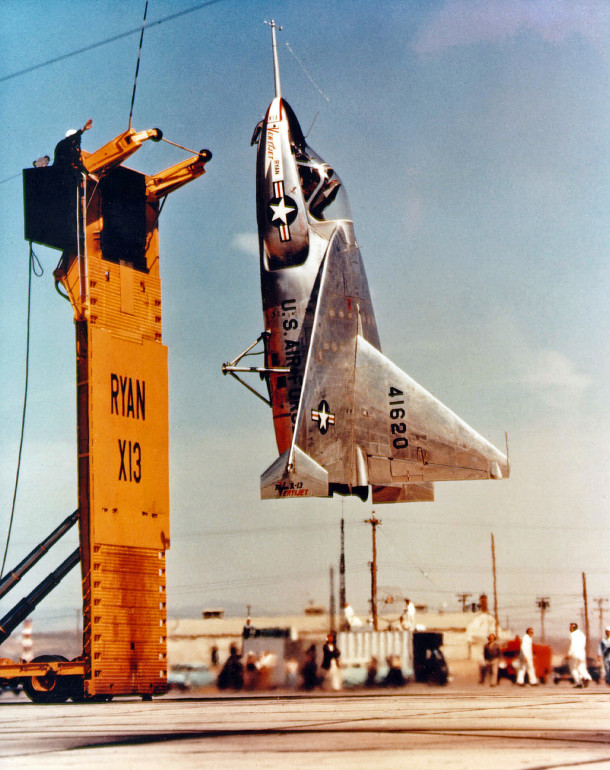

Sixty-two years ago this month, the USAF/Ryan X-13 Vertijet completed history’s first vertical-to horizontal-back to vertical flight of a jet-powered Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) aircraft. This event took place at Edwards Air Force Base, California with Ryan Chief Test Pilot Peter F. Girard at the controls.

The X-13 Vertijet was an experimental flight vehicle designed to determine the feasibility of a jet-powered Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) aircraft. The initial idea for the type dates back to 1947 when the United States Navy (USN) put Ryan under contract to explore the viability of a jet-powered VTOL aircraft. At the time, the Navy was quite interested in exploiting the VTOL concept for tactical advantage. The service envisioned basing VTOL aircraft on submarines and small surface ships.

The USN-Ryan team worked the X-13 VTOL concept for over six (6) years to good effect. While no flight vehicle took to the skies during that time, a great deal of progress was made in the realm of hovering flight using ground-based vertical test rigs. Particular effort was focused on VTOL low-speed flight controls. However, Navy research and development funding was slashed in the aftermath of the Korean War and the X-13 project ran out of money in the summer of 1953.

Fortunately, the United States Air Force (USAF) had become interested in the X-13 and the possibilities of VTOL flight prior to the Navy running out of money. The junior service assumed ownership of the X-13 effort after securing the funding required to continue the program. A pair of X-13 prototypes were subseqently built and flown by Ryan Aeronautical. These aircraft were assigned USAF serial numbers 54-1619 and 54-1620, respectively.

The X-13 measured 23.5 feet in length and had a wing span of 21 feet. The single-place aircraft featured a maximum take-off weight of approximately 7,300 pounds. Hovering flight control was provided via wing tip-mounted yaw and roll nozzles. The heart of the VTOL aircraft was its reliable Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet. The non-afterburning powerplant used standard JP-4 fuel and produced a maximum thrust of 10,000 pounds.

The X-13 was transported, launched and retrieved using a special flatbed trailer. Hinged at one end, the trailer was raised and lowered through the instrumentality of a pair of hydraulic rams. Once raised to a vertical position, the X-13 hung on its nose hook from a steel suspension cable stretched between two mechanical arms. Rather than landing gear, the aircraft sat on two non-retractable tubular bumpers positioned on the lower fuselage.

Flight testing of the No. 1 X-13 (S/N 54-1619) began on Saturday, 10 December 1955 at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The purpose of this initial flight was to test the X-13’s conventional flight characteristics. The aircraft was configured with tricycle landing to permit a runway take-off. Ryan Chief Test Pilot Peter F. “Pete” Girard flew a brief seven minute test hop in which he determined that the X-13 had serious control issues in all 3-axes. The subsequent installation of yaw and roll dampers fixed the problem.

The next phase of flight testing involved vertical hovering flight wherein aircraft handling and control characteristics were explored. For doing so, the X-13 was outfitted with a vertical landing gear system composed of a tubular support structure and a quartet of small caster-type wheels. Thus configured, the X-13 could take-off, hover and land in the vertical. As vertical flight testing progresed, important refinements were made to the aircraft’s turbojet throttling and reaction control systems.

The first vertical flight test was made on Monday, 28 May 1956 with the No. 1 aircraft. Pete Girard was again in the cockpit. Restricting maximum altitude to about 50 feet above ground level, Girard found the aircraft relatively easy to fly and land. Succeeding flight tests would ultimately include practice hook landings wherein a 1-inch thick manila rope suspended between a pair of 50-foot towers was engaged. A great deal of experience with and confidence in the X-13 system was accrued during these tests.

Prior to flying the X-13 all-up mission, an additional phase of flight testing was required which would culminate with the events of Monday, 28 November 1956. With the conventional landing gear installed on the No. 1 aircraft, Girard took-off from Edwards and climbed to 6,000 feet. He then slowly pitched the aircraft into the vertical and hovered for an extended period. Girard then executed a transition back to horizontal flight and landed. The first-ever horizontal-to vertical-back to horizontal flight transition was entirely successful.

The big day came on Thursday, 11 April 1957. Edwards Air Force Base again served as the test site. This time using the No. 2 X-13 (S/N 54-1620), Pete Girard took-off vertically, ascended in hovering flight and transitioned to conventional flight. Following a series of standard flight maneuvers, Girard transitioned the aircraft back into a vertical hover, descended and engaged the suspension cable on the support trailer with the aircraft’s nose hook. The first-ever vertical-to horizontal-back to vertical flight of a jet-propelled VTOL aircraft was history.

Both X-13 aircraft would go on to successfully conduct additional flight testing and stage numerous flight demonstrations during the remainder of 1957. However, innovative and impressive as it was, the X-13 did not garner the advocacy and backing required to proceed to production. A combination of bad timing, a risk averse military and combat performance limitations resulted in the aircraft and its technology quickly fading from the aviation scene.

Remarkably, both X-13 aircraft survived the type’s flight test program. The No. 1 aircraft (S/N 54-1619) is displayed at the San Diego Aerospace Museum in San Diego, California. The No. 2 X-13 aircraft (S/N 54-1620) is on display in the Research and Development Gallery of the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Sixty years ago this week, NASA held a press conference in Washington, D.C. to introduce the seven men selected to be Project Mercury Astronauts. They would become known as the Mercury Seven or Original Seven.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. The overall objective of Project Mercury was to place a manned spacecraft in Earth orbit and bring both man and machine safely home. Project Mercury ran from 1959 to 1963.

The men who would ultimately become Mercury Astronauts were among a group of 508 military test pilots originally considered by NASA for the new role of astronaut. The group of 508 candidates was then successively pared to 110, then 69 and finally to 32. These 32 volunteers were then subjected to exhaustive medical and psychological testing.

A total of 18 men were still under consideration for the astronaut role at the conclusion of the demanding test period. Now came the hard part for NASA. Each of the 18 finalists was truly outstanding and would be a worthy finalist. But there were only 7 spots on the team.

On Thursday, 09 April 1959, NASA publicly introduced the Mercury Seven in a special press conference held for this purpose at the Dolley Madison House in Washington, D.C. The men introduced to the Nation that day will forever hold the distinction of being the first official group of American astronauts. In the order in which they flew, the Mercury Seven were:

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr., United States Navy. Shepard flew the first Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-3) on Friday, 05 May 1961. He was also the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Shepherd did so as Commander of Apollo 14 (AS-509) in February 1971. Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia on 21 July 1998 at the age of 74.

Vigil Ivan Grissom, United States Air Force. Grissom flew the second Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-4) on Friday, 21 July 1961. He was also Commander of the first Gemini mission (GT-3) in March 1965. Gus Grissom might very well have been the first man to walk on the Moon. But he died in the Apollo 1 Fire, along with Astronauts Edward H. White II and Roger Chaffee, on Friday, 27 January 1967. Gus Grissom was 40 at the time of his death.

John Herschel Glenn Jr., United States Marines. Glenn was the first American to orbit the Earth (MA-6) on Thursday, 22 February 1962. He was also the only Mercury Astronaut to fly a Space Shuttle mission. He did so as a member of the STS-95 crew in October of 1998. Glenn was 77 at the time and still holds the distinction of being the oldest person to fly in space. John Glenn was the last member of the Mercury Seven to depart this earth when he passed away in December 2016 at the age of 95.

Seventy-six years ago this week, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most haunting and intriguing stories in the annals of aviation history. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.