Forty-seven years ago this month, three American astronauts became the first men to orbit the Earth’s Moon during the flight of Apollo 8. This epic mission also featured the first manned flight of the mighty Saturn V launch vehicle as well as history’s first superorbital entry of a manned spacecraft.

Following the Apollo 1 tragedy in January of 1967, the United States would not fly another manned space mission until October 1968. That flight, Apollo 7, was a highly successful earth-orbital mission in which the new Block II Apollo Command Module was thoroughly flight-proven.

Notwithstanding Apollo 7’s accomplishments, only 14 months remained for the United States to meet the national goal of achieving a manned lunar landing before the end of the 20th century’s 7th decade. The view held by many in late 1968 was that an already daunting task was now unachievable in the narrow window of time that remained to accomplish it.

The pessimism about reaching the Moon before the end of the decade was easy to understand. The Saturn V moon rocket had not been man-rated. The Lunar Module had not flown. Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) was untried. Men had not even so much as orbited the Moon. Yet, history would record that the United States would find a way to accomplish that which had never before been achieved.

George Low, manager of NASA’s Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, came up with the idea. Low proposed that the first manned flight of the Saturn V be a trip all the way to the Moon. It was something that Low referred to as the “All-Up Testing” concept. The newly-conceived mission would be flown in December 1968 near Christmas time.

While initially seen as too soon and too risky by many in NASA’s management hierarchy, Low’s bold proposal was ultimately accepted as the only way to meet the national lunar landing goal. Yes, there was additional risk. However, the key technologies were ready, the astronauts were willing, and the risk was tolerable.

Apollo 8 lifted-off from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Saturday, 21 December 1968 at 12:51 hours UTC. The crew consisted of NASA astronauts Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, Jr. and William A. Anders. Their target – the Moon – was 220,000 miles away.

After a 69-hour outbound journey, Apollo 8 entered lunar orbit on Tuesday, 24 December 1968 – Christmas Eve. The Apollo 8 crew photographed the lunar surface, studied the geologic features of its terrain, and made other observations from a 60-nautical mile circular orbit. The spacecraft circled the Moon 10 times in slightly over 20 hours.

The most poignant and memorable event in Apollo 8′s historic journey occurred on Christmas Eve night when each of the flight crew took turns reading from the Book of Genesis in the Holy Bible. The solemnity of the moment was evident in the voices of the astronauts. They had seen both the Moon and the Earth from a perspective that none before them had. Fittingly, they expressed humble reverence for the Creator of the Universe on the anniversary of the birth of mankind’s Redeemer.

Apollo 8 departed lunar orbit a little over 89 hours into the mission. Following a nearly 58-hour inbound trip, Apollo 8 reentered the earth’s atmosphere at 36, 221 feet per second on Friday, 27 December 1968. The first manned superorbital reentry was performed in total darkness. It was entirely successful as Apollo 8 landed less than 1 nautical mile from its target in the Pacific Ocean. The USS YORKTOWN effected recovery of the weary astronauts and their trustworthy spacecraft. Mission total elapsed time was 147 hours and 42 seconds.

The year 1968 was a tumultuous one for the United States of America. Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated. American military blood flowed on the battlefields of Vietnam and civilian blood was let in countless demonstrations taking place in the nation’s cities. The ill-posed sexual revolution continued to eat away at the country’s moral moorings.

But, as is so often the case, an event from the realm of flight, now newly extended to lunar space, reminded us of our higher nature and potential. For a too brief moment, Apollo 8 put our collective purpose for being here into sharp focus. Perhaps a short phrase in a telegram sent to Frank Borman from someone he had never met said it best: “You saved 1968!”

However, looking through the lens of history, we now know that Apollo 8 did much more than end the penultimate year of the 1960’s on a positive note. Indeed, it may be said that Apollo 8 saved the entire Apollo Program.

Fifty years ago this month, Gemini 7 set a new record for long-duration manned spaceflight. The official lift-off-to-splashdown flight duration was 330 hours, 35 minutes and 1 second or nearly fourteen days.

Project Gemini was the critical bridge between America’s fledgling manned spaceflight effort – Project Mercury – and the bold push to land men on the Moon – Project Apollo. While the events and importance of this program have faded with the passage of time, there would have been no manned lunar landing in the decade of the 1960′s without Project Gemini.

On Thursday, 25 May 1961, President John F. Kennedy addressed a special session of the U.S. Congress on the topic of “Urgent National Needs”. Near the end of his prepared remarks, President Kennedy proposed that the United States “should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

At the time of the President’s clarion call to go to the Moon, the United States had accrued a total of 15 minutes of manned spaceflight experience. That quarter hour of space faring activity had come just 20 days previous. Indeed, Alan B. Shepard became the first American to be launched into space when he rode his Freedom 7 Mercury spacecraft on a sub-orbital trajectory down the Eastern Test Range on Tuesday, 05 May 1961.

America responded enthusiastically to the manned lunar landing goal. However, no one really knew exactly how to go about it! After considering several versions of direct ascent from the Earth to the Moon, NASA ultimately decided to use a method proposed by engineer John C. Houbolt known as Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR). As a result, NASA would have to invent and master the techniques of orbital rendezvous.

Project Gemini provided the technology and flight experience required for a manned lunar landing and return. In the 20 months between March of 1965 and November of 1966, a total of 10 two-man Gemini missions were flown. During that time, the United States learned to navigate, rendezvous and dock in space, fly for long durations and perform extra-vehicular activities.

The primary purpose of Gemini 7 was to conduct a 14-day orbital mission. This was important since the longest anticipated Apollo mission to the Moon and back would be about the same length of time. Gemini 7 was flown to show that men and spacecraft could indeed function in space for the required period. A secondary goal of Gemini 7 was to serve as the target for Gemini 6 in achieving the world’s first rendezvous between two manned spacecraft.

Gemini-Titan Seven (GT-7) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 19:30:03 UTC on Saturday, 04 December 1965. The Gemini 7 flight crew consisted of Commander Frank F. Borman II and Pilot James A. Lovell, Jr. The astronauts were successfully inserted into a 177-nm x 87-nm low-earth orbit. This initial orbit was later circularized to 162-nm.

Borman and Lovell spent the first 10-days of their mission conducting a variety of space experiments. They wore special lightweight spacesuits that were supposed to improve comfort level for their long stay in space. However, these suits were not all that comfortable and by their second week in space, the astronauts were flying in just their long-johns.

On their 11th day in space, the Gemini 7 crew had visitors. Indeed, Gemini 6 was launched into Earth orbit from Cape Canaveral and subsequently executed the first rendezvous in space with Gemini 7 on Wednesday, 15 December 1965. Gemini 6, with Commander Walter M. Schirra, Jr. and Pilot Thomas P. Stafford on board, ultimately maneuvered to within 1 foot of the Gemini 7 spacecraft.

While Gemini 6 returned to Earth within 24 hours of launch, Gemini 7 and her weary crew soldiered on. The monotony was brutal. Borman and Lovell had conducted all of their planned space experiments. They had to drift through space to conserve fuel. They couldn’t sleep because they weren’t tired. Borman later indicated that those last 3 days on board Gemini 7 were some of the toughest of his life.

On the 14th day of flight, Saturday, 18 December 1965, Borman and Lovell successfully returned to Earth. Reentry was entirely nominal. Splashdown occurred at 14:05:04 UTC in the Atlantic Ocean roughly 400 miles east of Nassau in The Bahamas. Crew and spacecraft were recovered by the USS Wasp.

Frank Borman and Jim Lovell had orbited the Earth 206 times during their 14-day mission. Each crew member was tired and a little unsteady as he walked the flight deck of the recovery ship. However, each man quickly recovered his native strength and vitality.

The 14 days that the Gemini 7 crew spent in space were physically and emotionally demanding. Life within the cramped confines of their little spacecraft was akin to two guys living inside a telephone booth for two weeks. Notwithstanding the challenges of that demanding existence, the Gemini 7 crew did their job. Gemini 7 was a resounding success. More, Project Gemini had achieved another key milestone. The Moon now seemed a bit closer.

Fifty-six years ago today, USAF Captain Joe B. Jordan zoomed a modified USAF/Lockheed F-104C Starfighter to a world altitude record of 103,395.5 feet above mean sea level. The flight originated from and recovered to the Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC) at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

On Tuesday, 14 July 1959, the USSR established a world altitude record for turbojet-powered aircraft when Soviet test pilot Vladimir S. Ilyushin zoomed the Sukhoi T-43-1 (a prototype of the Su-9) to an absolute altitude of 94,661 feet. By year’s end, the Soviet achievement would be topped by several American aircraft.

FAI rules stipulate that an existing absolute altitude record be surpassed by at least 3 percent for a new mark to be established. In the case of the Soviet’s 1959 altitude record, this meant that an altitude of at least 97,501 feet would need to be achieved in a record attempt.

On Sunday, 06 December 1959, USN Commander Lawrence E. Flint wrested the months-old absolute altitude record from the Soviets by zooming to 98,561 feet. Flint piloted the second USN/McDonnell Douglas YF4H-1 (F4 Phantom II prototype) in accomplishing the feat. In a show of inter-service cooperation, the record flight was made from the AFFTC at Edwards Air Force Base.

Meanwhile, USAF was feverishly working on its own record attempt. The aircraft of choice was the Lockheed F-104C Starfighter. However, with the record now held by the Navy, the Starfighter would have to achieve an absolute altitude of at least 101,518 feet to set a new mark. (Per the FAI 3 percent rule.)

On Tuesday, 24 November 1959, the AFFTC accepted delivery of the record attempt aircraft, F-104C (S/N 56-0885), from the Air Force Special Weapons Center at Kirtland AFB in New Mexico. This aircraft was configured with a J79-GE-7 turbojet capable of generating nearly 18,000 pounds of sea level thrust in afterburner.

Modifications were made to the J79 to maximize the aircraft’s zoom kinematic performance. The primary enhancements included increasing afterburner fuel flow rate by 10 percent and maximum RPM from 100 to 103.5 percent. Top reset RPM was rated at 104.5 percent. Both the ‘A’ and ‘B’ engine flow bypass flaps were operated in the open position as well. These changes provided for increased thrust and stall margin.

An additional engine mod involved reducing the minimum engine fuel flow rate from 500 to 250 pounds per hour. Doing so increased the altitude at which the engine needed to be shut down to prevent overspeed or over-temperature conditions. Another change included increasing the maximum allowable compressor face temperature from 250 F to 390 F.

The F-104C external airframe was modified for the maximum altitude mission as well. The compression cones were lengthened on the bifurcated inlets to allow optimal pressure recovery at the higher Mach number expected during the record attempt. High Mach number directional stability was improved by swapping out the F-104C empannage with the larger F-104B tail assembly.

USAF Captain Joe B. Jordan was assigned as the altitude record attempt Project Pilot. USAF 1st Lt and future AFFTC icon Johnny G. Armstrong was assigned as the Project Engineer. Following an 8-flight test series to shake out the bugs on the modified aircraft, the record attempt proper started on Thursday, 10 December 1959.

On Monday, 14 December 1959, F-104C (S/N 56-0885) broke the existing absolute altitude record for turbojet-powered aircraft on its 5th attempt. Jordan did so by accelerating the aircraft to Mach 2.36 at 39,600 feet. He then executed a 3.15-g pull to an inertial climb angle of 49.5 degrees. Jordan came out of afterburner at 70,000 feet and stop-cocked the J79 turbojet at 81,700 feet.

Roughly 105 seconds from initiation of the pull-up, Joe Jordan reached the top of the zoom. The official altitude achieved was 103,395.5 feet above mean sea level based on range radar and Askania camera tracking. True airspeed over the top was on the order of 455 knots. Jordan started the pull-up to level flight at 60,000 feet; completing the recovery at 25,000 feet. Landing was entirely uneventful.

Jordan’s piloting achievement in setting the new altitude record was truly remarkable. His conversion of kinetic energy to altitude (potential energy) during the zoom was extremely efficient; realizing only a 2.5 percent energy loss from pull-up to apex. Jordan also exhibited exceptional piloting skill in controlling the aircraft over the top of the zoom where the dynamic pressure was a mere 14 psf. He did so using aerodynamic controls only. The aircraft did not have a reaction control system ala the X-15.

Armstrong’s contributions to shattering the existing altitude record were equally substantial. Skillful flight planning and effective use of available resources (including time available for the record attempt) were pivotal to mission success. Armstrong significantly helped maximize aircraft zoom performance through proper selection of pull-up flight conditions and intelligent use of accurate day-of-flight meteorological information.

For his skillful piloting efforts in setting the world absolute altitude record for turbojet-powered aircraft in December of 1959, Joe Jordan received the 1959 Harmon Trophy.

Sixty-two years ago this week, USAF Major Charles E. Yeager set an unofficial world speed record of 1,650 mph (Mach 2.44) in the Bell X-1A flight research aircraft. In the process, the legendary test pilot very nearly lost his life.

The USAF/Bell X-1A was a second generation X-aircraft intended to explore flight beyond Mach 2. It measured 35.5 feet in length and had a wing span of 28 feet. Gross take-off weight was 16,500 pounds.

Like its XS-1 forebear, the X-1A was powered by an XLR-11 rocket motor which produced a maximum sea level thrust of 6,000 lbs. The XLR-11 burned 9,200 pounds of propellants (alcohol and liquid oxygen) in roughly 270 seconds of operation.

Departing Edwards Air Force Base, California on Saturday, 12 December 1953, Yeager and the X-1A (S/N 48-1384) were carried to altitude by a USAF B-29 mothership (S/N 45-21800 ). X-1A drop occurred at 240 knots and 30,500 feet. Within ten seconds, Yeager lit off three of the XLR-11’s four rocket chambers and started to climb upstairs.

Yeager fired the 4th chamber of the XLR-11 passing through 43,000 feet and initiated a pushover at 62,000 feet. The maneuver was completed at 76,000 feet; higher than planned. In level flight now and traveling at Mach 1.9, the X-1A continued to accelerate in the thin air of the stratosphere.

Yeager quickly exceeded Scott Crossfield’s briefly-held Mach 2.005 record set on Friday, 20 November 1953. However, he now had to be very careful. Wind tunnel testing had revealed that the X-1A would be neutrally stable in the directional channel as it approached Mach 2.3.

As Yeager cut the throttle around Mach 2.44, the X-1A started an uncommanded roll to the left. Yeager quickly countered with aileron and rudder. The X-1A then rapidly rolled right. Full aileron and opposite rudder failed to control the roll. After 8 to 10 complete revolutions, the aircraft ceased rolling, but was now inverted.

In an instant, the X-1A started rolling left and then went divergent in all three axes. The aircraft tumbled and gyrated through the sky. Control inputs had no effect. Yeager was in serious trouble. He could not control his aircraft and punching-out was not an option. The X-1A had no ejection seat.

Chuck Yeager took a tremendous physical and emotional beating for more than 70 seconds as the X-1A wildly tumbled. Normal acceleration varied between plus-8 and negative 1.3 G’s. His helmet hit the canopy and cracked it. He struck the control column so hard that it was physically bent. His frantic air-to-ground communications were distinctly those of a man who was convinced that he was about to die.

As the X-1A tumbled, it decelerated and lost altitude. At 33,000 feet, a battered and groggy Yeager found himself in an inverted spin. The aircraft suddenly fell into a normal spin from which Yeager recovered at 25,000 feet over the Tehachapi Mountains situated northwest of Edwards. Somehow, Yeager managed to get himself and the X-1A back home intact.

The culprit in Yeager’s wide ride was the then little-known phenomenon identified as roll inertial coupling. That is, inertial moments produced by gyroscopic and centripetal accelerations overwhelmed aerodynamic control moments and thus caused the aircraft to depart controlled flight. Roll rate was the critical mechanism since it coupled pitch and yaw motion.

The X-1A held the distiction of being the fastest-flying of the early X-aircraft until the Bell X-2 reached 1,900 mph (Mach 2.87) in July of 1956. Yeager’s harrowing experience in December 1953 would be his last flight at the controls of a rocket-powered X-aircraft. For his record-setting X-1A mission, he was awarded the 1953 Harmon Trophy.

Fifty-six years ago this month, a USAF/Convair F-106A Delta Dart interceptor was clocked at 1,525.695 mph on an 11-mile straight course at Edwards Air Force Base, California. This mark still stands as an absolute speed record for a single-engine turbojet-powered aircraft.

The USAF/Convair F-106 Delta Dart was designed for the all-weather interceptor role in defense of CONUS. As such, the Delta Dart’s primary mission was to seek out Soviet bomber formations and destroy same using its internally-carried missiles. Armament consisted of either (1) a quartet of Hughes AIM-4 Falcon missiles and a single AIM-26A Falcon missile or (2) a single Douglas AIR-2 Genie missile.

A member of the fabled Century Series, the Delta Dart was produced in two variants. The single place version was known as the F-106A while the dual place version was designated as the F-106B. Though primarily a trainer, this aircraft was also combat-capable. A total of 340 Delta Dart aircraft were manufactured by Convair; 277 F-106A’s and 63 F-106B’s.

The F-106A Delta Dart measured 70.7 feet in length and had a wing span of 38.25 feet. Gross Take-Off Weight (GTOW) and Empty Weight were 34,510 lbs and 24,420 lbs, respectively. Power was supplied by a single Pratt and Whitney J75-17 afterburning turbojet which produced 24,500 lbs of thrust at sea level.

The sleek Delta Dart was aerodynamically very clean. This was due in large measure to use of fuselage area ruling and a thin delta planform wing. The F-106A could climb at 29,000 feet per minute and had a service ceiling of 57,000 feet. Maximum unrefueled range was on the order of 2,700 nm.

Due to its impressive performance, USAF employed the F-106A in an attempt to regain the single-engine absolute speed record from the Soviets in late 1959. The existing record of 1,483.84 mph had been established in 1956 by a Soviet Ye-66 aircraft specially designed for setting the speed mark. The Air Force’s absolute speed record attempt was codenamed Project Firewall.

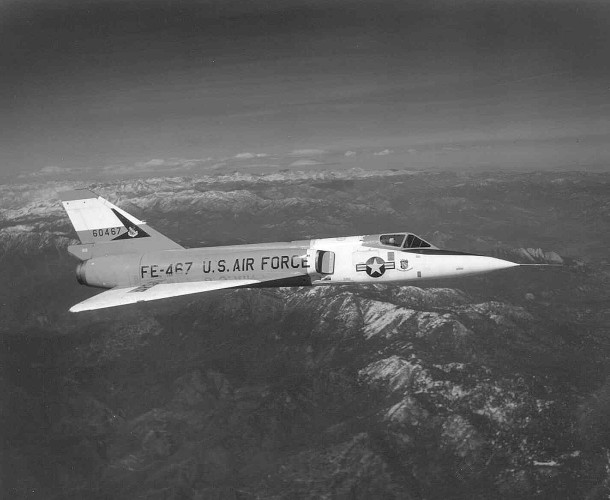

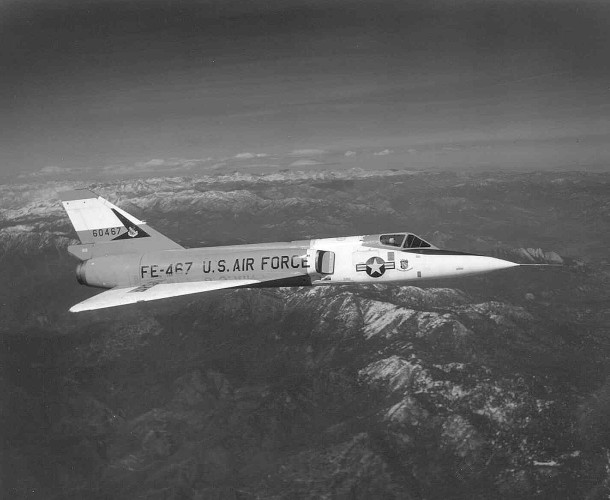

USAF originally selected F-106A (S/N 56-0459) to make the 1959 absolute speed record attempt. The aircraft was modified slightly to optimize its speed performance. However, 56-0459 experienced engine compressor stall problems and did not set the actual record. Rather, an unmodified F-106A (S/N 56-0467) was called into service and set the speed record reported here.

On Tuesday, 15 December 1959, USAF Major Joseph W. Rogers departed Edwards Air Force Base in a quest to establish a new absolute speed record for a single-engine turbojet-powered aircraft. Flying at 40,000 feet, Rogers and his F-106A averaged 1,525.695 mph over an 11-mile straight course to set a new speed mark.

For his remarkable airmanship on Project Firewall, Joe Rogers was presented with the Distinguished Flying Cross, the DeLavaulx Medal, and the Thompson Trophy. Rogers went on to a remarkable military career spanning 29 years. He retired in 1975 as a full colonel.

For its part, the Delta Dart went on to a 28-year operational life (1959-1987) with the United States Air Force and the Air National Guard. Considered by many to be the finest interceptor in aviation history, the Delta Dart is known to this day as the Ultimate Interceptor.