Sixty-one years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, triumph quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 mothership at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the X-2′s forebody and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, it was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded it in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

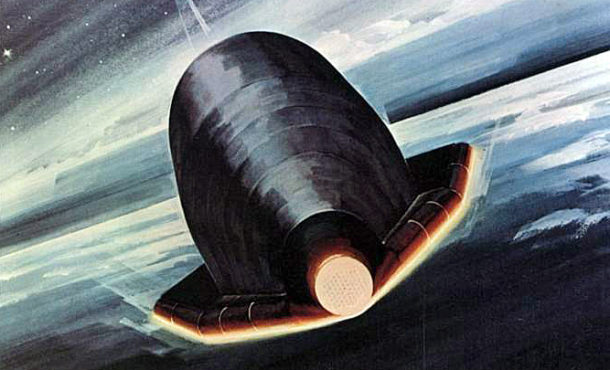

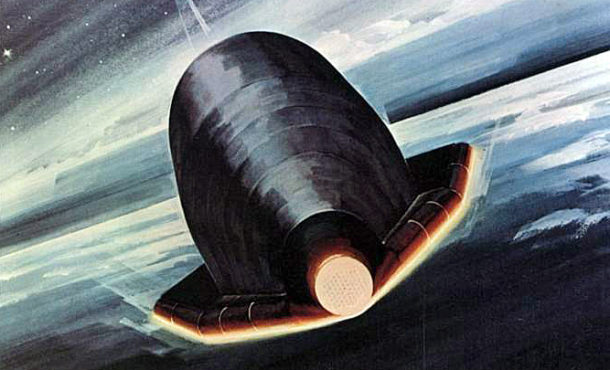

Fifty-four years ago today, the first ASSET flight test vehicle (ASV-1) successfully flew 1,600 nm down the Eastern Test Range (ETR) following launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Boosted atop a Thor launch vehicle, the hypersonic glider reached a maximum velocity of 10,900 mph (Mach 12).

The Aerothermodynamic/Elastic Structural Systems Environmental Tests (ASSET) Program was a United State Air Force flight research effort aimed at exploring hypersonic lifting entry. Programmatic objectives included evaluation of hypersonic lifting vehicle (1) reentry aerodynamic and aerothermodynamic phenomena (2) structural design concepts, and (3) panel flutter characteristics and body flap oscillatory pressures.

The basic ASSET vehicle configuration was a 70-deg delta planform wing with highly-radiused leading edges. The windward surface of this wing was flat and had a 10-deg break in slope roughly two-thirds of the way back from the nose. A blunted cone-cylinder combination was raked into the leeward surface of the wing to form the fuselage of the vehicle. The aft portion of the vehicle was terminated with a flat base region.

There were two (2) types of ASSET flight vehicles. The Aerothermoelastic Vehicle (AEV) variant was flown to investigate windward panel flutter characteristics and body flap oscillatory pressures. A pair of these vehicles were flown. Each weighed AEV weighed 1,225 lbs and was launched into a suborbital flight path by a Douglas Thor booster.

The Aerothermodynamic Structural Vehicle (ASV) variant was flown to determine external airframe surface temperature, heat flux and pressure distributions in hypersonic flight. These data were used to evaluate materials and structural concepts under reentry conditions. A quartet of these vehicles were flight tested. Each ASV weighed 1,130 lbs and was boosted by a Thor-Delta launch vehicle.

ASSET vehicles were boosted to altitudes between 168 KFT and 225 KFT depending on mission type. AEV entry insertion velocity was roughly 13,000 ft/sec while that for ASV shots varied between 16,000 and 19,500 ft/sec. ASSET performed hypersonic flight maneuvers via a combination of aerodynamic and propulsive controls. The windward-mounted body flap was the lone aerodynamic control surface while a set of 3-axis attitude control thrusters were located in the vehicle’s base region.

The first flight of the ASSET Program (ASV-1) took place on Wednesday, 18 September 1963. ASV-1 lift-off occurred at 09:39 UTC from Cape Canaveral’s LC-17B. Due to booster availability issues, a Thor DSV-2F launch vehicle was used for this mission rather than the higher energy Thor-Delta DSV-2G. Insertion altitude and velocity were 203,200 ft and 16,125 ft/sec, respectively. The ASV-1 mission was highly successful with the exception that the vehicle was lost when it sunk in the South Atlantic during recovery operations.

ASV-1 represented the first time in aerospace history that a lifting vehicle configuration had successfully flown a double-digit Mach number reentry trajectory. Five (5) more ASSET vehicles would fly before completion of the flight research program. The sixth and last mission occurred on Tuesday, 23 February 1965.

The ASSET Program garnered a wealth of first-ever hypersonic vehicle aerodynamic, aerothermodynamic, aerothermoelastic and flight controls data. This priceless information and the valuable experience gained during ASSET contributed significantly to the design and flight testing of the PRIME SV-5D and Space Shuttle Orbiter.

Strangely, only one of the ASSET flight test articles was ever recovered successfully. In particular, ASV-3 was recovered following its 1,800 nm suborbital flight down the Eastern Test Range on Wednesday, 22 July 1964. The recovered airframe is currently on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

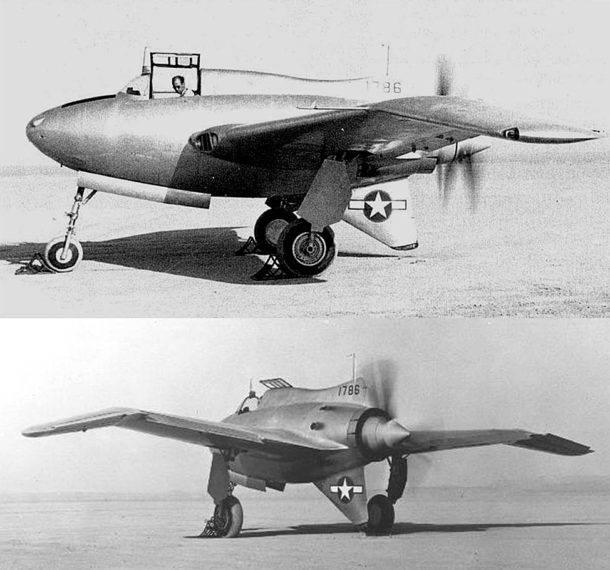

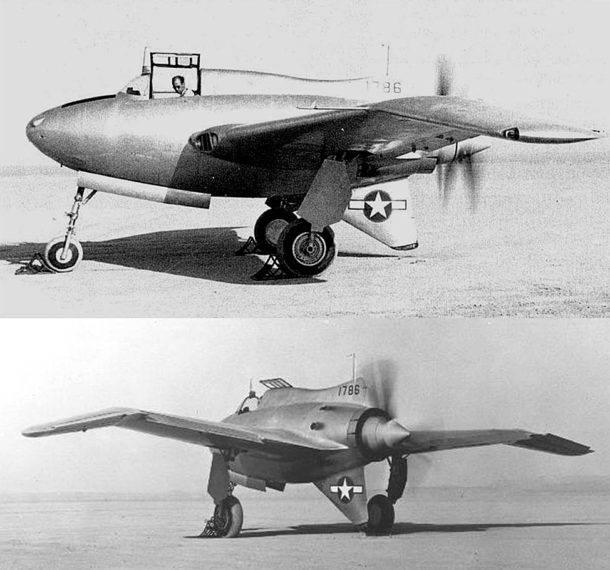

Seventy-four years ago this month, flight testing of the USAAF/Northrop XP-56 Black Bullet commenced at Army Air Base, Muroc in California. Northrop Chief Test Pilot John W. Myers was at the controls of the experimental pursuit aircraft.

The XP-56 (X for Experimental, P for Pursuit) was an attempt at producing a combat aircraft that had superior speed performance relative to conventional fighter-like airframes of the early 1940’s. Towards this end, designers sought to maximize thrust and minimize weight and aerodynamic drag. The product of their labors was a truly strange aircraft configuration.

The XP-56 was essentially a hybrid flying wing to which was added a stubby fuselage to house the pilot and engine. Power was provided by a single Pratt and Whitney R-2800 radial piston engine driving contra-rotating propellers. A pusher power plant installation was selected in the interest of reducing forebody drag. Gross Take-Off Weight (GTOW) came in at 11,350 lbs.

The XP-56’s wing featured a leading edge sweep of 32 degrees and a span of 42.5 feet. The tiny fuselage length of 27.5 feet necessitated the use of elevons for pitch and roll control. Aft-mounted dorsal and ventral tails contributed to directional stability while yaw control was provided by a rudder mounted in the ventral tail.

Under contract to the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), Northrop built a pair of XP-56 airframes; Ship No. 1 (S/N 41-786) and Ship No. 2 (S/N 42-38353). Top speed was advertised as 465 mph at 25,000 feet while the design service ceiling was estimated to be around 33,000 feet. The XP-56 was a short-legged aircraft, having a predicted range of only 445 miles at 396 mph.

XP-56 Ship No. 1 took to the air for the first time on Monday, 06 September 1943. The scene was Rogers Dry Lake at Army Air Field, Muroc (today’s Edwards Air Force Base) in California. Northrop Chief Test Pilot John W. Myers had the distinction of piloting the XP-56. As described below, this distinction was dubious at best.

Myers actually flew XP-56 Ship No. 1 twice on the type’s inaugural day of flight testing. The first flight was really just a hop in the air. Using caution as a guide, Myers flew only 5 feet off the deck in a 30 second flight that covered a distance on the order of 1 mile. The aircraft registered a top speed 130 mph. While the XP-56 exhibited a nose-down pitch tendency as well as lateral-directional sensitivities, Myers was able to complete the flight.

The XP-56’s second foray into the air nearly ended in disaster. Shortly after lift-off at 130 mph, the XP-56 presented pilot Myers with a multi-axis control problem about 50 feet above the surface of Rogers Dry Lake. The strange-looking ship simultaneously yawed to the left, rolled to the right, and pitched down. Holding the control stick with both hands, it was all the Northrop Chief Test Pilot could do keep the nose up and prevent the XP-56 from diving into the ground.

Myers attempted to throttle-back as his errant steed passed through 170 mph. The anomalous yawing-rolling-pitching motions reappeared at this point, once again testing Myers’ piloting skills to the max. The intrepid pilot was finally able to get the XP-56 back on the ground. Albeit, the landing was more of a controlled crash. All of this excitement took place in about 60 seconds over a two mile stretch of Rogers Dry Lake. John Myers had certainly earned his flight pay for the day.

XP-56 Ship No. 1 was demolished during a take-off accident on Friday, 08 October 1943. Although he sustained minor injuries, Myers survived the incident thanks largely to wearing an old polo helmet to protect his valuable cranium. Following the mishap , Myers said that “the airplane wanted to fly upside down and backwards, and finally did!”

XP-56 Ship No. 2 flew a total of ten (10) flights between March and August of 1944. Northrop test pilot Harry Crosby did the piloting honors this time around. Like Myers, Crosby had his hands full trying to fly the XP56. However, Crosby was able to coax the XP-56 up to 250 mph.

Despite valiant attempts to rectify the XP-56’s curious and dangerous handling qualities, Northrop engineers were never able to satisfactorily correct the little beast’s ills. This, coupled with the facts that the XP-56 (1) did not deliver the promised speed performance and (2) was being eclipsed by rapid developments in aircraft technology, the strange aerial concoction became a faded memory by 1945.

A final thought. Just why the XP-56 was given the nickname of Black Bullet is not clear. Ship No. 1 was bare metal and thus silver in appearance. Ship No. 2 sported a dark grey and green camouflage paint scheme. The Bullet moniker could be in deference to the bullet-like nose of the fuselage. In the final analysis, the name Black Bullet probably just sounded cool and evoked a stirring image of a bullet speeding to the target!

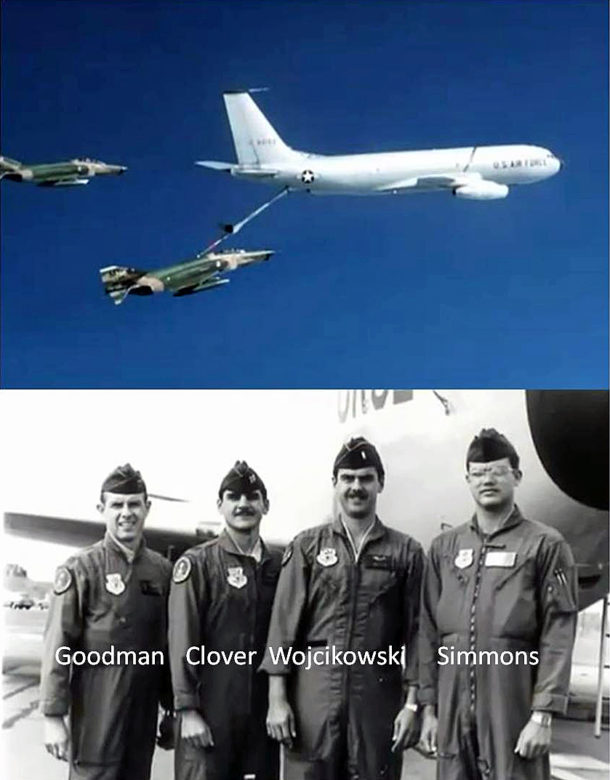

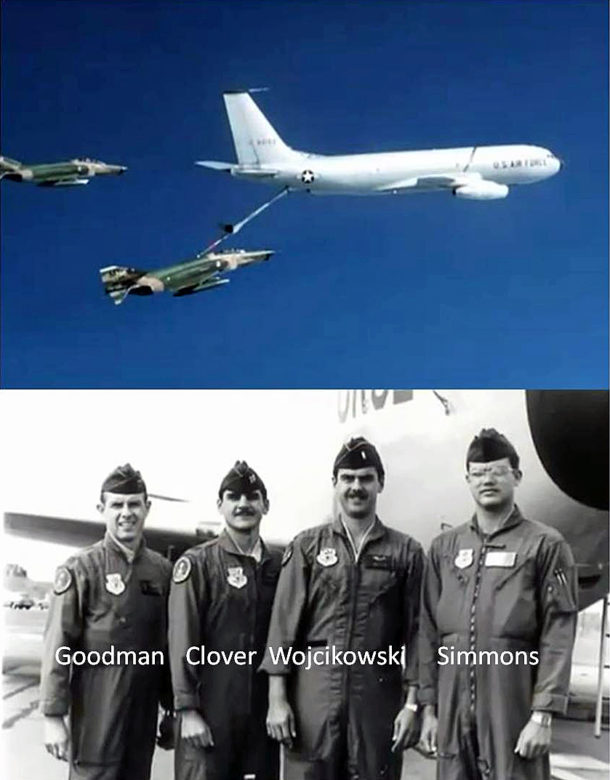

Thirty-four years ago today, the valiant crew of a USAF KC-135 Stratotanker performed multiple aerial refuelings of a stricken USAF F-4E Phantom II over the North Atlantic Ocean. Conducted under extremely perilous flight conditions, the remarkable actions of the aerial tanker’s crew allowed the F-4E to remain aloft long enough to safely divert to an alternate landing field.

On Monday, 05 September 1983, a pair of USAF F-4E Phantom II fighter-bombers departed the United States for a routine flight to Germany. To negotiate the trans-atlantic distance, the F-4E’s would require aerial refueling. As they approached the refueling rendezvous point, one of the aircraft developed trouble with its No. 2 engine. Though still operative, the engine experienced a significant loss of thrust.

The problem with the Phantom’s engine caused it to lose speed and altitude. Further, its No. 1 engine began to overheat as it tried to keep the aircraft airborne. As if this were not enough, the aircraft’s starboard hydraulic system became inoperative. Coupled with the fact that the fuel gauge was edging toward empty, the specter of an ejection and parachute landing in the cold Atlantic looked all but certain for the F-4E crew.

Enter the venerable KC-135 Stratotanker and her crew of Captain Robert J. Goodman, Captain Michael R. Clover, 1st Lt Karol R. Wojcikowski and SSgt Douglas D. Simmons. Based with the 42nd Aerial Refueling Squadron, their immediate problem was two-fold. First, locate and navigate to the pair of F-4E aircraft flying somewhere over the open ocean. Second, get enough fuel to both aircraft so the latter could complete their trans-atlantic hop. Time was of the essence.

Following execution of the rendezvous, the KC-135 crew needed to get their steed out in front of the fuel-hungry Phantoms. The properly operating Phantom quickly took on a load of fuel. However, the stricken aircraft continued to lose altitude as its pilot struggled just to keep the aircraft in the air. By the time the first hook-up occurred, both the F-4E and KC-135 were flying below an altitude of 7,000 feet.

Whereas normal refueling airspeed is 315 knots, the refueling operation between the KC-135 and F-4E occurred below 200 knots. Both aircraft had to fly at high angle-of-attack to generate sufficient lift at this low airspeed. Boom Operator Simmons was faced with a particularly difficult challenge in that the failed starboard hydraulics of the F-4E caused it to yaw to the right. Nonetheless, he was able to make the hook-up with the F-4E refueling recepticle and transfer a bit of fuel to the ailing aircraft.

The transfer of fuel ceased during the first aerial refueling when the mechanical limits of the aircraft-to-aircraft connection were exceeded. The F-4E started to dive as it came off the refueling boom. At this critical juncture, Captain Goodman made the decision to follow the Phantom and get down in front of it for another go at aerial refueling. As the second fuel transfer operation began, the airspeed indicator registered 190 knots; barely above the KC-135’s landing speed.

While additional fuel was transferred to the F-4E, it was still not enough for it to make the divert airfield at Gander, New Foundland. The KC-135 performed two more risky aerial refuelings of the struggling Phantom. The last of which occurred at an altitude of only 1,600 feet above the ocean. At times during these harrowing operations, the KC-135 actually towed the F-4E on its refueling boom to help the latter gain altitude.

At length, the F-4E manged to climb to 6,000 feet and maintain 220 knots as its No. 1 engine began to cool. Able to fend for itself once again, the Phantom punched-off the KC-135 refueling boom. Goodman and crew continued to escort the F-4E to the now-close landing field at Gander, New Foundland. The Phantom pilot greased the landing much to the relief and joy of all.

For their heroic efforts on that eventful September day over the North Atlantic, the crew of the KC-135 received the USAF’s Mackay Trophy for the most meritorious flight of 1983.