Sixty-one years ago this week, USAF Major William F. “Pete” Knight made an emergency landing in X-15 No. 1 at Mud Lake, Nevada. Knight somehow managed to save the hypersonic aircraft following a complete loss of electrical power as the vehicle passed through 107,000 feet during the climb.

The famed X-15 Program conducted 199 flights between June 1959 and October 1968. North American Aviation (NAA) built three (3) X-15 aircraft. Twelve (12) men from NAA, USAF and NASA flew the X-15. Eight (8) pilots received astronaut wings for flying the X-15 beyond 250,000 feet. One (1) aircraft and one (1) pilot were lost during flight test.

The X-15 flew as fast as 4,520 mph (Mach 6.7) and as high as 354,200 feet. The basic airframe measured 50 feet in length, featured a wing span of 22 feet and had a gross weight of 33,000 pounds. The type’s Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine burned anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen to produce a sea level thrust of 57,000 pounds. The X-15 used both 3-axis aerodynamic and ballistic flight controls.

An X-15 mission was fast-paced. Flight time from B-52 drop to unpowered landing was typically 10 to 12 minutes in duration. The pilot wore a full pressure suit and experienced 6 to 7 G’s during pull-out from max altitude. There really was no such thing as a routine X-15 mission. However, all X-15 missions had one factor in common; high danger.

On Thursday, 29 June 1967, X-15 No. 1 (S/N 56-6670) made its 73rd and the X-15 Program’s 184th free flight. Launch took place at 1828 UTC as the NASA B-52B launch aircraft (S/N 52-0008) flew at Mach 0.82 and 40,000 feet near Smith Ranch, Nevada. Knight, making his 10th X-15 flight, quickly ignited the XLR-99 and started the climb upstairs.

The X-15 was performing well and Knight was enjoying the flight until 67.6 seconds into a planned 87 second XLR-99 burn. That’s when the engine suddenly quit. A couple of heartbeats later, the Stability Augmentation System (SAS) failed, the Auxiliary Power Units (APU’s) ceased operating, the X-15’s generators stopped functioning and the cockpit lights went out. This was the total hit; a complete power failure.

Pete Knight was now just along for the ride. No thrust to power the aircraft. No electrical power to run onboard systems. No hydraulics to move flight controls. Even the reaction controls appeared inoperative. The X-15 continued upward, but it wallowed aimlessly in the low dynamic pressure of high altitude flight. At this point, Knight considered taking his chances and punching-out.

The X-15 went over the top at 173,000 feet. On the way downhill, Knight was able to get some electrical power from the emergency battery. This meant that he now had some hydraulic power and could utilize the X-15’s flight control surfaces. Knight next tried to fire-up the APU’s. The right APU would not respond. The left APU fired, but the its generator would not engage.

As the X-15 descended and the dynamic pressure built-up, Knight was able to maneuver his stricken X-15. He headed for Mud Lake in a sustained 6-G turn. As he leveled off at 45,000 feet, Knight instinctively knew he could now make the east shore of the Nevada dry lake. But it was tough work to fly the X-15. Knight ended-up using both hands to fly the airplane; one hand on the side stick and one hand on the center stick.

While Knight was trying to get his airplane down on the ground in one piece, only he and his Maker knew his whereabouts. The X-15 flight test team certainly didn’t, since Knight’s radio, telemetry and radar transponder were now inop. Further, the X-15 was not being skinned tracked at the time of the electrical anomaly. Just before he touched-down at Mud Lake, Knight’s X-15 was spotted by NASA’s Bill Dana who was flying a F-104N chase aircraft.

Pete Knight made a good landing at Mud Lake. The X-15 slid to a stop. After a struggle with the release mechanism, he managed to get the canopy open. Hot and soaked with perspiration, Knight somehow removed his own helmet. A ground crewman usually did that for him. But there were no flight support people at his X-15 landing site on this day.

As he attempted to get out of the X-15 cockpit, Knight pulled an emergency release. To his surprise, the headrest blew off, bounced off the canopy and smacked him square in the head. Undeterred, Knight got out of the cockpit and onto terra firma. In the meantime, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules had landed at Mud Lake. Wearily, Pete Knight got onboard and returned to Edwards Air Force Base.

Post-flight investigation revealed that the most probable source of the X-15’s electrical failure was arcing in a flight experiment system. This system had been connected to the X-15’s primary electrical bus. The solution was to connect flight experiments to the secondary electrical bus.

Reflecting on Knight’s amazing recovery from almost certain disaster, long-time NASA flight test manager Paul Bickle claimed the fete was among the most impressive of the X-15 Program. Indeed, it was Pete Knight’s clearly uncommon piloting skill and calmness under pressure that gave him the edge.

Sixty-one years ago this month, USAF Captain Joseph W. Kittinger successfully completed the first Manhigh aero medical research balloon mission. During his 6.5-hour flight, Kittinger reached an altitude of 95,200 feet above mean sea level.

Project Manhigh was a United States Air Force biomedical research program that investigated the human factors of spaceflight by taking men into a near-space environment. Preparations for the trio of Manhigh flights began in 1955. The experience and data gleaned from Manhigh were instrumental to the success of the nation’s early manned spaceflight effort.

The Manhigh target altitude was approximately 100,000 feet above sea level. A helium-filled polyethylene balloon, just 0.0015-inches thick and inflatable to a maximum volume of over 3-million cubic feet, carried the Manhigh gondola into the earth’s stratosphere. At float altitude, this balloon expanded to a diameter of roughly 200 feet.

The Manhigh gondola was a hemispherically-capped cylinder that measured 3-feet in diameter and 8-feet in length. It was attached to the transporting balloon via a 40-foot diameter recovery parachute. Although compact, the gondola was amply provisioned with the necessities of flight including life support, power and communication systems. It also included expendable ballast for use in controlling the altitude of the Manhigh balloon.

The Manhigh test pilot wore a T-1 partial pressure suit during the mission. The garment provided protection in the event that the gondola cabin lost pressure at extreme altitude. The pilot was connected to a variety of sensors which transmitted his biomedical information to the ground throughout flight. This allowed medicos on the ground to keep a constant tab on the pilot’s physical status.

The flight of Manhigh I took place on Sunday, 02 June 1957 with USAF Captain Joseph W. Kittinger as pilot. The massive balloon carrying Kittinger and his gondola was released at 11:23 UTC from Fleming Field Airport, South Saint Paul, Minnesota. In less than 2 hours, Kittinger’s huge balloon reached its design float altitude of 95,200 feet above sea level.

Radio communication problems complicated the Manhigh I mission. While Kittinger could hear the ground, the ground could not hear him. However, the resourceful pilot managed to work around this issue by communicating with the ground via Morse code.

Though balloon, gondola and pilot were functioning quite well, the Manhigh I mission had to be cut short due to rapid depletion of the gondala’s oxygen supply. Post-flight investigation revealed that this anomaly was caused by accidental crossing of the oxygen supply and vent lines prior to the flight.

Kittinger made a safe and uneventful landing near Indian Creek, Minnesota; located roughly 60 nm southeast of the launch site. The recovery crew was quick to the scene and extracted the plucky pilot from the sealed balloon gondola which had fallen over on its side. The official mission elapsed time (MET) was recorded as 6 hours and 32 minutes.

The flight of Manhigh I was a significant technical accomplishment that materially contributed to the advancement of manned spaceflight. Indeed, a TIME Magazine article, entitled “Prelude to Space” and dated 17 June 1957, captured the essence of the achievement. A man had been subjected to space-equivalent physiological conditions for a protracted period, had functioned well in that environment, and then returned safely to earth without ill effect.

For his significant efforts during the Manhigh I mission, Captain Joseph W. Kittinger received the USAF Distinguished Flying Cross.

Fifty-two years ago this month, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Bartsow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

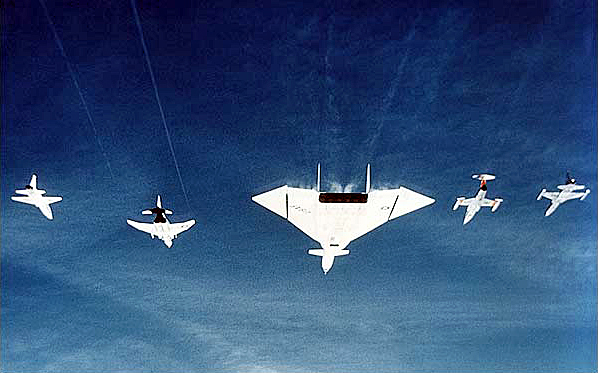

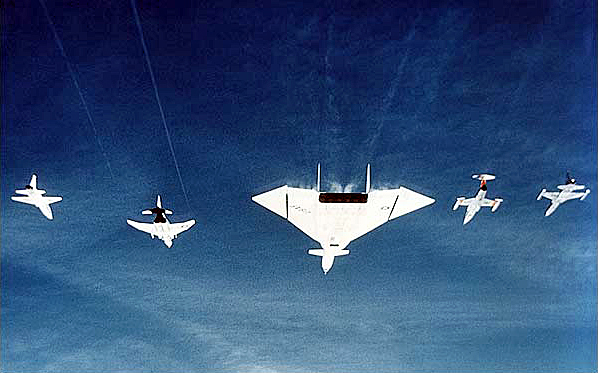

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Fifty-three years ago this week, Gemini Astronaut Edward H. White II became the first American to perform what in NASA parlance is referred to as an Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA). In everyday terms, we simply call it a “spacewalk”.

White, Mission Commander James A. McDivitt and their Gemini spacecraft were launched into low Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. The Gemini-Titan IV (GT-4) mission clock started at 15:15:59 UTC on Thursday, 03 June 1965.

On the third orbit, less than five hours after launch, White opened the Gemini IV starboard hatch. He stood in his seat and mounted a camera to capture his historic space stroll. He then cast-off from Gemini IV and became a human satellite.

White was tethered to Gemini IV via a 15-foot umbilical that provided oxygen and communications to his EVA suit. A gold-plated visor on his helmet protected his eyes from the searing glare of the sun. The spacewalking astronaut was also outfitted with a hand-held maneuvering unit that used compressed oxygen to power its small thrusters. And, like any good tourist, White also took along a camera to photograph the event.

Ed White had the time of his all-too-brief life in the 22 minutes that he walked in space. The sight of the earth, the spacecraft, the sun, the vastness of space, the freedom of movement all combined to make him excitedly exclaim at one point, “I feel like a million dollars!”.

Presently, it was time to get back into the spacecraft. But, couldn’t he just stay outside a little longer? NASA Mission Control and Commander McDivitt were firm. It was time to get back in; now! He grudgingly complied with the request/order, plaintively lamenting: “It’s the saddest moment of my life!”

As Ed White got back into his seat, he and McDivitt struggled to lock the starboard hatch. Both men were exhausted, but ebullient as they mused about the successful completion of America’s first space walk.

Gemini IV would eventually orbit the Earth 62 times before splashing-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 17:12:11 GMT on Sunday, 07 June 1965. The 4-day mission was another milestone in America’s quest for the moon.

The mission was over and yet Ed White was still a little tired. But then, that was really quite easy to understand. In the time that he was spacewalking outside the spacecraft, Gemini IV had traveled almost a third of the way around the Earth.