Fifty-one years ago this month, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Bartsow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

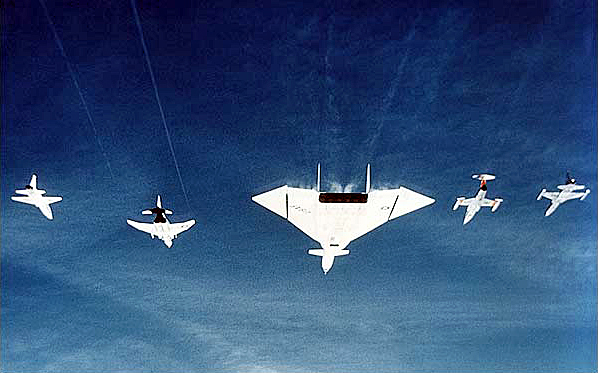

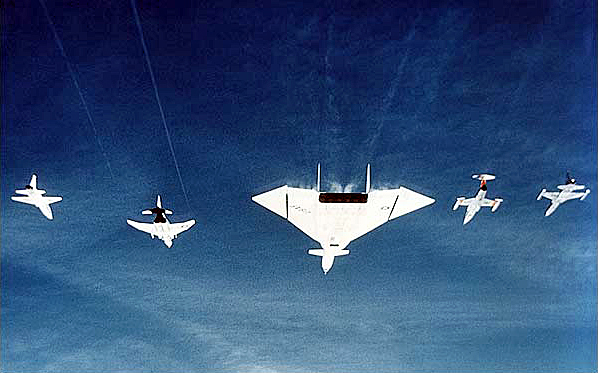

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Thirteen years ago today, Scaled Composite’s SpaceShipOne flew to an altitude of 62.214 statute miles. The flight marked the first time that a privately-developed flight vehicle had flown above the 62-statute mile boundary that entitles the flight crew to FAI-certified astronaut wings. As a result, SpaceShipOne pilot Mike Melvill became history’s first private citizen astronaut.

SpaceShipOne Mission 15P began with departure from California’s Mojave Spaceport at 0647 PDT. Carrying SpaceShipOne at the centerline station, Scaled’s White Knight launch aircraft climbed to the drop altitude of 47,000 feet.

At 0750 PDT on Monday, 21 June 2004, the 7,900-pound SpaceShipOne fell away from the White Knight and Melvill immediately ignited the 16,650-pound thrust hybrid rocket motor. Melvill then quickly pulled SpaceShipOne into a steep vertical climb.

Passing through 60,000 feet, SpaceShipOne experienced a series of uncommanded rolls as it encountered a wind shear. Melvill struggled with the controls in an attempt to arrest the roll transient. Then, late in the boost, the vehicle lost primary pitch trim control. In response, Melvill switched to the back-up system as he continued the ascent.

Rocket motor burnout occurred at 180,000 feet with SpaceShipOne traveling at 2,150 mph. It now weighed only 2,600 pounds. The vehicle then coasted to an apogee of 62.214 statute miles (328,490 feet). The target maximum altitude was 68.182 statute miles (360,000 feet). However, the control problems encountered going upstairs caused the trajectory to veer somewhat from the vertical.

Melvill experienced approximately 3.5 minutes of zero-g flight going over the top. He had some fun during this period as he released a bunch of M&M’s and watched the chocolate candy pieces float in the SpaceShipOne cabin.

Back to business now, Melvill transitioned SpaceShipOne to the high-drag feathered configuration in preparation for the critical entry phase of the mission. The vehicle initially accelerated to over 2,100 mph in the airless void before encountering the sensible atmosphere. At one point during atmospheric entry, Melvill experienced in excess of 5 g’s deceleration.

At 57,000 feet, Melvill reconfigured SpaceShipOne to the standard aircraft configuration for powerless flight back to the Mojave Spaceport. Fortunately, the aircraft was a very good glider. The control problems encountered during the vehicle’s ascent resulted in atmospheric entry taking place some 22 statute miles south of the targeted reentry point.

SpaceShipOne touched-down on Mojave Runway 12/30 at 0814 PDT; thus ending an historic, if not harrowing mission.

After the flight, Mike Melvill had much to say. But perhaps the following quote says it best for the rest of us who can only imagine what it was like: “And it was really an awesome sight, I mean it was like nothing I’ve ever seen before. And it blew me away, it really did. … You really do feel like you can reach out and touch the face of God, believe me.”

Fifty-nine years ago this month, the USN/Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III interceptor prototype took off on its maiden test flight at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Vought chief test pilot John W. Konrad was at the controls of the advanced high performance aircraft.

The Vought XF8U-3 was designed to intercept and defeat adversary aircraft. Although it bore a close external resemblance to its F8U-1 and F8U-2 forbears, the XF8U-3 was much more than just a block improvement in the Crusader line. It was considerably bigger, faster, and more capable than previous Crusaders and was in reality a new airplane.

The XF8U-3 measured 58.67 feet in length and had a wing span of an inch less than 40 feet. Gross Take-Off and empty weights tipped the scales at 38,770 lbs and 21,860 lbs, respectively. Power was provided by a single Pratt and Whitney J75-P-5A generating 29,500 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner.

A distinctive feature of the XF8U-3 was a pair of ventrally-mounted vertical tails. These surfaces were installed to improve aircraft directional stability at high Mach number. Retracted for take-off and landing, the surfaces were deployed once the aircraft was in flight.

The No. 1 XF8U-3 (S/N 146340) first flew on Monday, 02 June 1958 at Edwards Air Force, California. Vought chief test pilot John W. Konrad did the first flight piloting honors. The aircraft flew well with no major discrepancies reported. Approach and landing back at Edwards were uneventful.

Subsequent flight testing verified that the XF8U-3 was indeed a hot airplane. The type reached a top speed of Mach 2.39 and could have flown faster had its canopy had been designed for higher temperatures. The flight test-determined absolute altitude of 65 KFT was exceeded by 25 KFT in a zoom climb.

Those who flew the XF8U-3 said that the aircraft was a real thrill to fly. The Crusader III displayed outstanding acceleration, maneuverability and high-speed flight stability. Control harmony in pitch, yaw, and roll was extremely good as well.

Despite its great promise, the XF8U-3 never proceeded to production. This was primarily the result of coming up short in a head-to-head competition with the McDonnell F4H-1 Phantom II during the second half of 1958. While the Crusader was faster and more maneuverable than the Phantom, the latter’s mission capability and payload capacity were better.

Most historical records indicate that a total of five (5) Crusader III airframes were built. The serial numbers assigned by the Navy were 146340, 146341, 147085, 147086, and 147087. None of these aircraft exist today.

Fifty-two years ago this month, Gemini Astronaut Edward H. White II became the first American to perform what in NASA parlance is referred to as an Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA). In everyday terms, we simply call it a “spacewalk”.

White, Mission Commander James A. McDivitt and their Gemini spacecraft were launched into low Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. The Gemini-Titan IV (GT-4) mission clock started at 15:15:59 UTC on Thursday, 03 June 1965.

On the third orbit, less than five hours after launch, White opened the Gemini IV starboard hatch. He stood in his seat and mounted a camera to capture his historic space stroll. He then cast-off from Gemini IV and became a human satellite.

White was tethered to Gemini IV via a 15-foot umbilical that provided oxygen and communications to his EVA suit. A gold-plated visor on his helmet protected his eyes from the searing glare of the sun. The spacewalking astronaut was also outfitted with a hand-held maneuvering unit that used compressed oxygen to power its small thrusters. And, like any good tourist, White also took along a camera to photograph the event.

Ed White had the time of his all-too-brief life in the 22 minutes that he walked in space. The sight of the earth, the spacecraft, the sun, the vastness of space, the freedom of movement all combined to make him excitedly exclaim at one point, “I feel like a million dollars!”.

Presently, it was time to get back into the spacecraft. But, couldn’t he just stay outside a little longer? NASA Mission Control and Commander McDivitt were firm. It was time to get back in; now! He grudgingly complied with the request/order, plaintively lamenting: “It’s the saddest moment of my life!”

As Ed White got back into his seat, he and McDivitt struggled to lock the starboard hatch. Both men were exhausted, but ebullient as they mused about the successful completion of America’s first space walk.

Gemini IV would eventually orbit the Earth 62 times before splashing-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 17:12:11 GMT on Sunday, 07 June 1965. The 4-day mission was another milestone in America’s quest for the moon.

The mission was over and yet Ed White was still a little tired. But then, that was really quite easy to understand. In the time that he was spacewalking outside the spacecraft, Gemini IV had traveled almost a third of the way around the Earth.