Nineteen years ago this month, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor caused the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit paydirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s historic scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and its crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

Fifty-five years ago this month, Gemini Astronaut Edward H. White II became the first American to perform what in NASA parlance is referred to as an Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA). In everyday terms, it is referred to as a “spacewalk”.

White, Mission Commander James A. McDivitt and their Gemini spacecraft were launched into low Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. The Gemini-Titan IV (GT-4) mission clock started at 15:15:59 UTC on Thursday, 03 June 1965.

On the third orbit, less than five hours after launch, White opened the Gemini IV starboard hatch. He stood in his seat and mounted a camera to capture his historic space stroll. He then cast-off from Gemini IV and became a human satellite.

White was tethered to Gemini IV via a 15-foot umbilical that provided oxygen and communications to his EVA suit. A gold-plated visor on his helmet protected his eyes from the searing glare of the sun. The spacewalking astronaut was also outfitted with a hand-held maneuvering unit that used compressed oxygen to power its small thrusters. And, like any good tourist, White also took along a camera to photograph the event.

Ed White had the time of his all-too-brief life in the 22 minutes that he walked in space. The sight of the earth, the spacecraft, the sun, the vastness of space, the freedom of movement all combined to make him excitedly exclaim at one point, “I feel like a million dollars!”.

Presently, it was time to get back into the spacecraft. But, couldn’t he just stay outside a little longer? NASA Mission Control and Commander McDivitt were firm. It was time to get back in; now! He grudgingly complied with the request/order, plaintively lamenting: “It’s the saddest moment of my life!”

As Ed White got back into his seat, he and McDivitt struggled to lock the starboard hatch. Both men were exhausted, but ebullient as they mused about the successful completion of America’s first space walk.

Gemini IV would eventually orbit the Earth 62 times before splashing-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 17:12:11 GMT on Sunday, 07 June 1965. The 4-day mission was another milestone in America’s quest for the moon.

The mission was over and yet Ed White was still a little tired. But then, that was really quite easy to understand. In the time that he was spacewalking outside the spacecraft, Gemini IV had traveled almost a third of the way around the Earth.

Fifty-four years ago today, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Barstow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

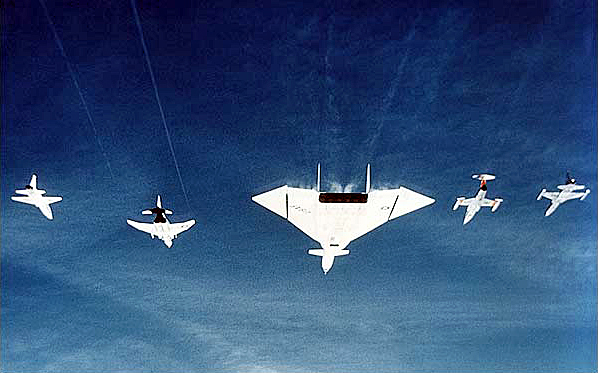

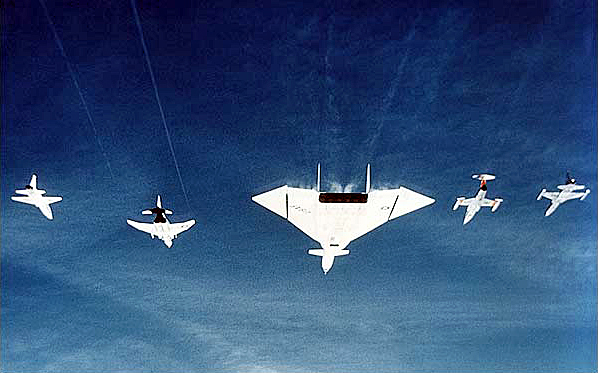

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Nineteen years ago today, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet (Supersonic Combustion RAMJET) propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor or so-called “smoking gun” cause was responsible for the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit pay dirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the pioneering scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s history-making scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and her crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.