Sixty-four years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, triumph quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 mothership at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the descending unit and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, such was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded that mark in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

Nineteen years ago this month, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor caused the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit paydirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s historic scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and its crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

Fifty-four years ago today, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Barstow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

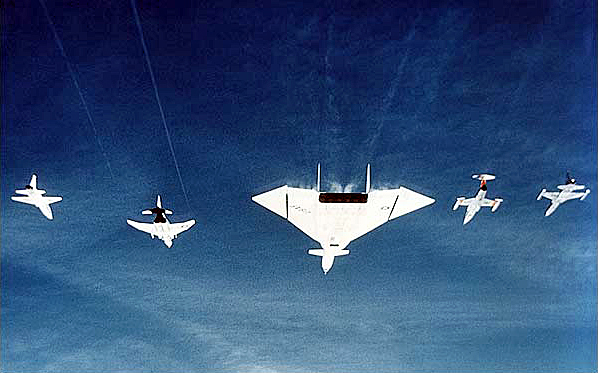

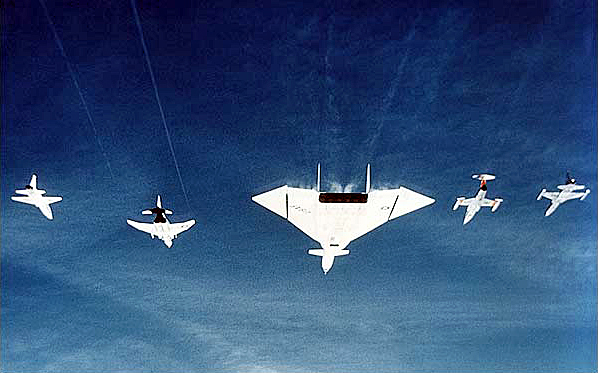

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Nineteen years ago today, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet (Supersonic Combustion RAMJET) propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor or so-called “smoking gun” cause was responsible for the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit pay dirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the pioneering scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s history-making scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and her crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

Seventy-seven years ago this month, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most intriguing and haunting stories in the annals of aviation. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

Sixty-four years ago this month, the lone remaining USAF/Martin XB-51 light attack bomber prototype crashed during take-off from El Paso International Airport in Texas. The cause of the mishap was attributed to premature rotation of the aircraft leading to an unrecoverable stall.

A product of the post-WWII 1940’s, the Martin XB-51 was envisioned as a jet-powered replacement for the piston-driven Douglas A-26 Invader. The swept-wing XB-51 utilized a unique propulsion system which consisted of a trio of General Electric J47 turbojets. Demonstrated top speed was 560 knots at sea level.

The XB-51 was a good-sized airplane. With a length of 85 feet and a wing span of 53 feet, the XB-51 had a nominal take-off weight of around 56,000 lbs. The wings were swept 35 degrees aft and incorporated 6 degrees of anhedral. The latter feature to counter the large dihedral effect produced by the type’s tee-tail.

A pair of XB-51 aircraft were built by Martin for USAF. Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-0685) first took to the air in October of 1949 followed by the flight debut of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) in April of 1950. The air crew consisted of a pilot who sat underneath a large, clear canopy and a navigator housed within the fuselage.

While the XB-51 flew hundreds of hours in flight test and made many lasting contributions to the aviation field, the aircraft never went into production. This fate was primarily the result of having lost a head-to-head competitive fly-off against the English Electric Canberra B-57A light attack bomber in 1951.

The No. 1 XB-51 aircraft was lost on Sunday, 25 March 1956 during take-off from El Paso International Airport. The mishap aircraft accelerated more slowly than normal and with the end of the runway coming up quickly, the pilot rotated the aircraft in a attempt to get airborne. Unfortunately, the rotation was premature and the wing stalled. The aircraft exploded on impact and the crew of USAF Major James O. Rudolph and Staff-Sargent Wilbur R. Savage were killed.

The loss of the No. 1 XB-51 was preceded by the destruction of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) on Friday, 09 May 1952. That tragedy occurred during low-altitude aerobatic maneuvers at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The pilot, USAF Major Neil H. Lathrop, perished in the resulting post-impact explosion and inferno.

As a footnote, the XB-51 was never assigned an official nickname by the Air Force. However, it was unofficially referred to in some aviation circles as the Panther. Due to its prominently-long fuselage, the less majestic monicker of “Flying Cigar” was sometimes used as well.

Sixty-five years ago today, North American test pilot George F. Smith became the first man to survive a high dynamic pressure ejection from an aircraft in supersonic flight. Smith ejected from his F-100A Super Sabre at 777 MPH (Mach 1.05) as the crippled aircraft passed through 6,500 feet in a near-vertical dive.

On the morning of Saturday, 26 February 1955, North American Aviation (NAA) test pilot George F. Smith stopped by the company’s plant at Los Angeles International Airport to submit some test reports. Returning to his car, he was abruptly hailed by the company dispatcher. A brand-new F-100A Super Sabre needed to be test flown prior to its delivery to the Air Force. Would Mr. Smith mind doing the honors?

Replying in the affirmative, Smith quickly donned a company flight suit over his street clothes, got the rest of his flight gear and pre-flighted the F-100A Super Sabre (S/N 53-1659). After strapping into the big jet, Smith went through the normal sequence of aircraft pre-launch flight control and system checks. While the control column did seem a bit stiff in pitch, Smith nonetheless decided that his aerial steed was ready for flight.

Smith executed a full afterburner take-off to the west. The fleet Super Sabre eagerly took to the air. Accelerating and climbing, the aircraft was almost supersonic as it passed through 35,000 feet. Peaking out around 37,000 feet, Smith sensed a heaviness in the flight control column. Something wasn’t quite right. The jet was decidedly nose heavy. Smith countered by pulling aft stick.

The Super Sabre did not respond at all to Smith’s control inputs. Instead, it continued an un-commanded dive. Shallow at first, the dive steepened even as the 215-lb pilot pulled back on the stick with all of his might. But all to no avail. The jet’s hydraulic system had failed. As the stricken aircraft now accelerated toward the ground, Smith rightly concluded that this was going to be a short ride.

George Smith knew that he had only one alternative now; Eject. However, he also knew that the chances were quite small that he would survive what was quickly shaping-up to be a quasi-supersonic ejection. Suddenly, over the radio, Smith heard another Super Sabre pilot flying in his vicinity frantically yell: “Bail out, George!” So exhorted, the test pilot complied.

Smith jettisoned his canopy. The roar from the air-stream around him was unlike anything he had ever heard. Almost paralyzed with fear, Smith reflexively hunkered-down in the cockpit. The exact wrong thing to do. His head needed to be positioned up against the seat’s headrest and his feet placed within retraining stirrups prior to ejection. But there was no time for any of that now. Smith pulled the ejection seat trigger.

George Smith’s last recollection of his nightmare ride was that the Mach Meter read 1.05; 777 mph at the ejection altitude of 6,500 feet above the Pacific Ocean. These flight conditions corresponded to a dynamic pressure of 1,240 pounds per square foot. As he was fired out of the cockpit and into the harsh air-stream, Smith’s body was subjected to an astounding drag force of around 8,000 lbs producing on the order of 40-g’s of deceleration.

Mercifully, Smith did not recall what came next. The ferocious wind blast stripped him of his helmet, oxygen mask, footwear, flight gloves, wrist watch and even his ring. Blood was forced into his head which became grotesquely swollen and his facial features unrecognizable. His eyelids fluttered and his eyes were tortuously mauled by the aerodynamic and inertial load of his ejection. Smith’s internal organs, most especially his liver, were severely damaged. His body was horribly bruised and beaten as it flailed end-over-over end uncontrollably.

Smith and his seat parted company as programmed followed by automatic deployment of his parachute. The opening forces were so high that a third of the parachute material was ripped away. Thankfully, the remaining portion held together and the unconscious Smith landed about 75 yards away from a fishing vessel positioned about a half-mile form shore. Providentially, the boat’s skipper was a former Navy rescue expert. Within a minute of hitting the water, Smith was rescued and brought onboard.

George Smith was hovering near death when he arrived at the hospital. In severe shock and with only a faint pulse, doctors quickly went to work. Smith awoke on his sixth day of hospitalization. He could hear, but he couldn’t see. His eyes had sustained multiple subconjunctival hemorrhages and the prevailing thought at the time was that he would never see again.

Happily, George Smith did recover almost fully from his supersonic ejection experience. He spent seven (7) months in the hospital and endured several operations. During that time, Smith’s weight dropped to 150 lbs. He was left with a permanently damaged liver to the extent that he could no longer drink alcohol. As for Smith’s vision, it returned to normal. However, his eyes were ever after somewhat glare-sensitive and slow to adapt to darkness.

Not only did George Smith return to good health, he also got back in the cockpit. First, he was cleared to fly low and slow prop-driven aircraft. Ultimately, he got back into jets, including the F-100A Super Sabre. Much was learned about how to markedly improve high speed ejection survivability in the aftermath of Smith’s supersonic nightmare. He in essence paid the price so that others would fare better in such circumstances as he endured.

It is possible that George Smith was not the first pilot to eject supersonically. USN LCdr Authur Ray Hawkins survived ejection from his stricken Grumman F9F-6 Cougar in 1953. Aircraft speed at ejection was never definitively determined, but was estimated to be between 688 (Mach 0.99) and 782 mph (Mach 1.16). In any event, the dynamic pressure and therefore the airloads associated with Hawkins ejection were less than half that of Smith’s punch-out.

George Smith was thirty-one (31) at the time of his F-100A mishap. He lived a happy and productive thirty-nine (39) more years after its occurrence. Smith passed from this earthly scene in 1994.

Fifty-three years ago this month the Apollo 204 prime crew perished as fire swept through their Apollo Block I Command Module (CM). The Apollo 204 crew of Command Pilot Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White II and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee had been scheduled to make the first manned flight of the Apollo Program some three weeks hence.

On Friday, 27 January 1967, during a plugs-out ground test on LC-34 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, a fire broke out in the Apollo 204 spacecraft at 23:31:04 UTC (6:31:04 pm EST). Shortly after, a chilling cry was heard across the communications network from Astronaut Chaffee: “We’ve got a fire in the cockpit”.

Believed to have started just below Grissom’s seat, the fire quickly erupted into an inferno that claimed the men’s lives in less than 30 seconds. While each received extensive 3rd degree burns, death was attributed to toxic smoke inhalation.

The Apollo 204 fire was most likely brought about by some minor malfunction or failure in equipment or wire insulation. This failure, which was never positively identified, initiated a sequence of events that culminated in the conflagration.

The post-mishap investigation uncovered numerous defects in CM Block I design, manufacturing, and workmanship. The use of a (1) pure oxygen atmosphere pressurized to 16.7 psia and (2) complex 3-component hatch design (that took a minimum of 90 seconds to open) sealed the astronauts’ fate.

A haunting irony of the tragedy is that America lost her first astronaut crew, not in the sideral heavens, but in a spacecraft that was firmly rooted to the ground.

Thirty-four years ago this month, the seven member crew of STS-51L perished when the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch from LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The tragedy was the first fatal in-flight mishap in the history of American manned spaceflight.

In remarks made at a memorial service held for the Challenger Seven in Houston, Texas on Friday, 31 January 1986, President Ronald Wilson Reagan expressed the following sentiments:

“The future is not free: the story of all human progress is one of a struggle against all odds. We learned again that this America, which Abraham Lincoln called the last, best hope of man on Earth, was built on heroism and noble sacrifice. It was built by men and women like our seven star voyagers, who answered a call beyond duty, who gave more than was expected or required and who gave it little thought of worldly reward.”

We take this opportunity to remember the noble fallen:

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, Commander

Michael John Smith, Pilot

Ellison S. Onizuka, Mission Specialist One

Judith Arlene Resnik, Mission Specialist Two

Ronald Erwin McNair, Mission Specialist Three

S.Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist One

Gregory Bruce Jarvis, Payload Specialist Two

Speaking for grieving families and countrymen, President Reagan closed his eulogy with these words:

“Dick, Mike, Judy, El, Ron, Greg and Christa – your families and your country mourn your passing. We bid you goodbye. We will never forget you. For those who knew you well and loved you, the pain will be deep and enduring. A nation, too, will long feel the loss of her seven sons and daughters, her seven good friends. We can find consolation only in faith, for we know in our hearts that you who flew so high and so proud now make your home beyond the stars, safe in God’s promise of eternal life.”

Fifty-six years ago to the day, USAF NF-104A (S/N 56-762; Ship 3) crashed to destruction following a rocket-powered zoom to 101,600 feet above mean sea level (AMSL). The pilot, USAF Colonel Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager, was seriously injured, but survived when he successfully ejected from the stricken aircraft approximately 5,000 feet above ground level (AGL).

The USAF/Lockheed NF-104A was designed to provide spaceflight-like training experience for test pilots attending the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS) at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The type was a modification of the basic F-104A Starfighter aircraft. Three copies of the NF-104A were produced (S/N’s 56-0756, 56-0760 and 56-0762). It was the ultimate zoom flight platform.

In addition to a stock General Electric J79-GE-3 turbojet, the NF-104A was powered by a Rocketdyne LR121-NA-1 rocket motor. The J79 generated 15,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner and burned JP-4. The LR-121 produced 6,000 pounds of thrust and burned a combination of JP-4 and 90% hydrogen peroxide. Rocket motor burn time was on the order of 90 seconds.

Around 1400 hours PST on Tuesday, 10 December 1963, Colonel Yeager took-off from Edwards Air Force Base to attempt his second zoom flight of the day. That morning, he had zoomed NF-104A, S/N 56-760 to an altitude of 108,700 feet. Four days earlier, Yeager had zoomed the same airplane to the highest altitude he would ever achieve in the type; 110,500 feet AMSL.

The zoom apex altitude for the ill-fated afternoon flight was only 101,600 feet AMSL with rocket motor burnout taking place 5 seconds post-apogee. That is, the aircraft was already on the descending leg of the zoom trajectory and in the early stages of reentry. Yeager later reported that the aircraft angle-of-attack at that point was on the order of 50 deg; a figure that is well past the NF-104A pitch-up angle-of-attack (i.e., 14-17 deg). Yeager had flown the aircraft this way on previous zoom flights and had always been able to lower the nose via reaction control system (RCS) inputs.

Unfortunately, the RCS did not not have sufficient pitch control authority to bring the nose down on the mishap flight. As a result, the aircraft began the reentry in an extremely nose-high attitude. As the dynamic pressure rapidly built-up, the NF-104A departed controlled flight and went through a series of post-stall gyrations between 90,000 and 65,000 feet. These gyrations ultimately led to a series of flat spins occurring between 65,000 and 20,000 feet.

Running out of altitude, Yeager desperately deployed his drag parachute as an anti-spin device. This action indeed stopped the flat spin. Airspeed picked-up to 180 KIAS with the aircraft hanging in the chute, but the pilot was unable to get an air-start on his J79 turbojet which had spooled down to 6% of maximum RPM. At 12,000 feet, Yeager jettisoned his drag chute and the NF-104A immediately pitched-up again into a flat spin. After three-quarters of a turn, Yeager ejected about 5,000 feet AGL. Yeager landed close to where the mishap aircraft had impacted and was in a great deal of pain due to burns he received during the ejection process. Happily, he survived this traumatic event and recovered completely from his injuries.

Objective analysis of the loss of NF-104A, S/N 56-762 reveals that the aircraft simply was not flown in a manner commensurate with the intricacies of the zoom environment. The critical importance of quickly intercepting and maintaining the target inertial pitch angle during pull-up had been repeatedly demonstrated by other test pilots as had proper control of aircraft angle-of-attack during reentry. Colonel Yeager elected not to fly the aircraft in accordance with these dictates.

In all of his NF-104A zoom attempts, Colonel Yeager consistently flew the airplane over the top at angles-of-attack well beyond the pitch-up value. RCS control authority was sufficient to lower the nose to sub-pitch-up angles-of-attack just prior to reentry on all but the mishap flight. Unfortunately, the low apex altitude (101,600 feet AMSL) of that zoom resulted in a higher dynamic pressure that, in conjunction with very high angles-of-attack, produced a nose-up aerodynamic pitching moment that the RCS could not overcome.

The aircraft mishap of 10 December 1963 forever changed the way in which NF-104A pilots would be allowed to fly the rocket-powered zoom mission. Prior to the mishap, the NF-104A had been zoomed to an altitude of 120,800 feet AMSL by USAF Major Robert W. Smith on 06 December 1963. This unofficial United States record still stands today. After a mishap investigation, NF-104A maximum altitude was limited to 108,000 feet AMSL. This restricted performance was mandated ostensibly out of concern for the safety of ARPS student test pilots.

The ultimate and lasting result of the post-mishap restriction on NF-104A flight performance was that it did a great disservice to ARPS student test pilots in that it made their spaceflight training experience something less than what it could and should have been. It is ironic that, although the correct manner in which to zoom the airplane had been repeatedly validated by USAF and Lockheed test pilots prior to the 56-0762 mishap, the decision to restrict NF-104A performance was based on a single flight which clearly demonstrated how not to fly the airplane.