Fifty-two years ago this month, the No. 3 USAF/North American X-15 research aircraft broke-up during a steep dive from an apogee of 266,000 feet. The pilot, USAF Major Michael J. Adams, perished when his aircraft was ripped apart by aerodynamic forces as it passed through 65,000 feet at more than 2,500 mph.

The hypersonic X-15 was arguably the most productive X-Plane of all time. Between 1959 and 1968, a trio of X-15 aircraft were flown by a dozen pilots for a total of 199 official flight research missions. Along the way, the fabled X-15 established manned aircraft records for speed (4,534 mph; Mach 6.72) and altitude (354,200 feet).

The X-15 was a rocket, aircraft and spacecraft all rolled into one. Burning anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen, its XLR-99 rocket engine generated 57,000 lbs of sea level thrust. Reaction controls were required for flight in vacuum. Each flight also required careful management of aircraft energy state to ensure a successful, one attempt only, unpowered landing.

On Wednesday, 15 November 1967, the No. 3 X-15 (S/N 56-6672) made the 191st flight of the X-15 Program. In the cockpit was USAF Major Michael J. Adams making his 7th flight in the X-15. He had been flying the aircraft since October of 1966. Like all X-15 pilots, he was a skilled, accomplished test pilot used to dealing with the demands and high risk of flight research work.

X-15 Ship No. 3 was launched from its B-52B (S/N 52-0008) mothership over Nevada’s Delamar Dry Lake at 18:30 UTC. As the X-15 fell away from the launch aircraft at Mach 0.82 and 45,000 feet, Adams fired the XLR-99 and started uphill along a trajectory that was supposed to top-out around 250,000 feet. If all went well, Adams would land on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base in California roughly 10 minutes later.

Around 85,000 on the way upstairs, Adams became distracted when an electrical disturbance from an onboard flight experiment adversely affected the X-15’s flight control system, flight computer and inertial reference system. As a result, data on several key cockpit displays became corrupted. Though with some difficulty, Adams pressed-on with the flight which peaked-out around 266,000 feet approximately three (3) minutes from launch.

As a result of degraded flight systems and perhaps disoriented by vertigo, Mike Adams soon discovered that his aircraft was veering from the intended heading. He indicated to the control room at Edwards that his steed was not controlling correctly. Passing through 230,000 feet, Adams cryptically radioed that he was in a Mach 5 spin. Mission control was stunned. There was nothing in the X-15 flight manual that even addressed such a possibility.

Incredibly, Mike Adams somehow managed to recover from his hypersonic spin as the X-15 passed through 118,000 feet. However, the aircraft was inverted and in a 45-degree dive at Mach 4.7. Still, Adams may very well have recovered from this precarious flight state but for the appearance of another flight system problem just as he recovered the X-15 from its horrific spin.

X-15 Ship No. 3 was configured with a Minneapolis-Honeywell adaptive flight control system (AFCS). Known as the MH-96, the AFCS was supposed to help the pilot control the X-15 during high performance flight. Unfortunately, the unit entered a limit-cycle oscillation just after spin recovery and failed to change gains as the dynamic pressure rapidly increased during Ship No. 3’s final descent. This anomaly saturated the X-15 flight control system and effectively overrode manual inputs from the pilot.

The limit-cycle oscillation drove the X-15’s pitch rate to intolerably-high values in the face of rapidly increasing dynamic pressure. Passing through 65,000 feet at better than 2,500 mph (Mach 3.9), Ship No. 3 came apart northeast of Johannesburg, California. The main wreckage impacted just northwest of Cuddeback Dry Lake. Mike Adams had made his final flight.

For his flight to 266,000 feet, USAF Major Michael J. Adams was posthumously awarded Astronaut Wings by the United States Air Force. His name was included on the roll of the Astronaut Memorial at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in 1991. Finally, on Saturday, 08 May 2004, a small memorial was erected to the memory of Major Adams near his X-15 crash site situated roughly 39 miles northeast of Edwards Air Force Base.

Sixty-three years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, triumph quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 mothership at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the descending unit and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, such was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded that mark in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

Fifty-three years ago today, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Bartsow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

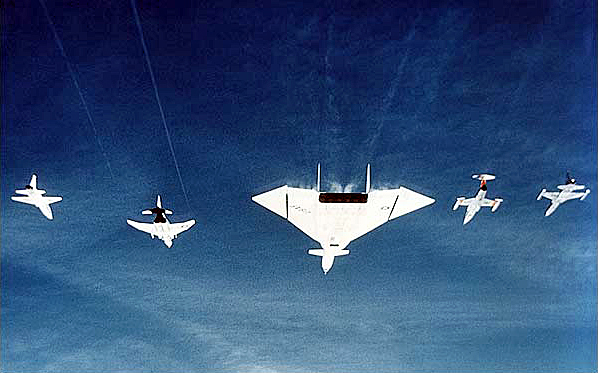

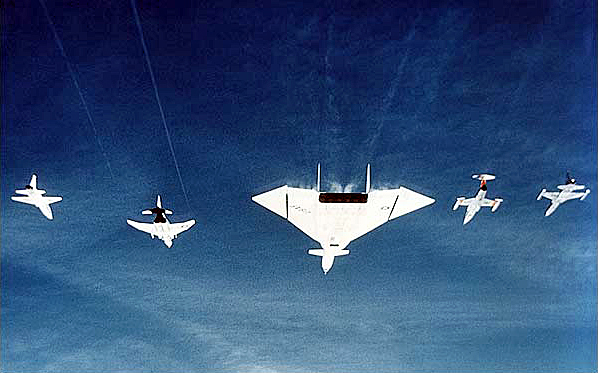

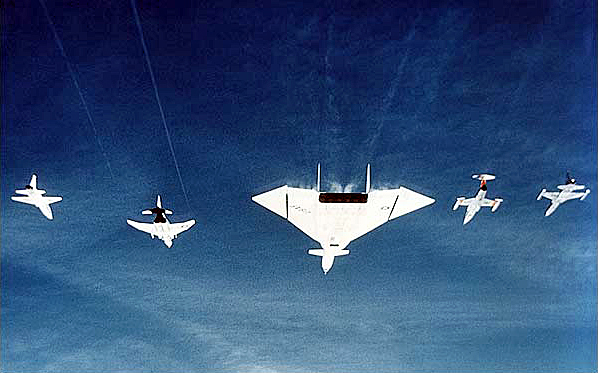

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Seventy-six years ago this week, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most haunting and intriguing stories in the annals of aviation history. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

Fifty-five years ago today, USAF NF-104A (S/N 56-762) crashed to destruction following a rocket-powered zoom to 101,600 feet above mean sea level (AMSL). The pilot, USAF Colonel Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager, was seriously injured, but survived when he successfully ejected from the stricken aircraft approximately 5,000 feet above ground level (AGL).

The USAF/Lockheed NF-104A was designed to provide spaceflight-like training experience for test pilots attending the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS) at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The type was a modification of the basic F-104A Starfighter aircraft. Three copies of the NF-104A were produced (S/N’s 56-0756, 56-0760 and 56-0762). It was the ultimate zoom flight platform.

In addition to a stock General Electric J79-GE-3 turbojet, the NF-104A was powered by a Rocketdyne LR121-NA-1 rocket motor. The J79 generated 15,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner and burned JP-4. The LR-121 produced 6,000 pounds of thrust and burned a combination of JP-4 and 90% hydrogen peroxide. Rocket motor burn time was on the order of 90 seconds.

Around 1400 hours PST on Tuesday, 10 December 1963, Colonel Yeager took-off from Edwards Air Force Base to attempt his second zoom flight of the day. That morning, he had zoomed NF-104A, S/N 56-760 to an altitude of 108,700 feet. Four days earlier, Yeager had zoomed the same airplane to the highest altitude he would ever achieve in the type; 110,500 feet AMSL.

The zoom apex altitude for the ill-fated afternoon flight was only 101,600 feet AMSL with rocket motor burnout taking place 5 seconds post-apogee. That is, the aircraft was already on the descending leg of the zoom trajectory and in the early stages of reentry. Yeager later reported that the aircraft angle-of-attack at that point was on the order of 50 deg; a figure that is well past the NF-104A pitch-up angle-of-attack (i.e., 14-17 deg). Yeager had flown the aircraft this way on previous zoom flights and had always been able to lower the nose via reaction control system (RCS) inputs.

Unfortunately, the RCS did not not have sufficient pitch control authority to bring the nose down on the mishap flight. As a result, the aircraft began the reentry in an extremely nose-high attitude. As the dynamic pressure rapidly built-up, the NF-104A departed controlled flight and went through a series of post-stall gyrations between 90,000 and 65,000 feet. These gyrations ultimately led to a series of flat spins occurring between 65,000 and 20,000 feet.

Running out of altitude, Yeager desperately deployed his drag parachute as an anti-spin device. This action indeed stopped the flat spin. Airspeed picked-up to 180 KIAS with the aircraft hanging in the chute, but the pilot was unable to get an airstart on his J79 turbojet which had spooled down to 6% of maximum RPM. At 12,000 feet, Yeager jettisoned his drag chute and the NF-104A immediately pitched-up again into a flat spin. After three-quarters of a turn, Yeager ejected about 5,000 feet AGL. Yeager landed close to where the mishap aircraft had impacted and was in a great deal of pain due to burns he received during the ejection process. Happily, he survived this traumatic event and recovered completely from his injuries.

Objective analysis of the loss of NF-104A, S/N 56-762 reveals that the aircraft simply was not flown in a manner commensurate with the intricacies of the zoom environment. The critical importance of quickly intercepting and maintaining the target inertial pitch angle during pull-up had been repeatedly demonstrated by other test pilots as had proper control of aircraft angle-of-attack during reentry. Colonel Yeager elected not to fly the aircraft in accordance with these dictates.

In all of his NF-104A zoom attempts, Colonel Yeager consistently flew the airplane over the top at angles-of-attack well beyond the pitch-up value. RCS control authority was sufficient to lower the nose to sub-pitch-up angles-of-attack just prior to reentry on all but the mishap flight. Unfortunately, the low apex altitude (101,600 feet AMSL) of that zoom resulted in a higher dynamic pressure that, in conjunction with very high angles-of-attack, produced a nose-up aerodynamic pitching moment that the RCS could not overcome.

The aircraft mishap of 10 December 1963 forever changed the way in which NF-104A pilots would be allowed to fly the rocket-powered zoom mission. Prior to the mishap, the NF-104A had been zoomed to an altitude of 120,800 feet AMSL by USAF Major Robert W. Smith on 06 December 1963. This unofficial United States record still stands today. After a mishap investigation, NF-104A maximum altitude was limited to 108,000 feet AMSL. This restricted performance was mandated ostensibly out of concern for the safety of ARPS student test pilots.

The ultimate and lasting result of the post-mishap restriction on NF-104A flight performance was that it did a great disservice to ARPS student test pilots in that it made their spaceflight training experience something less than what it could and should have been. It is ironic that, although the correct manner in which to zoom the airplane had been repeatedly validated by USAF and Lockheed test pilots prior to the 56-0762 mishap, the decision to restrict NF-104A performance was based on a single flight which clearly demonstrated how not to fly the airplane.

Sixty-two years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, triumph quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 mothership at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the descending unit and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, such was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded that mark in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

Fifty-seven years ago this month, Mercury Seven Astronaut Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Jr. became the second American to go into space. Grissom’s suborbital mission was flown aboard a Mercury space capsule that he named Liberty Bell 7.

The United States first manned space mission was flown on Friday, 05 May 1961. On that day, NASA Astronaut Alan B. Shepard, Jr. flew a 15-minute suborbital mission down the Eastern Test Range in his Freedom 7 Mercury spacecraft. Known as Mercury-Redstone 3, Shepard’s mission was entirely successful and served to ignite the American public’s interest in manned spaceflight.

Shepard was boosted into space via a single stage Redstone rocket. This vehicle was originally designed as an Intermediate-Range ballistic Missile (IRBM) by the United States Army. It was man-rated (that is, made safer and more reliable) by NASA for the Mercury suborbital mission. A descendant of the German V-2 missile, the Redstone produced 78,000 lbs of sea level thrust.

Shepard’s suborbital trajectory resulted in an apogee of 101 nautical miles (nm). With a burnout velocity of 7,541 ft/sec, Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 263 nm downrange of its LC-5 launch site at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Shepard endured a maximum deceleration of 11 g’s during the reentry phase of the flight.

Mercury-Redstone 4 was intended as a second and confirming test of the Mercury spacecraft’s space-worthiness. If successful, this mission would clear the way for pursuit and achievement of the Mercury Program’s true goal which was Earth-orbital flight. All of this rested on the shoulders of Gus Grissom as he prepared to be blasted into space.

Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft was a better ship than Shepard’s steed from several standpoints. Liberty Bell 7 was configured with a large centerline window rather than the two small viewing ports featured on Freedom 7. The vehicle’s manual flight controls included a new rate stabilization system. Grissom’s spacecraft also incorporated a new explosive hatch that made for easier release of this key piece of hardware.

Mercury-Redstone 4 (MR-4) was launched from LC-5 at Cape Canaveral on Friday, 21 July 1961. Lift-off time was 12:20:36 UTC. From a trajectory standpoint, Grissom’s flight was virtually the same as Shepard’s. He found the manual 3-axis flight controls to be rather sluggish. Spacecraft control was much improved when the new rate stabilization system was switched-on. The time for retro-fire came quickly. Grissom invoked the retro-fire sequence and Liberty Bell 7 headed back to Earth.

Liberty Bell 7’s reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere was conducted in a successful manner. The drogue came out at 21,000 feet to stabilize the spacecraft. Main parachute deployed occurred at 12,300 feet. With a touchdown velocity of 28 ft/sec, Grissom’s spacecraft splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 32 seconds after lift-off. America now had both a second spaceman and a second successful space mission under its belt.

Following splashdown, Grissom logged final switch settings in the spacecraft, stowed equipment and prepared for recovery as several Marine helicopters hovered nearby. As he did so, the craft’s new explosive hatch suddenly blew for no apparent reason. Water started to fill the cockpit and the surprised astronaut exited the spacecraft as quickly as possible.

Grissom found himself outside his psacecraft and in the water. He was horrfied to see that Liberty Bell 7 was in imminent peril of sinking. The primary helicopter made a valiant effort to hoist the spacecraft out of the water, but the load was too much for it. Faced with losing his vehicle and crew, the pilot elected to release Liberty Bell 7 and abandon it to a watery grave.

Meanwhile, Grissom struggled just to stay afloat in the churning ocean. The prop blast from the recovery helicopters made the going even tougher. Finally, Grissom was able to retrieve and get himself into a recovery sling provided by one of the helicopters. He was hoisted aboard and subsequently delivered safely to the USS Randolph.

In the aftermath of Mercury-Redstone 4, accusations swirled around Grissom that he had either intentionally or accidently hit the detonation plunger that activated the explosive hatch. Always the experts on everything, especially those things of which they have little comprehension, the root weevils of the press insinuated that Grissom must have panicked. Grissom steadfastly asserted to the day that he passed from this earthly scene that he did no such thing.

Liberty Bell 7 rested at a depth of 15,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean until it was recovered by a private enterprise on Tuesday, 20 July 1999; a day short of the 38th anniversary of Gus Grissom’s MR-4 flight. The beneficiary of a major restoration effort, Liberty Bell 7 is now on display at the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center. The spacecraft’s explosive hatch was never found.

As for Gus Grissom, ultimate vindication of his character and competence came in the form of his being named by NASA as Commander for the first flights of Gemini and Apollo. Indeed, Grissom and rookie astronaut John W. Young successfully made the first manned Gemini flight in March of 1965 during Gemini-Titan 3. Later, Grissom, Edward H. White II and Roger B. Chaffee trained as the crew of Apollo 1 which was slated to fly in early 1967. History records that their lives were cut short in the tragic and infamous Apollo 1 Spacecraft Fire of Friday, 27 January 1967.

Fifty-two years ago this month, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Bartsow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Seventy-five years ago today, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most haunting and intriguing stories in the annals of aviation history. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

Thirty-two years ago this month, the seven member crew of STS-51L were killed when the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch from LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The tragedy was the first fatal in-flight mishap in the history of American manned spaceflight.

In remarks made at a memorial service held for the Challenger Seven in Houston, Texas on Friday, 31 January 1986, President Ronald Wilson Reagan expressed the following sentiments:

“The future is not free: the story of all human progress is one of a struggle against all odds. We learned again that this America, which Abraham Lincoln called the last, best hope of man on Earth, was built on heroism and noble sacrifice. It was built by men and women like our seven star voyagers, who answered a call beyond duty, who gave more than was expected or required and who gave it little thought of worldly reward.”

We take this opportunity to remember the noble fallen:

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, Commander

Michael John Smith, Pilot

Ellison S. Onizuka, Mission Specialist One

Judith Arlene Resnik, Mission Specialist Two

Ronald Erwin McNair, Mission Specialist Three

S.Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist One

Gregory Bruce Jarvis, Payload Specialist Two

Speaking for grieving families and countrymen, President Reagan closed his eulogy with these words:

“Dick, Mike, Judy, El, Ron, Greg and Christa – your families and your country mourn your passing. We bid you goodbye. We will never forget you. For those who knew you well and loved you, the pain will be deep and enduring. A nation, too, will long feel the loss of her seven sons and daughters, her seven good friends. We can find consolation only in faith, for we know in our hearts that you who flew so high and so proud now make your home beyond the stars, safe in God’s promise of eternal life.”

Tuesday, 28 January 1986. We Remember.