Sixty-one years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, triumph quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 mothership at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the X-2′s forebody and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, it was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded it in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

Fifty-one years ago this month, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Bartsow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

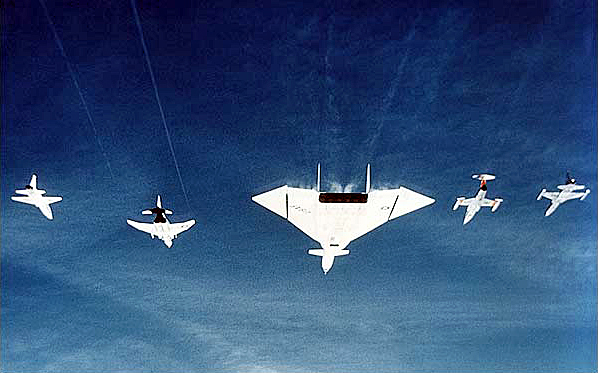

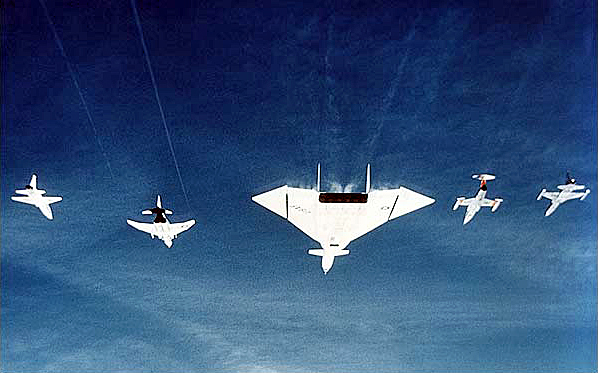

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Forty-nine years ago this month, NASA Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong narrowly escaped with his life when he was forced to eject from the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle in which he was training. Armstrong punched-out only 200 feet above ground level and spent just 4 seconds in the silk before safely landing.

The Lunar Module (LM) was the vehicle used by Apollo astronauts to land on and depart from the lunar surface. This unique spacecraft consisted of separate descent and ascent rocket-powered stages. The powered descent phase was initiated at 50,000 feet AGL and continued all the way to landing. The powered ascent phase lasted from lunar lift-off to 60,000 feet AGL.

It was recognized early in the Apollo Program that landing a spacecraft on the lunar surface under vacuum conditions would be very challenging to say the least. To maximize their chances for doing so safely, Apollo astronauts would need piloting practice prior to a lunar landing mission. And they would need an earth-bound vehicle that flew like the LM to get that practice.

The Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) was the answer to the above. The LLRV employed a turbojet engine that provided vertical thrust to cancel five-sixths of its weight since the gravity on the Moon is one-sixth that of Earth. The vehicle was also configured with dual lift rockets to provide vertical and horizontal motion. LLRV 3-axis attitude control was provided by a series of 16 small thrusters.

The LLRV was described by one historical NASA document as being “unconventional, contrary and ugly”. Known as the “Flying Bedstead”, the LLRV was designed for the specific purpose of simulating LM flight during the terminal phase of a lunar landing. The LLRV was not easy to fly in the “low and slow” flight regime in which it operated. The type was aesthetically unattractive in the extreme.

A pair of LLRV’s were constructed by Bell Aerosystems and flight tested at what is now the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center starting in October 1964. These vehicles were subsequently shipped to Ellington Air Force Base in Texas by early 1967. A number of flight crew, including Neil Armstrong, began LLRV flight training shortly thereafter.

Neil Armstrong made his first LLRV flight on Monday, 27 March 1967 in LLRV No. 1. (This occurred two months after the horrific Apollo 1 Fire.) Armstrong continued flight training in the LLRV over the next year in preparation for what would ultimately be the first manned lunar landing attempt in July of 1969

On Monday, 06 May 1968, Armstrong was flying LLRV No. 1 when the vehicle began losing altitude as its lift rockets lost thrust. Using turbojet power, Armstrong was able to get the LLRV to climb. As he did so, the vehicle made an uncommanded pitch-up and roll over. The attitude control system was unresponsive. The pilot had no choice but to eject.

Neil Armstrong ejected from the LLRV at 200 feet AGL as LLRV No. 1 crashed to destruction. The pilot was subjected to an acceleration of 14 G’s as his rocket-powered, vertically-seeking ejection seat functioned as designed. Armstrong got a full chute, but made only a few swings in same before safely touching-down back on terra firma. His only injury was to his tongue, which he accidently bit at the moment of ejection seat rocket motor ignition.

A mishap investigation board attributed the LLRV mishap to a design deficiency that allowed the helium gas pressurant of the lift rocket and attitude control system fuel tanks to be be accidently depleted. Thus, propellants could not be delivered to the lift rockets and attitude control system thrusters.

Neil Armstrong and indeed all of the Apollo astronauts who landed on the Moon trained in improved variants of the LLRV known as the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV). This training was absolutely crucial to the success of the half-dozen Apollo crews who landed on the Moon. Indeed, there was no other way to adequately simulate moon landings except by flying the LLTV.

Sixty-one years ago this month, the No. 1 USAF/Martin XB-51 light attack bomber prototype crashed during take-off from El Paso International Airport in Texas. The cause of the mishap was attributed to premature rotation of the aircraft leading to an unrecoverable stall.

A product of the post-WWII 1940’s, the Martin XB-51 was envisioned as a jet-powered replacement for the piston-driven Douglas A-26 Invader. The swept-wing XB-51 utilized a unique propulsion system which consisted of a trio of General Electric J47 turbojets. Demonstrated top speed was 560 knots at sea level.

The XB-51 was a good-sized airplane. With a length of 85 feet and a wing span of 53 feet, the XB-51 had a nominal take-off weight of around 56,000 lbs. The wings were swept 35 degrees aft and incorporated 6 degrees of anhedral. The latter feature was utilized to counter the large dihedral effect produced by the type’s tee-tail.

A pair of XB-51 aircraft were built by Martin for USAF. Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-0685) first took to the air in October of 1949 followed by the flight debut of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) in April of 1950. The air crew consisted of a pilot who sat underneath a large, clear canopy and a navigator housed within the fuselage.

While the XB-51 flew hundreds of hours in flight test and made many lasting contributions to the aviation field, the aircraft never went into production. This fate was primarily the result of having lost a head-to-head competitive fly-off against the English Electric Canberra B-57A light attack bomber in 1951.

The No. 1 XB-51 aircraft was lost on Sunday, 25 March 1956 during take-off from El Paso International Airport. The mishap aircraft accelerated more slowly than normal and with the end of the runway coming up quickly, the pilot rotated the aircraft in a attempt to get airborne. Unfortunately, the rotation was premature and the wing stalled. The aircraft exploded on impact and the crew of USAF Major James O. Rudolph and Staff-Sargent Wilbur R. Savage were killed.

The loss of the No. 1 XB-51 was preceded by the destruction of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) on Friday, 09 May 1952. That tragedy occurred during low-altitude aerobatic maneuvers at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The pilot, USAF Major Neil H. Lathrop, perished in the resulting post-impact explosion and inferno.

As a footnote, the historical record reveals that the XB-51 was never assigned an official nickname by the Air Force. However, it was unofficially referred to in some aviation circles as the Panther. Due to its prominently-long fuselage, the less majestic monicker of “Flying Cigar” was sometimes used as well.

Fifty years ago to the day, the Apollo 204 prime crew perished as fire swept through their Apollo Block I Command Module (CM). The Apollo 204 crew of Command Pilot Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White II and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee had been scheduled to make the first manned flight of the Apollo Program some three weeks hence.

On Friday, 27 January 1967, during a plugs-out ground test on LC-34 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, a fire broke out in the Apollo 204 spacecraft at 23:31:04 UTC (6:31:04 pm EST). Shortly after, a chilling cry was heard across the communications network from Astronaut Chaffee: “We’ve got a fire in the cockpit”.

Believed to have started just below Grissom’s seat, the fire quickly erupted into an inferno that claimed the men’s lives in less than 30 seconds. While each received extensive 3rd degree burns, death was attributed to toxic smoke inhalation.

The Apollo 204 fire was most likely brought about by some minor malfunction or failure in equipment or wire insulation. This failure, which was never positively identified, initiated a sequence of events that culminated in the conflagration.

The post-mishap investigation uncovered numerous defects in CM Block I design, manufacturing, and workmanship. The use of a (1) pure oxygen atmosphere pressurized to 16.7 psia and (2) complex 3-component hatch design (that took a minimum of 90 seconds to open) sealed the astronauts’ fate.

A haunting irony of the tragedy is that America lost her first astronaut crew, not in the sideral heavens, but in a spacecraft that was firmly rooted to the ground.

Sixty years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, victory quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 motherhip at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the X-2′s forebody and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, it was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded it in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

Fifteen years ago today, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor caused the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit paydirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared indifferent to the scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s historic scramjet flights that originated right down the road at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and its crew was lost. The space agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight and Phase-Out efforts. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

Seventy-three years ago this month, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most intriguing and haunting stories in the annals of aviation. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

Thirty years ago today, the seven member crew of STS-51L were killed when the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch from LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The tragedy was the first fatal in-flight mishap in the history of American manned spaceflight.

In remarks made at a memorial service held for the Challenger Seven in Houston, Texas on Friday, 31 January 1986, President Ronald Wilson Reagan expressed the following sentiments:

“The future is not free: the story of all human progress is one of a struggle against all odds. We learned again that this America, which Abraham Lincoln called the last, best hope of man on Earth, was built on heroism and noble sacrifice. It was built by men and women like our seven star voyagers, who answered a call beyond duty, who gave more than was expected or required and who gave it little thought of worldly reward.”

We take this opportunity to remember the noble fallen:

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, Commander

Michael John Smith, Pilot

Ellison S. Onizuka, Mission Specialist One

Judith Arlene Resnik, Mission Specialist Two

Ronald Erwin McNair, Mission Specialist Three

S.Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist One

Gregory Bruce Jarvis, Payload Specialist Two

Speaking for grieving families and countrymen, President Reagan closed his eulogy with these words:

“Dick, Mike, Judy, El, Ron, Greg and Christa – your families and your country mourn your passing. We bid you goodbye. We will never forget you. For those who knew you well and loved you, the pain will be deep and enduring. A nation, too, will long feel the loss of her seven sons and daughters, her seven good friends. We can find consolation only in faith, for we know in our hearts that you who flew so high and so proud now make your home beyond the stars, safe in God’s promise of eternal life.”

Tuesday, 28 January 1986. We Remember.

Forty-nine years ago today, the Apollo 204 prime crew perished as fire swept through their Apollo Block I Command Module (CM). The Apollo 204 crew of Command Pilot Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White II and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee had been scheduled to make the first manned flight of the Apollo Program some three weeks hence.

On Friday, 27 January 1967, during a plugs-out ground test on LC-34 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, a fire broke out in the Apollo 204 spacecraft at 23:31:04 UTC (6:31:04 pm EST). Shortly after, a chilling cry was heard across the communications network from Astronaut Chaffee: “We’ve got a fire in the cockpit”.

Believed to have started just below Grissom’s seat, the fire quickly erupted into an inferno that claimed the men’s lives in less than 30 seconds. While each received extensive 3rd degree burns, death was attributed to toxic smoke inhalation.

The Apollo 204 fire was most likely brought about by some minor malfunction or failure in equipment or wire insulation. This failure, which was never positively identified, initiated a sequence of events that culminated in the conflagration.

The post-mishap investigation uncovered numerous defects in CM Block I design, manufacturing, and workmanship. The use of a (1) pure oxygen atmosphere pressurized to 16.7 psia and (2) complex 3-component hatch design (that took a minimum of 90 seconds to open) sealed the astronauts’ fate.

A haunting irony of the tragedy is that America lost her first astronaut crew, not in the sideral heavens, but in a spacecraft that was firmly rooted to the ground.