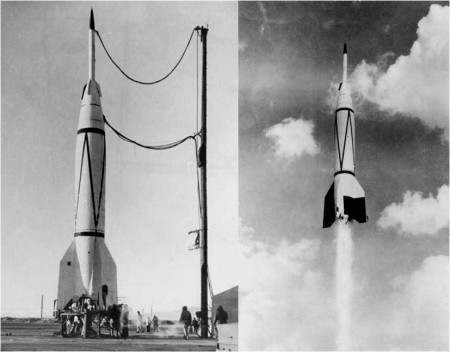

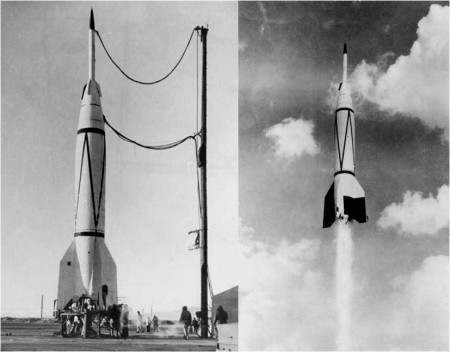

Sixty-four years ago this week, a United States two-stage liquid-fueled rocket reached a then-record altitude of 250 miles. Launch took place from Pad 33 at White Sands Proving Ground (WSPG), New Mexico.

The Bumper Program was a United States Army effort to reach flight altitudes and velocities never before achieved by a rocket vehicle. The name “Bumper” was derived from the fact that the lower stage would act to “bump” the upper stage to higher altitude and velocity than it (i.e., the upper stage) was able to achieve on its own.

The Bumper Program, which was actually part of the Army’s Project Hermes, officially began on Friday, 20 June 1947. The project team consisted of the General Electric Company, Douglas Aircraft Company and Cal Tech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. A total of eight (8) test flights took place between May 1948 and July 1950.

The Bumper two-stage configuration consisted of a V-2 booster and a WAC Corporal upper stage. The V-2’s had been captured from Germany following World War II while the WAC Corporal was a single stage American sounding rocket. The launch stack measured 62 feet in length and weighed around 28,000 pounds.

Propulsion-wise, the V-2 booster generated 60,000 pounds of thrust with a burn time of 70 seconds. The WAC Corporal rocket motor produced 1,500 pounds of thrust and had a burn time of 47 seconds.

The flight of Bumper-WAC No. 1 occurred on Thursday, 13 May 1948. This was an engineering test flight in which the WAC Corporal achieved a peak altitude of 79 miles. Unfortunately, the next three (3) flights were plagued by development problems of one kind or another and failed to achieve an altitude of even 10 miles.

Bumper-WAC No. 5 was fired from WSPG on Thursday, 24 February 1949. The V-2 burned-out at an altitude of 63 miles and a velocity of 3,850 feet per second. The WAC Corporal accelerated to a maximum velocity of 7,550 feet per second and then coasted to an apogee of 250 miles.

With generation of a very thin bow shock layer and high aerodynamic surface heating levels, the flight of Bumper-WAC No. 5 can be considered as the first time a man-made flight vehicle entered the realm of hypersonic flight. Notwithstanding that achievement, its maximum Mach number of 7.6 would be eclipsed in July of 1950 when Bumper-WAC No. 7 reached Mach 9.

Three (3) more Bumper-WAC missions would follow Bumper-WAC No.5. While Bumper-WAC No. 6 would fly from WSPG, the final two (2) missions were conducted from an isolated Florida launch site in July of 1950.

The hot, bug-infested Floridian launch location, springing-up amongst sand dunes and scrub palmetto, would one day become the seat of American spaceflight. It was known then as the Joint Long-Range Proving Ground. Today, we know it as Cape Canaveral.

The Bumper Program successfully demonstrated the efficacy of the multi-staging concept. Bumper also provided valuable flight experience in stage separation and high altitude rocket motor ignition systems. In short, Bumper played a vital role in helping America successfully develop its ICBM, satellite and manned spaceflight capabilities.

While its historical significance, and even its existence, has been lost to many here in the 21st Century, the Bumper Program played a major role in our quest for the Moon. As such, it will forever hold a hollowed place in the annals of United States aerospace history.

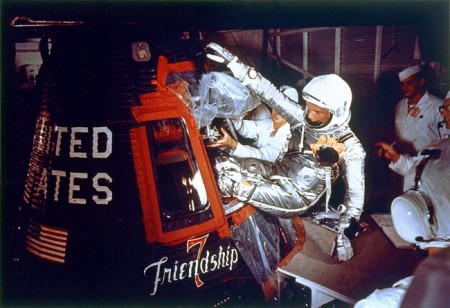

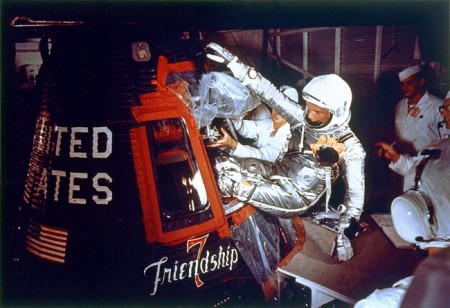

Fifty-one years ago this week, Project Mercury Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn’s spacecraft name and mission call sign was Friendship 7.

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 14 at 14:47:39 UTC on Tuesday, 20 February 1962. It was the first time that the Atlas LV-3B booster was used for a manned spaceflight.

Three-hundred and twenty seconds after lift-off, Friendship 7 achieved an elliptical orbit measuring 143 nm (apogee) by 86 nm (perigee). Orbital inclination and period were 32.5 degrees and 88.5 minutes, respectively.

The most compelling moments in the United States’ first manned orbital mission centered around a sensor indication that Glenn’s heat shield and landing bag had become loose at the beginning of his second orbit. If true, Glenn would be incinerated during entry.

Concern for Glenn’s welfare persisted for the remainder of the flight and a decision was made to retain his retro package following completion of the retro-fire sequence. It was hoped that the 3 straps holding the retro package would also hold the heat shield in place.

During Glenn’s return to the atmosphere, both the spent retro package and its restraining straps melted in the searing heat of re-entry. Glenn saw chunks of flaming debris passing by his spacecraft window. At one point he radioed, “That’s a real fireball outside”.

Happily, the spacecraft’s heat shield held during entry and the landing bag deployed nominally. There had never really been a problem. The sensor indication was found to be false.

Friendship 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at a point 432 nm east of Cape Canaveral at 19:43:02 UTC. John Glenn had orbited the Earth three (3) times during a mission which lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds. Within short order, spacecraft and astronaut were successfully recovered aboard the USS Noa.

John Glenn became a national hero in the aftermath of his 3-orbit mission aboard Friendship 7. It seemed that just about every newspaper page in the days following his flight carried some sort of story about his historic fete. Indeed, it is difficult for those not around back in 1962 to fully comprehend the immensity of Glenn’s flight in terms of what it meant to the United States and indeed the free world.

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. will turn 92 on 18 July 2013. His trusty steed, the Friendship 7 spacecraft, is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Five years ago this month, a United States Navy STANDARD Missile SM-3 Block IA intercepted and destroyed a failed NRO satellite at an altitude of 133 nautical miles. The relative velocity at intercept was in excess of 22,000 mph.

The United States Navy/Raytheon Missile Systems SM-3 (RIM-161) is the sea-based arm of the Missile Defense Agency’s Ballistic Missile Defense System (BMDS). The 3-stage missile carries a Kinetic Warhead (KW) that provides an exoatmospheric hit-to-kill capability.

In order to ensure a lethal hit, the SM-3 KW guides to a specific aimpoint on the target’s airframe. The ability to reliably do so has been impressively demonstrated in a series of intercept flight tests that began in 2002.

SM-3 rounds are launched from the MK-41 Vertical Launcher System (VLS) aboard United States Navy cruisers and destroyers. The at-sea basing concept provides for a high degree of operational flexibility in the ballistic missile intercept mission.

The Lockheed Martin-built USA-193 was launched on a classified mission from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB) at 2100 UTC on Thursday, 14 December 2006. Shortly after reaching orbit, contact with the 5,000-lb satellite was lost.

By January 2008, USA-193’s orbit had decayed to such an extent that its reentry appeared imminent. Such events raise concerns for the safety of those on Earth who reside within the debris impact footprint. However, there was an additional concern in the case of USA-193. The satellite still had about 1,000-lbs of hydrazine onboard.

Should the USA-193 hydrazine tank survive reentry, those living in the impact area would be exposed to a highly toxic cloud of the volatile substance. Officials concluded that the safest thing to do was to destroy the satellite before it reentered the atmosphere.

On Thursday, 21 February 2008, the USS Lake Erie was on station in the Pacific Ocean west of Hawaii. The US Navy cruiser fired a single SM-3 interceptor at 0326 UTC. Minutes later, the missile’s KW took out the satellite and dispersed its hydrazine load into space. Mission accomplished!

In the aftermath of the satellite take-down, Russia and others predictably accused the United States of using the USA-193 hydrazine issue as an excuse to demonstrate SM-3’s anti-satellite capability. While such capability was indeed demonstrated, noteworthy is the fact that all systems modified to execute the satellite intercept were subsequently returned to a ballistic missile defense posture.

Thirty-eight years ago this month, an USAF F-15A Eagle reached an altitude of 30 km (98,425 feet) 207.8 seconds from brake release. The pilot for the record-breaking mission was USAF Major Roger Smith.

Operation Streak Eagle was a mid-1970’s effort by the United States Air Force to set eight (8) separate time-to-climb records using the McDonnell-Douglas F-15 Air Superiority Fighter. These record-setting flights originated from Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Starting on Thursday, 16 January 1975, the 19th pre-production F-15 Eagle aircraft (S/N 72-0119) was used to establish the following time-to-climb records during Operation Streak Eagle:

3 km, 16 January 1975, 27.57 seconds, Major Roger Smith

6 km, 16 January 1975, 39.33 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

9 km, 16 January 1975, 48.86 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

12 km, 16 January 1975, 59.38 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

15 km, 16 January 1975, 77.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

20 km, 19 January 1975, 122.94 seconds, Major Roger Smith

25 km, 26 January 1975, 161.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

The eighth and final time-to-climb record attempt of Operation Streak Eagle took place on Saturday, 01 February 1975. The goal was to set a new time-to-climb record to 30 km. The pilot was required to wear a full pressure suit for this mission.

At a gross take-off weight of 31,908 pounds, the Streak Eagle aircraft had a thrust-to-weight ratio in excess of 1.4. The aircraft was restrained via a hold-down device as the two Pratt and Whitney F100 turbofan engines were spooled-up to full afterburner.

Following hold-down and brake release, the Streak Eagle quickly accelerated during a low level transition following take-off. At Mach 0.65, Smith pulled the aircraft into a 2.5-g Immelman. The Streak Eagle completed this maneuver 56 seconds from brake release at Mach 1.1 and 9.75 km. Rolling the aircraft upright, Smith continued to accelerate the Streak Eagle in a shallow climb.

At an elapsed time of 151 seconds and with the aircraft at Mach 2.2 and 11.3 km, Smith executed a 4-g pull to a 60-degree zoom climb. The Steak Eagle passed through 30 km at Mach 0.7 in an elapsed time of 207.8 seconds. The apex of the zoom trajectory was about 31.4 km. With a new record in hand, Smith uneventfully recovered the aircraft to Grand Forks AFB.

Operation Streak Eagle ended with the capturing of the 30 km time-to-climb record. In December 1980, the aircraft was retired to the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. It is currently held in storage at the Museum and no longer on public display.