Fifty-seven years ago this month, President John F. Kennedy boldly proposed that the United States conduct a manned lunar landing before the end of the 1960’s. The President’s clarion call to glory was delivered during a special session of the United States Congress which focused on what he called “urgent national needs”.

The transcript of that historic speech given on Friday, 25 May 1962 indicates that the ninth and last issue addressed by President Kennedy was simply entitled SPACE. The most stirring and memorable words of that portion of the 35th President’s long ago address to the nation may well be these:

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Although he did not live to see the fulfillment of that monumental goal, history shows that 8 years, 1 month, and 26 days later, the United States of America indeed landed men on the moon and returned them safely to the earth before the decade of the 1960’s was concluded.

Mission Accomplished, Mr. President.

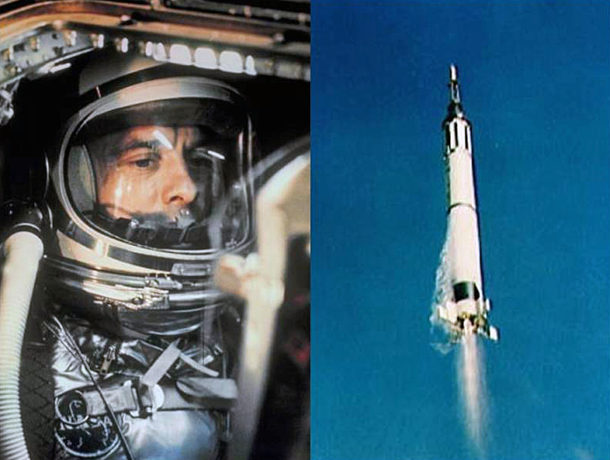

Fifty-six years ago to the day, Mercury Astronaut M. Scott Carpenter orbited the Earth three times aboard his Aurora 7 Mercury spacecraft. In doing so, Carpenter became the second American to reach Earth orbit.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. A total of six (6) flights took place between May of 1961 and May of 1963. The first two (2) flights were suborbital missions while the remainder achieved low Earth orbits. In February of 1962, John H. Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth during the Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) mission.

Deke Slayton was to fly the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) mission. However, before that happened, the dreaded flight surgeon cabal grounded Slayton for what they deemed was a heart murmur. Despite Slayton’s utter incredulity and vehement protests, the decision held. Project Mercury officials maintained that the space program could ill afford the negative political fallout occasioned by the death of an astronaut on-orbit.

With Slayton grounded indefinitely, NASA selected Malcom Scott Carpenter to pilot the Mercury-Atlas 7 mission. Carpenter was member of the Original Seven selected by NASA for the Mercury Program in 1959. He was well prepared for the flight since he had just trained as Glenn’s MA-6 backup. As was the practice at that time, Carpenter named his Mercury spacecraft. The appellation he gave his celestial chariot was Aurora 7.

The launch of MA-7 took place on Thursday, 24 May 1962 from LC-14 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Lift-off time was 12:45:16 UTC. Ascent performance of the stage-and-a-half Atlas D booster was nearly flawless as it inserted Aurora 7 into a 140-nm x 83-nm elliptical orbit. Having been cleared for at least 3 orbits, Carpenter quickly got down to the business of spaceflight.

Much of the activity on the first and second orbits involved Carpenter maneuvering his spacecraft, conducting scientific experiments and observing the Earth from space. Among other discoveries, he discerned that John Glenn’s mysterious “fireflies” were simply particles of ice and frost that had accumulated on the shadow side of the spacecraft. When the spacecraft structure was bumped or vibrated, these particles would disperse from the external surface of the spacecraft and float away into space. Once in the presence of strong sunlight, the particles appeared to glow or be luminescent.

A combination of the astronaut’s spacecraft maneuvering and an intermittently malfunctioning pitch horizon scanner left Carpenter with less than half of his maneuvering fuel left at the start of the third and final orbit. Carpenter compensated admirably by barely using his thrusters during Orbit 3. Indeed, nearing the time of retro-fire, Aurora 7 still had 40 percent of his fuel remaining in both the manual and automatic flight control systems.

As retro-fire approached, the intermittent pitch horizon scanner malfunction reappeared at a most inopportune moment. The automatic stabilization and control system suddenly would not hold Aurora 7 in the proper attitude for retro-fire; heat shield 34 degrees above the horizon at zero yaw angle. Carpenter subsequently switched to manual mode in an attempt to align the spacecraft properly for retro-fire.

When nominal time for retro-fire came, the retro-rockets did not automatically ignite. Carpenter had to do that manually. But he was 3 seconds late. Worst, Aurora 7 was still yawed 25 degree to the right. And to top it off, retro-thrust was 3 percent low. All of this meant that Aurora 7 would overshoot the nominal landing point by 215 nautical miles.

The trip down through the atmosphere was sporty in that Carpenter ran out of attitude control system fuel early during the descent. This meant that there was no means to propulsively damp the side-to-side oscillations that the Mercury spacecraft normally exhibited during reentry. These oscillations became dangerous when they exceeded about 10 degrees. That is, the spacecraft could tumble end-over-end if left unchecked.

Carpenter simultaneously eyed the altimeter and spacecraft angle-of-attack. As the latter built-up dangerously, his only recourse was to manually fire the drogue earlier than planned in attempt to arrest Aurora 7’s oscillatory motion. He did so at 25,000 feet. The spacecraft’s side-to-side oscillations were stopped. Carpenter then deployed his main parachute at 9,500 feet. Splashdown occurred at 17:41:21 UTC at a point 108 nautical miles northeast of Puerto Rico.

Since Aurora 7 was listing badly and help was about an hour away, Carpenter extricated himself from the spacecraft and deployed his life raft. While a radio beacon helped recovery forces locate him, there was no voice communication between the astronaut and his rescuers. Carpenter was on the surface of the briny deep nearly 3 hours before being picked-up by rescue helicopters and safely delivered to the carrier USS Intrepid. Some six (6) hours later, Aurora 7 was brought onboard the USS John R. Pierce.

Mercury-Atlas 7 was Scott Carpenter’s only space mission. A combination of factors, including less than amicable relations with Mercury Mission Control management, led to this being the case. During the intervening years, many stories alluding to pilot error or inattention as the cause of Aurora 7’s landing overshoot have been circulated. Indeed, much like Gus Grissom’s experience with the loss of his Liberty Bell spacecraft, these stories and explanations have been around long enough that they are now accepted as the “truth”.

Criticism of another’s performance comes easily in this world. However, as Theodore Roosevelt once pointed out, it really is “The Man in the Arena” who counts most. It is he and he alone who faces and reacts to the actual moment of trial. No one but he knows the true nature of the reality of that moment and the vicissitudes thereof. While others may criticize, we go on record here to acknowledge and honor M. Scott Carpenter for his heroic and pioneering contributions to early American manned spaceflight.

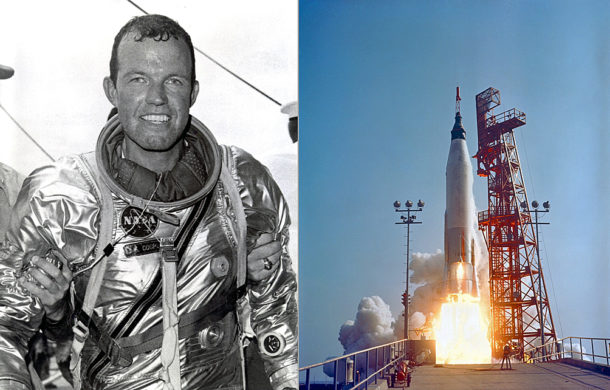

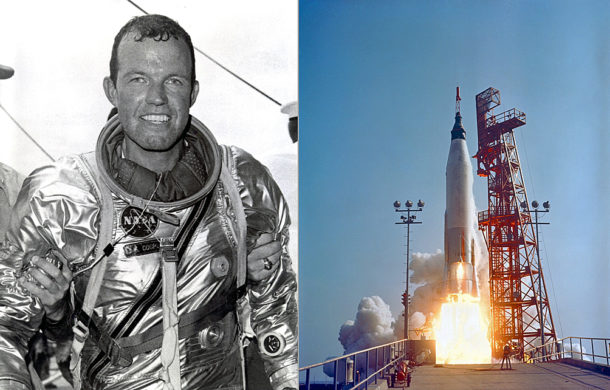

Fifty-five years ago today, NASA Astronaut Leroy Gordon Cooper successfully returned to earth after completing 22 orbits of the home planet. Designated Mercury-Atlas No. 9 (MA-9), Cooper’s flight was the final orbital space mission of the fabled Mercury Program.

Cooper’s eventful space mission began with lift-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-14 at 13:04 hours UTC on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. Splashdown of his Faith 7 spacecraft occurred 70 miles southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, 16 May 1963. Mission total elapsed time was 34 hours 19-minutes 49-seconds.

While the first 19 orbits of the MA-9 mission were mostly unremarkable, the final three orbits severely tested Cooper’s mettle and piloting skills.

By the time that he manually initiated ripple-firing of the retro motors at the end of the 22nd orbit, Cooper was flying a dead spacecraft. The electrical system was not functioning, the environmental control system was saturated with carbon dioxide, and even the mission clock was inoperative. Temperatures in the spacecraft exceeded 130F.

Cooper had to align his spacecraft for retro-fire using the horizon as a reference, used a watch for timing, and manually operated the reaction control system to counter dangerous spacecraft oscillations during the retro burn.

Cooper also manually controlled Faith 7 during entry and initiated deployment of the drogue and main parachutes.

Incredibly, Cooper landed within 5 miles of the recovery ship USS Kearsarge. In so doing, he established the record for the most accurate landing in the Mercury Program. Gordon Cooper was the last American astronaut to orbit the Earth alone.

Forty-five years ago this month, Astronauts Pete Conrad, Joe Kerwin and Paul Weitz became the first NASA crew to fly aboard the recently-orbited Skylab space station. Not only would the crew establish a new record for time in orbit, they would effect critical repairs to America’s first space station which had been seriously damaged during launch.

Skylab was America’s first space station. The program followed closely on the heels of the historic Apollo lunar landing effort. Skylab provided the United States with a unique space platform for obtaining vast quantities of scientific data about the Earth and the Sun. It also served as a means for ascertaining the effects of long-duration spaceflight on human beings.

A Saturn IVB third stage served as Skylab’s core. This huge cylinder, which measured 48-feet in length and 22-feet diameter, was modified for human occupancy and was known as the Orbital Workshop (OWS). With the addition of a Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA) and Airlock Module (AM), Skylab had a total length of 83-feet.

Skylab was also outfitted with a powerful space observatory known as the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). This unit sat astride the MDA and was configured with a quartet of electricity-producing solar panels. The OWS had a pair of solar panels as well. The entire Skylab stack weighed 85 tons.

The Skylab space station (Skylab 1) was placed into a 270-mile orbit using a Saturn V launch vehicle on Monday, 14 May 1973. Upon reaching orbit, it quickly became apparent that all was far from well aboard the space station. The micro-meteoroid shield and solar panel on one side of the OWS had been lost during ascent. The other OWS solar panel was stuck and did not deploy as planned.

With the loss of an OWS solar panel, Skylab would not have enough electrical energy to conduct its mission. The station was also heating up rapidly (temperatures approached 190 F at one point). The lost micro-meteoroid shield also provided protection from solar heating. Sans this protection, internal temperatures could rise high enough to destroy food, medical supplies, film and other perishables and render the OWS uninhabitable.

NASA engineers quickly went to work developing fixes for Skylab’s problems. A mechanism was invented to free the stuck solar panel. A parasol of gold-plated flexible material, deployed from an OWS scientific airlock, was then fashioned and tested on the ground. This material would cover the exposed portion of the OWS and provide the needed thermal shielding.

The onus was now on the Skylab 2 crew of Conrad, Kerwin and Weitz to implement the requisite fixes in orbit. On Friday, 25 May 1973, the Skylab 2 crew and their Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) were rocketed into orbit by a Saturn IB launch vehicle. They quickly rendezvoused with Skylab and verified its sad condition. It was time to get to work.

The first order of business was to try to free the stuck solar panel. As Conrad flew the CSM in close proximity to Skylab, Kerwin held Weitz by the feet as the latter leaned out of the open CSM hatch and attempted to release the stuck solar panel with a pair of special cutters. No joy in spaceville. The solar panel refused to deploy.

The Skylab 2 crew next attempted to dock with Skylab. They tried six times and failed. The CSM drogue and probe was not functioning properly. The crew had to fix it or go home. With great difficulty, they did so and were finally able to dock with Skylab. The overriding objective now was to enter Skylab and successfully deploy the parasol thermal shield.

With Conrad remaining in the CSM, Kerwin and Weitz sported gas masks and cautiously entered Skylab. The temperature inside of the OWS was 130 F. Fortunately, the air was found to be of good quality and the pair went to work deploying the thermal shield through a scientific airlock. The deployment was successful and the temperature started to slowly fall.

It would not be until Thursday, 07 June 1973 that the stuck solar panel would finally be freed. On that occasion, Conrad and Kerwin donned EVA suits and spent 8 hours working outside of Skylab. Their initial efforts with the cutters were unsuccessful.

Undeterred, Conrad and Kerwin improvised and were able to cut the strap that restrained the solar panel. Then, heaving with all their might, the pair finally freed the solar panel. In obedience to Newton’s 3rd Law, as the solar panel deployed in one direction, the astronauts went flying in the other. Happily, they were able to collect themselves and safely reenter the now adequately-powered Skylab.

Skylab 2 went on to spend 28 days in orbits; a record for the time. This record was quickly eclipsed by the Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 crews which spent 59 and 84 days in space, respectively. Skylab was an unqualified success and provided a plethora of terrestrial, solar and human factors data of immense importance to space science. These data played a vital role in the design and development of the ISS.

Skylab was abandoned following the Skylab 4 mission in February of 1974. The plan at the time was to later reactivate the station and raise its orbit using the Space Shuttle when the latter became operational. Unfortunately, a combination of a rapidly deteriorating orbit and delays in flying the Shuttle conspired against bringing this plan to fruition. Skylab reentered the Earth’s atmosphere and broke-up near Australia in July of 1979.

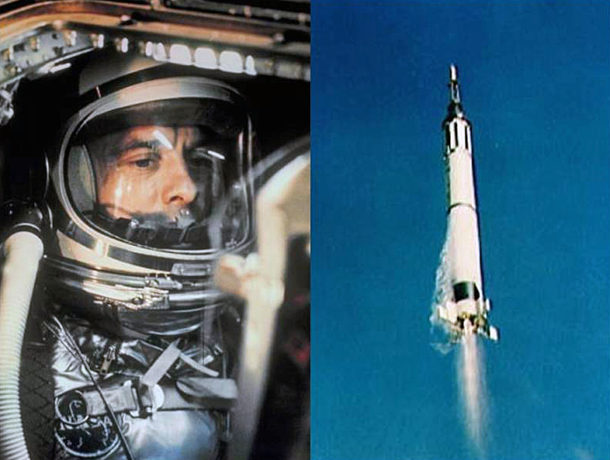

Fifty-seven years ago this week, United States Navy Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became the first American to be launched into space. Shepard named his Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7.

Officially designated as Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) by NASA, the mission was America’s first true attempt to put a man into space. MR-3 was a sub-orbital flight. This meant that the spacecraft would travel along an arcing parabolic flight path having a high point of about 115 nautical miles and a total range of roughly 300 nautical miles. Total flight time would be about 15 minutes.

The Mercury spacecraft was designed to accommodate a single crew member. With a length of 9.5 feet and a base diameter of 6.5 feet, the vehicle was less than commodious. The fit was so tight that it would not be inaccurate to say that the astronaut wore the vehicle. Suffice it to say that a claustrophobic would not enjoy a trip into space aboard the spacecraft.

Despite its diminutive size, the 2,500-pound Mercury spacecraft (or capsule as it came to be referred to) was a marvel of aerospace engineering. It had all the systems required of a space-faring craft. Key among these were flight attitude, electrical power, communications, environmental control, reaction control, retro-fire package, and recovery systems.

The Redstone booster was an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) modified for the manned mission. The Redstone’s uprated A-7 rocket engine generated 78,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. Alcohol and liquid oxygen served as propellants. The Mercury-Redstone combination stood 83 feet in length and weighed 66,000 pounds at lift-off.

On Friday, 05 May 1961, MR-3 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 5 at 14:34:13 UTC. Alan Shepard went to work quickly calling out various spacecraft parameters and mission events. The astronaut would experience a maximum acceleration of 6.5 g’s on the ride upstairs.

Nearing apogee, Shepard manually controlled Freedom 7 about all 3 spacecraft axes. In doing so, he positioned the capsule in the required 34-degree nose-down attitude. Retro-fire occurred on time and the retro package was jettisoned without incident. Shepard then pitched the spacecraft nose to 14 degrees above the horizon preparatory to reentry into the earth’s atmosphere.

Reentry forces quickly built-up on the plunge back into the atmosphere with Shepard enduring a maximum deceleration of 11.6 g’s. He had trained for more than 12 g’s prior to flight. At 21,000 feet, a 6-foot drogue chute was deployed followed by the 63-foot main chute at 10,000 feet. Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 28 seconds after lift-off.

Following splashdown, Shepard egressed Freedom 7 and was retrieved from the ocean’s surface by a recovery helicopter. Both he and Freedom 7 were safely onboard the carrier USS Lake Champlain within 11 minutes of landing. During his brief flight, Shepard had reached a maximum speed of 5,180 mph, flown as high as 116.5 nautical miles and traveled 302 nautical miles downrange.

The flight of Freedom 7 had much the same effect on the country as did Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927. However, in light of the Cold War struggle against the world-wide spread of Soviet communism, Shepard’s flight arguably was more important. Indeed, Alan Shepard became the first of what author Tom Wolfe called in his classic book The Right Stuff, the American single combat warrior.

For his heroic MR-3 efforts, Alan Shepard was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by an appreciative nation. In February 1971, Alan Shepard walked on the surface of the Moon as Commander of Apollo 14. He was the lone member of the original Mercury Seven astronauts to do so. Shepard was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Freedom in 1978.

Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia in July of 1998 at the age of 74. In tribute to this American space hero, naval aviator and US Naval Academy graduate, Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 spacecraft now resides in a place of honor at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.