Twenty-four years ago this week, the seven member crew of STS-51L were killed when the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch from LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. It was the first fatal in-flight accident in American spaceflight history.

In remarks made at a memorial service held for the Challenger Seven in Houston, Texas on Friday, 31 January 1986, President Ronald Wilson Reagan expressed the following sentiments:

“The future is not free: the story of all human progress is one of a struggle against all odds. We learned again that this America, which Abraham Lincoln called the last, best hope of man on Earth, was built on heroism and noble sacrifice. It was built by men and women like our seven star voyagers, who answered a call beyond duty, who gave more than was expected or required and who gave it little thought of worldly reward.”

We take this opportunity now to remember the heroic fallen:

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, Commander

Michael John Smith, Pilot

Ellison S. Onizuka, Mission Specialist One

Judith Arlene Resnik, Mission Specialist Two

Ronald Erwin McNair, Mission Specialist Three

S.Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist One

Gregory Bruce Jarvis, Payload Specialist Two

Speaking for his grieving countrymen, President Reagan closed his eulogy with these words:

“Dick, Mike, Judy, El, Ron, Greg and Christa – your families and your country mourn your passing. We bid you goodbye. We will never forget you. For those who knew you well and loved you, the pain will be deep and enduring. A nation, too, will long feel the loss of her seven sons and daughters, her seven good friends. We can find consolation only in faith, for we know in our hearts that you who flew so high and so proud now make your home beyond the stars, safe in God’s promise of eternal life.”

Tuesday, 28 January 1986. We Remember.

One year ago this month, US Airways Flight 1549 successfully ditched in the Hudson River following loss of thrust in both turbofan engines. Incredibly, all 155 passengers and crew members survived.

US Airways Flight 1549 lifted-off from Runway 4 of New York’s LaGuardia Airport at 18:25:56 UTC on Thursday, 15 January 2009. The Airbus 320-214 (N106US) was making its 16,299th flight. Call sign for the day’s flight was Cactus 1549.

Captain Chesley B. Sullenberger III and First Officer Jeffrey B. Skiles were in the cockpit of Cactus 1549. Donna Dent, Doreen Welsh and Sheila Dail served as flight attendants. Together, these crew members were responsible for the lives of 150 airline passengers.

Following a normal take-off, Cactus 1549 collided with a massive flock of Canadian Geese climbing through 3,000 feet. Numerous bird strikes were experienced. Most critically, both CFM56-5B4/P turbofan engines suffered bird ingestion. As Captain Sullenberger suscinctly described it later, the result was “sudden, complete, symmetrical” loss of thrust.

Quickly assessing their predicament, Captain Sullenberger instinctively knew that he could not get his aircraft back to a land-based runway. He was flying too low and slow to make such an attempt. He would have to ditch his 150,000-pound aircraft in the nearest waterway; the Hudson River.

The story of what ensued following loss of thrust is best told by Captain Sullenberger himself. The reader is therefore directed to chapters 13 and 14 of his post-mishap book entitled “Highest Duty”. The bottom line is that the aircraft was successfully ditched in the Hudson River roughly three and half minutes after loss of thrust.

Once the aircraft was on the water, the crew members evacuated all 150 passengers in less than 4 minutes. People either got into life rafts or stood on the aircraft’s wings. It was very cold. Air temperature was 21F with a windchill factor of 11F. The water temperature registered at 36F.

First responders from the New York Waterway quickly came to the aid of Cactus 1549. A total of fourteen vessels responded to the emergency with the first boat arriving within four minutes of the aircraft coming to a stop.

Many selfless acts of compassion and exemplary displays of valor were observed during Cactus 1549 rescue operations. This was true for those amongst the ranks of the rescuers and rescued alike.

Happily and to the great relief of the US Airways flight crew, there was no loss of life resulting from the emergency ditching of Cactus 1549. Now known as “The Miracle on the Hudson”, the events of that harrowing experience on a winter day in NYC will be forever remembered in the annals of aviation.

For their professional efforts in handling the Cactus 1549 in-flight emergency, Chesley Sullenberger, Jeff Skiles, Donna Dent, Doreen Welsh and Sheila Dail received the rarely-awarded Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators Master’s Medal on Thursday, 22 January 2009.

In part, the Master’s Medal citation read: “The reactions of all members of the crew, the split second decision making and the handling of this emergency and evacuation was ‘text book’ and an example to us all. To have safely executed this emergency ditching and evacuation, with the loss of no lives, is a heroic and unique aviation achievement.”

To which we say: Amen!

Fifty-two years ago this month, a XSM-64 Navaho G-26 flight test vehicle flew 1,075 miles in 40 minutes at a sustained speed of Mach 2.8. It was the 8th flight test of the ill-fated Navaho Program.

The post-World War II era saw the development of a myriad of missile weapons systems. Perhaps the most influential and enigmatic of these systems was the Navaho missile.

Navaho was intended as a supersonic, nuclear-capable, strategic weapon system. It consisted of two (2) stages. The first stage was rocket-powered while the second stage utilized ramjet propulsion. The aircraft-like second stage was configured with a high lift-to-drag airframe in order to achieve strategic reach.

While there were a number of antecedants dating back to 1946, the Navaho Program really began in 1950 as Weapon System 104A. The requirements included a range of 5,500 miles, a minimum cruise speed of Mach 3 and a minimum cruise altitude of 60,000 feet. The payload included an ordnance load of 7,000 pounds delivered within a CEP of 1,500 feet.

North American Aviation (NAA) proposed a 3-phase development plan for WS-104A. Phase 1 involved testing of the missile alone (the X-10) up to Mach 2. Phase 2 covered the testing of the two-stage launch vehicle (the G-26) up to Mach 2.75 and a range of 1,500 miles. Phase 3 would be the ultimate near-production vehicle (the G-38). Only Phase 1 and Phase 2 testing took place.

The Navaho missile-booster vehicle measured 84 feet in length and weighed about 135,000 pounds at lift-off. The launch weight for the booster was 75,000 pounds; most of which was due to the alcohol and LOX propellants. The missile empty weight was 24,000 pounds.

On Friday, 10 January 1958, Navaho G-26 No. 9 (54-3098) lifted-off from LC-9 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Climbing out under 240,000 pounds of thrust from its dual Rocketdyne XLR71-NA-1 rocket motors, missile-booster separation occurred at Mach 3.15 and 73,000 feet. Following air-start and take-over of twin Wright XRJ47-W-5 ramjets, generating a combined thrust of 16,000 pounds, the Navaho missile initiated a near triple-sonic cruise toward the Puerto Rico target area.

As the Navaho missile approached the environs of Puerto Rico, the vehicle was commanded to initiate a sweeping right-hand turn back towards the Cape. Unfortunately, the right intake experienced an unstart and a concommitant, asymmetric loss of thrust. Underpowered and without a restart capability, the vehicle was subsequently commanded to execute a dive into the Atlantic.

Flight No. 8, although only partially successful, flew longer and farther than any Navaho flight test vehicle. Only G-26 Flight No. 6 flew faster (Mach 3.5).

Although three (3) flights would follow G-26 Flight No. 8, all would suffer failure of one kind or another. In point of fact, the Navaho Program had been canceled on Saturday, 13 July 1957. The final six (6) Navaho flights were simply an attempt to extract the most from the remaining missile-booster rounds. Over 15,000 NAA employees lost their jobs the day Navaho died.

Navaho was cancelled primarily due to the ascendancy of the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). Very simply, an ICBM could deliver nuclear ordnance farther, faster and more accurately than a winged, unstealthy strategic missile. Navaho’s relatively numerous technical issues and programmatic delays simply served to drive the final nail into a long-prepared coffin.

While few today remember or even know of the Navaho Program, its technology has had a profound influence on all manner of aerospace vehicles up to the present day. Interestingly, the Space Shuttle launch vehicle concept bears a strong resemblance to the Navaho missile-booster combination. That is, a winged flight vehicle mounted asymmetrically on a longer boost vehicle.

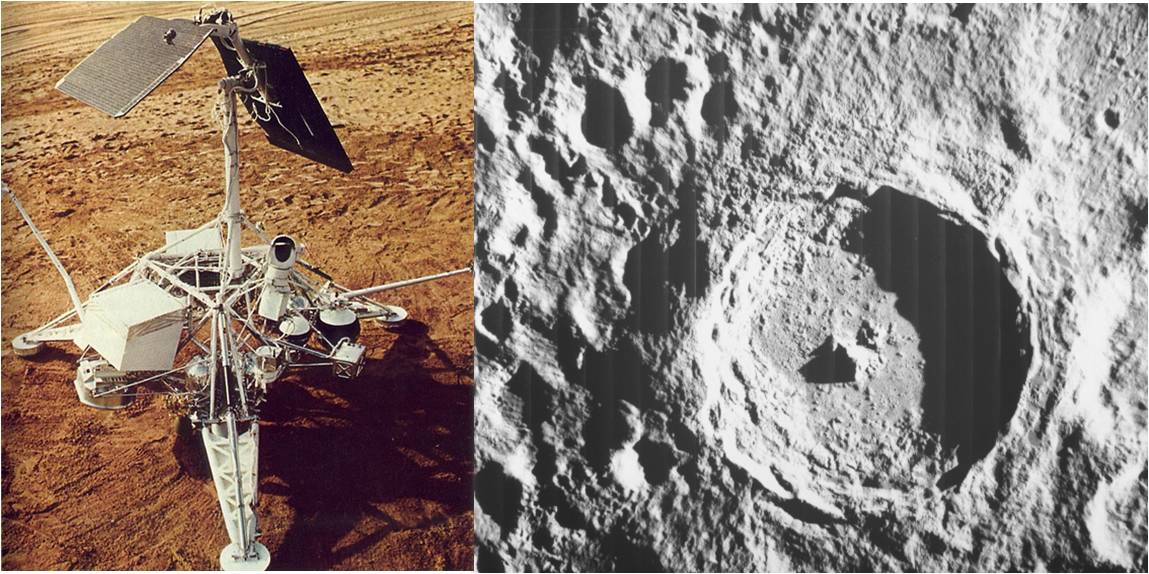

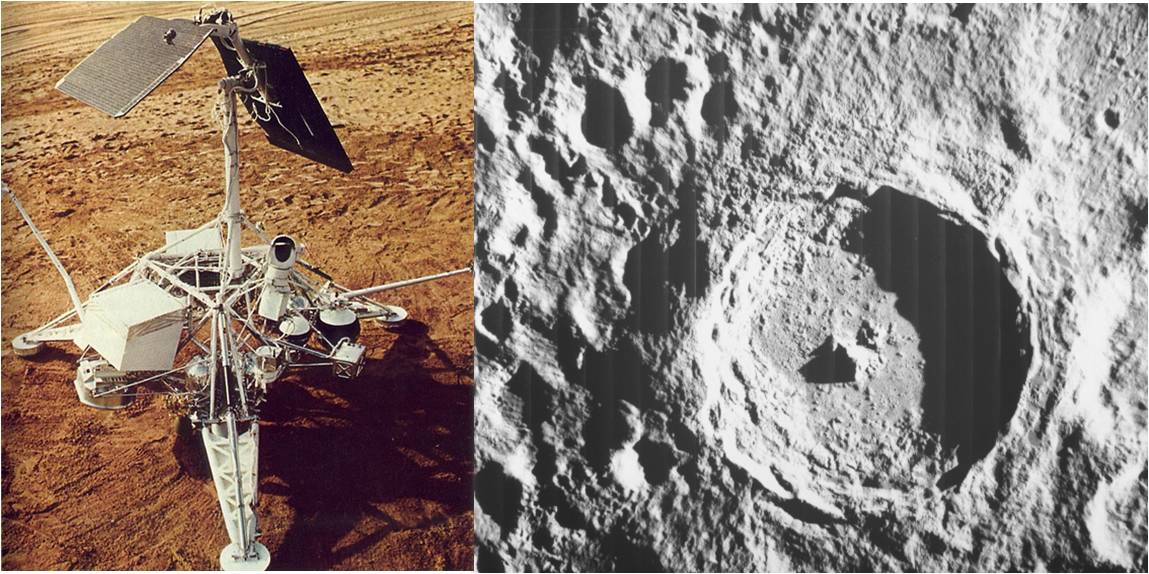

Forty-two years ago this month, the Surveyor 7 spacecraft soft-landed in the lunar highlands near the Crater Tycho. It was the fifth and last Surveyor vehicle to successfully perform an autonomous landing on the Moon.

In preparation for the first manned lunar landing, the United States conducted an extensive investigation of the Moon using Ranger, Lunar Orbiter and Surveyor robotic spacecraft.

Ranger provided close-up photographs of the Moon starting at a distance of roughly 1,100 nautical miles above the lunar surface all the way to impact. Nine (9) Ranger missions were flown between 1961 and 1965. Only the last three (3) missions were successful.

Lunar Orbiter spacecraft mapped 99% of the lunar surface with a resolution of 200 feet or better. Five (5) Lunar Orbiter missions were flown between 1967 and 1968. All were successful.

Surveyor spacecraft were tasked with landing on the Moon and providing detailed photographic, geologic and environmental information about the lunar surface. Seven (7) Surveyor missions were flown between 1966 and 1968. Five (5) spacecraft successfully landed.

The Surveyor spacecraft weighed 2,300 lbs at lift-off and 674 lbs at landing. The 3-legged vehicle stood within a diameter of 15 feet and measured almost 11 feet in height. Surveyor was configured with a television camera, a surface sampler and an alpha-scattering instrument to determine the chemical composition of the lunar soil.

Surveyor 7 was launched from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 36A at 06:30:00.545 UTC on Sunday, 07 January 1968. The ride to the Moon was provided by a General Dynamics Atlas-Centaur launch vehicle. It took almost 68 hours to reach the Moon.

On Wednesday, 10 January 1968, Surveyor 7 successfully landed at 01:05:36 UTC on the lunar surface near the North Rim of Tycho Crater. A total of 20,993 photographs were taken during Surveyor 7’s first lunar day. By Friday, 26 January 1968, Surveyor 7 was powered-down for its first lunar night.

On Monday, 12 February 1968, Surveyor 7 was powered-up for its second lunar day of surface operations. The spacecraft took an additional 45 photographs and operated erratically for 9 earth-days. At 00:24 UTC on Wednesday, 21 February 1968, contact with Surveyor 7 was lost for the final time. By 06:48 UTC, the Surveyor 7 mission was officially terminated.

Although seldom remembered today, the Surveyor Program provided America with a wealth of lunar surface information critical to the Apollo Program. Surveyor’s success provided an added measure of confidence in the attainability of a manned lunar landing. Indeed, seventeen (17) months after Surveyor 7 fell silent, Astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin imprinted the lunar surface with their bootprints at Mare Tranquilitatis.