Thirty-two years ago this month, the Space Shuttle Atlantis was launched on its maiden spaceflight. Known as Mission STS-51J, the flight made Atlantis the fourth member of the Space Shuttle Orbiter fleet to reach Earth orbit.

Mission STS-51J marked the twenty-first orbital flight of the Space Shuttle Program. The primary objective of Atlantis’ first mission was to deploy a Department of Defense (DoD) satellite payload to geostationary orbit. The all-military crew included Commander Karol J. Bobko, Pilot Ronald J. Grabe, Mission Specialists David C. Hilmers and Robert L. Stewart, and Payload Specialist William A. Pailes.

Although classified at the time, the STS-51J payload is suspected to have consisted of a pair of Defense Satellite Communications System (DSCS) satellites. The function of these Lockheed-developed spacecraft was to provide a secure communications capability in support of vital military installations situated across the globe.

Atlantis was launched from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Thursday, 03 October 1985. Lift-off time occurred at 15:15:30 UTC. The new orbiter was successfully inserted into a near-circular orbit having a mean altitude of 219-nm. Orbital inclination and period were 28.5-deg and 94.2 minutes, respectively.

Following deployment from Atlantis’ payload bay, a single Boeing Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) successfully propelled the pair of DSCS satellites into geostationary orbit. With each satellite weighing 5,760 lbs, the total DSCS-IUS stack tipped the scales at 44,020 lbs.

Atlantis orbited the globe 64 times before returning to Earth on Monday, 07 October 1985. The Orbiter touched-down on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California at 17:00:08 UTC. Total mission time was 97 hours, 44 minutes and 38 seconds. From lift-off to landing, Atlantis and her crew flew a total distance of 1,462,203 nm.

History records that Atlantis flew 33 (24.4%) of the 135 missions flown over the life of the Space Shuttle Program. During an “operational” flight career spanning 1985 to 2011, Atlantis and her crews contributed immensely to American spaceflight. Key among many accomplishments were helping to build the International Space Station (ISS), refurbishing the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), launching of the Magellan Probe to Venus, and launching the Galileo Probe to Jupiter.

Like her other stable mates, Atlantis no longer graces the heavens with her presence. She had the honor (?) of flying the final Space Shuttle mission (STS-135) in July of 2011. Now eternally rooted to the ground, Atlantis resides on public display at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

Seventy years ago this week, the rocket-powered USAF/Bell XS-1 experimental aircraft exceeded the speed of sound when it reached a maximum speed of 700 mph (Mach 1.06) at 45,000 feet.

Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York built three copies of the XS-1 under contract to the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). The aircraft were designed to approach and then fly beyond the speed of sound.

The Bell XS-1 was 31-feet in length and had a wing span of 28 feet. Gross take-off weight was around 12,500 lbs. The aircraft had an empty weight of about 7,000 lbs. Propulsion was provided by a Reaction Motors XLR-11 rocket motor capable of generating a maximum thrust of 6,000 lbs.

On the morning of Tuesday, 14 October 1947, the XS-1 (S/N 46-062) dropped away from its B-29 mothership (S/N 45-21800) as the pair flew at 220 mph and 20,000 feet. In the XS-1 cockpit was USAAF Captain and World War II ace Charles E. Yeager. The young test pilot had named the aircraft Glamorous Glennis in honor of his wife.

Following drop, Yeager sequentially-lit all four XLR-11 rocket chambers during a climb and push-over that ultimately brought him to level flight around 45,000 feet. The resulting acceleration profile propelled the XS-1 slightly beyond Mach 1 for about 20 seconds. Yeager then shutdown the rocket, decelerated to subsonic speeds, and landed the XS-1 on Muroc Dry Lake at Muroc Army Airfield, California.

The world would not find out about the daring exploits of 14 October 1947 until December of the same year. As it was, the announcement came from a trade magazine that even today is sometimes referred to as “Aviation Leak”.

Today, Glamorous Glennis is prominently displayed in the Milestones of Flight hall of the National Air and Space Museum located in Washington, DC. For his intrepid piloting efforts in breaking the sound barrier, Chuck Yeager was a co-recipient of the 1948 Collier Trophy.

Twenty-nine years ago today, the Space Shuttle Discovery and her five man crew landed on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base to successfully complete the Return-to-Flight (RTF) mission of STS-26. The flight signaled a resumption of the Space Shuttle Program after a 32-month hiatus in manned spaceflight resulting from the Challenger disaster.

Well chronicled is the tragic loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger and its crew of seven on Tuesday, 28 January 1986. Following lift-off at 16:38 UTC from Cape Canaveral’s LC-39B, the launch vehicle disintegrated 73 seconds into flight. The presidentially-appointed Rogers Commission concluded that the primary cause was failure of an O-ring seal in a field joint of the right Solid Rocket Booster (SRB).

While the SRB O-ring failure was the physical cause of the Challenger mishap, the Rogers Commission brought to light a more fundamental and disturbing reason for the tragedy. Specifically, the very decision to launch Challenger on that unusually cold January morning in Florida was fundamentally flawed.

As masterfully delineated in Dianne Vaughan’s “The Challenger Launch Decision”, a culture of deviance with respect to Shuttle flight safety issues had slowly developed at NASA. Pressure to launch, scarce resources and organizational disconnects contributed to NASA management’s blind spot when it came to Shuttle flight safety. The SRB contractor was culpable as well and for the same reasons.

Following redesign and testing of the SRB field joints and the implementation of a myriad of other fixes, NASA prepared to return the Shuttle to flight. The mission was designated as STS-26. To the Space Shuttle Discovery would go the honor of and the responsibility for flying the RTF mission. STS-26 was to be a five day orbital mission.

A five-member crew was selected by NASA to fly STS-26. Each crew member had spaceflight experience. You remember their names. Mission Commander Frederick H. “Rick” Hauck, Pilot Richard O. Covey, and Mission Specialists John M. “Mike” Lounge, George D. “Pinky” Nelson and David C. Hilmers.

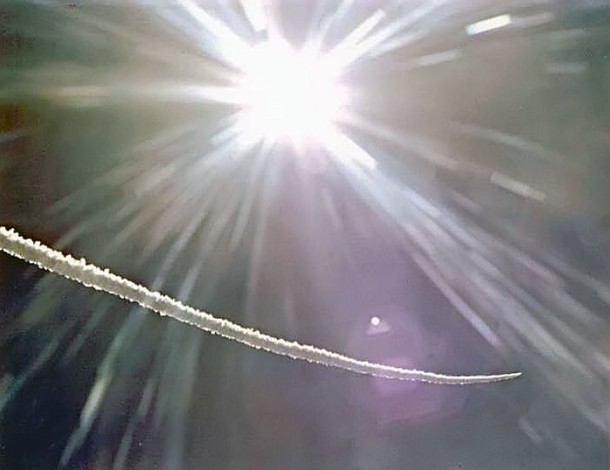

Discovery and her brave crew lifted-off from at 15:37 UTC on Thursday, 29 September 1988 from the very same location that Challenger did; LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Millions watched that day. Some were in the big crowds that formed in and around the Cape complex. Most observed the event on television. Many prayed.

All who watched Discovery lift-off that day could not forget the previous Shuttle flight. Indeed, they remembered what happened just after the CAPCOM’s call: “Challenger, go at throttle-up.” (Ironically, Richard Covey was the CAPCOM who made that very call.) Today, they heard a similar call over the Shuttle communications network: “Discovery, go at throttle-up.” A collective breath was held. After throttle-up, Discovery continued all the way to orbit. YES!!!

In comparison with the launch, initial climbout, and ascent into space, the remainder of the mission seemed somewhat anti-climatic. A Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) was deployed from Discovery’spayload bay to replace the one lost in the Challenger explosion. A multitude of space experiments was conducted by the crew. Fairly standard stuff. Only deboost, the rigors of reentry and the typical dead-stick landing lay ahead.

Discovery landed on Runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base on Monday, 03 October 1988. Main gear touchdown occurred at 16:37 UTC. Approximately, 450,000 American’s witnessed Discovery’s landing in person. A few who did had witnessed its launch in person as well.

The emotion that attended Discovery’s landing in October 1988 was simply overwhelming. Indeed, the experience was an integral part of the healing process for a nation that still grieved the loss of Challenger and her crew. A TIME magazine cover page headline the following week excitedly read: “Whew! America Returns to Space” And indeed it had.

Sixty-one years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, triumph quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 mothership at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the X-2′s forebody and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, it was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded it in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

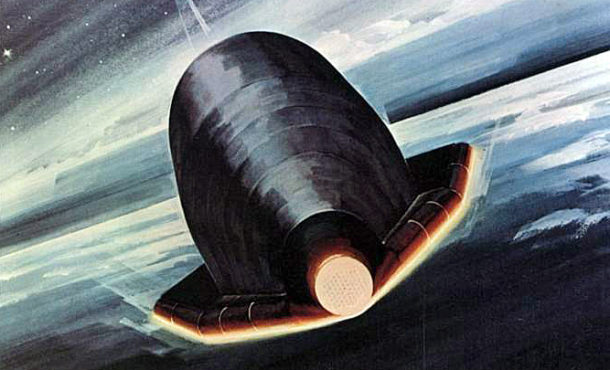

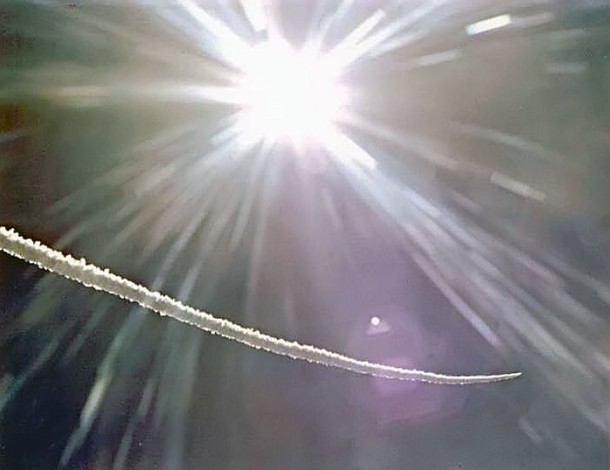

Fifty-four years ago today, the first ASSET flight test vehicle (ASV-1) successfully flew 1,600 nm down the Eastern Test Range (ETR) following launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Boosted atop a Thor launch vehicle, the hypersonic glider reached a maximum velocity of 10,900 mph (Mach 12).

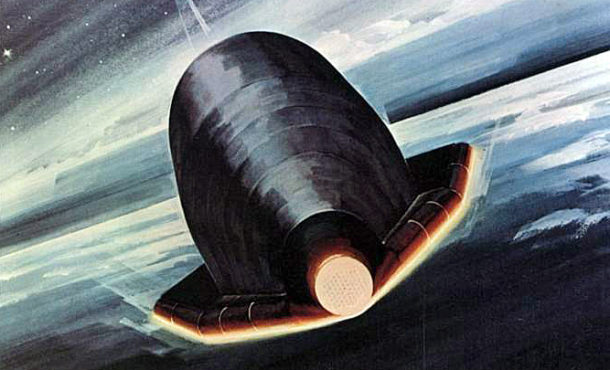

The Aerothermodynamic/Elastic Structural Systems Environmental Tests (ASSET) Program was a United State Air Force flight research effort aimed at exploring hypersonic lifting entry. Programmatic objectives included evaluation of hypersonic lifting vehicle (1) reentry aerodynamic and aerothermodynamic phenomena (2) structural design concepts, and (3) panel flutter characteristics and body flap oscillatory pressures.

The basic ASSET vehicle configuration was a 70-deg delta planform wing with highly-radiused leading edges. The windward surface of this wing was flat and had a 10-deg break in slope roughly two-thirds of the way back from the nose. A blunted cone-cylinder combination was raked into the leeward surface of the wing to form the fuselage of the vehicle. The aft portion of the vehicle was terminated with a flat base region.

There were two (2) types of ASSET flight vehicles. The Aerothermoelastic Vehicle (AEV) variant was flown to investigate windward panel flutter characteristics and body flap oscillatory pressures. A pair of these vehicles were flown. Each weighed AEV weighed 1,225 lbs and was launched into a suborbital flight path by a Douglas Thor booster.

The Aerothermodynamic Structural Vehicle (ASV) variant was flown to determine external airframe surface temperature, heat flux and pressure distributions in hypersonic flight. These data were used to evaluate materials and structural concepts under reentry conditions. A quartet of these vehicles were flight tested. Each ASV weighed 1,130 lbs and was boosted by a Thor-Delta launch vehicle.

ASSET vehicles were boosted to altitudes between 168 KFT and 225 KFT depending on mission type. AEV entry insertion velocity was roughly 13,000 ft/sec while that for ASV shots varied between 16,000 and 19,500 ft/sec. ASSET performed hypersonic flight maneuvers via a combination of aerodynamic and propulsive controls. The windward-mounted body flap was the lone aerodynamic control surface while a set of 3-axis attitude control thrusters were located in the vehicle’s base region.

The first flight of the ASSET Program (ASV-1) took place on Wednesday, 18 September 1963. ASV-1 lift-off occurred at 09:39 UTC from Cape Canaveral’s LC-17B. Due to booster availability issues, a Thor DSV-2F launch vehicle was used for this mission rather than the higher energy Thor-Delta DSV-2G. Insertion altitude and velocity were 203,200 ft and 16,125 ft/sec, respectively. The ASV-1 mission was highly successful with the exception that the vehicle was lost when it sunk in the South Atlantic during recovery operations.

ASV-1 represented the first time in aerospace history that a lifting vehicle configuration had successfully flown a double-digit Mach number reentry trajectory. Five (5) more ASSET vehicles would fly before completion of the flight research program. The sixth and last mission occurred on Tuesday, 23 February 1965.

The ASSET Program garnered a wealth of first-ever hypersonic vehicle aerodynamic, aerothermodynamic, aerothermoelastic and flight controls data. This priceless information and the valuable experience gained during ASSET contributed significantly to the design and flight testing of the PRIME SV-5D and Space Shuttle Orbiter.

Strangely, only one of the ASSET flight test articles was ever recovered successfully. In particular, ASV-3 was recovered following its 1,800 nm suborbital flight down the Eastern Test Range on Wednesday, 22 July 1964. The recovered airframe is currently on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

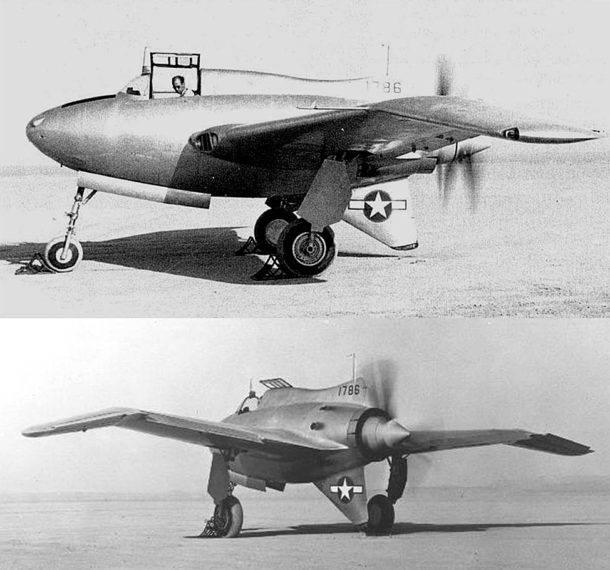

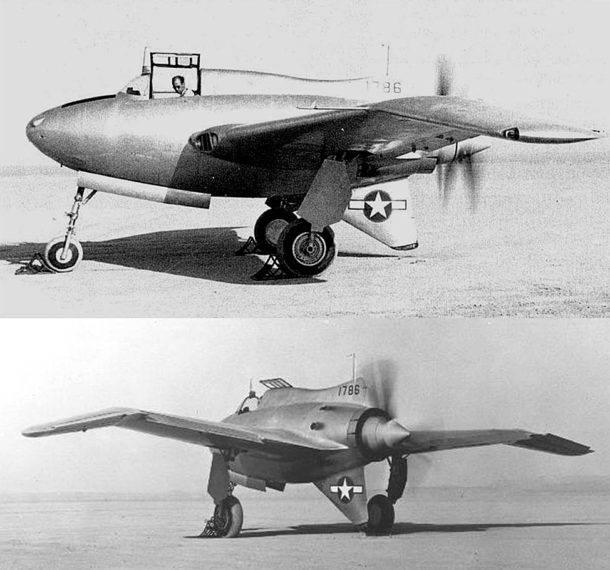

Seventy-four years ago this month, flight testing of the USAAF/Northrop XP-56 Black Bullet commenced at Army Air Base, Muroc in California. Northrop Chief Test Pilot John W. Myers was at the controls of the experimental pursuit aircraft.

The XP-56 (X for Experimental, P for Pursuit) was an attempt at producing a combat aircraft that had superior speed performance relative to conventional fighter-like airframes of the early 1940’s. Towards this end, designers sought to maximize thrust and minimize weight and aerodynamic drag. The product of their labors was a truly strange aircraft configuration.

The XP-56 was essentially a hybrid flying wing to which was added a stubby fuselage to house the pilot and engine. Power was provided by a single Pratt and Whitney R-2800 radial piston engine driving contra-rotating propellers. A pusher power plant installation was selected in the interest of reducing forebody drag. Gross Take-Off Weight (GTOW) came in at 11,350 lbs.

The XP-56’s wing featured a leading edge sweep of 32 degrees and a span of 42.5 feet. The tiny fuselage length of 27.5 feet necessitated the use of elevons for pitch and roll control. Aft-mounted dorsal and ventral tails contributed to directional stability while yaw control was provided by a rudder mounted in the ventral tail.

Under contract to the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), Northrop built a pair of XP-56 airframes; Ship No. 1 (S/N 41-786) and Ship No. 2 (S/N 42-38353). Top speed was advertised as 465 mph at 25,000 feet while the design service ceiling was estimated to be around 33,000 feet. The XP-56 was a short-legged aircraft, having a predicted range of only 445 miles at 396 mph.

XP-56 Ship No. 1 took to the air for the first time on Monday, 06 September 1943. The scene was Rogers Dry Lake at Army Air Field, Muroc (today’s Edwards Air Force Base) in California. Northrop Chief Test Pilot John W. Myers had the distinction of piloting the XP-56. As described below, this distinction was dubious at best.

Myers actually flew XP-56 Ship No. 1 twice on the type’s inaugural day of flight testing. The first flight was really just a hop in the air. Using caution as a guide, Myers flew only 5 feet off the deck in a 30 second flight that covered a distance on the order of 1 mile. The aircraft registered a top speed 130 mph. While the XP-56 exhibited a nose-down pitch tendency as well as lateral-directional sensitivities, Myers was able to complete the flight.

The XP-56’s second foray into the air nearly ended in disaster. Shortly after lift-off at 130 mph, the XP-56 presented pilot Myers with a multi-axis control problem about 50 feet above the surface of Rogers Dry Lake. The strange-looking ship simultaneously yawed to the left, rolled to the right, and pitched down. Holding the control stick with both hands, it was all the Northrop Chief Test Pilot could do keep the nose up and prevent the XP-56 from diving into the ground.

Myers attempted to throttle-back as his errant steed passed through 170 mph. The anomalous yawing-rolling-pitching motions reappeared at this point, once again testing Myers’ piloting skills to the max. The intrepid pilot was finally able to get the XP-56 back on the ground. Albeit, the landing was more of a controlled crash. All of this excitement took place in about 60 seconds over a two mile stretch of Rogers Dry Lake. John Myers had certainly earned his flight pay for the day.

XP-56 Ship No. 1 was demolished during a take-off accident on Friday, 08 October 1943. Although he sustained minor injuries, Myers survived the incident thanks largely to wearing an old polo helmet to protect his valuable cranium. Following the mishap , Myers said that “the airplane wanted to fly upside down and backwards, and finally did!”

XP-56 Ship No. 2 flew a total of ten (10) flights between March and August of 1944. Northrop test pilot Harry Crosby did the piloting honors this time around. Like Myers, Crosby had his hands full trying to fly the XP56. However, Crosby was able to coax the XP-56 up to 250 mph.

Despite valiant attempts to rectify the XP-56’s curious and dangerous handling qualities, Northrop engineers were never able to satisfactorily correct the little beast’s ills. This, coupled with the facts that the XP-56 (1) did not deliver the promised speed performance and (2) was being eclipsed by rapid developments in aircraft technology, the strange aerial concoction became a faded memory by 1945.

A final thought. Just why the XP-56 was given the nickname of Black Bullet is not clear. Ship No. 1 was bare metal and thus silver in appearance. Ship No. 2 sported a dark grey and green camouflage paint scheme. The Bullet moniker could be in deference to the bullet-like nose of the fuselage. In the final analysis, the name Black Bullet probably just sounded cool and evoked a stirring image of a bullet speeding to the target!

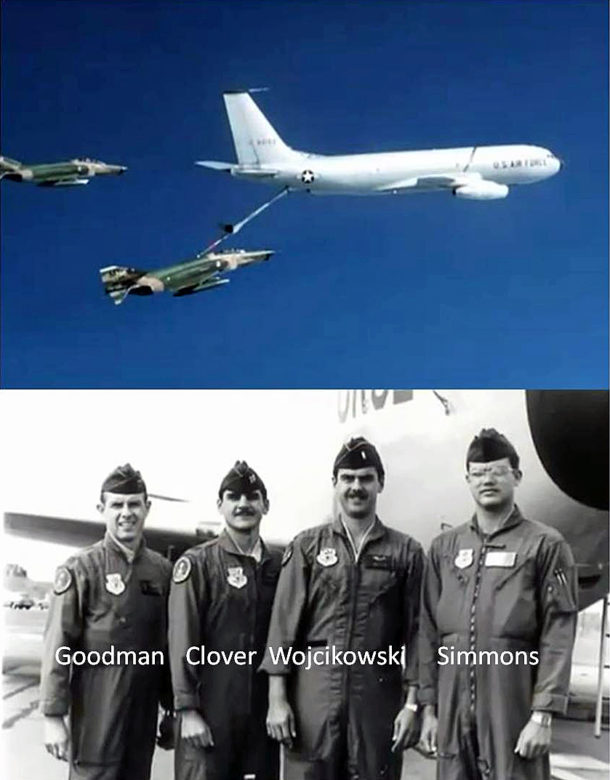

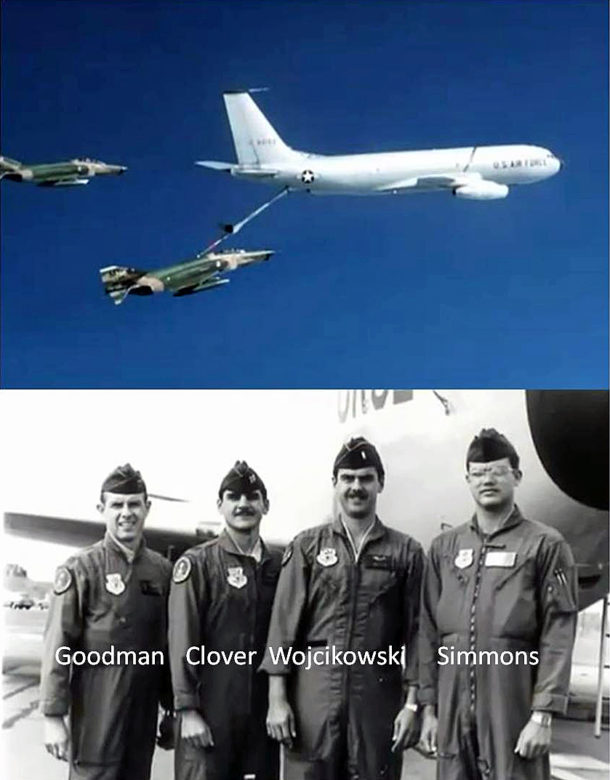

Thirty-four years ago today, the valiant crew of a USAF KC-135 Stratotanker performed multiple aerial refuelings of a stricken USAF F-4E Phantom II over the North Atlantic Ocean. Conducted under extremely perilous flight conditions, the remarkable actions of the aerial tanker’s crew allowed the F-4E to remain aloft long enough to safely divert to an alternate landing field.

On Monday, 05 September 1983, a pair of USAF F-4E Phantom II fighter-bombers departed the United States for a routine flight to Germany. To negotiate the trans-atlantic distance, the F-4E’s would require aerial refueling. As they approached the refueling rendezvous point, one of the aircraft developed trouble with its No. 2 engine. Though still operative, the engine experienced a significant loss of thrust.

The problem with the Phantom’s engine caused it to lose speed and altitude. Further, its No. 1 engine began to overheat as it tried to keep the aircraft airborne. As if this were not enough, the aircraft’s starboard hydraulic system became inoperative. Coupled with the fact that the fuel gauge was edging toward empty, the specter of an ejection and parachute landing in the cold Atlantic looked all but certain for the F-4E crew.

Enter the venerable KC-135 Stratotanker and her crew of Captain Robert J. Goodman, Captain Michael R. Clover, 1st Lt Karol R. Wojcikowski and SSgt Douglas D. Simmons. Based with the 42nd Aerial Refueling Squadron, their immediate problem was two-fold. First, locate and navigate to the pair of F-4E aircraft flying somewhere over the open ocean. Second, get enough fuel to both aircraft so the latter could complete their trans-atlantic hop. Time was of the essence.

Following execution of the rendezvous, the KC-135 crew needed to get their steed out in front of the fuel-hungry Phantoms. The properly operating Phantom quickly took on a load of fuel. However, the stricken aircraft continued to lose altitude as its pilot struggled just to keep the aircraft in the air. By the time the first hook-up occurred, both the F-4E and KC-135 were flying below an altitude of 7,000 feet.

Whereas normal refueling airspeed is 315 knots, the refueling operation between the KC-135 and F-4E occurred below 200 knots. Both aircraft had to fly at high angle-of-attack to generate sufficient lift at this low airspeed. Boom Operator Simmons was faced with a particularly difficult challenge in that the failed starboard hydraulics of the F-4E caused it to yaw to the right. Nonetheless, he was able to make the hook-up with the F-4E refueling recepticle and transfer a bit of fuel to the ailing aircraft.

The transfer of fuel ceased during the first aerial refueling when the mechanical limits of the aircraft-to-aircraft connection were exceeded. The F-4E started to dive as it came off the refueling boom. At this critical juncture, Captain Goodman made the decision to follow the Phantom and get down in front of it for another go at aerial refueling. As the second fuel transfer operation began, the airspeed indicator registered 190 knots; barely above the KC-135’s landing speed.

While additional fuel was transferred to the F-4E, it was still not enough for it to make the divert airfield at Gander, New Foundland. The KC-135 performed two more risky aerial refuelings of the struggling Phantom. The last of which occurred at an altitude of only 1,600 feet above the ocean. At times during these harrowing operations, the KC-135 actually towed the F-4E on its refueling boom to help the latter gain altitude.

At length, the F-4E manged to climb to 6,000 feet and maintain 220 knots as its No. 1 engine began to cool. Able to fend for itself once again, the Phantom punched-off the KC-135 refueling boom. Goodman and crew continued to escort the F-4E to the now-close landing field at Gander, New Foundland. The Phantom pilot greased the landing much to the relief and joy of all.

For their heroic efforts on that eventful September day over the North Atlantic, the crew of the KC-135 received the USAF’s Mackay Trophy for the most meritorious flight of 1983.

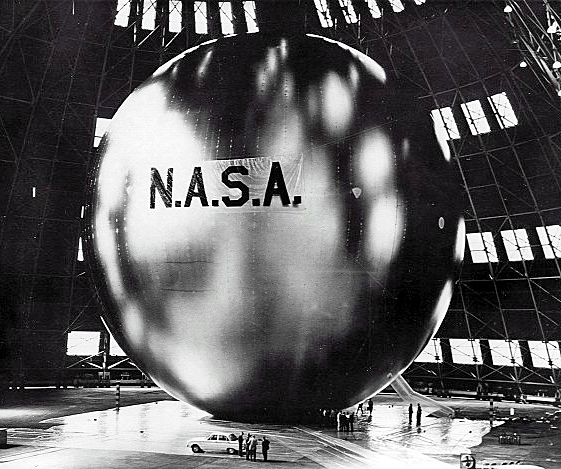

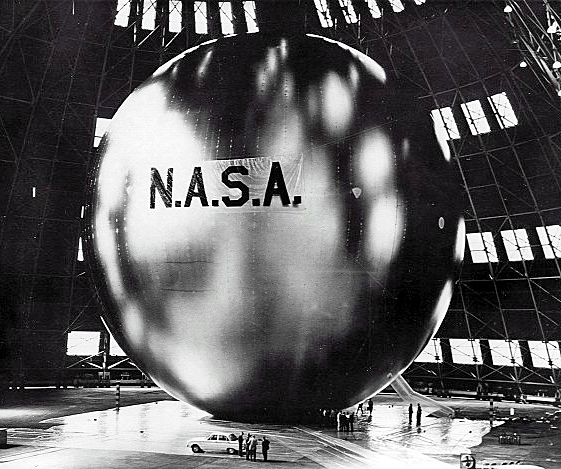

Fifty-seven years ago this month, the United States successfully launched the Echo 1A passive communications satellite into Earth orbit. The 100-foot diameter balloon was among the largest objects ever to orbit the Earth.

A plethora of earth-orbiting communication satellites provide for a global connectivity that is commonplace today. Such was not always the case. Roll the clock back more than a half-century and we find that a global communications satellite system was just a concept. However, keen minds would soon go to work and provide mankind with yet another tangible space age benefit.

Communications satellites are basically of two types; passive and active. A passive communications satellite (PCS) simply reflects signals sent to it from a point on Earth to other points on the globe. An active communications satellite (ACS) can receive, store, modify and/or transmit Earth-based signals.

The earliest idea for a PCS involved the use of an orbiting spherical balloon. The balloon was fabricated from mylar polyester having a thickness of a mere 0.5 mil. The uninflated balloon was packed tightly into a small volume and inserted into a payload canister preparatory to launch. Once in orbit, the balloon was released and then inflated to a diameter of 100 feet.

The system described above materialized in the late 1950′s as Project Echo. The Project Echo satellite was essentially a huge spherical reflector for transcontinental and intercontinental telephone, radio and television signals. The satellite was configured with several transmitters for tracking and telemetry purposes. Power was provided by an array of nickel-cadmium batteries that were charged via solar cells.

Echo 1 was launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida on Friday, 13 May 1960. However, the launch vehicle failed and Echo 1 never achieved orbit. Echo 1A (sometimes referred to as Echo 1) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-17A at 0939 UTC on Friday, 12 August 1960. The Thor Delta launch vehicle successfully placed the 166-lb satellite into a 820-nm x 911-nm orbit.

An interesting characteristic of the Echo satellite was the large oscillation in the perigee of its orbit (485 nm to 811 nm) over several months. This was caused by the influences of solar radiation and variations in atmospheric density. While these factors are just part of the earth-orbital environment, their effects were much more noticeable for Echo due to the type’s large surface area-to-weight ratio.

Echo 1A orbited the Earth until it reentered the Earth’s atmosphere on Saturday, 25 May 1968. Echo 2 was a larger and improved version of Echo 1A. It measured 135-feet in diameter and weighed 547-lb. Echo 2 orbited the Earth between January of 1964 and June of 1969. Other than the Moon, both satellites were the brightest objects observable in the night sky due to their high reflectivity.

The Echo satellites served their function admirably. For a time, they were quite a novelty. However, progress on the ACS scene quickly relegated the PCS to obselescence. Today, virtually all communication satellites are of the ACS variety.

Fifty-four years ago today, NASA chief research pilot Joseph A. Walker flew X-15 Ship No. 3 (S/N 56-6672) to an altitude of 354,200 feet. This flight would mark the highest altitude ever achieved by the famed hypersonic research vehicle.

Carried aloft by NASA’s NB-52A (S/N 52-0003) mothership, Walker’s X-15 was launched over Smith Ranch Dry Lake, Nevada at 17:05:42 UTC. Following drop at around 45,000 feet and Mach 0.82, Walker ignited the X-15’s small, but mighty XLR-99 rocket engine and pulled into a steep vertical climb.

The XLR-99 was run at 100 percent power for 85.8 seconds with burnout occurring around 176,000 feet on the way uphill. Maximum velocity achieved was 3,794 miles per hour which translates to Mach 5.58 at the burnout altitude. Following burnout of the XLR-99, Walker’s X-15 gained an additional 178,200 feet in altitude as it coasted to apogee.

Joe Walker went over the top at 354,200 feet (67 miles). Although he didn’t have much time for sight-seeing, the Earth’s curvature was strikingly obvious to the pilot as he started downhill from his lofty perch. Walker subsequently endured a hefty 5-g’s of eyeballs-in normal acceleration during the backside dive pull-out. The aircraft was brought to a wings-level attitude at 70,000 feet. Shortly after, Walker greased the landing on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The X-15 maximum altitude flight, in which the aircraft’s design altitude was exceeded by more than 100,000 feet, lasted 11 minutes and 8 seconds from drop to nose wheel stop. In that time, Walker and X-15 Ship 3 covered 305 miles in ground range. This mission was Ship No. 3’s 22nd flight and the 91st of the legendary X-15 Flight Research Program.

For Joseph Albert Walker, the 22nd of August 1963 marked his 25th and last flight in an X-15 cockpit. The mission qualified him for Astronaut Wings since he had exceeded the 328,000 foot (100 km) FAI/NASA standard set for such a distinction. However, it would be more than four decades after his historic mission that Walker would be officially be recognized as an astronaut. In a special ceremony conducted at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center on Tuesday, 23 August 2005, Joe Walker was posthumously awarded his Astronaut Wings.

Fifty-three years ago yesterday, the fabled North American X-15 hit a speed of 3,590 mph (Mach 5.23) in a flight that reached an altitude of 103,300 feet. While decelerating through Mach 4.2, the nose gear of the aircraft unexpectedly deployed in flight.

The 114th powered flight of the legendary X-15 Program took place on Friday, 14 August 1964. USAF Major Robert A. Rushworth was at the controls of X-15 Ship No. 2 (S/N 56-6671). The mission would be Rushworth’s 22nd flight in the famed hypersonic aircraft.

X-15 drop from the NB-52A (S/N 52-0003) launch aircraft took place over Delamar Dry Lake, Nevada. Seconds later, Rushworth called for 100% power from the X-15’s XLR-99 liquid-fueled rocket engine as he pulled into a steep climb. He subsequently pushed-over and then leveled-off at 103,300 feet.

XLR-99 burnout occurred 80.3 seconds after ignition. At this juncture, the X-15 was traveling at 3,590 mph; better than 5 times the speed of sound. Following rocket motor burnout, the aircraft slowed and began to lose altitude under the influence of weight and aerodynamic drag.

As the Mach meter needle passed through Mach 4.2, Rushworth heard a loud bang from the airframe. The aircraft became hard to control as it gyrated in pitch, yaw and roll. Rushworth was equal to the moment and brought his troubled steed under control. However, the aircraft had an uncommanded sideslip and Rushworth had to use left aileron to hold the wings level.

Gathering his wits, Rushworth realized that the loud bang he heard was very similar to that which occurred when the nose gear was deployed in the landing pattern. Unaccountably, the X-15 nose gear had deployed in supersonic flight. An unsettling confirmation of Rushworth’s hypothesis came when the pilot spotted smoke, quite a bit of it, in the X-15 cockpit.

As Rushworth neared Edwards Air Force Base, chase aircraft caught up with him and confirmed that the nose gear was indeed down and locked. Further, the tires were so scorched from aerodynamic heating that they probably would disintegrate during touchdown on Rogers Dry Lake. They verily did.

Despite his tireless nose gear, Rushworth was able to control the rollout of his aircraft fairly well on the playa silt. He brought the X-15 to a stop and deplaned. Man and machine had survived to fly another day.

Post-flight analysis revealed that expansion of the X-15 fuselage due to aerodynamic heating was greater than expected. The nose gear door bowed or deformed outward more than anticipated as well. Together, these two anomalies caused the gear uplock hook to bend and release the nose gear. Fixes were subsequently made to Ship No. 2 to prevent a recurrence of the nose gear door deployment anomaly.

Rushworth next flew X-15 Ship No. 2 on Tuesday, 29 September 1964. He reached a maximum speed of 3,542 mph (Mach 5.2) at 97,800 feet. The nose gear door remained locked. However, while decelerating through Mach 4.5, Rushworth heard a bang that was less intense than the previous flight. This time, thermal stresses caused the nose gear door air scoop to deploy in flight. While the aircraft handled poorly, Rushworth managed to get it and himself back on the ground in one piece.

Following another redesign effort, Rushworth took to the air in X-15 Ship No. 2 on Thursday, 17 February 1965. He hit 3,539 mph (Mach 5.27) at 95,100 feet. On this occasion, both the nose gear door and nose gear door scoop remained in place. Unfortunately, the right main landing skid deployed at Mach 4.3 and 85,000 feet.

Thermal stresses were once again the culprit. Despite degraded handling qualities with the landing skid deployed, the valiant Rushworth safely landed the X-15. Upon deplaning, he is reported to have kicked the aircraft in a show of disgust and frustration. Unprofessional maybe, but certainly understandable.

Yet another redesign effort followed in the aftermath of the unexpected main landing skid deployment. This was the third consecutive mission for X-15 Ship No. 2 and Rushworth to experience a thermally-induced landing gear or landing skid deployment anomaly. Happily, subsequent flights of the subject aircraft were free of such vexing issues.