Forty-six years ago this month, the Northrop HL-10 lifting body made its first unpowered free flight. Following drop from NASA’s venerable NB-52B launch aircraft, test pilot Bruce A. Peterson successfully landed the HL-10 on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

A lifting body is a wingless, aircraft-like vehicle which generates aerodynamic lift via the shape and size of its fuselage. The principal application for such a craft is in the realm of hypersonic lifting entry. The attributes of greatest interest here include the type’s favorable lift-to-drag characteristics and effective handling of the entry aerodynamic heating environment.

A true lifting body must operate at Mach numbers that range from hypersonic to subsonic. Flight controls are both aerodynamic and propulsive in nature. The former includes body flaps for pitch and roll control as well as rudders for yaw control. Propulsive thrusters are strategically arranged on the vehicle to augment control about all 3-axes at high altitude where dynamic pressure is low to negligible.

A lifting body’s unconventional shape makes the stability and control design task particularly challenging. The craft must fly at high angles-of-attack and large bank angles during hypersonic flight for trajectory ranging and aero heating accommodation purposes. Lifting bodies can also exhibit nasty lateral-directional handling qualities in the low-speed regime associated with landing.

Lifting bodies first came onto the aerospace scene in the 1960’s. An unmanned vehicle known as PRIME (Precision Recovery Including Maneuvering Entry) successfully flew a trio of suborbital flight tests between December 1966 and April 1967. High speed vehicle flight control was found to be entirely satisfactory.

A total of six (6) manned lifting body vehicles were tested at Edwards Air Force Base between 1963 and 1975. The subject aircraft included the NASA M2-F1, Northrop M2-F2, Northrop M2-F3, Martin X-24A, Martin X-24B and the Northrop HL-10. The primary purpose of this family of research vehicles was to investigate the transonic and subsonic flight characteristics of piloted lifting body aircraft.

The Northrop HL-10 measured 22.17 feet in length, 11.5 feet in height and 15.58 feet in width. The vehicle was configured with an XLR-11 rocket motor capable of generating 6,000 lbs of sea level thrust. GTOW for the single place vehicle was 9,000 lbs. NASA’s lengendary NB-52B mothership served as the launch aircraft. Drop typically took place at 450 mph and 45,000 feet.

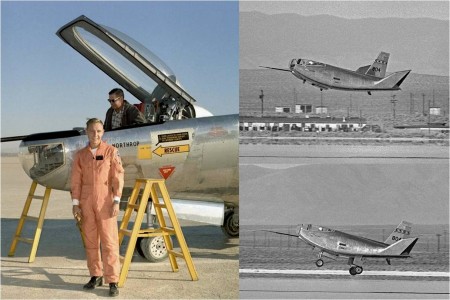

The one and only HL-10 lifting body (S/N 804) made its inaugural free flight on Friday, 22 December 1967. NASA test pilot Bruce A. Peterson was at the controls of the tubby little ship. Since this flight was unpowered, the HL-10 was on the ground just 187 seconds after drop. The HL-10 handled well during the brief test flight and Peterson greased the landing.

The HL-10 flight test program was highly productive. Much was learned in the way of lifting body vehicle stability, control, and handling qualities. The HL-10 holds the distinction of flying higher (90,279 feet) and faster (1,227.5 mph; Mach 1.86) than any lifting body in aviation history.

The HL-10 completed a total of 37 missions (26 powered), the last of which occurred on Friday, 17 July 1970. In addition to Bruce Peterson (who, interestingly, flew only the first flight test), the aircraft was flown by John A. Manke (10 flights), William H. Dana (9 flights), Jerauld R. Gentry (9 flights) and Peter C. Hoag (8 flights).

Happily, the HL-10 airframe survived its flight test program intact. In tribute to its many aeronautical contributions, the aircraft has been preserved for posterity at Edwards Air Force Base. It is currently on public display, mounted on a pole, just outside the gate of the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center (DFRC).