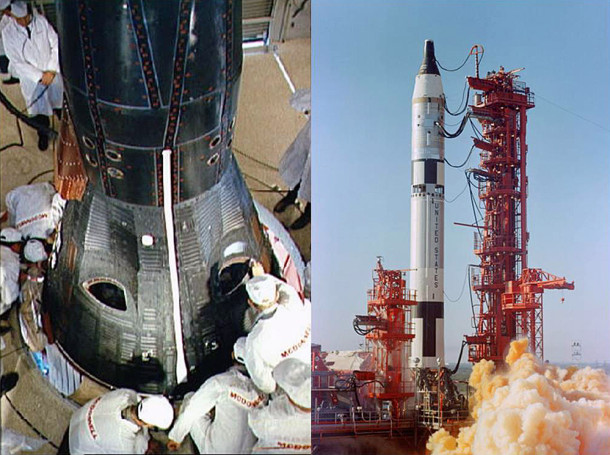

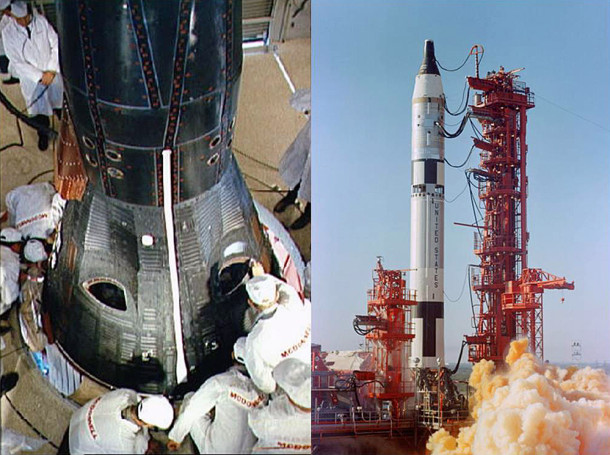

Fifty years ago this week, Gemini III was launched into Earth orbit with astronauts Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom and John W. Young onboard. The 3-orbit mission marked the first time that the United States flew a multi-man spacecraft.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight series. Project Apollo would ultimately land men on the Moon and return them safely to the Earth. In between these historic spaceflight efforts would be Project Gemini.

The purpose of Project Gemini was to develop and flight-prove a myriad of technologies required to get to the Moon. Those technologies included spacecraft power systems, rendezvous and docking, orbital maneuvering, long duration spaceflight and extravehicular activity.

The Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the deboost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbit attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

Gemini-Titan III (GT-3) lifted-off at 14:24 UTC from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Tuesday, 23 March 1965. The two-stage Titan II launch vehicle placed Gemini 3 into a 121 nautical mile x 87 nautical mile elliptical orbit.

Gemini 3’s primary objective was to put the maneuverable Gemini spacecraft through its paces. While in orbit, Grissom and Young fired thrusters to change the shape of their orbital flight path, shift their orbital plane, and dip down to a lower altitude. Gemini 3 was also the first time that a manned spacecraft used aerodynamic lift to change its entry flight path.

As spacecraft commander, Gus Grissom named his cosmic chariot The Molly Brown in reference to a then-popular Broadway show; “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”. Grissom chose the moniker in memory of his first spaceflight experience wherein his Liberty Bell 7 Mercury spacecraft sunk in almost 17,000 feet of water during post-splashdown operations.

At almost two (2) hours into the mission, pilot John Young presented Grissom with his favorite sandwich which had been smuggled onboard. Grissom and Young took a bite of the corned beef sandwich and put it away since loose crumbs could get into spacecraft electronics with catastrophic results. Not amused, NASA management reprimanded the crew after the mission.

Gemini 3 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 19:16:31 UTC following a 3 orbit mission. The spacecraft landed 45 nautical miles short of the intended splashdown point due to a misprediction of aerodynamic lift. Although hot and sea-sick, Commander Grissom refused to open the spacecraft hatches until the recovery ship USS Intrepid came on station.

Nine (9) additional Gemini space missions would follow the flight of Gemini 3. Indeed, the historical record shows that the Gemini Program would fly an average of every two (2) months by the time Gemini XII landed in December 1966. During that period, the United States would take the lead in the race to the Moon that it would never relinquish.

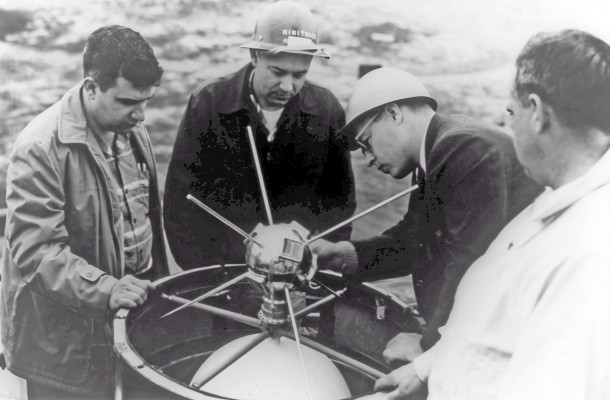

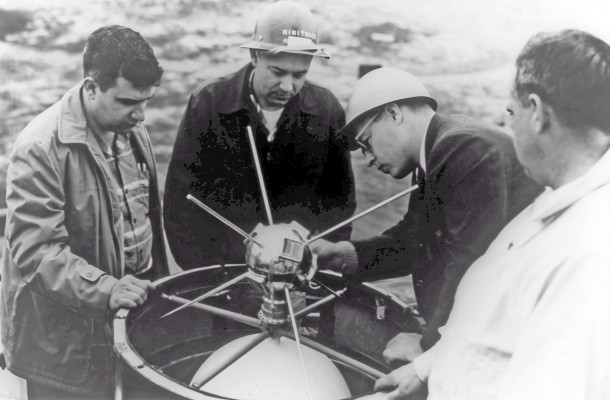

Fifty-seven years ago today, the United States Navy Vanguard Program registered its first success with the orbiting of the Vanguard 1 satellite. The diminutive orb was the fourth man-made object to be placed in Earth orbit.

The Vanguard Program was established in 1955 as part of the United States involvement in the upcoming International Geophysical Year (IGY). Spanning the period between 01 July 1957 and 31 December 1958, the IGY would serve to enhance the technical interchange between the east and west during the height of the Cold War.

The overriding goal of the Vanguard Program was to orbit the world’s first satellite sometime during the IGY. The satellite was to be tracked to verify that it achieved orbit and to quantify the associated orbital parameters. A scientific experiment was to be conducted using the orbiting asset as well.

Vanguard was managed by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). This gave the Vanguard Program a distinctly scientific (rather than military) look and feel. Something that the Eisenhower Administration definitely wanted to project given the level of Cold War tensions.

The key elements of Vanguard were the Vanguard launch vehicle and the Vanguard satellite. The Vanguard 3-stage launch vehicle, manufactured by the Martin Company, evolved from the Navy’s successful Viking sounding rocket. The Vanguard satellite was developed by the NRL.

On Friday, 04 October 1957, the Soviet Union orbited the world’s first satellite – Sputnik I. While the world was merely stunned, the United States was quite shocked by this achievement. A hue and cry went out across the land. How could this have happened? Will the Soviets now unleash nuclear weapons on us from space? And most hauntingly – where is our satellite?

In the midst of scrambling to deal with the Soviet’s space achievement, America would receive another blow to the national solar plexus on Sunday, 03 November 1957. That is the day that the Soviet Union orbited their second satellite – Sputnik II. And this one even had an occupant onboard; a mongrel dog name Laika.

The Vanguard Program was uncomfortably in the spotlight now. But it really wasn’t ready at that moment to be America’s response to the Soviets. After all, Vanguard was just a research program. While the launch vehicle was developing well enough, it certainly was not ready for prime time. The Vanguard satellite was a new creation and had never been used in space.

History records that the first American satellite launch attempt on Friday, 06 December 1957 went very badly. The launch vehicle lost thrust at the dizzying height of 4 feet above the pad, exploded when it settled back to Earth and then consumed itself in the resulting inferno. Amazingly, the Vanguard satellite survived and was found intact at the edge of the launch pad.

Faced with a quickly deteriorating situation, America desperately turned to the United States Army for help. Wernher von Braun and his team at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) responded by orbiting Explorer I on Friday, 31 January 1958. America was now in space!

The Vanguard Program regrouped and attempted to orbit a Vanguard satellite on Wednesday, 05 February 1958. Fifty-seven seconds into flight the launch vehicle exploded. Vanguard was now 0 for 2 in the satellite launching business. Undeterred, another attempt was scheduled for March.

Monday, 17 March 1958 was a good day for the Vanguard Program and the United States of America. At 12:51 UTC, Vanguard launch vehicle TV-4 departed LC-18A at Cape Canaveral, Florida and placed the Vanguard 1 satellite into a 2,466-mile x 406-mile elliptical orbit. On this Saint Patrick’s Day, Vanguard registered its first success and America had a second satellite orbiting the Earth.

Whereas the Soviet satellites weighed hundreds of pounds, Vanguard 1 was tiny. It was 6.4-inches in diameter and weighed only 3.25 pounds. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev mockingly referred to it as America’s “grapefruit satellite”. Small maybe, but mighty as well. Vanguard 1 went on to record many discoveries that helped write the book on spaceflight.

Khrushchev is gone and all of those big Sputniks were long ago incinerated in the fire of reentry. Interestingly, the “grapefruit satellite” is still in space and is the oldest satellite in Earth orbit. Vanguard 1 has completed roughly 200,000 Earth revolutions and traveled over 5.7 billion nautical miles since 1957. It is expected to stay in orbit for another 240 years. Not bad for a grapefruit.

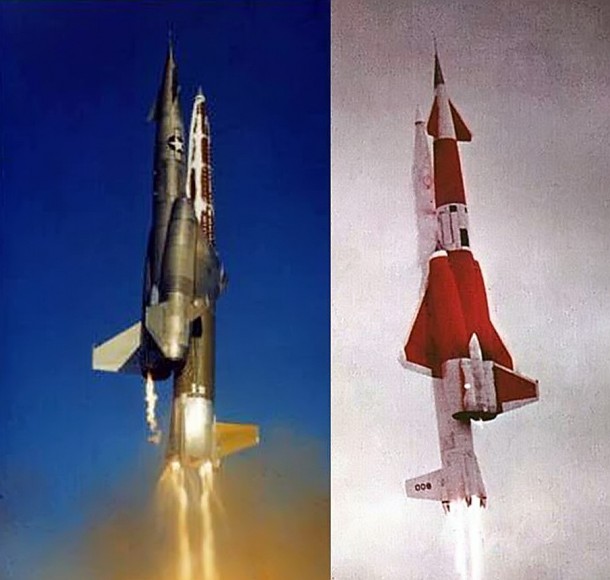

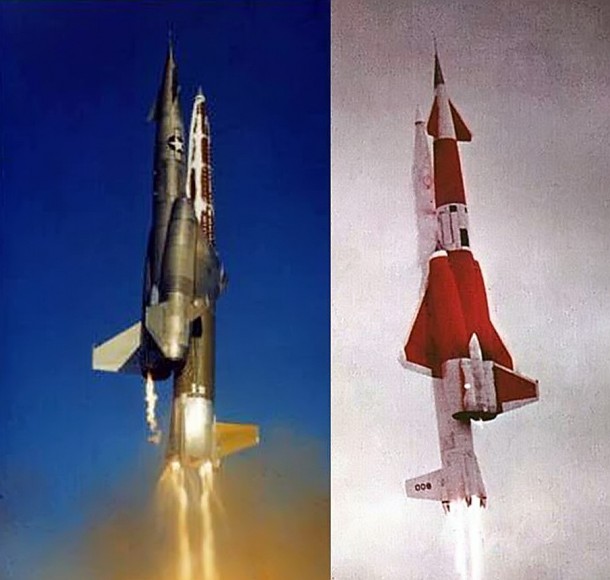

Forty-four years ago this month, the USAF/NASA X-24A lifting body was flown to a speed of 1,036 mph (Mach 1.6) by NASA Research Pilot John Manke. It was the highest speed ever attained by the rocket-powered lifting body.

A lifting body is an unconventional aircraft in that the vehicle generates lift without the benefit of a wing. Rather, the aircraft produces lift by the manner in which its fuselage is shaped.

In the early days of manned spaceflight, there were two schools of thought regarding the preferred mode of entry from orbital flight. One camp favored ballistic entry where the predominant flight force was aerodynamic drag. This was in contradistinction to lifting entry where both aerodynamic lift and drag forces were generated.

Ballistic entry is the more simple approach, but affords little control of the endoatmospheric flight path. This stems from the fact that the landing point for a ballistic entry is largely dictated by the entry vehicle’s velocity and flight path angle at entry interface.

While operationally more complicated, lifting entry provides a positive means for controlling the entry vehicle’s flight path and thus its landing point. At hypersonic speeds, even a small amount of lift markedly enhances entry vehicle downrange and crossrange capability.

Part of the complication of designing a lifting entry vehicle stems from the need to deal with high levels of heating during entry flight. The vehicle’s shape not only dictates its aerodynamic capabilities, but its aerodynamic heating characteristics as well. Thus, issues of flight path control and airframe survivability are interrelated.

The heyday of lifting body flight research spans the period from 1963 to 1975. For the record, the lifting bodies flown in that era include the following vehicles: M2-F1, M2-F2, M2-F3, HL-10, X-24A and X-24B. Each of these aircraft were piloted. All lifting body flight research was conducted at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The X-24A was developed by the Martin Company under contract to the United States Air Force. A single X-24A was produced. It measured 24.5 feet in length and had a gross weight of 11,450 pounds. Airframe empty weight was 6,300 pounds.

Though unconventional in shape, the X-24A incorporated full 3-axis flight controls. The aircraft was powered by the venerable XLR-11 rocket motor. Consisting of four rocket chambers, the XLR-11 was rated at 8,500 pounds of sea level thrust. Maximum burn time was on the order of 140 seconds. All landings of the squat little ship were conducted deadstick.

The X-24A displayed generally good handling characteristics, but had to be flown precisely. Angle-of-attack had to be maintained between about 4 and 12 degrees. Flight at lower and higher angles-of-attack encountered undesirable aerodynamic control and cross-coupling characteristics.

On Monday, 29 March 1971, X-24A (S/N 66-13551) fell away from the B-52B mothership in an effort to fly a maximum speed mission. NASA research pilot John Manke was at the controls. Manke accelerated the aircraft in a climb and reached a record speed of 1,036 mph (Mach 1.6). Interestingly, it was also John Manke who had previously flown the X-24A lifting body to its highest altitude of 71,407 feet on Tuesday, 27 October 1970.

The X-24A, like all of the lifting body aircraft, contributed significantly to the decision to land the Space Shuttle Orbiter deadstick. The lifting bodies, as well as X-aircraft such as the X-1, X-2, and X-15, proved conclusively that an unpowered aircraft could reliably (1) manage its energy state all the way to landing and (2) precisely control its touchdown point.

The X-24A flew a total of 28 flight research missions. Following its final flight, the X-24A was then converted to the radically different-appearing X-24B configuration which flew 36 times. Today, the X-24B is displayed in a place of honor in the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

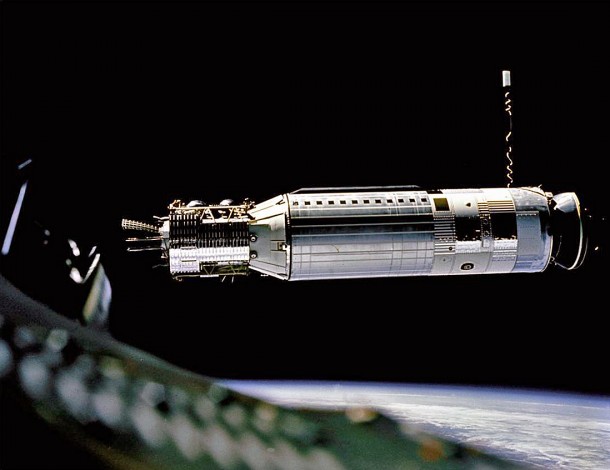

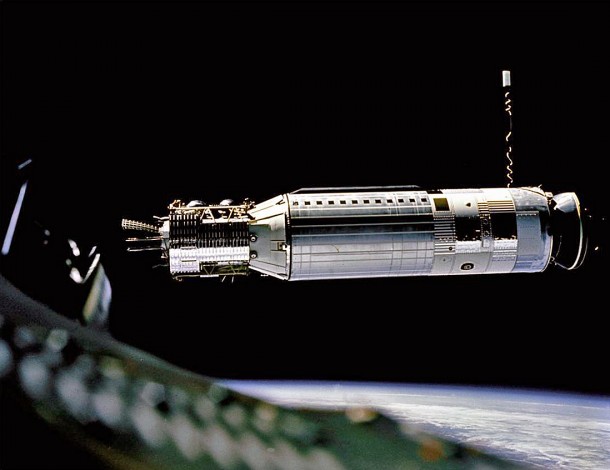

Forty-nine years ago this month, the crew of Gemini VIII successfully regained control of their tumbling spacecraft following failure of an attitude control thruster. The incident marked the first life-threatening on-orbit emergency and resulting mission abort in the history of Amercian manned spaceflight.

Gemini VIII was the sixth manned mission of the Gemini Program. The primary mission objective was to rendezvous and dock with an orbiting Agena Target Vehicle (ATV). Successful accomplishment of this objective was seen as a vital step in the Nation’s quest for landing men on the Moon.

The Gemini VIII crew consisted of Command Pilot Neil A. Armstrong and Pilot USAF Major David R. Scott. Both were space rookies. To them would go both the honor of achieving the first successful docking in orbit as well as the challenge of dealing with the first life and death space emergency involving an American spacecraft.

Gemini VIII lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 16:41:02 UTC on Wednesday, 16 March 1966. The crew’s job was to chase, rendezvous and then physically dock with an Agena that had been launched 101 minutes earlier. The Agena successfully achieved orbit and waited for Gemini VIII in a 161-nm circular Earth orbit.

It took just under six (6) hours for Armstrong and Scott to catch-up and rendezvous with the Agena. The crew then kept station with the target vehicle for a period of about 36 minutes. Having assured themselves that all was well with the Agena, the world’s first successful docking was achieved at a Gemini mission elasped time of 6 hours and 33 minutes.

Once the reality of the historic docking sank in, a delayed cheer erupted from the NASA and contractor team at Mission Control in Houston, Texas. Despite the complex orbital mechanics and delicate timing involved, Armstrong and Scott had actually made it look easy. Unfortunately, things were about to change with an alarming suddeness.

As the Gemini crew maneuvered the Gemini-Agena stack, their instruments indicated that they were in an uncommanded 30-degree roll. Using the Gemini’s Orbital Attiude and Maneuvering System (OAMS), Armstrong was able to arrest the rolling motion. However, once he let off the restoring thruster action, the combined vehicle began rolling again.

The crew’s next action was to turn off the Agena’s systems. The errant motion subsided. Several minutes elapsed with the control problem seemingly solved. Suddenly, the uncommanded motion of the still-docked pair started again. The crew noticed that the Gemini’s OAMS was down to 30% fuel. Could the problem be with the Gemini spacecraft and not the Agena?

The crew jettisoned the Agena. That didn’t help matters. The Gemini was now tumbling end over end at almost one revolution per second. The violent motion made it difficult for the astronauts to focus on the instrument panel. Worse yet, they were in danger of losing consciousness.

Left with no other alternative, Armstrong shut down his OAMS and activated the Reentry Control System reaction control system (RCS) in a desperate attempt to stop the dizzying tumble. The motion began to subside. Finally, Armstrong was able to bring the spacecraft under control.

That was the good news. The bad news for the crew of Gemini VIII was that the rest of the mission would now have to be aborted. Mission rules dictated that such would be the case if the RCS was activated on-orbit. There had to be enough fuel left for reentry and Gemini VIII had just enough to get back home safely.

Gemini VIII splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean 4,320 nm east of Okinawa. Mission elapsed time was 10 hours, 41 minutes and 26 seconds. Spacecraft and crew were safely recovered by the USS Leonard F. Mason.

In the aftermath of Gemini VIII, it was discovered that OAMS Thruster No. 8 had failed in the ON position. The probable cause was an electrical short. In addition, the design of the OAMS was such that even when a thruster was switched off, power could still flow to it. That design oversight was fixed so that subsequent Gemini missions would not be threatened by a reoccurence of the Gemini VIII anomaly.

Neil Armstrong and David Scott met their goliath in orbit and defeated the beast. Armstrong received a quality increase for his efforts on Gemini VIII while Scott was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Both men were awared the NASA Exceptional Service Medal.

More significantly, their deft handling of the Gemini VIII emergency elevated both Armstrong and Scott within the ranks of the astronaut corps. Indeed, each man would ultimately land on the Moon and serve as mission commander in doing so; Neil Armstrong on Apollo 11 and David Scott on Apollo 15.

Seven years ago this month, a United States Navy STANDARD Missile SM-3 Block IA interceptor engaged and destroyed a defunct NRO satellite at an altitude of 133 nautical miles. The relative velocity at intercept was in excess of 22,000 mph.

The United States Navy/Raytheon Missile Systems SM-3 (RIM-161) is the sea-based arm of the Missile Defense Agency’s Ballistic Missile Defense System (BMDS). The 3-stage missile carries a Kinetic Warhead (KW) that provides an exoatmospheric hit-to-kill capability.

In order to ensure a lethal hit, the SM-3 KW guides to a specific aimpoint on the target’s airframe. The ability to reliably do so has been impressively demonstrated in a series of intercept flight tests that began in 2002.

SM-3 rounds are launched from the MK-41 Vertical Launcher System (VLS) aboard United States Navy cruisers and destroyers. The at-sea basing concept provides for a high degree of operational flexibility in the ballistic missile intercept mission.

The Lockheed Martin-built USA-193 was launched on a classified mission from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB) at 2100 UTC on Thursday, 14 December 2006. However, shortly after reaching orbit, contact with the 5,000-lb defense satellite was lost.

By January 2008, USA-193′s orbit had decayed to such an extent that its reentry back into the earth’s atmosphere appeared imminent. Such events raise concerns for the safety of those on Earth who reside within the debris impact footprint. However, there was an additional concern in the case of USA-193. The satellite still had about 1,000-lbs of hydrazine onboard.

Should the USA-193 hydrazine tank survive reentry, those living in the impact area would be exposed to a highly toxic cloud of the volatile substance. Officials concluded that the safest thing to do was to destroy the satellite before it reentered the atmosphere.

On Thursday, 21 February 2008, the USS Lake Erie was on station in the Pacific Ocean somewhere west of Hawaii. The US Navy cruiser fired a single SM-3 interceptor at 0326 UTC. Minutes later, the missile’s KW took out the satellite and dispersed its hydrazine load into space. Mission accomplished!

In the aftermath of the satellite take-down, Russia and others predictably accused the United States of using the USA-193 hydrazine issue as an excuse to demonstrate SM-3′s anti-satellite capability. While such capability was indeed demonstrated, noteworthy is the fact that all systems modified to execute the satellite intercept have subsequently been returned to a ballistic missile defense posture.

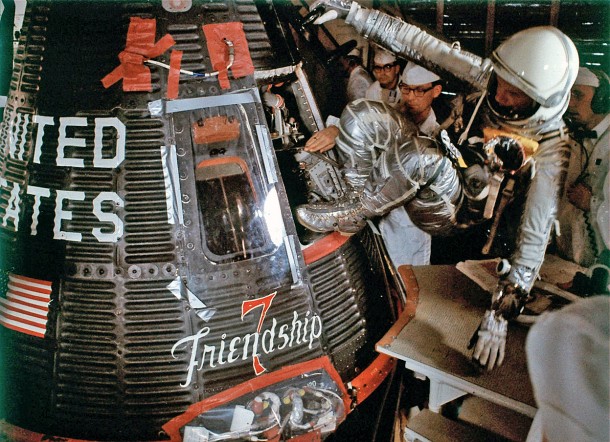

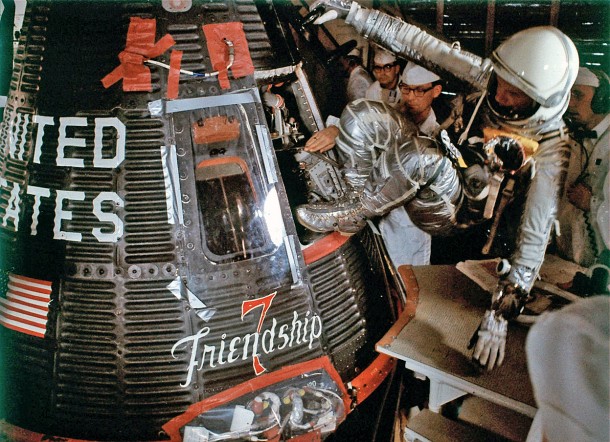

Fifty-three years ago this week, Project Mercury Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn’s spacecraft name and mission call sign was Friendship 7.

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 14 at 14:47:39 UTC on Tuesday, 20 February 1962. It was the first time that the Atlas LV-3B booster was used for a manned spaceflight.

Three-hundred and twenty seconds after lift-off, Friendship 7 achieved an elliptical orbit measuring 143 nm (apogee) by 86 nm (perigee). Orbital inclination and period were 32.5 degrees and 88.5 minutes, respectively.

The most compelling moments in the United States’ first manned orbital mission centered around a sensor indication that Glenn’s heatshield and landing bag had become loose at the beginning of his second orbit. If true, Glenn would be incinerated during entry.

Concern for Glenn’s welfare persisted for the remainder of the flight and a decision was made to retain his retro package following completion of the retro-fire sequence. It was hoped that the 3 straps securing the retro package would also hold the heatshield in place.

During Glenn’s return to the atmosphere, both the spent retro package and its restraining straps melted in the searing heat of re-entry. Glenn saw chunks of flaming debris passing by his spacecraft window. At one point he radioed, “That’s a real fireball outside”.

Happily, the spacecraft’s heatshield held during entry and the landing bag deployed nominally. There had never really been a problem. The sensor indication was found to be false.

Friendship 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at a point 432 nm east of Cape Canaveral at 19:43:02 UTC. John Glenn had orbited the Earth 3 times during a mission which lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds. Within short order, spacecraft and astronaut were successfully recovered aboard the USS Noa.

John Glenn became a national hero in the aftermath of his 3-orbit mission aboard Friendship 7. It seemed that just about every newspaper page in the days following his flight carried some sort of story about his historic fete. Indeed, it is difficult for those not around back in 1962 to fully comprehend the immensity of Glenn’s flight in terms of what it meant to the United States.

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. will turn 94 on 18 July 2015. His trusty Friendship 7 spacecraft is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

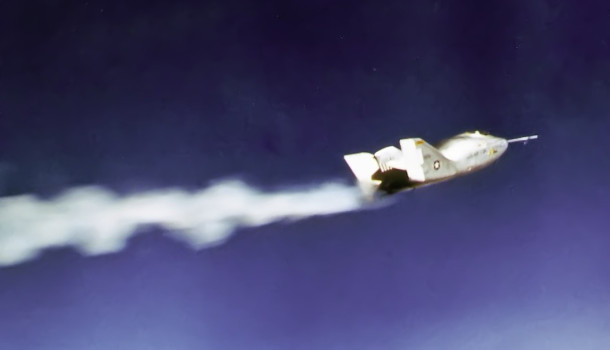

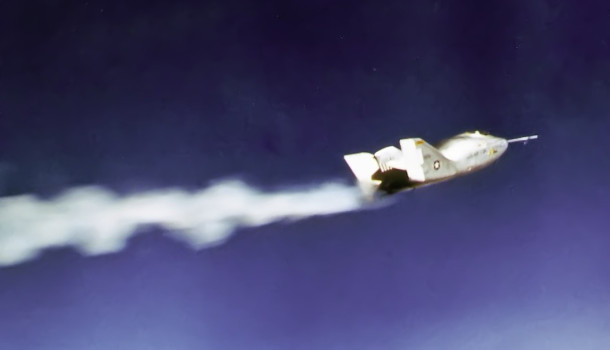

Fifty-nine years ago this month, the USAF/North American X-10 experimental flight research vehicle achieved a maximum speed of Mach 2.05 during its 19th test flight. The mark established a new speed record for turbojet-powered aircraft.

The precedent set by the Nazi V-1 and V-2 Vergeltungswaffen (Vengeance Weapons) in World War II motivated the United States to launch a post-war effort to develop a strategic range-capable missile capability. The earliest example in this regard was the USAF/North American Navaho (SM-64).

Known as Project MX-770, the Navaho was developmental effort to deliver a nuclear warhead at a range of 5,500 nm. The Navaho configuration consisted of a rocket-powered first stage and a winged second stage utilizing ramjet propulsion. The second stage was designed to cruise at Mach 2.75.

The X-10 was a testbed version of the Navaho second stage. The X-10 measured 66 feet in length, sported a wingspan of 28 feet and had a GTOW of 42,000 lbs. The sleek aircraft was powered by twin Westinghouse J40-WE-1 turbojets. These powerplants burned JP-4 and were each rated at 10,900 lbs of sea level thrust in full afterburner.

The X-10 was a double sonic-capable aircraft. It had an unrefueled range of 850 miles and a maximum altitude capability of 44,800 feet.

The X-10 vehicle flight surfaces included elevons for pitch and roll control and twin rudders for yaw control. Canard surfaces were employed for pitch trim. The aircraft was designed to take-off, maneuver and land under external control provided by either airborne or ground-based assets.

A total of thirteen (13) X-10 airframes were constructed by North American. Flight testing originated at the Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC), Edwards Air Force Base, California and later moved to the Air Force Missile Test Center (AFMTC) at Cape Canaveral in Florida.

There was a total of twenty-seven (27) X-10 flight tests. Fifteen (15) flight tests took place at the AFFTC between October of 1953 and March of 1955. Twelve (12) flight tests were conducted at the AFMTC between August 1955 and November 1956.

X-10 airframe GM-52-1 (GM-52-2 pictured above) achieved the highest speed of the type’s flight test series. On Wednesday, 29 February 1956, the aircraft recorded a peak Mach Number of 2.05 during the 19th flight test of the X-10 Program. At the time, this was a record for turbojet-powered aircraft. The record mission originated from and recovered to the runways at AFMTC.

While the X-10 Program produced a wealth of aerodynamic, structural, flight control and flight performance data, test vehicle attrition was extremely high. The lone X-10 to survive flight testing was airframe GM-19307. It is currently on display at the Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Forty years ago this week, a USAF/McDonnell-Douglas F-15A Eagle Air Superiority Fighter zoomed to an altitude of 30 km (98,425 feet) in an elapsed time of 207.8 seconds from brake release. The pilot for the record-breaking mission was USAF Major Roger Smith.

Operation Streak Eagle was a mid-1970′s effort by the United States Air Force to set eight (8) separate time-to-climb records using the then-new McDonnell-Douglas F-15 Air Superiority Fighter. These record-setting flights originated from Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Starting on Thursday, 16 January 1975, the 19th pre-production F-15 Eagle aircraft (S/N 72-0119) was used to establish the following time-to-climb records during Operation Streak Eagle:

3 km, 16 January 1975, 27.57 seconds, Major Roger Smith

6 km, 16 January 1975, 39.33 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

9 km, 16 January 1975, 48.86 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

12 km, 16 January 1975, 59.38 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

15 km, 16 January 1975, 77.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

20 km, 19 January 1975, 122.94 seconds, Major Roger Smith

25 km, 26 January 1975, 161.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

The eighth and final time-to-climb record attempt of Operation Streak Eagle took place on Saturday, 01 February 1975. The goal was to set a new time-to-climb record to 30 km. The pilot was required to wear a full pressure suit for this mission.

At a gross take-off weight of 31,908 pounds, the Streak Eagle aircraft had a thrust-to-weight ratio in excess of 1.4. The aircraft was restrained via a hold-down device as the two Pratt and Whitney F100 turbofan engines were spooled-up to full afterburner.

Following hold-down and brake release, the Streak Eagle quickly accelerated during a low level transition following take-off. At Mach 0.65, Smith pulled the aircraft into a 2.5-g Immelman. The Streak Eagle completed this maneuver 56 seconds from brake release at Mach 1.1 and 9.75 km. Rolling the aircraft upright, Smith continued to accelerate the Streak Eagle in a shallow climb.

At an elapsed time of 151 seconds and with the aircraft at Mach 2.2 and 11.3 km, Smith executed a 4-g pull to a 60-degree zoom climb. The Steak Eagle passed through 30 km at Mach 0.7 in an elapsed time of 207.8 seconds. The apex of the zoom trajectory was about 31.4 km. With a new record in hand, Smith uneventfully recovered the aircraft to Grand Forks AFB.

Operation Streak Eagle ended with the capturing of the 30 km time-to-climb record. In December 1980, the aircraft was retired to the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. It is currently held in storage at the Museum and no longer on public display.

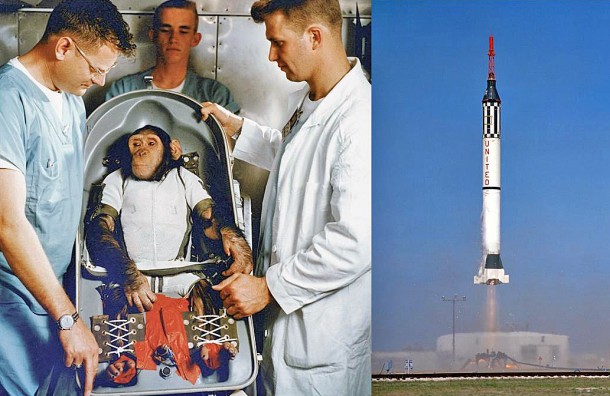

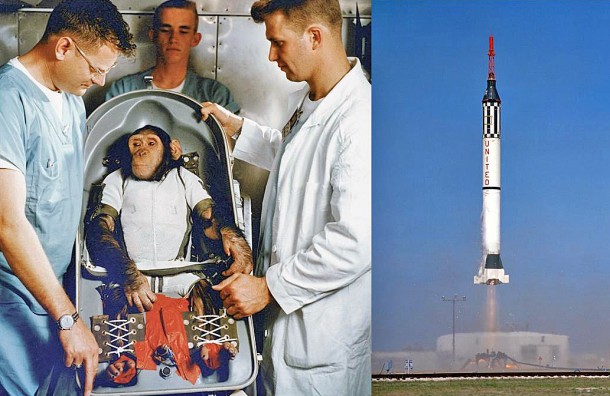

Fifty-four years ago this month, NASA successfully conducted a critical flight test of the space agency’s Mercury-Redstone launch vehicle which helped clear the way for the United States’ first manned suborbital spaceflight. Riding the diminutive Mercury spacecraft into space and back was a 44-month old male chimpanzee by the name of HAM.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. Simply put, Mercury helped us learn how to fly astronauts in space and return them safely to earth. A total of six (6) manned missions were flown between May of 1961 and May of 1963. The first two (2) flights were suborbital shots while the final four (4) flights were full orbital missions. All were successful.

The Mercury spacecraft weighed about 3,000 lbs, measured 9.5-ft in length and had a base diameter of 6.5-ft. Though diminutive, the vehicle contained all the systems required for manned spaceflight. Primary systems included guidance, navigation and control, environmental control, communications, launch abort, retro package, heatshield, and recovery.

Mercury spacecraft launch vehicles included the Redstone and Atlas missiles. Both were originally developed as weapon systems and therefore had to be man-rated for the Mercury application. Redstone, an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM), was the booster for Mercury suborbital flights. Atlas, an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), was used for orbital missions.

Early Mercury-Redstone (MR) flight tests did not go particularly well. The subject missions, MR-1 and MR-1A, were engineering test and development flight tests flown with the intent of man-rating both the converted launch vehicle and new manned spacecraft.

MR-1 hardly flew at all in that its rocket motor shut down just after lift-off. After soaring to the lofty altitude of 4-inches, the vehicle miraculously settled back on the launch pad without toppling over and detonating its full load of propellants. MR-1A flew, but owing to higher-than-predicted acceleration, went much higher and farther than planned. Nonetheless, MR flight testing continued in earnest.

The objectives of MR-2 were to verify (1) that the fixes made to correct MR-1 and MR-1A deficiencies indeed worked and (2) proper operation of a bevy of untested systems as well. These systems included environmental control, attitude stabilization, retro-propulsion, voice communications, closed-loop abort sensing and landing shock attenuation. Moreover, MR-2 would carry a live biological payload (LBP).

A 44-month old male chimpanzee was selected as the LBP. He was named HAM in honor of the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center where the primate trained. HAM was taught to pull several levers in response to external stimuli. He received a banana pellet as a reward for responding properly and a mild electric shock as punishment for incorrect responses. HAM wore a light-weight flight suit and was enclosed within a special biopack during spaceflight.

On Tuesday, 31 January 1961, MR-2 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-5 at 16:55 UTC. Within one minute of flight, it became obvious to Mission Control that the Redstone was again over-accelerating. Thus, HAM was going to see higher-than-planned loads at burnout and during reentry. Additionally, his trajectory would take him higher and farther downrange than planned. Nevertheless, HAM kept working at his lever-pulling tasks.

The Redstone burnout velocity was 5,867 mph rather than the expected 4,400 mph. This resulted in an apogee of 137 nm (100 nm planned) and a range of 367 nm (252 nm predicted). HAM endured 14.7 g’s during entry; well above the 12 g’s planned. Total flight duration was 16.5 minutes; several minutes longer than planned.

Chillingly, HAM’s Mercury spacecraft experienced a precipitous drop in cabin pressure from 5.5 psig to 1 psig just after burnout. High flight vibrations had caused the air inlet snorkel valve to open and dump cabin pressure. HAM was both unaware of and unaffected by this anomaly since he was busy pulling levers within the safety of his biopack.

HAM’s Mercury spacecraft splashed-down at 17:12 UTC about 52 nm from the nearest recovery ship. Within 30 minutes, a P2V search aircraft had spotted HAM’s spacecraft (now spaceboat) floating in an upright position. However, by the time rescue helicopters arrived, the Mercury spacecraft was found floating on its side and taking on sea water.

Apparently, a combination of impact damage to the spacecraft’s pressure bulkhead and the open air inlet snorkel valve resulted in HAM’s spacecraft taking on roughly 800 lbs of sea water. Further, heavy ocean wave action had really hammered HAM and the Mercury spacecraft. The latter having had its beryllium heatshield torn away and lost in the process.

Fortunately, one of the Navy rescue helicopters was able to retrieve the waterlogged spacecraft and deposit it safely on the deck of the USS Donner. In short order, HAM was extracted from the Mercury spacecraft. Despite the high stress of the day’s spaceflight and recovery, HAM looked pretty good. For his efforts, HAM received an apple and an orange-half.

While the MR-2 was judged to be a success, one more flight would eventually be flown to verify that the Redstone’s over-acceleration problem was fixed. That flight, MR-BD (Mercury-Redstone Booster Development) took place on Friday, 24 March 1961. Forty-two (42) days later USN Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became America’s first astronaut.

MR-2 was HAM’s first and only spaceflight experience. He quietly lived the next 17 years as a resident of the National Zoo in Washington, DC. His last 2 years were spent living at a North Carolina zoo. On Monday, 19 January 1983, HAM passed away at the age of 26. HAM is interred at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in Alamogordo, NM.

Fifty-seven years ago this month, a XSM-64 Navaho G-26 flight test vehicle flew 1,075 miles in 40 minutes at a sustained speed of Mach 2.8. It was the 8th flight test of the ill-fated Navaho Program.

The post-World War II era saw the development of a myriad of missile weapons systems. Perhaps the most influential and enigmatic of these systems was the Navaho missile.

Navaho was intended as a supersonic, nuclear-capable, strategic weapon system. It consisted of two (2) stages. The first stage was rocket-powered while the second stage utilized ramjet propulsion. The aircraft-like second stage was configured with a high lift-to-drag airframe in order to achieve strategic reach.

While there were a number of antecedents dating back to 1946, the Navaho Program really began in 1950 as Weapon System 104A. The requirements included a range of 5,500 miles, a minimum cruise speed of Mach 3 and a minimum cruise altitude of 60,000 feet. The payload included an ordnance load of 7,000 pounds delivered within a CEP of 1,500 feet.

North American Aviation (NAA) proposed a 3-phase development plan for WS-104A. Phase 1 involved testing of the missile alone (the X-10) up to Mach 2. Phase 2 covered the testing of the two-stage launch vehicle (the G-26) up to Mach 2.75 and a range of 1,500 miles. Phase 3 would be the ultimate near-production vehicle (the G-38). Only Phase 1 and Phase 2 testing took place.

The Navaho missile-booster vehicle measured 84 feet in length and weighed about 135,000 pounds at lift-off. The launch weight for the booster was 75,000 pounds; most of which was due to the alcohol and LOX propellants. The missile empty weight was 24,000 pounds.

On Friday, 10 January 1958, Navaho G-26 No. 9 (54-3098) lifted-off from LC-9 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Climbing out under 240,000 pounds of thrust from its dual Rocketdyne XLR71-NA-1 rocket motors, missile-booster separation occurred at Mach 3.15 and 73,000 feet. Following air-start and take-over of twin Wright XRJ47-W-5 ramjets, generating a combined thrust of 16,000 pounds, the Navaho missile initiated a near triple-sonic cruise toward the Puerto Rico target area.

As the Navaho missile approached the environs of Puerto Rico, the vehicle was commanded to initiate a sweeping right-hand turn back towards the Cape. Unfortunately, the right intake experienced an unstart and a concomitant, asymmetric loss of thrust. Underpowered and without a restart capability, the vehicle was subsequently commanded to execute a dive into the Atlantic.

Flight No. 8, although only partially successful, flew longer and farther than any Navaho flight test vehicle. Only G-26 Flight No. 6 flew faster (Mach 3.5).

Although three (3) flights would follow G-26 Flight No. 8, all would suffer failure of one kind or another. In point of fact, the Navaho Program had been canceled on Saturday, 13 July 1957. The final six (6) Navaho flights were simply an attempt to extract the most from the remaining missile-booster rounds. Over 15,000 NAA employees lost their jobs the day Navaho died.

Navaho was cancelled primarily due to the ascendancy of the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). Very simply, an ICBM could deliver nuclear ordnance farther, faster and more accurately than a winged, unstealthy strategic missile. Navaho’s relatively numerous technical issues and programmatic delays simply served to drive the final nail into a long-prepared coffin.

While few today remember or even know of the Navaho Program, its technology has had a profound influence on all manner of aerospace vehicles up to the present day. Interestingly, the Space Shuttle launch vehicle concept bears a strong resemblance to the Navaho missile-booster combination. That is, a winged flight vehicle mounted asymmetrically on a longer boost vehicle.