Twenty-nine years ago today, the Space Shuttle Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base to successfully conclude the fourth orbital mission of the Space Transportation System. Columbia’s return to earth added a special touch to the celebration of America’s 207th birthday.

STS-4 was NASA’s fourth Space Shuttle mission in the first fourteen months of Shuttle orbital flight operations. The two-man crew consisted of Commander Thomas K. Mattingly, Jr. and Pilot Henry W. Hartsfield who were both making their first Shuttle orbital mission. STS-4 marked the last time that a Shuttle would fly with a crew of just two.

STS-4 was launched from Cape Canaveral’s LC-39A on Sunday, 27 June 1982. Lift-off was exactly on-time at 15:00:00 UTC. Interestingly, this would be the only occasion in which a Space Shuttle would launch precisely on-time. The Columbia weighed a hefty 241,664 lbs at launch.

Mattingly and Hartsfield spent a little over seven (7) days orbiting the Earth in Columbia. The orbiter’s cargo consisted of the first Getaway Special payloads and a classified US Air Force payload of two missile launch-detection systems. In addition, a Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES) and the Mono-Disperse Latex Reactor (MLR) were flown for a second time.

The Columbia crew conducted a lightning survey using manual cameras and several medical experiments. Mattingly and Hartsfield also maneuvered the Induced Environment Contamination Monitor (IECM) using the Orbiter’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS). The IECM was used to obtain information on gases and particles released by Columbia in flight.

On Sunday, 04 July 1982, retro-fire started Columbia on its way back to Earth. Touchdown occurred on Edwards Runway 22 at 16:09:31 UTC. This landing marked the first time that an Orbiter landed on a concrete runway. (All three previous missions had landed on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards.) Columbia made 112 complete orbits and traveled 2,537,196 nautical miles during STS-4.

The Space Shuttle was declared “operational” with the successful conduct of the first four (4) shuttle missions. President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan even greeted the returning STS-4 flight crew on the tarmac. However, as history has since taught us, manned spaceflight still comes with a level of risk and danger that exceeds that of military and commercial aircraft operations. It will be some time before a manned space vehicle is declared operational in the desired sense.

Fifty-three years ago this week, the United States Army Nike Hercules air defense missile system was first deployed in the continental United States. The second-generation surface-to-air missile was designed to intercept and destroy hostile ballistic missiles.

The Nike Program was a United States Army project to develop a missile capable of defending high priority military assets and population centers from attack by Soviet strategic bombers. Named for the Greek goddess of victory, the Nike Program began in 1945. The industrial consortium of Bell Laboratories, Western Electric, Hercules and Douglas Aircraft developed, tested and fielded Nike for the Army.

Nike Ajax (MIM-3) was the first defensive missile system to attain operational status under the Nike Program. The two-stage, surface-launched interceptor initially entered service at Fort Meade, Maryland in December of 1953. A total of 240 Nike Ajax launch sites were eventually established throughout CONUS. The primary assets protected were metropolitan areas, long-range bomber bases, nuclear plants and ICBM sites.

Nike Ajax consisted of a solid-fueled first stage (59,000 lbs thrust) and a liquid-fueled second stage (2,600 lbs thrust). The launch vehicle measured nearly 34 feet in length and had a ignition weight of 2,460 lbs. The second stage was 21 feet long, had a maximum diameter of 12 inches and weighed 1,150 lbs fully loaded. The type’s maximum speed, altitude and range were 1,679 mph, 70,000 feet and 21.6 nautical miles, respectively.

The Nike Hercules (MIM-14) was the successor to the Nike Ajax. It featured all-solid propulsion and much higher thrust levels. The first stage was rated at 220,000 lbs of thrust while that of the second stage was 10,000 lbs. The Nike Hercules airframe was significantly larger than its predecessor. The launch vehicle measured 41 feet in length and weighed 10,700 lbs at ignition. Second stage length and ignition weight were 26.8 feet and 5,520 lbs, respectively.

Nike Hercules kinematic performance was quite impressive. The respective top speed, altitude and range were 3,000 mph, 150,000 feet and 76 nautical miles. This level of performance allowed the vehicle to be used for the ballistic missile intercept mission. Most Nike Hercules missiles carried a nuclear warhead with a yield of 20 kilotons.

The first operational Nike Hercules systems were deployed to the Chicago, Philadelphia and New York localities on Monday, 30 June 1958. By 1963, fully 134 Nike Hercules batteries were deployed throughout CONUS. These systems remained in the United States missile arsenal until 1974. The exceptions were batteries located in Alaska and Florida which remained in active service until the 1978-79 time period.

Like Nike Ajax before it, Nike Hercules had a successor. It was originally known as Nike Zeus and then Nike-X. This Nike variant was designed for intercepting enemy ICBM’s that were targeted for American soil. The vehicle went through a number of iterations before a final solution was achieved. Known as Spartan, this missile was what we would refer to today as a mid-course interceptor.

In companionship with a SPRINT terminal phase interceptor, Spartan formed the Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System. The American missile defense system was impressive enough to the Soviet Union that the communist country signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty 3 years before Safeguard’s deployment. Though operational for a mere 3 months, Safeguard was depostured in 1975. This action brought to a close a 30-year period in which the Nike Program was a major player in American missile defense.

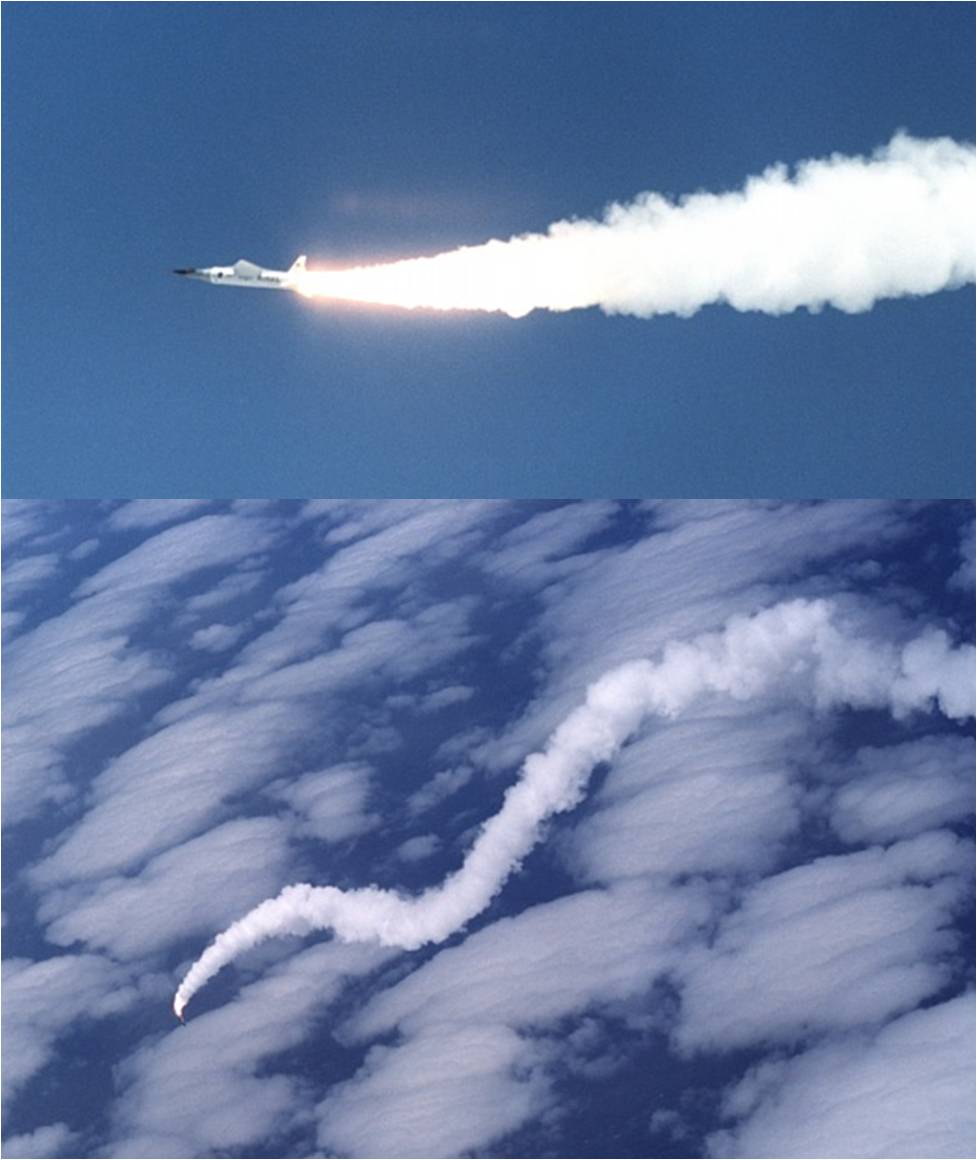

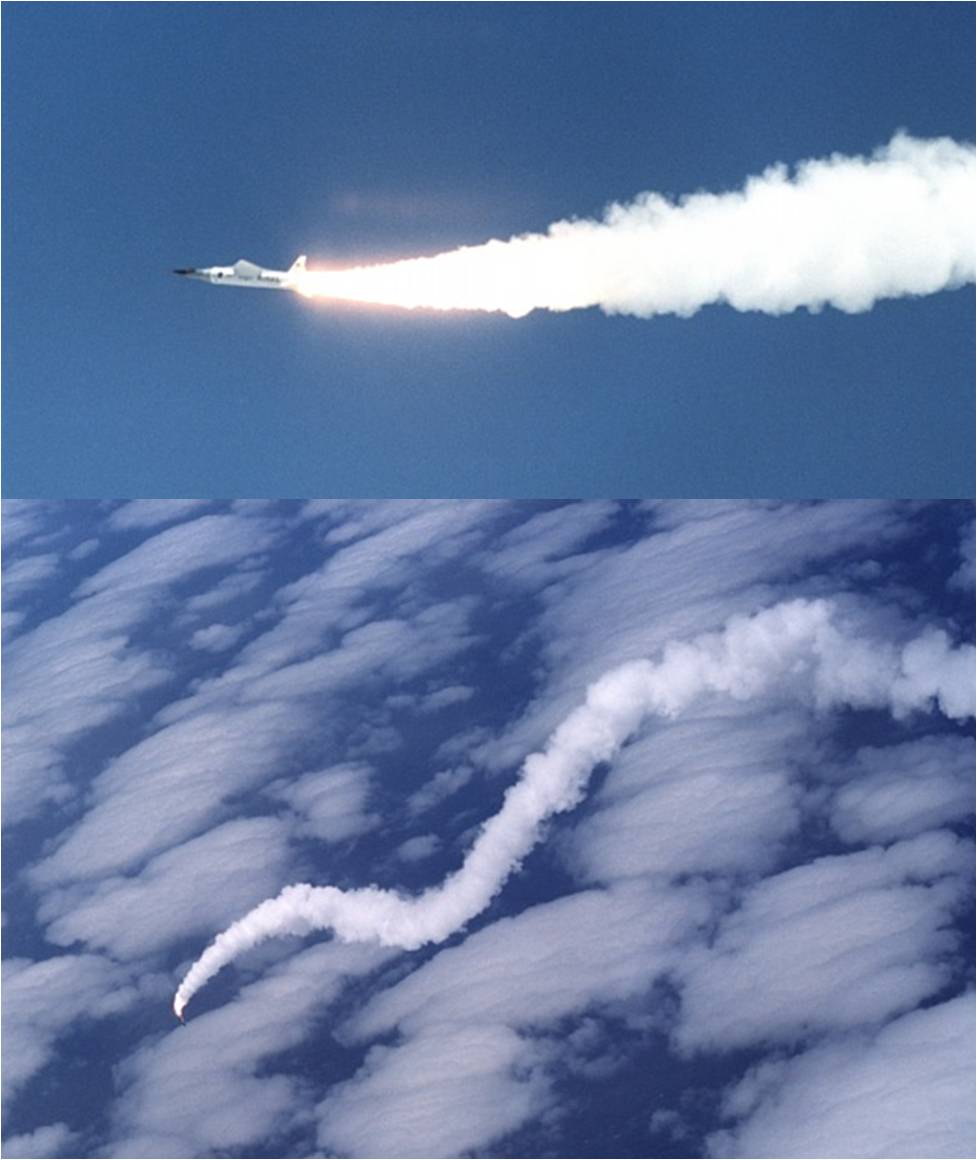

Ten years ago this month, the first NASA X-43A airframe-integrated scramjet flight research vehicle was launched from a B-52 carrier aircraft high over the Pacific Ocean. The inaugural mission of the HYPER-X Flight Project came to an abrupt end when the launch vehicle departed controlled flight while passing through Mach 1.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X (HX). The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The first flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 02 June 2001. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 19:28 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 20:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership at 24,000 feet. Following a 5.2 second free fall, the rocket motor lit and the HXLV started to head upstairs. Disaster struck just as the vehicle accelerated through Mach 1. That’s when the rudder locked-up. The launch vehicle then pitched, yawed and rolled wildly as it departed controlled flight. Control surfaces were shed and the wing was ripped away. The HXRV was torn from the booster and tumbled away in a lifeless state. All airframe debris fell into the cold Pacific Ocean far below.

The mishap investigation board concluded that no single factor caused the loss of HX Flight No. 1. Failure occurred because the vehicle’s flight control system design was deficient in a number of simulation modeling areas. The result was that system operating margins were overestimated. Modeling inaccuracies were identified primarily in the areas of fin system actuation, vehicle aerodynamics, mass properties and parameter uncertainties. The flight mishap could only be reproduced when all of the modeling inaccuracies with uncertainty variations were incorporated in the analysis.

The X-43A Return-to-Flight effort took almost 3 years. Happily, the HYPER-X Program hit paydirt twice in 2004. On Saturday, 27 March 2004, HX Flight No. 2 achieved scramjet operation at Mach 6.83 (almost 5,000 mph). This historic accomplishment was eclipsed by even greater success on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. Indeed, HX Flight No. 3 achieved sustained scramjet operation at Mach 9.68 (nearly 7,000 mph).

The historic achievements of the HYPER-X Program went largely unnoticed by the aerospace industry and the general public. For its part, NASA did not do a very good job of helping people understand the immensity of what was accomplished. Even the NASA Administrator appeared different to the scramjet program. While he attended an X-Prize flight by Scaled-Composites’ SpaceShipOne right up the street at the Mojave Spaceport, he did not see fit to attend either of that year’s historic scramjet flights that originated right down the street at Edwards Air Force base.

However, it was the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-107 in February of 2003 that doomed HX even before the program’s first successful flight. Everything changed for NASA when Columbia and its crew was lost. The agency’s overriding focus and meager financial resources went into the Shuttle Return-to-Flight effort. NASA’s aeronautical and access-to-space arms were especially hard hit.

If timing is everything as some insist, then the HYPER-X Program was really the victim of bad timing. It is both intriguing and distressing to ponder what would have been the case if HX Flight No. 1 had been successful. The likely answer is that at least one of the anticipated follow-on scramjet flight research programs (i.e., X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D) would have been developed and flown. Thanks to Murphy’s ubiquitous influence, we’ll never know.

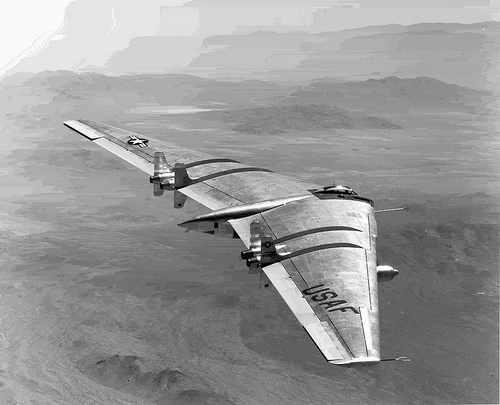

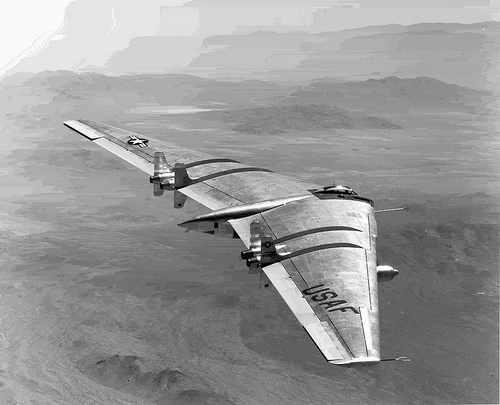

Sixty-three years ago this month, the USAF/Northrop YB-49 Flying Wing came apart during a test flight that originated at Muroc Air Force Base. Among the five crew members who perished in the aviation mishap was famed test pilot USAF Captain Glen W. Edwards.

The USAF/Northrop YB-49 heavy bomber prototype first flew in October of 1947. The aircraft was a jet-powered derivative of the propeller-driven XB-35. Both of these legendary aircraft were flying wing designs pioneered by visionary aircraft designer Jack Northrop.

Traditionally, interest in a flying wing aircraft stems from its inherently-high lift, low drag and hence high lift-to-drag ratio characteristics. These attributes make a flying wing ideal for the strategic bombing mission where large payloads must be carried long distances to the target. In addition, the type’s low profile and swept wings contributed to its low radar cross-section.

The same configurational features that give flying wing aircraft favorable performance also present stability and control issues and adverse handling qualities. The lack of a traditional empenage requires that all flight controls be placed on the wing itself. This leads to significant aerodynamic coupling that affects aircraft pitch, yaw and roll motion.

The YB-49 had a wing span of 172 feet, a length of 53 feet and a height of 15 feet. Gross take-off weight was approximately 194,000 lbs. Fuel accounted for roughly 106,000 lbs of that total. Power was supplied by eight (8) Allison/General Electric J35-A-5 turbojets. Each of these early-generation powerplants was rated at a mere 4,000 lbs of sea level thrust.

The YB-49 design performance included a maximum speed of 495 mph, a service ceiling of 45,700 feet and a maximum range of 8,668 nautical miles. The aircraft was designed to carry a maximum bomb load of 32,000 lbs. The strategic bombing mission would be flown by a crew of seven (7) including pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier and gunners.

A pair of XB-35 airframes were modified to the YB-49 configuration. Ship No. 1 (S/N 42-102367) first took to the air on Tuesday, 21 October 1947. The maiden flight of Ship No. 2 (S/N 42-102368) occurred on Tuesday, 13 January 1948. Both flights originated from Hawthorne Airport and recovered at Muroc Air Force Base.

Flight testing of the YB-49 quickly confirmed the type’s performance promise. Demonstrated performance included a top speed of 520 mph and a maximum altitude of 42,000 feet. On Monday, April 26, 1948. On that date, the aircraft remained aloft for 9.5 hours, of which 6.5 hours were flown at an altitude of 40,000 feet.

The low point in YB-49 flight testing came on Saturday, 05 June 1948. On that fateful day, YB-49 Ship No. 2 crashed to destruction in the Mojave Desert northwest of Muroc Air Force Base. The entire crew of five (5) perished in the mishap. These crew members included Major Daniel N. Forbes (pilot), Captain Glen W. Edwards (co-pilot), Lt. Edward L. Swindell (flight engineer), Clare E. Lesser (observer) and Charles H. LaFountain (observer).

The cause of the YB-49 mishap was never fully determined. In descending from 40,000 feet following a test mission, the aircraft somehow exceeded its structural limit. The outer wing panels failed and the rest of the aircraft tumbled out of control, struck the ground inverted and immediately fireballed. Whether the incident was related to wing stall, spin or some such other flight control issue will never be definitively known.

YB-49 Ship No. 1 continued to fly after the loss of its stable mate. However, it too met an unkind fate. On Wednesday, 15 March 1950, the aircraft was declared a total loss following a non-fatal high-speed taxiing mishap. Several months later, all of Northrop’s flying wing contracts with the government were unexpectedly cancelled. Incredibly, the Wizards of the Beltway ultimately ordered that all Northrop-produced flying wing variants be cut-up for scrap.

Despite its performance, the YB-49 was too far ahead of its time. The aircraft did not exhibit good handling qualities and thus was not a good bombing platform. It needed the type of computer-based, multiply-redundant autopilot that is standard equipment on today’s aircraft.

Happily, the performance merits of the flying wing concept would be fully exploited with the introduction of the USAF/Northrop B-2 Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB). This aircraft first flew on Monday, 17 July 1989. Its subsequent success is now history. A host of new technologies converged to finally made the flying wing concept viable. Not the least of which is the aircraft’s multiply-redundant flight control system.

Finally, we note that 30-year old Captain Glen W. Edwards was a rising star in military flight test circles at the time of his death. In tribute to his aviation skills and in memory of a life cut short, Muroc Air Force Base was officially renamed on Tuesday, 05 December 1950. Since that day, it has been known as Edwards Air Force Base.

Sixty-two years this week, the No. 2 USAF/Northrop X-4 experimental flight research aircraft took to the air for the first time. The flight of the second X-4 prototype originated from and recovered at Muroc Air Force Base, California.

The USAF/Northrop X-4 was an early X-plane designed to explore the flight characteristics of a swept-wing, tailless aircraft in transonic flight. It came into being as a result of recent Air Force studies which indicated that a tailless configuration might alleviate or eliminate instability issues associated with supersonic flight. The X-4’s external configuration was similar to that of the German Me163 Komet and the British De Havilland DH.108 Swallow.

The USAF contracted with the Northrop Aircraft Company in June of 1946 to construct and perform initial flight testing of two (2) X-4 aircraft. Northrop received the sole-source contract principally because of the company’s vast experience with flying-wing aircraft. Notable examples include the N-1M, XP-79B, XP-56 and the fabled B-35 heavy bomber.

The X-4 was a physically small airplane. As such, it received the nickname Bantam. It measured 23.25-feet in length and had a wing span of 26.75-feet. The wing leading edge sweep angle was 40.5-degrees. Gross take-off weight was 7,820 lbs. Power was provided by a pair of Westinghouse J30-WE-9 non-afterburning turbojets. Each powerplant had a sea level thrust rating of a paltry 1,600-lbs.

Due to the absence of a horizontal tail and an associated elevator, the X-4 was configured with wing-mounted elevons (combined elevator and aileron). These surfaces provided both pitch and roll control. The type’s split trailing edge flaps were used for low-speed lift enhancement as well as speed brake control. Aircraft directional control was provided via a standard vertical tail-mounted rudder.

The No. 1 X-4 aircraft (S/N 46-676) first flew on Wednesday, 15 December 1948 at Muroc Air Force Base, California. Northrop test pilot Charles Tucker was at the controls. The X-4’s first mission revealed that the aircraft was slightly unstable in pitch. Moving the center-of-gravity forward by 3-inches corrected this problem on subsequent X-4 flights.

The No. 2 X-4 aircraft (S/N 46-677) took to the skies over Muroc Air Force Base for the first time on Tuesday, 07 June 1949 with Northrop’s Charles Tucker once again doing the honors. The second X-4 prototype’s air worthiness characteristics and handling qualities were found to be entirely satisfactory.

This vehicle was in fact superior to the No. 1 aircraft in several respects. Not the least of which was a better flight instrumentation suite.

A total of 17 pilots flew the X-4. Northrop’s Charles Tucker piloted all 30 of the contractor flights including 10 in the No. 1 ship and 20 in the No. 2 X-4. The remaining 82 flights were all flown in the No. 2 ship by USAF and NACA pilots including such luminaries as Stanley Butchart (NACA), Scott Crossfield (NACA), Pete Everest (USAF), Jack McKay (NACA), Joe Walker (NACA) and Chuck Yeager (USAF).

The X-4 achieved a maximum altitude of 42,300 on Tuesday, 29 May 1951 and a maximum speed of Mach 0.94 on Monday, 22 September 1952. NACA pilot Scott Crossfield, who piloted the most X-4 flights (31), was at the controls in both instances.

The X-4 handled well below Mach 0.87. However, the aircraft exhibited an annoying porpoising in pitch at higher transonic speeds. Nose-down pitch changes also produced a Mach-tuck effect that worsened with increasing Mach number. The X-4 also had a nasty tendency to pitch-up as it approached sonic speed. These issues were all related in one way or another to the type’s unique tailless, swept wing configuration.

The X-4 flight test program officially ended in September of 1953. Of the 112 total flight tests conducted over the program’s 58-month duration, 102 were flown by the No. 2 ship. While the X-4 never flew supersonically, the type’s transonic flight research program revealed that the hoped-for advantages of a tailless aircraft in supersonic flight were specious.

Happily, both X-4 aircraft survived the flight test program intact. X-4 No. 1 (S/N 46-676) is currently on display at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, CO. The No. 2 ship can be seen at the National Museum of the United States Air Force located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, OH.

Forty years ago today, the United States launched the Mariner 9 spacecraft on a mission to Mars. Among other achievements, Mariner 9 would become the first terrestrial spacecraft to orbit another planet other than Earth.

The Mariner Program was a NASA project whose goal was to investigate the planets Mars, Venus and Mercury from space. A total of ten (10) Mariner spacecraft were launched between 1962 and 1973. Seven (7) of these pioneering missions were considered successful. The first interplanetary flyby, the first orbiting of another planet and the first gravity assist maneuver were all accomplished by Mariner spacecraft.

Each Mariner was built around a central bus or housing that was either hexagonal or octagonal in shape. All spacecraft guidance, navigation, propulsion, communication, power and instrumentation systems were contained within or attached to this central bus. Mariner spacecraft were typically configured with a set of four (4) solar panels for power. However, Mariner’s 1, 2 and 10 used just two (2). Cameras were carried by all Mariner space probes with the exception of Mission’s 1, 2 and 5.

Mariner 9 carried a scientific instrumentation package that consisted principally of an imaging system, ultraviolet spectrometer, infrared spectrometer and infrared radiometer. Fully deployed, each pair of solar panels measured 22.6-feet across. These panels provided 800 watts of power at Earth and 500 watts at Mars. Power was stored in a 20-amp-hour nickel-cadmium battery.

Mariner 9 lift-off mass was 2,196 lbs. Propellant useage during the flyout to Mars resulted in a spacecraft mass of 1,232 lbs in Martian orbit. Scientific instrumentation accounted for 139-lbs of the on-rbit mass. Spacecraft propulsion for mid-course corrections and orbital insertion was provided by a 300-lb thrust liquid rocket motor burning monomethyl hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide. Mariner 9’s 3.28-foot diameter antenna telemetered data back to Earth at rates of 1, 2, 4, 8 or 16 kilobits/second using dual S-band 10 watt and 20 watt transmitters.

Mariner 9 was launched from Cape Canaveral’s LC-36B at 22:23:00 UTC on Sunday, 30 May 1971. An Atlas-Centaur SLV-3C launch vehicle provided the propulsive energy required to climb out of the Earth’s gravity well and send the probe on its way to Mars. It would take Mariner 9 roughly 167 Earth days to travel a distance of 214.85 million nautical miles to the Red Planet.

Mariner 9 entered Mars orbit at 00:18:00 UTC on Sunday, 14 November 1971. This marked the first time that a terrestrial spacecraft had achieved orbit about another planet in our Solar System other than Earth. Initial orbital parameters included an apoapsis of 9,672-nm and a periapsis of 755-nm at an inclination of 64.3 degrees. Interestingly, Mariner 9 arrived ahead of the Soviet Mars 2 space probe despite the latter’s eleven (11) day head start.

A planet-wide dust storm greeted Mariner 9 upon its arrival in Mars orbit. Hence, imaging of the planetary surface did not begin in earnest until late November. However, it was not until mid-January 1972 that the storm had subsided to the point that high quality images could be obtained from orbit.

Mariner 9 ultimately took 7,329 images which covered 100% of the Martian surface. The photos revealed a fascinating planetary topology that featured river beds, craters, extinct volcanoes, mountains and canyons. Mariner 9 discovered Olympus Mons, the largest known extinct volcano in the Solar System. Valles Marineris, a system of Martian canyons measuring 2,170-nm in length, was named after Mariner 9 in tribute to the probe’s significant space exploration accomplishments. Photographed as well were the diminutive Martian moons of Phobos and Deimos.

Upon depletion of its attitude control system propellant supply, Mariner 9’s mission was officially terminated when the spacecraft’s systems were turned-off on Friday, 27 October 1972. Total time spent investigating the Martian environment from orbit was 349-days. Though long silent, the craft remains in orbit around the Red Planet. It is expected to continue to do so through approximately the year 2022.

Forty-seven years ago this month, the No. 1 USAF/North American XB-70A Valkyrie aircraft was officially unveiled to the aviation public in a rollout ceremony conducted at USAF Plant 42 in Palmdale, California. The Great White Bird’s public debut occurred on Thursday, 11 May 1964.

The XB-70A Valkyrie was designed as an intercontinental bomber. Its original mission was to penetrate Soviet airspace and drop nuclear ordinance at Mach 3 and 70,000 feet. However, that mission was cancelled before the type ever flew. It was ultimately relegated to the status of an experimental flight research vehicle.

The XB-70A graced the skies of America between September 1964 and February 1969. It is to this day the largest triple-sonic aircraft ever flown. The aircraft measured 189 feet in length and had wing span of 105 feet. Gross weight topped out at around 540,000 lbs. Over half of that weight (290,000 lbs) was JP-6 jet fuel.

The Valkyrie was powered by six (6) General Electric YJ93 all-afterburning turbojets. These engines were designed to operate in continuous afterburner at Mach 3.2 and 95,000 feet. Total sea level thrust of the “6-Pack” was in excess of 185,000 lbs. The YJ93 was a contemporary of the Pratt and Whitney J58 turboramjet which powered the fabled USAF/Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird.

Only a pair of XB-70A airframes were built and flown; Air Vehicle No. 1 (S/N 62-0001) and Air Vehicle No. 2 (S/N 62-207). Together, these aircraft flew 129 flight tests totaling 252.6 flight hours. Ship No. 1 flew two-thirds of the XB-70A flight tests. The highest Mach number achieved during the XB-70A flight test program was Mach 3.08. This feat was accomplished by Ship No. 2 on Tuesday, 12 April 1966.

XB-70A Ship No. 2 also achieved the highest altitude of the XB-70A Program. Specifically, this aircraft attained a cruise altitude of 74,000 feet on Saturday, 19 March 1966. This mission included 32 minutes of continuous Mach 3 flight.

Eight (8) men flew the XB-70A. This line-up included Alvin S. White and Van H. Shepard of North American, Col Joseph E. Cotton, Lt Col Fitzhugh L. Fulton, Lt Col Emil (Ted) Sturnthal and Maj Carl S. Cross of the United States Air Force, and Joseph A. Walker and Donald L. Mallick of NASA.

The Valkyrie pioneered the use of numerous technologies including exploitation of the NACA Compression Lift Principle, development of honeycomb sandwich structural materials, and use of its fuel as a heat sink. The XB-70A was also used as a testbed for sonic boom research and a myriad of other aerodynamic and aerothermodynamic experiments. The Valkyrie also provided significant support to the ill-fated American Supersonic Transport (SST) effort.

XB-70A Ship No. 2 was lost in a collision with a NASA F-104N Starfighter near Edwards Air Force Base on Wedneday, 08 June 1966. This mishap took the lives of Maj Carl S. Cross and Joseph A. Walker on what is still referred to as the “Blackest Day at Edwards”. Ship No. 1 survived the XB-70 flight test program and is displayed today at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Forty-nine years ago this month, Mercury Astronaut M. Scott Carpenter orbited the Earth three times aboard his Aurora 7 Mercury spacecraft. In doing so, Carpenter became the second American to reach Earth orbit.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. A total of six (6) flights took place between May of 1961 and May of 1963. The first two (2) flights were suborbital missions while the remainder achieved low Earth orbits. In February of 1962, John H. Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth during the Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) mission.

Deke Slayton was to fly the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) mission. However, before that happened, the dreaded flight surgeon cabal grounded Slayton for what they claimed was a heart murmur. Despite Slayton’s utter incredulity and vehement protests, the decision held. Project Mercury officials maintained that the space program could ill afford the negative political fallout occasioned by the death of an astronaut on-orbit.

With Slayton grounded indefinitely, NASA selected Malcom Scott Carpenter to pilot the Mercury-Atlas 7 mission. Carpenter was member of the Original Seven selected by NASA for the Mercury Program in 1959. He was well prepared for the flight since he had just trained as Glenn’s MA-6 backup. As was the practice at that time, Carpenter named his Mercury spacecraft. The appellation he gave his celestial chariot was Aurora 7.

The launch of MA-7 took place on Thursday, 24 May 1962 from LC-14 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Lift-off time was 12:45:16 UTC. Ascent performance of the stage-and-a-half Atlas D booster was nearly flawless as it inserted Aurora 7 into a 140-nm x 83-nm elliptical orbit. Having been cleared for at least 3 orbits, Carpenter quickly got down to the business of spaceflight.

Much of the activity on the first and second orbits involved Carpenter maneuvering his spacecraft, conducting scientific experiments and observing the Earth from space. Among other discoveries, he discerned that John Glenn’s mysterious “fireflies” were simply particles of ice and frost that had accumulated on the shadow side of the spacecraft. When the spacecraft structure was bumped or vibrated, these particles would disperse from the external surface of the spacecraft and float into space. Once in the strong sunlight, the particles seemed to glow or be luminescent.

A combination of the astronaut’s spacecraft maneuvering and an intermittently malfunctioning pitch horizon scanner left Carpenter with less than half of his maneuvering fuel left at the start of the third and final orbit. Carpenter compensated admirably by barely using his thrusters during Orbit 3. Indeed, nearing the time of retro-fire, Aurora 7 still had 40 percent of his fuel remaining in both the manual and automatic flight control systems.

As retro-fire approached, the intermittent pitch horizon scanner malfunction reappeared at a most inopportune moment. The automatic stabilization and control system suddenly would not hold Aurora 7 in the proper attitude for retro-fire; heatshield 34 degrees above the horizon at zero yaw angle. Carpenter switched to manual mode in an attempt to align the spacecraft properly for retro-fire.

When nominal time for retro-fire came, the retro-rockets did not automatically ignite. Carpenter had to do that manually. But he was 3 seconds late. Worst, Aurora 7 was still yawed 25 degree to the right. And to top it off, retro-thrust was 3 percent low. All of this meant that Aurora 7 would overshoot the nominal landing point by 215 nautical miles.

The trip down through the atmosphere was sporty in that Carpenter ran out of attitude control system fuel early during the descent. This meant that there was no means to propulsively damp the side-to-side oscillations that the Mercury spacecraft normally exhibited during reentry. These oscillations became dangerous when they exceeded about 10 degrees. That is, the spacecraft could tumble end-over-end if left unchecked.

Carpenter simultaneously eyed the altimeter and spacecraft angle-of-attack. As the latter built-up dangerously, his only recourse was to manually fire the drogue earlier than planned in attempt to arrest Aurora 7’s oscillatory motion. He did so at 25,000 feet. The spacecraft’s side-to-side oscillations were stopped. Carpenter then deployed his main parachute at 9,500 feet. Splashdown occurred at 17:41:21 UTC at a point 108 nautical miles northeast of Puerto Rico.

Since Aurora 7 was listing badly and help was about an hour away, Carpenter extricated himself from the spacecraft and deployed his life raft. While a radio beacon helped recovery forces locate him, there was no voice communication between the astronaut and his rescuers. Carpenter was on the water nearly 3 hours before being picked-up by rescue helicopters and delivered to the carrier USS Intrepid. Some six (6) hours later, Aurora 7 was brought onboard the USS John R. Pierce.

Mercury-Atlas 7 was Scott Carpenter’s only space mission. A combination of factors, including less than amicable relations with Mercury Mission Control management, led to this being the case. During the intervening years, many stories alluding to pilot error or inattention as the cause of Aurora 7’s landing overshoot have been circulated. Indeed, much like Gus Grissom’s experience with the loss of his Liberty Bell spacecraft, these stories and explanations have been around long enough that they are now accepted as the “truth”.

Criticism of another’s performance comes easily in this world. However, as Theodore Roosevelt pointed out, it really is “The Man in the Arena” that counts most. In Scott Carpenter’s case, we simply turn the reader’s attention to NASA’s own post-flight report entitled “The Results of the United States Second Manned Orbital Mission”. Among other things, the subject report concluded that the Aurora 7 pilot overcame a “mission critical malfunction” of the pitch horizon scanner and “achieved all mission objectives”. And may we say that in so doing, Scott Carpenter’s MA-7 experience provides yet another validation of the man-in-the-loop concept so critical to the success of manned space operations.

Sixty-one years ago this month, Viking No. 4 soared to a record altitude of 91.2 nautical miles following launch from the USS Norton Sound. Known as Project Reach, the flight was conducted by the United States Navy to demonstrate the feasibility of using ship-launched rockets to carry scientific payloads into space.

The Viking rocket was the first large-scale, liquid-fueled launch vehicle to be developed by the United States. It’s primary mission was to carry scientific instrumentation and research payloads to altitudes as high as 140-nm. As such, the Viking was the domestic follow-on to the V2’s captured from Germany and flown on scientific missions from White Sands Proving Ground (WSPG) in New Mexico.

The Glenn L. Martin developed and built the Viking rocket for the United States Navy. The contract for doing so was let in August of 1946. A total of 12 airframes were built for the Viking Program. The Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) flew 11 of these vehicles between May of 1949 and February of 1955.

There were actually two Viking airframe configurations. The first 7 vehicles measured 47.5 feet in length and had a diameter of 32 inches. Depending on payload and propellant load, gross weight varied between 9,650 and 11,440 lbs. Viking’s 8-12 measured 41.4 feet in length and had a diameter of 45 inches. The average gross weight was 14,796 lbs.

The Viking rocket motor was a product of Reaction Motors Incorporated. It had a sea level thrust rating of 20,000 lbs. As was the case for the V2 rocket powerplant, the Viking’s propellants included alcohol (fuel) and liquid oxygen (oxidizer). Maximum demonstrated rocket motor burn time was 79 seconds for the Viking 1-7 series and 103 seconds for Vikings 8-12. The latter was longer due to the type’s larger propellant capacity.

The Viking’s nominal launch site was White Sands Proving Ground (WSPG) in New Mexico. However, early in the program, the Navy showed great interest in launching the vehicle from a ship at sea. The Navy’s biggest selling point for a shipboard launch was that researchers could choose their launch site. While the service had launched a V-2 from the deck of the USS Midway in 1947, the vehicle went into the drink shortly after lift-off when its control system failed. They hoped to do much better with the Viking.

Project Reach was the official name given to the Navy’s effort to conduct a shipboard launch of a Viking rocket. The USS Norton Sound, a ship that would figure prominently in the history of missile and space testing, was selected as the launch platform. The launch point chosen was the intersection of the Earth’s geographic and geomagnetic equators located near Christmas Island in the Pacific Ocean. The primary payload was a cosmic ray experiment weighing 394 lbs.

Viking No. 4 lifted-off from the deck of the USS Norton Sound at 1608 hours local time on Thursday, 11 May 1950. The vehicle rose straight and true into the partly cloudy tropical sky. Following a 74-second burn and a 168-second coast, the vehicle achieved an apogee of 91.2 nautical miles; the highest a Viking rocket had flown up to that time. Viking No. 4 impacted the ocean within sight of the launch ship about 435 seconds (7.25 minutes) after lift-off. Impact was supersonic.

Viking No. 4 gave the cosmic ray experimenta package a good ride and the data harvest was plentiful. Shipboard launch operations were uneventful in the main and entirely successful. Indeed, the experimentalists, the NRL launch operations team, the USS Norton Sound crew and the United States Navy were pleased with the results of the flight of Viking No. 4. Project Reach was a resounding success.

The Viking Program resumed launches back at WSPG in November of 1950. On Monday, 24 May 1954, Viking 11 reached an altitude of 137 nautical miles. It would be the all-time highest Viking flight.

The rapid pace of space technology during the second half of the 20th century soon caused Viking to fade into history. However, multi-disciplined technology developed during the Viking Program would influence the design and function of numerous subsequent launch vehicles. Perhaps the most direct example being the Navy’s 3-stage Vanguard satellite launch vehicle.

Sixty-four years ago this month, a missile launched on a flight test out of White Sands Proving Ground strayed from the test range and impacted near Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. The non-fatal mishap was attributed to a breakdown in range safety protocol.

The V2 missile (Vengeance Weapon No. 2) was developed by Nazi Germany during World War II for the purpose of attacking Allied population centers. As such, it was the world’s first ballistic missile. History records that more than 3,100 V2’s were fired in anger, with London, England and Antwerp, Belgium being the prime targets. Approximately 7,200 people lost their lives in V2 attacks between September 1944 and March 1945.

The V2 as flown by the Third Reich measured 46 feet in length and had a maximum diameter of 5.4 feet. Launch weight was 28,000 lbs. The V2’s rocket motor produced a maximum thrust of about 60,000 lbs at sea level. Ethyl alcohol and liquid oxygen served as fuel and oxidizer, respectively. Approximately 19,000 pounds of propellants were consumed in 65 seconds of boost flight.

The V2’s payload was an explosive warhead weighing about 1,600 lbs. The fearsome missile’s kinematic performance was impressive for its time. Maximum velocity was around 5,200 ft/sec. After burnout, the rocket followed a ballistic flight path all the way to the target. Maximum altitude and range for wartime missions was on the order of 50 nm and 175 nm, respectively.

With the defeat of Nazi Germany, both the United States and the Soviet Union gained access to a large number of V2 missiles and many of the German rocket scientists who developed the weapon. The United States shipped 300 rail freight cars full of V2 missile components back home. Under Operation Paperclip, some 126 German engineering and scientific personnel were expatriated to the United States. Initially operating out of Fort Bliss, Texas and White Sands Proving Ground (WSPG), New Mexico, these men were destined to make major contributions to the American space program. Among their number was one Werhner von Braun.

Sixty-seven V2 missiles were launched from White Sands Proving Ground (WSPG) between 1946 and 1952. These flights gave the United States invaluable experience in all aspects of rocket assembly, handling, fueling, launching and tracking. Indeed, V2 rocket technology and lessons-learned were applied in the development of all subsequent American launch vehicles ranging from the Redstone to the Saturn V. WSPG V2’s were also used to conduct numerous high altitude and space research experiments. Many aerospace “firsts” were achieved along the way. The first biological space payloads, first photographs of earth from space and the first large two-stage rocket flights involved the former vengeance weapon.

Rocket system reliability was not particularly good in the 1940’s and 1950’s. For instance, only 68% of the WSPG V2 flights were considered successful. Range safety was in its infancy too. In particular, the comprehensive range safety protocol that governs flight operations at today’s test ranges did not yet exist. This state of affairs was largely due to the fact that much of the systems knowledge and operations lessons-learned required to establish such a protocol had yet to be acquired. An incident that occurred in May of 1947 serves to underscore the reliability and safety issues just noted.

The Hermes II missile (RTV-G-3/RV-A-3) was a derivative of the basic V2 vehicle. The payload was a forward-mounted, winged, ramjet engine testbed. The V2’s tail surfaces were enlarged to counter the destabilizing influence of the payload’s wing group. The idea was to get the payload up to a Mach number beyond 3 and separate it from the V2 booster. Following separation, the ramjet pack would be ignited and thrust established. The payload would then fly a programmed altitude-Mach number flight profile. While ambitious on several levels, the project was certainly emblematic of this era of aerospace history wherein all manner of ideas took to the skies.

On Thursday, 29 May 1947, Hermes II was fired from Launch Complex 33 at White Sands Proving Ground. It was approximately 1930 hours local time. It is noted that the ramjet pack was not active for this first flight. The Hermes test vehicle was supposed to pitch to the north and fly uprange. Instead, it pitched to the south and backrange toward El Paso, Texas. Post-flight analysis revealed that the new inertial guidance system employed by the Hermes missile had been wired backwards! This human error directly and adversely affected rocket system reliability.

The WSPG Range Safety Officer(RSO) had both the authority and responsibility to hit the destruct button once it was obvious that the Hermes II was errant. However, a project scientist physically restrained the RSO from doing so! Apparently, the scientist was of the (evidently strong) opinion that the test vehicle’s propellant load should not be wasted on such trivial grounds as the safety of the El Paso populace. Unimpeded now, the errant rocket continued its flight. Range safety protocol would have to be improved and understood by all participants prior to the next flight!

The Hermes II reached a maximum altitude of 35 nm on its unplanned trip to the south. During its 5 -minute flight, the vehicle overflew the city of El Paso and impacted near the Tepeyac Cemetary located 3.5 miles south of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. The quasi-Mach 1 impact formed a crater that measured 50 feet in width and 24 feet in depth. Enterprising local residents gathered what little airframe wreckage that survived impact and sold it to souvenir seekers!

United States Army authorities quickly arrived on scene to ascertain the extent of the damage caused by the errant missile’s unannounced and unwelcome arrival. Happily, no lives were lost. Profuse apologies were delivered to and graciously accepted by Mexican government officials. The United States paid for all damages and effected a complete clean-up and remediation of the impact site.

A member of the team of expatriated German scientists who conducted the Hermes II flight test later was quoted as saying: “We were the first German unit to not only infiltrate the United States, but to attack Mexico from US soil!” Not nearly so amused, the Army tightened-up range safety protocol at WSPG in the aftermath of the international incident. Interestingly, historical evidence points to the likelihood that the Hermes II vehicle never did carry an active ramjet payload on test flights out of WSPG.