Fifty-five years ago this month, the first zero-length launch of an USAF/North American F-100D Super Sabre took place at Edwards Air Force Base, California. North American Test Pilot Albert R. Blackburn was at the controls of the experimental rocket-propelled test aircraft.

Zero-Length Launch (ZLL) was a concept pioneered by the United States Air Force for quickly getting aircraft into the air without the need for a conventional runway take-off. The idea was to launch the aircraft via rocket power from a standing start. Shortly after launch, the aircraft was at flight speed and the dead rocket booster was jettisoned.

The ZLL concept was typical of attempts by USAF to gain tactical advantage over the Soviet Union in any way possible during the Cold War era. ZLL held the promise of getting nuclear-armed combat aircraft airborne in the event that airfield runways were rendered useless due to enemy attack.

The ZLL mission was envisioned as one-way trip. Once airborne, a pilot was expected to fly to the target, deliver his nuclear weapon and then fend for himself. Survival options included finding a friendly field to land at or eject over non-hostile territory. Either way, the pilot’s chances of things working out well were not good.

The first attempt to test the ZLL concept dates back to 1953 when USAF employed the straight-wing USAF/Republic F-84G Thunderjet in the ZELMAL Program. ZELMAL stood for Zero Length Launch/ Mat Landing. This last part involved the aircraft making a wheels-up landing on an inflatable rubber mat that measured 800 ft x 80 ft x 3 ft.

Piloted ZELMEL flight tests were conducted at Edwards Air Force Base in 1954. The results were not particularly encouraging. Understandably, the mat landing was a rough go. The landing mat was heavily damaged on the first test and the pilot sustained back injuries that required months of recovery time. Subsequent flight tests showed ZELMAL to be essentially unworkable as then conceived.

USAF reprised the ZLL concept in 1958 with the F-100D Super Sabre. Gone was the mat landing part of the operation. The aircraft would make a normal wheels down landing if it got airborne successfully. Launch motive power was provided by a single Rocketdyne XM-34 solid rocket booster that generated 132,000 lbs of thrust for 4 seconds. At burnout of the boost motor, the F-100D was 400 feet above ground level and traveling at 275 mph. The booster was then jettisoned and the aircraft continued to accelerate under turbojet power.

The first flight test of the F-100 ZLL aircraft (S/N 56-2904) took place on Wednesday, 26 March 1958. The aircraft was launched from the south end of Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The test aircraft carried a pylon-mounted 275-gallon fuel tank on the right wing and a simulated nuclear store on a pylon under the left wing. North American’s Albert “Al” R. Blackburn served as the test pilot.

The first F-100 ZLL flight was entirely successful. Blackburn reported an exceptionally smooth ride on the rocket and an uneventful transition to turbojet-powered flight. While the boost motor struck the belly of the aircraft during departure and caused some superficial damage, the separation was otherwise successful. After a brief flight, Blackburn safely landed his steed on the concrete.

The first flight success of the ZLL Super Sabre was followed several weeks later by loss of aircraft 56-2904. Although the launch phase was proper, the boost motor hung-up on its support bolts and could not be jettisoned following burnout. Blackburn’s attempts to shake the dead motor free from the aircraft proved futile. Since a successful landing was not possible, he had to eject.

A total of fourteen (14) more F-100D ZLL flights took place at Edwards through October of 1958. Although these flights proved ZLL to be a viable means for getting a combat aircraft airborne without the use of a conventional runway take-off, USAF ultimately judged the concept to be too impractical and logistically burdensome to field. This in spite of the fact that a total of 148 F-100D Super Sabre aircraft were eventually modified for the ZLL mission.

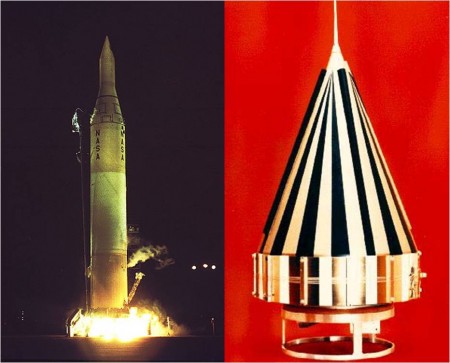

Forty-two years ago this month, a pair of SPRINT ABM interceptors fired from the Kwajalein Missile Range intercepted a reentry vehicle launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California. It was the first salvo launch of the legendary hypersonic interceptor.

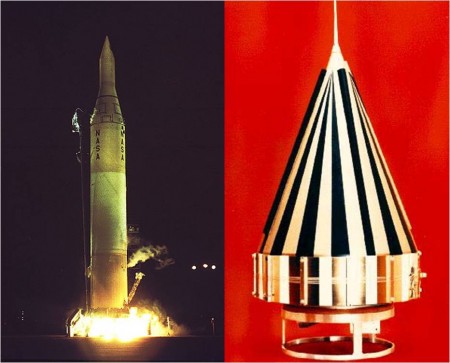

The Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) System was developed between the mid-960’s and mid-1970’s to protect United States ICBM sites. Safeguard consisted of an exoatmospheric missile (Spartan) and an endoatmospheric interceptor (SPRINT). In today’s missile defense parlance, we would refer to these vehicles as mid-course and terminal phase interceptors, respectively.

The 3-stage Spartan measured 55 feet in length, weighed 28,700 pounds at launch and had a range of 465 miles. Vehicle maximum velocity was in excess of 4,000 ft/sec. Spartan was armed with a 5-megaton nuclear warhead. Target destruction was effected via neutron flux.

The Solid Propellant Rocket INTerceptor (SPRINT) missile was a 2-stage vehicle. It measured 27 feet in length, weighed 7,500 pounds at launch and had a maximum range of 25 miles. SPRINT was configured with a nuclear warhead that had a yield on the order of several kilotons. Target destruction was also via radiation kill.

SPRINT’s performance was astounding by any measure. One second after first stage rocket motor ignition, the vehicle was already a mile away from the launch site. The Mach 5 stage separation event occurred a little over 1.2 seconds from first stage ignition.

The SPRINT upper stage saw a peak acceleration of 100 g’s and reached Mach 10 in about 6 seconds. Maximum mission duration was 15 seconds.

SPRINT’s rapid velocity build-up produced a correspondingly rapid rise in the vehicle’s surface temperature due to aerodynamic heating. The second stage glowed incandescently in daylight as its surface temperature exceeded that of an acetylene torch. The severe thermal state also resulted in the shock layer flow near the missile’s surface becoming a partially-ionized plasma.

SPRINT electromechanical and electronic equipment had to be ruggedized to handle the extreme shock, vibration, and acceleration environment of flight. In addition, the vehicle was hardened to withstand the severe pressure and electromagnetic pulses associated with a thermonuclear warhead detonation.

SPRINT flight testing started at White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) in November of 1965. Devoted to SPRINT subsystem testing, the WSMR flight test campaign ended in August 1970 and consisted of 42 shots.

Overall Safeguard system testing was conducted at the Kwajalein Missile Range (KMR) beginning in 1970 and extended through 1973. The KMR flight test program consisted of 34 flight tests. The first successful SPRINT intercept of a reentry vehicle took place in December 1970.

On Wednesday, 17 March 1971, SPRINT interceptors FLA-49 and FLA-50 were launched in salvo from Meck Island located on the eastern edge of the Kwajalein Atoll. The target for this mission was a Minuteman I reentry vehicle launched 4,800 miles to the east at Vandenberg Air Force Base. The target was successfully engaged and destroyed.

In October of 1974, a single Safeguard System unit became operational at Grand Forks Air Force Base, North Dakota. Interestingly, by February 1976, this lone deployed unit would be permanently deactivated. Thus ended the Safeguard ABM Program. A combination of high costs, questionable efficacy, lack of congressional support and international politics accounted for its very brief operational life.

Fifty-four years ago this week, NASA’s Pioneer 4 probe flew within 37,000 miles of the lunar surface. In doing so, the tiny spacecraft flew the first successful American lunar flyby mission.

The Pioneer Program involved a series of planetary space missions conducted by NASA between 1958 and 1978. The target of the early missions (1958-1960) was the Moon. The one exception was Pioneer 5 which investigated the interplanetary medium between Earth and Venus. Later Pioneer mission (1965-1978) were devoted to investigation of Jupiter and Saturn.

It was tough sledding in the early days of the Pioneer Program where the primary goal was to orbit the Moon. However, launch vehicle reliability was simply too poor and space trajectory control too crude to meet the lunar orbit goal in the lat 1950’s.

Indeed, none of the ten (10) Pioneer missions flown in the 1958-1960 period managed to achieve a lunar orbit of any kind. Interestingly, the United States would not orbit a spacecraft around the Moon until the Lunar Orbiter 1 mission in August of 1966.

While the lunar orbit goal proved too daunting for the early Pioneer Program, a lunar flyby mission appeared feasible using then-extant technology. The flyby mission simply required the spacecraft to sweep by the Moon (without impacting the surface) as the probe moved along an interplanetary trajectory towards the Sun. Ultimately, the spacecraft would find itself in solar orbit.

The Pioneer 4 spacecraft was a cone 20-inches in length and 9-inches in diameter. It weighed a mere 13.5 pounds. Probe spin-stabilization was effected by imparting an angular rate of 400 rpm about the vehicle’s longitudinal axis. Instrumentation was sparse; just a photoelectric sensor and a pair of radiation sensors.

On Tuesday, 03 March 1959, a Juno II launch vehicle carrying the Pioneer 4 spacecraft lifted-off from Cape Canaveral, Florida at 1711 UTC. The 4-stage Juno II was a modification of the Juno I launch vehicle that orbited America’s first satellite (Explorer 1) on Friday, 31 January 1958.

Pioneer 4 was successfully placed into an interplanetary trajectory that saw the probe pass within 37,000 miles of the lunar surface at 22:25 UTC on Wednesday, 04 March 1959. Considering that the Moon is about 238,000 miles from Earth, the flyby wasn’t all that close. However, at the dawn of the space age, it was indeed a significant accomplishment.

Pioneer 4 was powered by mercury batteries; that is, the spacecraft did not use solar cells. Sensor measurements were telemetered back to Earth at 960.05 MHz via a 0.1-Watt transmitter. Earth-based stations tracked the space probe out to a distance of roughly 407,000 miles from Earth.

At 01:00 UTC on Wednesday, 18 March 1959, Pioneer 4 reached the closest point in its eternal orbit about the Sun. Having done so, Pioneer 4 would forever hold the distinction of being the first American spacecraft to transit interplanetary space and reach heliocentric orbit.

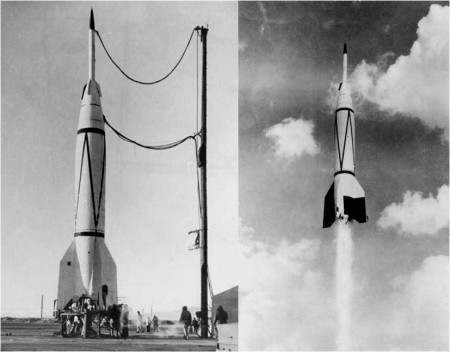

Sixty-four years ago this week, a United States two-stage liquid-fueled rocket reached a then-record altitude of 250 miles. Launch took place from Pad 33 at White Sands Proving Ground (WSPG), New Mexico.

The Bumper Program was a United States Army effort to reach flight altitudes and velocities never before achieved by a rocket vehicle. The name “Bumper” was derived from the fact that the lower stage would act to “bump” the upper stage to higher altitude and velocity than it (i.e., the upper stage) was able to achieve on its own.

The Bumper Program, which was actually part of the Army’s Project Hermes, officially began on Friday, 20 June 1947. The project team consisted of the General Electric Company, Douglas Aircraft Company and Cal Tech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. A total of eight (8) test flights took place between May 1948 and July 1950.

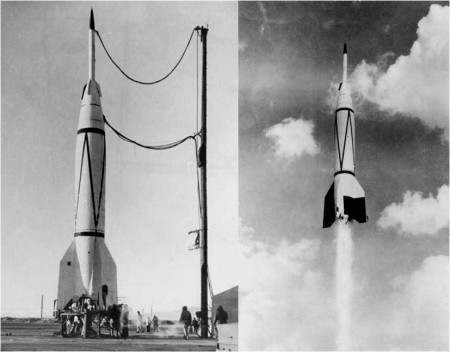

The Bumper two-stage configuration consisted of a V-2 booster and a WAC Corporal upper stage. The V-2’s had been captured from Germany following World War II while the WAC Corporal was a single stage American sounding rocket. The launch stack measured 62 feet in length and weighed around 28,000 pounds.

Propulsion-wise, the V-2 booster generated 60,000 pounds of thrust with a burn time of 70 seconds. The WAC Corporal rocket motor produced 1,500 pounds of thrust and had a burn time of 47 seconds.

The flight of Bumper-WAC No. 1 occurred on Thursday, 13 May 1948. This was an engineering test flight in which the WAC Corporal achieved a peak altitude of 79 miles. Unfortunately, the next three (3) flights were plagued by development problems of one kind or another and failed to achieve an altitude of even 10 miles.

Bumper-WAC No. 5 was fired from WSPG on Thursday, 24 February 1949. The V-2 burned-out at an altitude of 63 miles and a velocity of 3,850 feet per second. The WAC Corporal accelerated to a maximum velocity of 7,550 feet per second and then coasted to an apogee of 250 miles.

With generation of a very thin bow shock layer and high aerodynamic surface heating levels, the flight of Bumper-WAC No. 5 can be considered as the first time a man-made flight vehicle entered the realm of hypersonic flight. Notwithstanding that achievement, its maximum Mach number of 7.6 would be eclipsed in July of 1950 when Bumper-WAC No. 7 reached Mach 9.

Three (3) more Bumper-WAC missions would follow Bumper-WAC No.5. While Bumper-WAC No. 6 would fly from WSPG, the final two (2) missions were conducted from an isolated Florida launch site in July of 1950.

The hot, bug-infested Floridian launch location, springing-up amongst sand dunes and scrub palmetto, would one day become the seat of American spaceflight. It was known then as the Joint Long-Range Proving Ground. Today, we know it as Cape Canaveral.

The Bumper Program successfully demonstrated the efficacy of the multi-staging concept. Bumper also provided valuable flight experience in stage separation and high altitude rocket motor ignition systems. In short, Bumper played a vital role in helping America successfully develop its ICBM, satellite and manned spaceflight capabilities.

While its historical significance, and even its existence, has been lost to many here in the 21st Century, the Bumper Program played a major role in our quest for the Moon. As such, it will forever hold a hollowed place in the annals of United States aerospace history.

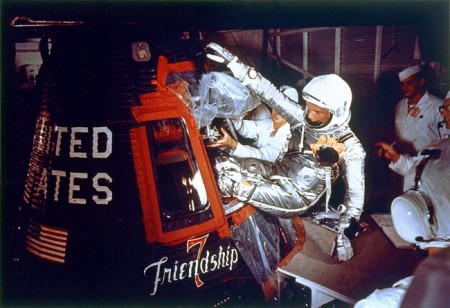

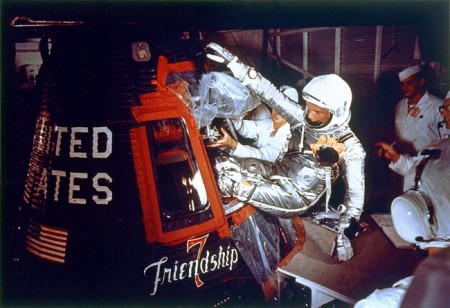

Fifty-one years ago this week, Project Mercury Astronaut John H. Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn’s spacecraft name and mission call sign was Friendship 7.

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 14 at 14:47:39 UTC on Tuesday, 20 February 1962. It was the first time that the Atlas LV-3B booster was used for a manned spaceflight.

Three-hundred and twenty seconds after lift-off, Friendship 7 achieved an elliptical orbit measuring 143 nm (apogee) by 86 nm (perigee). Orbital inclination and period were 32.5 degrees and 88.5 minutes, respectively.

The most compelling moments in the United States’ first manned orbital mission centered around a sensor indication that Glenn’s heat shield and landing bag had become loose at the beginning of his second orbit. If true, Glenn would be incinerated during entry.

Concern for Glenn’s welfare persisted for the remainder of the flight and a decision was made to retain his retro package following completion of the retro-fire sequence. It was hoped that the 3 straps holding the retro package would also hold the heat shield in place.

During Glenn’s return to the atmosphere, both the spent retro package and its restraining straps melted in the searing heat of re-entry. Glenn saw chunks of flaming debris passing by his spacecraft window. At one point he radioed, “That’s a real fireball outside”.

Happily, the spacecraft’s heat shield held during entry and the landing bag deployed nominally. There had never really been a problem. The sensor indication was found to be false.

Friendship 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at a point 432 nm east of Cape Canaveral at 19:43:02 UTC. John Glenn had orbited the Earth three (3) times during a mission which lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds. Within short order, spacecraft and astronaut were successfully recovered aboard the USS Noa.

John Glenn became a national hero in the aftermath of his 3-orbit mission aboard Friendship 7. It seemed that just about every newspaper page in the days following his flight carried some sort of story about his historic fete. Indeed, it is difficult for those not around back in 1962 to fully comprehend the immensity of Glenn’s flight in terms of what it meant to the United States and indeed the free world.

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. will turn 92 on 18 July 2013. His trusty steed, the Friendship 7 spacecraft, is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Five years ago this month, a United States Navy STANDARD Missile SM-3 Block IA intercepted and destroyed a failed NRO satellite at an altitude of 133 nautical miles. The relative velocity at intercept was in excess of 22,000 mph.

The United States Navy/Raytheon Missile Systems SM-3 (RIM-161) is the sea-based arm of the Missile Defense Agency’s Ballistic Missile Defense System (BMDS). The 3-stage missile carries a Kinetic Warhead (KW) that provides an exoatmospheric hit-to-kill capability.

In order to ensure a lethal hit, the SM-3 KW guides to a specific aimpoint on the target’s airframe. The ability to reliably do so has been impressively demonstrated in a series of intercept flight tests that began in 2002.

SM-3 rounds are launched from the MK-41 Vertical Launcher System (VLS) aboard United States Navy cruisers and destroyers. The at-sea basing concept provides for a high degree of operational flexibility in the ballistic missile intercept mission.

The Lockheed Martin-built USA-193 was launched on a classified mission from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB) at 2100 UTC on Thursday, 14 December 2006. Shortly after reaching orbit, contact with the 5,000-lb satellite was lost.

By January 2008, USA-193’s orbit had decayed to such an extent that its reentry appeared imminent. Such events raise concerns for the safety of those on Earth who reside within the debris impact footprint. However, there was an additional concern in the case of USA-193. The satellite still had about 1,000-lbs of hydrazine onboard.

Should the USA-193 hydrazine tank survive reentry, those living in the impact area would be exposed to a highly toxic cloud of the volatile substance. Officials concluded that the safest thing to do was to destroy the satellite before it reentered the atmosphere.

On Thursday, 21 February 2008, the USS Lake Erie was on station in the Pacific Ocean west of Hawaii. The US Navy cruiser fired a single SM-3 interceptor at 0326 UTC. Minutes later, the missile’s KW took out the satellite and dispersed its hydrazine load into space. Mission accomplished!

In the aftermath of the satellite take-down, Russia and others predictably accused the United States of using the USA-193 hydrazine issue as an excuse to demonstrate SM-3’s anti-satellite capability. While such capability was indeed demonstrated, noteworthy is the fact that all systems modified to execute the satellite intercept were subsequently returned to a ballistic missile defense posture.

Thirty-eight years ago this month, an USAF F-15A Eagle reached an altitude of 30 km (98,425 feet) 207.8 seconds from brake release. The pilot for the record-breaking mission was USAF Major Roger Smith.

Operation Streak Eagle was a mid-1970’s effort by the United States Air Force to set eight (8) separate time-to-climb records using the McDonnell-Douglas F-15 Air Superiority Fighter. These record-setting flights originated from Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Starting on Thursday, 16 January 1975, the 19th pre-production F-15 Eagle aircraft (S/N 72-0119) was used to establish the following time-to-climb records during Operation Streak Eagle:

3 km, 16 January 1975, 27.57 seconds, Major Roger Smith

6 km, 16 January 1975, 39.33 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

9 km, 16 January 1975, 48.86 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

12 km, 16 January 1975, 59.38 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

15 km, 16 January 1975, 77.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

20 km, 19 January 1975, 122.94 seconds, Major Roger Smith

25 km, 26 January 1975, 161.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

The eighth and final time-to-climb record attempt of Operation Streak Eagle took place on Saturday, 01 February 1975. The goal was to set a new time-to-climb record to 30 km. The pilot was required to wear a full pressure suit for this mission.

At a gross take-off weight of 31,908 pounds, the Streak Eagle aircraft had a thrust-to-weight ratio in excess of 1.4. The aircraft was restrained via a hold-down device as the two Pratt and Whitney F100 turbofan engines were spooled-up to full afterburner.

Following hold-down and brake release, the Streak Eagle quickly accelerated during a low level transition following take-off. At Mach 0.65, Smith pulled the aircraft into a 2.5-g Immelman. The Streak Eagle completed this maneuver 56 seconds from brake release at Mach 1.1 and 9.75 km. Rolling the aircraft upright, Smith continued to accelerate the Streak Eagle in a shallow climb.

At an elapsed time of 151 seconds and with the aircraft at Mach 2.2 and 11.3 km, Smith executed a 4-g pull to a 60-degree zoom climb. The Steak Eagle passed through 30 km at Mach 0.7 in an elapsed time of 207.8 seconds. The apex of the zoom trajectory was about 31.4 km. With a new record in hand, Smith uneventfully recovered the aircraft to Grand Forks AFB.

Operation Streak Eagle ended with the capturing of the 30 km time-to-climb record. In December 1980, the aircraft was retired to the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. It is currently held in storage at the Museum and no longer on public display.

Twenty-seven years ago today, the seven member crew of STS-51L were killed when the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch from LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. It was the first fatal in-flight accident in American spaceflight history.

In remarks made at a memorial service held for the Challenger Seven in Houston, Texas on Friday, 31 January 1986, President Ronald Wilson Reagan expressed the following sentiments:

“The future is not free: the story of all human progress is one of a struggle against all odds. We learned again that this America, which Abraham Lincoln called the last, best hope of man on Earth, was built on heroism and noble sacrifice. It was built by men and women like our seven star voyagers, who answered a call beyond duty, who gave more than was expected or required and who gave it little thought of worldly reward.”

We take this opportunity now to remember the heroic fallen:

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, Commander

Michael John Smith, Pilot

Ellison S. Onizuka, Mission Specialist One

Judith Arlene Resnik, Mission Specialist Two

Ronald Erwin McNair, Mission Specialist Three

S.Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist One

Gregory Bruce Jarvis, Payload Specialist Two

Speaking for his grieving countrymen, President Reagan closed his eulogy with these words:

“Dick, Mike, Judy, El, Ron, Greg and Christa – your families and your country mourn your passing. We bid you goodbye. We will never forget you. For those who knew you well and loved you, the pain will be deep and enduring. A nation, too, will long feel the loss of her seven sons and daughters, her seven good friends. We can find consolation only in faith, for we know in our hearts that you who flew so high and so proud now make your home beyond the stars, safe in God’s promise of eternal life.”

Tuesday, 28 January 1986. We Remember.

Four years ago this month, US Airways Flight 1549 successfully ditched in the Hudson River following loss of thrust in both turbofan engines. Incredibly, all 155 passengers and crew members survived.

US Airways Flight 1549 lifted-off from Runway 4 of New York’s LaGuardia Airport at 18:25:56 UTC on Thursday, 15 January 2009. The Airbus 320-214 (N106US) was making its 16,299th flight. Call sign for the day’s flight was Cactus 1549.

Captain Chesley B. Sullenberger III and First Officer Jeffrey B. Skiles were in the cockpit of Cactus 1549. Donna Dent, Doreen Welsh and Sheila Dail served as flight attendants. Together, these crew members were responsible for the lives of 150 airline passengers.

Following a normal take-off, Cactus 1549 collided with a massive flock of Canadian Geese climbing through 3,000 feet. Numerous bird strikes were experienced. Most critically, both CFM56-5B4/P turbofan engines suffered bird ingestion. As Captain Sullenberger succinctly described it later, the result was “sudden, complete, symmetrical” loss of thrust.

Quickly assessing their predicament, Captain Sullenberger instinctively knew that he could not get his aircraft back to a land-based runway. He was flying too low and slow to make such an attempt. He would have to ditch his 150,000-pound aircraft in the nearest waterway; the Hudson River.

The story of what ensued following loss of thrust is best told by Captain Sullenberger himself. The reader is therefore directed to chapters 13 and 14 of his post-mishap book entitled “Highest Duty”. The bottom line is that the aircraft was successfully ditched in the Hudson River roughly three and half minutes after loss of thrust.

Once the aircraft was on the water, the crew members evacuated all 150 passengers in less than 4 minutes. People either got into life rafts or stood on the aircraft’s wings. It was very cold. Air temperature was 21F with a windchill factor of 11F. The water temperature registered at 36F.

First responders from the New York Waterway quickly came to the aid of Cactus 1549. A total of fourteen vessels responded to the emergency with the first boat arriving within four minutes of the aircraft coming to a stop.

Many selfless acts of compassion and exemplary displays of valor were observed during Cactus 1549 rescue operations. This was true for those amongst the ranks of the rescuers and rescued alike.

Happily and to the great relief of the US Airways flight crew, there was no loss of life resulting from the emergency ditching of Cactus 1549. Now known as “The Miracle on the Hudson”, the events of that harrowing experience on a winter day in NYC will be forever remembered in the annals of aviation.

For their professional efforts in handling the Cactus 1549 in-flight emergency, Chesley Sullenberger, Jeff Skiles, Donna Dent, Doreen Welsh and Sheila Dail received the rarely-awarded Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators Master’s Medal on Thursday, 22 January 2009.

In part, the Master’s Medal citation read: “The reactions of all members of the crew, the split second decision making and the handling of this emergency and evacuation was ‘text book’ and an example to us all. To have safely executed this emergency ditching and evacuation, with the loss of no lives, is a heroic and unique aviation achievement.”

To which we say: Amen!

Fifty-five years ago this month, a XSM-64 Navaho G-26 flight test vehicle flew 1,075 miles in 40 minutes at a sustained speed of Mach 2.8. It was the 8th flight test of the ill-fated Navaho Program.

The post-World War II era saw the development of a myriad of missile weapons systems. Perhaps the most influential and enigmatic of these systems was the Navaho missile.

Navaho was intended as a supersonic, nuclear-capable, strategic weapon system. It consisted of two (2) stages. The first stage was rocket-powered while the second stage utilized ramjet propulsion. The aircraft-like second stage was configured with a high lift-to-drag airframe in order to achieve strategic reach.

While there were a number of antecedants dating back to 1946, the Navaho Program really began in 1950 as Weapon System 104A. The requirements included a range of 5,500 miles, a minimum cruise speed of Mach 3 and a minimum cruise altitude of 60,000 feet. The payload included an ordnance load of 7,000 pounds delivered within a CEP of 1,500 feet.

North American Aviation (NAA) proposed a 3-phase development plan for WS-104A. Phase 1 involved testing of the missile alone (the X-10) up to Mach 2. Phase 2 covered the testing of the two-stage launch vehicle (the G-26) up to Mach 2.75 and a range of 1,500 miles. Phase 3 would be the ultimate near-production vehicle (the G-38). Only Phase 1 and Phase 2 testing took place.

The Navaho missile-booster vehicle measured 84 feet in length and weighed about 135,000 pounds at lift-off. The launch weight for the booster was 75,000 pounds; most of which was due to the alcohol and LOX propellants. The missile empty weight was 24,000 pounds.

On Friday, 10 January 1958, Navaho G-26 No. 9 (54-3098) lifted-off from LC-9 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Climbing out under 240,000 pounds of thrust from its dual Rocketdyne XLR71-NA-1 rocket motors, missile-booster separation occurred at Mach 3.15 and 73,000 feet. Following air-start and take-over of twin Wright XRJ47-W-5 ramjets, generating a combined thrust of 16,000 pounds, the Navaho missile initiated a near triple-sonic cruise toward the Puerto Rico target area.

As the Navaho missile approached the environs of Puerto Rico, the vehicle was commanded to initiate a sweeping right-hand turn back towards the Cape. Unfortunately, the right intake experienced an unstart and a concommitant, asymmetric loss of thrust. Underpowered and without a restart capability, the vehicle was subsequently commanded to execute a dive into the Atlantic.

Flight No. 8, although only partially successful, flew longer and farther than any Navaho flight test vehicle. Only G-26 Flight No. 6 flew faster (Mach 3.5).

Although three (3) flights would follow G-26 Flight No. 8, all would suffer failure of one kind or another. In point of fact, the Navaho Program had been canceled on Saturday, 13 July 1957. The final six (6) Navaho flights were simply an attempt to extract the most from the remaining missile-booster rounds. Over 15,000 NAA employees lost their jobs the day Navaho died.

Navaho was cancelled primarily due to the ascendancy of the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). Very simply, an ICBM could deliver nuclear ordnance farther, faster and more accurately than a winged, unstealthy strategic missile. Navaho’s relatively numerous technical issues and programmatic delays simply served to drive the final nail into a long-prepared coffin.

While few today remember or even know of the Navaho Program, its technology has had a profound influence on all manner of aerospace vehicles up to the present day. Interestingly, the Space Shuttle launch vehicle concept bears a strong resemblance to the Navaho missile-booster combination. That is, a winged flight vehicle mounted asymmetrically on a longer boost vehicle.