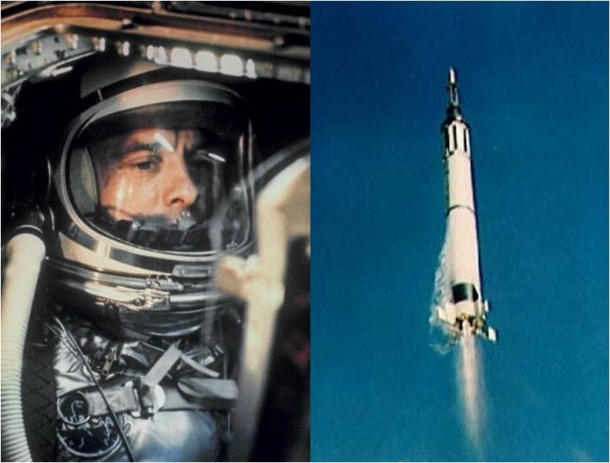

Fifty-one years ago today, NASA Astronaut Leroy Gordon Cooper was successfully launched into Earth orbit to begin a 22-orbit mission lasting 34 hours. Designated Mercury-Atlas No. 9 (MA-9), Cooper’s flight was the final orbital space mission of the fabled Mercury Program.

Cooper’s eventful space mission began with lift-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-14 at 13:04 hours UTC on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. Splashdown of his Faith 7 spacecraft occurred 70 miles southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, 16 May 1963. Mission total elapsed time was 34 hours 19-minutes 49-seconds.

While the first 19 orbits of the MA-9 mission were mostly unremarkable, the final three orbits severely tested Cooper’s mettle and piloting skills.

By the time that he manually initiated ripple-firing of the retro motors at the end of the 22nd orbit, Cooper was flying a dead spacecraft. The electrical system was not functioning, the environmental control system was saturated with carbon dioxide, and even the mission clock was inoperative. Temperatures in the spacecraft exceeded 130F.

Cooper had to align his spacecraft for retro-fire using the horizon as a reference, used a watch for timing, and manually operated the reaction control system to counter dangerous spacecraft oscillations during the retro burn.

Cooper also manually controlled Faith 7 during entry and initiated deployment of the drogue and main parachutes.

Incredibly, Cooper landed within 5 miles of the recovery ship USS Kearsarge. In so doing, he established the record for the most accurate landing in the Mercury Program. Gordon Cooper was the last American astronaut to orbit the Earth alone.

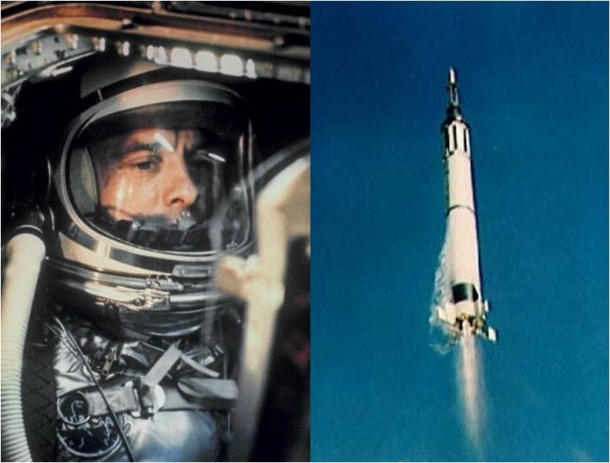

Fifty-three years ago today, United States Navy Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became the first American to be launched into space. Shepard named his Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7.

Officially designated as Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) by NASA, the mission was America’s first true attempt to put a man into space. MR-3 was a sub-orbital flight. This meant that the spacecraft would travel along an arcing parabolic flight path having a high point of about 115 nautical miles and a total range of roughly 300 nautical miles. Total flight time would be about 15 minutes.

The Mercury spacecraft was designed to accommodate a single crew member. With a length of 9.5 feet and a base diameter of 6.5 feet, the vehicle was less than commodious. The fit was so tight that it would not be inaccurate to say that the astronaut wore the vehicle. Suffice it to say that a claustrophobic would not enjoy a trip into space aboard the spacecraft.

Despite its diminutive size, the 2,500-pound Mercury spacecraft (or capsule as it came to be referred to) was a marvel of aerospace engineering. It had all the systems required of a space-faring craft. Key among these were flight attitude, electrical power, communications, environmental control, reaction control, retro-fire package, and recovery systems.

The Redstone booster was an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) modified for the manned mission. The Redstone’s uprated A-7 rocket engine generated 78,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. Alcohol and liquid oxygen served as propellants. The Mercury-Redstone combination stood 83 feet in length and weighed 66,000 pounds at lift-off.

On Friday, 05 May 1961, MR-3 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 5 at 14:34:13 UTC. Alan Shepard went to work quickly calling out various spacecraft parameters and mission events. The astronaut would experience a maximum acceleration of 6.5 g’s on the ride upstairs.

Nearing apogee, Shepard manually controlled Freedom 7 in all 3 axes. In doing so, he positioned the capsule in the required 34-degree nose-down attitude. Retro-fire occurred ontime and the retro package was jettisoned without incident. Shepard then pitched the spacecraft nose to 14 degrees above the horizon preparatory to reentry.

Reentry forces quickly built-up on the plunge back into the atmosphere with Shepard enduring a maximum deceleration of 11.6 g’s. He had trained for more than 12 g’s prior to flight. At 21,000 feet, a 6-foot droghue chute was deployed followed by the 63-foot main chute at 10,000 feet. Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 28 seconds after lift-off.

Following splashdown, Shepard egressed Freedom 7 and was retreived from the ocean’s surface by a recovery helicopter. Both he and Freedom 7 were safely onboard the carrier USS Lake Champlain within 11 minutes of landing. During his brief flight, Shepard had reached a maximum speed of 5,180 mph, flown as high as 116.5 nautical miles and traveled 302 nautical miles downrange.

The flight of Freedom 7 had much the same effect on the Nation as did Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927. However, in light of the Cold War fight against the world-wide spread of Soviet communism, Shepard’s flight arguably was more important. Indeed, Alan Shepard became the first of what Tom Wolfe called in his classic book The Right Stuff, the American single combat warrior.

For his heroic MR-3 efforts, Alan Shepard was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by an appreciative nation. In February 1971, Alan Shepard walked on the surface of the Moon as Commander of Apollo 14. He was the lone member of the original Mercury Seven astronauts to do so. Shepard was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Freedom in 1978.

Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia in July of 1998 at the age of 74. In tribute to this American space hero, naval aviator and US Naval Academy graduate, Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 spacecraft now resides in a place of honor at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

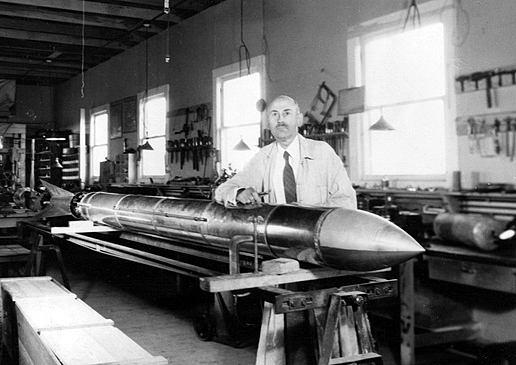

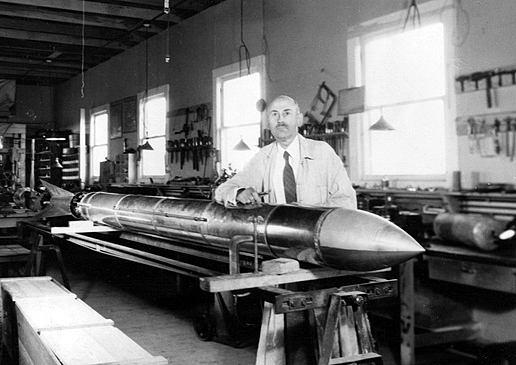

Seventy-nine years ago this month, pioneering rocket scientist Robert H. Goddard and staff fired a liquid-fueled rocket to a record altitude of 7,500 feet above ground level. The record-setting flight took place at Roswell, New Mexico.

Robert Hutchings Goddard was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on Thursday, 05 October 1882. He was enamored with flight, pyrotechnics, rockets and science fiction from an early age. By the time he was 17, Goddard knew that his life’s work would combine all of these interests.

Goddard was a sickly youth, but spent his well moments as a voracious reader of all manner of science-oriented literature. He graduated in 1904 from South High School in Worcester as the valedictorian of his class. He matriculated at Worcester Polytechnic and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in physics in 1908. A Master of Science degree and Ph.D. from Worcester’s Clark University followed in 1910 and 1911, respectively.

Goddard spent the next eight years of his life working on numerous propulsion and rocket-related projects. Then, in 1919, he published his now-famous scientific treatise entitled A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes. In that paper, the press glommed on to Goddard’s passing mention that a multi-staged rocket could conceivably fly all the way to the Moon.

Goddard was roundly ridiculed for his fanciful prognostications about Moon flight. The New York Times was especially derogatory in its estimation of Goddard’s ideas and accused him of junk science. A Times editorial even criticized Goddard for his ”misconception” that a rocket could produce thrust in the vacuum of space.

Even the U.S. government largely ignored Goddard. This scornful treatment to which Goddard was subject hurt him profoundly. So much so that he spent the remainder of his life alienated from the denizens of the press as well as the dolts of governmental employ.

Despite the blow to his professional reputation, Goddard resolutely pressed on with his rocket research. Indeed, after more that five years of intense development effort, Goddard and his staff launched the first liquid-fueled rocket on Tuesday, 16 March 1926 in Auburn, Massachusetts. The flight duration was short (2.5 seconds) and the peak altitude tiny (41 feet), but Goddard proved that liquid rocket propulsion was feasible.

Goddard’s liquid-fueled rocket testing would ultimately lead him from the countryside of New England to the desert of the Great South West. With financial support from Harry Guggenheim and the public backing of Charles Lindbergh, Goddard transfered his testing activities to Roswell, New Mexico in 1930. He would continue liquid-fueled rocket testing there until May 1941.

On Friday, 31 May 1935, experimental rocket flight A-8 took to the air from Goddard’s Roswell, New Mexico test site at 1430 UTC. Roughly 15 feet in length and weighing approximately 90 pounds at lift-off, the 9-inch diameter A-8 achieved a maximum altitude of 7,500 feet (1.23 nautical miles) above the desert floor. Only a flight in March of 1937 would go higher (9,000 feet).

Robert Goddard was ultimately credited with 214 U.S. patents for his rocket development work. Only 83 were awarded in his life time. His far-reaching inventions included rocket nozzle design, regenerativley cooled rocket engines, turbopumps, thrust vector controls, gyroscopic control systems and more.

Goddard died at the age of 62 from throat cancer in Baltimore, Maryland on Friday, 10 August 1945. Many years would pass before the full import of his accomplishments was comprehended. Then, the posthumously-bestowed recognition came in torrents. In 1959, Congress issued a special gold medal in Goddard’s honor. The Goddard Spaceflight Center was so named by NASA in 1959 as well. Many more such bestowals followed.

Perhaps the most meaningful of the recognitions ever accorded Robert Hutchings Goddard occurred 24 years after his passing. It was in connection with the first manned lunar landing in July of 1969. And it was poetic not only in terms of its substance and timing, but more particularly in light of the source from whence the recognition came.

A terse statement in the New York Times corrected a long-standing injustice. It read: “Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Issac Newton in the 17th century, and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vaccum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.”

Seventy-one years ago this month, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most intriguing and haunting stories in the annals of aviation. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

Forty-four years ago this month, the crew of Apollo 13 departed Earth and headed for the Fra Mauro highlands of the Moon. Less than six days later, they would be back on Earth following an epic life and death struggle to survive the effects of an explosion that rocked their spacecraft 200,000 miles from home.

Apollo 13 was slated as the 3rd lunar landing mission of the Apollo Program. The intended landing site was the mountainous Fra Mauro region near the lunar equator. The Apollo 13 crew consisted of Commander James A. Lovell, Jr., Lunar Module Pilot Fred W. Haise, Jr. and Command Module Pilot John L. (Jack) Swigert, Jr. Lovell was making his fourth spaceflight (second to the Moon) while Haise and Swigert were space rookies.

Apollo 13 lifted-off from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, 11 April 1970. The official launch time was 19:13:00 UTC (13:13 CST). During second stage burn, the center engine shutdown two minutes early as a result of excessive longitudinal structural vibrations. The outer four J-2 engines burned 34 seconds longer to compensate. Arriving safely in low Earth orbit, Lovell observed that every mission seemed to have at least one major glitch. Clearly, Apollo 13′s was now out of the way!

The Apollo 13 payload stack consisted of a Command Module (CM), Service Module (SM) and Lunar Module (LM). The entire ensemble had a lift-off mass of nearly 49 tons. In keeping with tradition, the Apollo 13 crew gave call signs to their Command Module and Lunar Modules. This helped flight controllers distinguish one vehicle from the other over the communications net during mission operations. The CM was named Odyssey and the LM was given the name of Aquarius.

The first two days of the outward journey to the Moon were uneventful. In fact, some at Mission Control in Houston, Texas seemed somewhat bored. The same could be said for the ever-astute press corps who predictably reported that Americans were now responding to the lunar landing missions with a collective yawn. The journalistic sages averred that the space program needed some pepping-up. Going to the Moon might have been impossible yesterday, but today its just run-of-the-mill stuff. Actually, it was all kind of easy. So wrote they of the fickle Fourth Estate.

It all started with a bang at 03:07:53 UTC on Tuesday, 14 April 1970 (21:07:53 CST, 13 April 1970) with Apollo 13 distanced 200,000 miles from Earth. “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” This terse statement from Jack Swigert informed Mission Control that something ominous had just occurred onboard Apollo 13. Jim Lovell reported that the problem was a “Main B Bus undervolt”. A potentially serious electrical system problem.

But what was the exact nature of the of problem and why did it occur? Nary a soul in the spacecraft nor in Mission Control could provide the answers. All anyone really knew at the moment was that two of three fuel cells formerly supplying electricity to the Command Module were now dead. Arguably more alarming, Oxygen Tank No. 2 was empty with Tank No. 1 losing oxygen at a high rate.

There was something else. The Apollo 13 reaction control system was firing in apparent response to some perturbing influence. But what was it? The answer came with all the subtlety of a sledge hammer blow. Jim Lovell reported that some kind of gas was venting from the spacecraft into space. That chilling observation suddenly explained why the No. 1 oxygen tank was losing pressure so rapidly.

Once Mission Control and the Apollo 13 astronauts fully comprehended the gravity of the situation, the entire team went to work to bring the spacecraft home. Odyssey was powered-down to conserve its battery power for reentry while Aquarius was powered-up and became a makeshift lifeboat. A major problem was that Aquarius had battery power and water sufficient for only 40 hours of flight. The trip home would take 90 hours.

Amazingly, engineering teams at Mission Control conceived and tested means to minimize electrical usage on Aquarius. However, the Apollo 13 crew would have to endure privation and hardships to survive. The cabin temperature in Aquarius got down to 38F and each man was permitted only six ounces of water per day. The walls of the spacecraft were covered with condensation. Sleep was almost impossible and fatigue became another unrelentless enemy to survival.

And then there was the build-up of carbon dioxide. The LM environmental system (EV) was designed to support two men. Now there were three. Between the CM and LM, there was an ample supply of lithium hydroxide canisters to scrub the gas from the cabin atmosphere for the trip home. However, the square CM canisters were incompatible with the circular openings on LM EV. The engineers on the ground invented a device to eliminate this compatibility using materials found onboard the spacecraft.

The Apollo 13 crew had to fire the LM descent motor several times in order to adjust their return trajectory. Use of the SM propulsion system to effect these firings was denied the crew due to concerns that the explosion could have damaged it. These rocket motor firings required precise inertial navigation. The star sightings required for celestial navigation were impossible to make owing to the huge cloud of debris surrounding the spacecraft. Means were devised to use the Sun as the primary navigational source.

As the nation and indeed the world looked on, the miracle of Apollo 13 slowly unfolded. Many a humble heart uttered a prayer for and in behalf of the trio of astronauts. Millions throughout the world followed the men’s journey home via newspaper, radio, television and other media.

As Apollo 13 approached the Earth, the overriding issue was whether the systems onboard Odyssey could be successfully brought back on line. The walls and instrument panels of the craft were drenched with condensation. Unquestionably, the electronics and wiring bundles behind those instrument panels were also soaking wet. Would they short-out once electrical energy flowed through them again? Would there be enough battery power for reentry?

Happily, the CM power-up sequence was successfully accomplished. Once again the resourceful engineers at Mission Control produced under extreme duress. They devised an intricate and never-attempted-in-flight power-up sequence for the CM. Too, the extra insulation added to the CM’s electrical system in the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire provided protection from condensation-induced electrical arcing.

Approximately four hours prior to reentry, the Apollo 13 crew jettisoned the SM. What they saw was shocking. The module was missing a complete external panel and most of the equipment inside was gone or significantly damaged. One hour prior to entry, Aquarius, their trusty space lifeboat, was also jettisoned. The only concern now was whether the Command Module base heatshield had survived the explosion intact.

On Friday, 17 April 1970, Odyssey hit entry interface (400,000 feet) at 36,000 feet per second. Other than a worrisome additional 33 seconds of plasma-induced communications blackout (4 minutes, 33 seconds total), the reentry was entirely nominal. Splashdown occurred at 18:07:41 UTC near American Samoa in the Pacific Ocean. The USS Iwo Jima quickly recovered spacecraft and crew.

The post-flight mishap investigation revealed that Oxygen Tank No. 2 exploded when the crew conducted a cryo-stir of its multi-phase contents. Unknown to all was the fact that a mismatch between the tank heater and thermostat had resulted in the Teflon insulation of the internal wiring being severely damaged during previous ground operations. This meant that the tank was now a bomb and would detonate its contents when used the next time. In this case, the next time was in flight. The warning signs were there, but went unheeded.

Apollo 13 never landed at Fra Mauro. And none of its crew would ever again fly in space. But in many ways, Apollo 13 was NASA’s finest hour. Overcoming myriad seemingly intractable obstacles in the aftermath of a completely unanticipated catastrophe, deep in trans-lunar space, will forever rank high among the legendary accomplishments of spaceflight. With essentially no margin for error and in the harsh glare of public scrutiny, NASA wrested victory from the tentacles of almost certain failure and brought three weary men safely back to their home planet.

Fifty-five years ago this month, NASA held a press conference in Washington, D.C. to introduce the seven men selected to be Project Mercury Astronauts. They would become known as the Mercury Seven or Original Seven.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. The overall objective of Project Mercury was to place a manned spacecraft in Earth orbit and bring both man and machine safely home. Project Mercury ran from 1959 to 1963.

The men who would ultimately become Mercury Astronauts were among a group of 508 military test pilots originally considered by NASA for the new role of astronaut. The group of 508 candidates was then successively pared to 110, then 69 and finally to 32. These 32 volunteers were then subjected to exhaustive medical and somewhat bizarre psychological testing.

A total of 18 men were still under consideration for the astronaut role at the conclusion of the demanding test period. Now came the hard part for NASA. Each of the 18 finalists was truly outstanding and would be a worthy finalist. But there were only 7 spots on the team.

On Thursday, 09 April 1959, NASA publicly introduced the Mercury Seven in a special press conference held for this purpose at the Dolley Madison House in Washington, D.C. The men introduced to the Nation that day will forever hold the distinction of being the first official group of American astronauts. In the order in which they flew, the Mercury Seven were:

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr., United States Navy. Shepard flew the first Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-3) on Friday, 05 May 1961. He was also the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Shepherd did so as Commander of Apollo 14 (AS-509) in February 1971. Alan Shepard died from leukemia on 21 July 1998 at the age of 74.

Vigil Ivan Grissom, United States Air Force. Grissom flew the second Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-4) on Friday, 21 July 1961. He was also Commander of the first Gemini mission (GT-3) in March 1965. Gus Grissom might very well have been the first man to walk on the Moon. But he died in the Apollo 1 Fire, along with Astronauts Edward H. White II and Roger Chaffee, on Friday, 27 January 1967. Gus Grissom was 40 at the time of his death.

John Herschel Glenn Jr., United States Marines. Glenn was the first American to orbit the Earth (MA-6) on Thursday, 22 February 1962. He was also the only Mercury Astronaut to fly a Space Shuttle mission. He did so as a member of the STS-95 crew in October of 1998. Glenn was 77 at the time and still holds the distinction of being the oldest person to fly in space. John Glenn is the only Mercury Seven astronaut still living and will be 93 in July 2014.

Malcolm Scott Carpenter, United States Navy. Carpenter became the second American to orbit the Earth (MA-7) on Thursday, 24 May 1962. This was his only mission in space. Carpenter subsequently turned his attention to under-sea exploration and was an aquanaut on the United States Navy SEALAB II project. Scott Carpenter passed away on 10 October 2013 at the age of 88.

Walter Marty Schirra Jr., United States Navy. Schirra became the third American to orbit the Earth (MA-8) on Wednesday, 03 October 1962. He later served as Commander of Gemini 6A (GT-6) in December 1965 and Apollo 7 (AS-205) in October 1968. Schirra was the only Mercury Astronaut to fly Mercury, Gemini and Apollo space missions. Wally Schirra suffered a fatal heart attack in May 2007 at the age of 84.

Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr., United States Air Force. Cooper became the fourth American to orbit the Earth (MA-9) on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. In doing so, he flew the last and longest Mercury mission (22 orbits, 34 hours). Cooper was also Commander of Gemini 5 (GT-5), the first long-duration Gemini mission, in August 1965. Gordo Cooper died from heart failure in October 2004 at the age of 77.

Donald Kent Slayton, United States Air Force. Slayton was the only Mercury Astronaut to not fly a Mercury mission when he was grounded for heart arrythemia in 1962. He subsequently served many years on Gemini and Apollo as head of astronaut selection. He finally got his chance for spaceflight in July 1975 as a crew member of the Apollo-Soyuz mission (ASTP). Deke Slayton succumbed to brain cancer in June of 1993 at the age of 69.

History records that the Mercury Seven was the only group of NASA astronauts that had a member that flew each of America’s manned spacecraft (i.e, Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Shuttle). Though just men and imperfect mortals, we salute each of them for their genuinely heroic deeds and unique contributions made to the advancement of American manned spaceflight.

Sixty-seven years ago today, the USAF/Convair XB-46 took to the skies on its maiden flight. Convair test pilot Ellis D. “Sam” Shannon was at the controls of the sleek, multi-jet prototype medium range bomber.

The XB-46 was a product of the flurry of aircraft design-build-and-fly activity that gripped the American aviation industry in the second half of the 1940’s. While most never saw the production line, all manner of new and innovative aircraft design concepts were built and flown by aircraft companies.

The XB-46 was a contemporary of and competitor with other jet-powered bomber concepts such as the North American XB-45 Tornado, North American XB-47 Stratojet, and Martin XB-48. With an unrefueled range of 2,500 nm and a service ceiling of 40,000 feet, the XB-46 was designed to carry a bomb load of 22,000 lbs.

The big bomber measured 105.75 feet in length and had a wingspan of 113 feet. Power was provided by a quartet of J35 turbojets which delivered 16,000 lbs of sea level thrust. The type’s gross take-off and empty weights were 95,000 lbs and 48,000 lbs, respectively.

The XB-46’s air crew consisted of a pilot and co-pilot who sat in tandem as well as a third crew member who was situated in the nose. This latter individual was a real jack-of-all-trades who served as the bombardier, navigator, and radio operator.

The one and only XB-46 aircraft (S/N 45-59582) departed on its first flight from Convair’s Lindbergh Field in San Diego on Wednesday, 02 April 1947. Pilot Sam Shannon headed north to Muroc Army Air Field where he safely landed an hour and a half later following an uneventful flight.

By the end of September 1947, the lone XB-46 aircraft had made 64 flights and spent 127 hours in the air. While the aircraft was found to have excellent stability and control characteristics and favorable handling qualities, the rapid pace of aeronautical progress quickly rendered it obsolete.

Although the XB-46 project was cancelled in August 1947, the airplane was transferred to Florida’s Palm Beach Air Force Base for additional flight testing. Researchers focused primarily on airframe structural and vibrational issues during the 44 hours of flight testing that took place from August 1948 to August 1949.

Although a worthy design concept that flew well, the XB-46 was eclipsed by a better airplane. In this case, the legendary USAF/Boeing B-47 Stratojet. But such was the fate of many post-WWII aircraft projects that vied for military production contracts during the fifth and sixth decades of the twentieth century.

The XB-46 exhibited a certain majesty in flight that was emblematic of the early jet age. Its development helped to improve the art of designing and flying large aircraft. As such, it would be nice to see it displayed in a prominent aviation museum. Regrettably, the single XB-46 prototype airframe was scrapped in the early 1950’s and no longer exists.

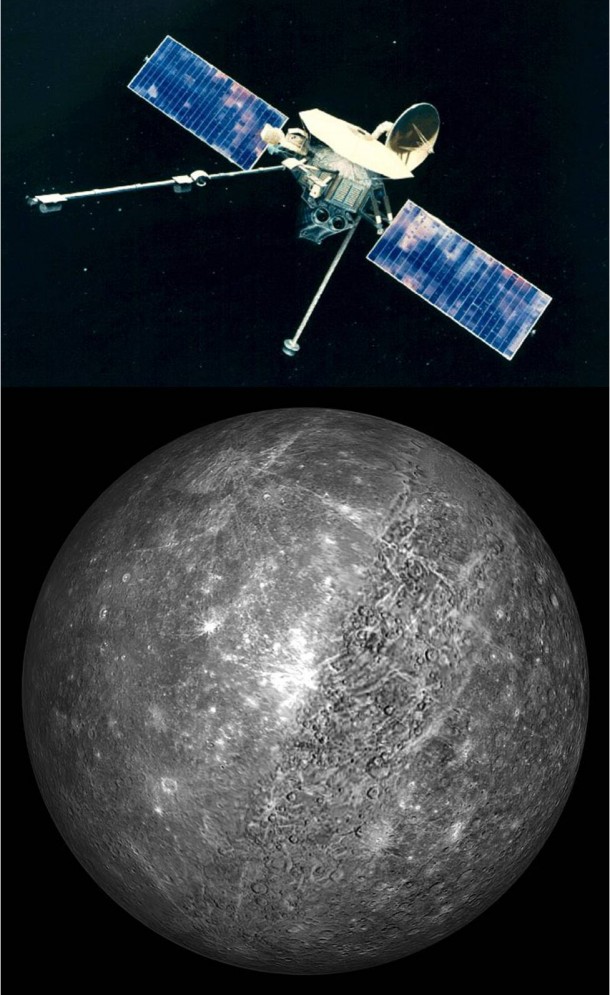

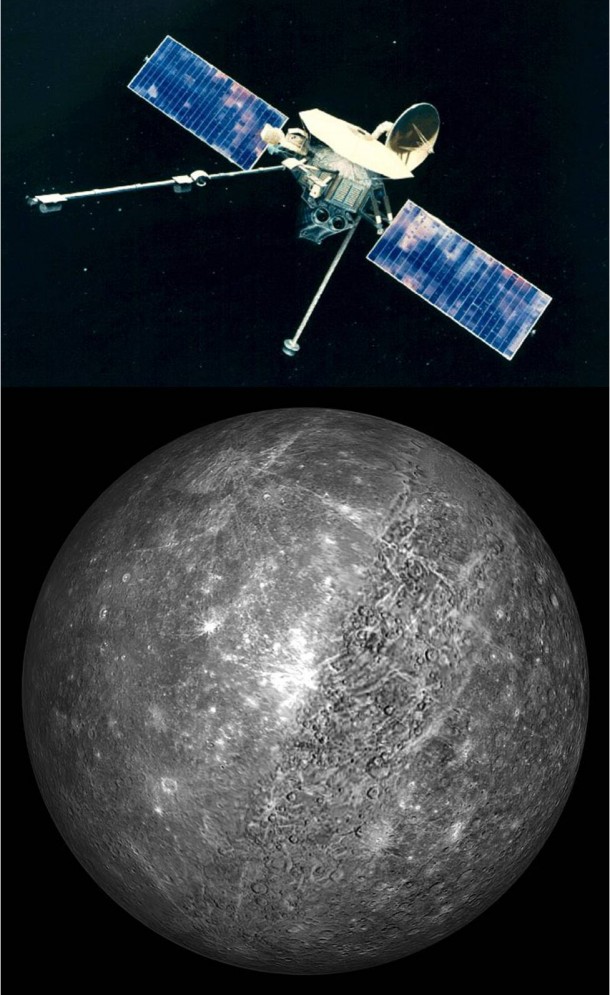

Forty-years ago this week, NASA’s Mariner 10 interplanetary probe conducted the first-ever flyby of the planet Mercury. Among other discoveries, Mariner 10 found that Mercury’s surface is heavily cratered much like the Moon.

Mercury is the smallest planet in the Solar System, having a diameter of slightly over 3,000 miles. Mercury is also the closest planet to the Sun, traveling in an elliptical orbit with an aphelion and perihelion of 43.3 and 28.6 million miles, respectively.

Its close proximity to the Sun explains why Mercury’s sunward surface temperature rise as high as 840 F. On the other hand, temperatures on the dark side of the planet can be as low as -275 F. This is the greatest known temperature differential for any planet in the Solar System.

Mercury is a fast mover by planetary standards. With an orbital velocity of about 112,000 mph, the tiny orb completes one orbit of the Sun in just 88 Earth-days.

NASA’s Mariner 10 interplanetary probe was the first spacecraft to conduct a flyby of the planet Mercury. This historic event occurred on Friday, 29 March 1974. The point of closest approach, only 437 miles above the Mercurian surface, took place at 20:47 UTC.

Mariner 10 found Mercury’s surface to be heavily pockmarked with impact craters. The probe also discovered that Mercury has a tenuous atmosphere composed mostly of helium, a very weak magnetic field, and a iron-rich core.

Mariner 10 went on to conduct flyby encounters with Mercury in September 1974 and March 1975. The third encounter brought the spacecraft within just 203 miles of the planet’s surface. More than 2,800 photographs of Mercury were taken by Mariner 10’s twin cameras during the historic trio of encounters.

As a footnote, Mariner 10 also conducted a flyby of the planet Venus in February 1974. The Mariner 10 mission was immensely successful and the last of the Mariner spacecraft series. Having long ago run out of attitude control system propellants and having its transmitter turned-off, Mariner 10 continues to silently orbit the Sun.

Sixty-seven years ago this week, the USAF/North American XB-45 Tornado bomber made its inaugural test flight at Muroc Army Air Field, California. The type would go on to become the United States first operational turbojet-powered bomber.

The XB-45 measured 74 feet in length, had a wingspan of 89.5 feet and a GTOW of 82,000 lbs. Power was provided by a quartet of Allison J35-A-7 turbojets producing a rather paltry 16,000 lbs of sea level thrust. With a maximum speed at sea level of roughly 500 mph, the service ceiling of the XB-45 was 37,600 feet.

A trio of XB-45 prototype aircraft were manufactured for the Air Force by North American. Serial numbers 45-59479, 45-59480, and 45-59481 were assigned to the three ships. Air crew consisted of two pilots who sat in tandem. The XB-45 flight test program included slightly more than 130 flights.

The first flight of the XB-45, Ship No. 1 (S/N 45-59479) took place on Monday, 17 March 1947 at Muroc Army Air Field, California. North American test pilot George W. Krebs was in the cockpit of the prototype bomber. The one-hour test hop was restricted to low speeds because the landing gear doors could not be fully closed.

Production versions of the Tornado included the B-45A, B-45C, and RB-45C. These aircraft were powered by General Electric J-47 turbojets and represented a great improvement relative to the XB-45 in terms of performance, operability, and reliability. Aircrew for the production Tornado variants included a pilot, co-pilot, bombardier-navigator, and tail gunner.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) used the RB-45C to fly clandestine recon missions over the Soviet Union between 1952 and 1954. Known as Operation Ju-jitsu, RB-45C aircrews gathered electronic and photographic intelligence information critical to the Free World’s defense posture. These high-risk RB-54C missions ultimately led to development of more capable recon aircraft; the Lockheed U-2 and SR-71.

The B-45 and RB-45 Tornado served in the Strategic Air Command (SAC) from 1950 through 1959. The B-45A holds the distinction of being USAF’s first operational jet-powered bomber as well as the first multi-jet bomber to be air-refueled. It was also the first jet bomber to carry and drop a nuclear weapon.

Fifty-eight years ago this month, the lone remaining USAF/Martin XB-51 light attack bomber prototype crashed during take-off from El Paso International Airport in Texas. The cause of the mishap was attributed to premature rotation of the aircraft leading to an unrecoverable stall.

A product of the post-WWII 1940’s, the Martin XB-51 was envisioned as a jet-powered replacement for the piston-driven Douglas A-26 Invader. The swept-wing XB-51 utilized a unique propulsion system which consisted of a trio of General Electric J47 turbojets. Demonstrated top speed was 560 knots at sea level.

The XB-51 was a good-sized airplane. With a length of 85 feet and a wing span of 53 feet, the XB-51 had a nominal take-off weight of around 56,000 lbs. The wings were swept 35 degrees aft and incorporated 6 degrees of anhedral. The latter feature to counter the large dihedral effect produced by the type’s tee-tail.

A pair of XB-51 aircraft were built by Martin for USAF. Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-0685) first took to the air in October of 1949 followed by the flight debut of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) in April of 1950. The air crew consisted of a pilot who sat underneath a large, clear canopy and a navigator housed within the fuselage.

While the XB-51 flew hundreds of hours in flight test and made many lasting contributions to the aviation field, the aircraft never went into production. This fate was primarily the result of having lost a head-to-head competitive fly-off against the English Electric Canberra B-57A light attack bomber in 1951.

The No. 1 XB-51 aircraft was lost on Sunday, 25 March 1956 during take-off from El Paso International Airport. The mishap aircraft accelerated more slowly than normal and with the end of the runway coming up quickly, the pilot rotated the aircraft in a attempt to get airborne. Unfortunately, the rotation was premature and the wing stalled. The aircraft exploded on impact and the crew of USAF Major James O. Rudolph and Staff-Sargent Wilbur R. Savage were killed.

The loss of the No. 1 XB-51 was preceded by the destruction of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) on Friday, 09 May 1952. That tragedy occurred during low-altitude aerobatic maneuvers at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The pilot, USAF Major Neil H. Lathrop, perished in the resulting post-impact explosion and inferno.

As a footnote, the XB-51 was never assigned an official nickname by the Air Force. However, it was unofficially referred to in some aviation circles as the Panther. Due to its prominently-long fuselage, the less majestic monicker of “Flying Cigar” was sometimes used as well.