Fifty-five years ago today, the USAF/NASA/North American X-15 became the first manned aircraft to exceed Mach 6. United States Air Force test pilot Major Robert M. White was at the controls of the legendary hypersonic flight research aircraft.

The North American X-15 was the first manned hypersonic aircraft. It was designed, engineered, constructed and first flown in the 1950’s. As originally conceived, the X-15 was designed to reach 4,000 mph (Mach 6) and 250,000 feet. Before its flight test career was over, the type would meet and exceed both performance goals.

North American built a trio of X-15 airframes; Ship No. 1 (S/N 56-6670), Ship No. 2 (56-6671) and Ship No. 3 (56-6672). The X-15 measured 50 feet in length, had a wing span of 22 feet and a GTOW of 33,000 lbs. Ship No. 2 would later be modified to the X-15A-2 enhanced performance configuration. The X-15A-2 had a length of 52.5 feet and a GTOW of around 56,000 lbs.

The Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine powered the X-15. The small, but mighty XLR-99 generated 57,000 pounds of sea level thrust at full-throttle. It weighed only 910 pounds. The XLR-99 used anhydrous ammonia and LOX as propellants. Burn time varied between 83 seconds for the stock X-15 and about 150 seconds for the X-15A-2.

The X-15 was carried to drop conditions (typically Mach 0.8 at 42,000 feet) by a B-52 mothership. A pair of aircraft were used for this purpose; a B-52A (S/N 52-003) and a B-52B (S/N 52-008). Once dropped from the mothership, the X-15 pilot lit the XLR-99 to accelerate the aircraft. The X-15A-2 also carried a pair of drop tanks which provided propellants for a longer burn time than was possible with the stock X-15 flight.

The X-15 employed both aerodynamic and reaction flight controls. The latter were required to maintain vehicle attitude in space-equivalent flight. The X-15 pilot wore a full-pressure suit in consequence of the aircraft’s extreme altitude capability. The typical X-15 drop-to-landing flight duration was on the order of 10 minutes. All X-15 landings were performed deadstick.

On Thursday, 09 November 1961, USAF Major Robert M. White would fly his 11th X-15 mission. The X-15 and White had already become respectively the first aircraft and pilot to hit Mach 4 and Mach 5. On this particular day, White would be at the controls of X-15 Ship No. 2. The planned maximum Mach number for the mission was Mach 6.

At 17:57:17 UTC of the aforementioned day, X-15 Ship No. 2 was launched from the B-52B mothership commanded by USAF Captain Jack Allavie. Bob White lit the XLR-99 and pulled into a steep climb. Mid-way through the climb, White pushed-over and ultimately leveled-off at 101,600 feet. XLR-99 burnout occurred 83 seconds after ignition. At this point, White was traveling at 4,093 mph or Mach 6.04.

On this record flight, the X-15 was exposed to the most severe aerodynamic heating environment it had experienced to date. Decelerating through Mach 2.7, the right window pane on the X-15’s canopy shattered due to thermal stress. The glass pane remained intact, but White could not see out of it. Fortunately, he could see out of the left pane and made a successful deadstick landing on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards AFB.

For his Mach 6+ flight, Bob White was a recipient of both the 1961 Collier Trophy and the Iven C. Kincheloe Award. The year before, White had received the Harmon Trophy for his X-15 flight test work. He would go on to fly the X-15 to a still-standing FAI altitude record of 314,750 feet in July of 1962. For this accomplishment, White was awarded USAF Astronaut Wings.

Bob White flew the X-15 a total of sixteen (16) times. He was one (1) of only twelve (12) men to fly the aircraft. White left X-15 Program and Edwards AFB in 1963. He went on to serve his country in numerous capacities as a member of the Air Force including flying 70 combat missions in Viet Nam. He returned to Edwards AFB as AFFTC Commander in August of 1970.

Major General Robert M. White retired from the United States Air Force in 1981. During his period of military service, he received numerous decorations and awards including the Air Force Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star with three oak leaf clusters, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters, Bronze Star Medal, and Air Medal with 16 oak leaf clusters.

Bob White was a true American hero. He was one of those heroes who neither sought nor received much notoreity for his accomplishments. He served his country and the aviation profession well. Bob White’s final flight occurred on Wednesday, 17 March 2010. He was 85 years of age.

Fifty years ago this month, NASA’s pioneering spaceflight program, Project Gemini, was brought to a successful conclusion with the 4-day flight of Gemini XII. Remarkably, the mission was the tenth Gemini flight in 20 months.

Boosted to Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle, Gemini XII Command Pilot James A. Lovell, Jr. and Pilot Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 20:46:33 UTC on Friday, 11 November 1966. The flight was Lovell’s second trip into space and Aldrin’s first.

Like almost every Gemini mission before it, Gemini XII was not a glitch-free spaceflight. For instance, when the spacecraft’s rendezvous radar began acting oddly, the crew had to resort to sextant and chart to complete the last 65 nautical miles of the rendezvous with their Agena Target Vehicle. But, overcoming this and other obstacles served to provide the experience and instill the confidence needed to meet the truly daunting challenge that lay ahead; landing on the Moon.

Unquestionably, Gemini XII’s single most important contribution to the United States manned space effort was validating the notion that a well-trained astronaut could indeed do useful work in an Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) environment. The exhausting and even dangerous EVA experiences of Gene Cernan on Gemini IX and Dick Gordon on Gemini XI brought into sharp focus the challenge of performing even seemingly simple work assignments outside the Gemini spacecraft.

Buzz Aldrin performed a trio of EVA’s on Gemini XII. Two of these involved standing in his seat with the hatch open. The third involved a tethered EVA or space walk. On the latter, Aldrin successfully moved about the exterior of the Gemini-Agena combination without exhausting himself. He also used a special-purpose torque wrench to perform a number of important work tasks. Central to Aldrin’s success was the use of foot restraints and auxiliary tethers to anchor his body while floating in a weightless state.

Where others had struggled and not been able to accomplish mission EVA goals, Buzz Aldrin came off conqueror. One of the chief reasons for his success was effective pre-flight training. A pivotal aspect of this training was to practice EVA tasks underwater as a unique means of simulating the effects of weightlessness. This approach was found to be so useful that it has been used ever since to train American EVA astronauts.

Lovell and Aldrin did many more things during their highly-compressed 4-day spaceflight in November of 1966. Multiple dockings with the Agena, Gemini spacecraft maneuvering, tethered stationkeeping exercises, fourteen scientific experiments, and photographing a total eclipse occupied their time aloft.

On Tuesday, 15 November 1966, on their 59th orbit, a tired, but triumphant Gemini XII crew returned to Earth. The associated reentry flight profile was automated; that is, totally controlled by computer. Yet another first and vital accomplishment for Project Gemini. Splashdown was in the West Atlantic at 19:21:04 UTC.

While Gemini would fly no more, both Lovell and Aldrin certainly would. In fact, both men would play prominent roles in several historic flights to the Moon. Jim Lovell flew on Apollo 8 in December 1968 and Apollo 13 in April 1970. And of course, Buzz Aldrin would walk on the Moon at Mare Tranquilitatis in July 1969 as the Lunar Module Pilot for Apollo 11.

Forty-two years ago today, the official rollout of the first USAF/Rockwell B-1A multi-role strategic bomber took place at the contractor’s USAF Plant 42 facility in Palmdale, California. The swing-wing, supersonic aircraft was intended to replace the venerable USAF/Boeing B-52 Stratofortress.

The USAF/Rockwell B-1A Lancer was the product of 1960’s-era Air Force studies calling for a supersonic-capable, low-level penetration bomber. North American Rockwell was awarded a contract to manufacture and test four (4) prototype airframes (S/N’s 74-0158, 74-0159, 74-0160 and 76-0174) in 1970. General Electric was selected as the powerplant provider.

The B-1A was designed for both Mach 2.3 flight at 50,000 feet and Mach 0.85 flight at sea level. The aircraft was able to satisfy these requirements by virtue of several design features. Formost among these was the aircraft’s ability to adjust its wing sweep in flight. Coupled with its sleek, aerodynamically-efficient fuselage, this gave the aircraft very low wave drag. Another key element were the type’s quartet of General Electric F-101 turbofan engines which generated a total of 120,000 lbs of afterburner thrust at sea level. Thrust performance was optimized through the use of variable-geometry air intakes.

The B-1A measured 150.2 feet in length and featured a wing span that could be varied in flight from 136.7 feet (15-deg sweep) to 78.2 feet (67.5-deg sweep). Gross take-off and empty weights were 395,000 lbs and 115,000 lbs, respectively. Unrefueld range was 5,300 nm. The aircraft was designed to carry 75,000 lbs of nuclear and/or conventional ordnance internally and up to 40,000 lbs externally. Operationally, the B-1A’s four-man crew would consist of aircraft commander, pilot, offensive systems officer and defensive systems officer.

The No. 1 B-1A (S/N 74-0158) was rolled out for the public on Saturday, 26 October 1974. About 10,000 people attended this event which took place at Rockwell’s facility on USAF Plant 42 property in Palmdale, California. The big, white, sleek aircraft was visually stunning and bore a majestic presence. The media covered the event in some detail.

The No. 1 B-1A took-off for the first time from USAF Plant 42 on Monday, 23 December 1974. The flight test aircrew included Charles Bock, Jr. (aircraft commander), Col. Emil (Ted) Sturmthal (pilot) and Richard Abrams (flight test engineer). The aircraft’s landing gear was not retracted and wing sweep was not varied during this initial flight test. These systems were operated on the type’s second flight test which occurred on Thursday, 23 January 1975.

Each of the B-1A prototypes served a distinct role in the aircraft’s flight test program. The No. 1 aircraft (74-0158) was the flying qualities evaluation testbed. It flew 79 times (405.3 hours) and was the first B-1A to hit Mach 1.5 (Oct 1975) as well as Mach 2 (Apr 1976). Aircraft No. 2 (S/N 74-0159) evaluated structural loading parameters, flew 60 times (282.5 hours), and achieved the highest Mach number of any B-1A aircraft (Mach 2.22 on Oct 1978). Aircraft No. 3 (S/N 74-0160) amassed 138 flights (829.4 hours) as an offensive and defensive systems testbed. Aircraft No. 4 (76-0174) had a similar role in that it tested essentially operational versions of the offensive and defensive systems. It flew 70 times (378 hours).

The B-1A program was cancelled by the Carter Administration in June of 1977. While it never attained operational status, the aircraft broke new ground in mutiple areas including aircraft design, aerodynamics, flight performance, and electronic warfare. Indeed, the multiple technological capabilities that it pioneered were ultimately exploited in the type’s direct heir; today’s USAF B-1B Lancer.

Fifty-one years ago this month, the USAF/North American XB-70A Valkyrie reached three times the speed of sound for the first time. The historic aviation achievement took place on the 18th anniversary of the breaking of the sound barrier by the USAF/Bell XS-1.

When it comes to legendary aircraft, aviation enthusiasts speak in almost reverent terms about the XB-70A Valkyrie. Indeed, few aircraft have evoked such utter awe or symbolized better the profound majesty of flight than the “The Great White Bird”. Though its flight history was brief, the XB-70A’s influence on aviation has proven to be of enduring worth.

The Valkyrie measured 185 feet in length, had a wingspan of 105 feet and an empty weight of 210,000 pounds. With a GTOW of 550,000 pounds, it was the heaviest supersonic-capable aircraft of all-time. The aircraft was powered by a six-pack of General Electric YJ93-GE-3 turbojets generating more than 172,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner.

To enhance lift-to-drag ratio and directional stability at high Mach number, the Valkyrie was configured with wing tips that could be deflected downward as much as 65 degrees. Each wing tip was the size of an USAF/Convair B-58A Hustler wing panel. To this day, the XB-70A deflectable wing tip is the largest control surface ever used on an aircraft.

The XB-70A was originally intended to be a supersonic strategic bomber. The aircraft’s mission was to penetrate Soviet airspace at Mach 3 and deliver nuclear ordnance from an altitude of 72,000 feet. However, the rapid ascendancy of Soviet surface-to-air missile capability would compromise the type’s military mission before it even flew.

As a consequence of the above, the Valkyrie ultimately became a high-speed flight research aircraft. Only two (2) copies were constructed and flown. Ship No. 1 (S/N 62-0001) made its maiden flight on Monday, 21 September 1964 while Ship No. 2 (62-0207) first took to the air on Saturday, 17 July 1965.

XB-70A Ship No. 1 became the first Valkyrie to hit Mach 3. It did so while flying at an altitude of 70,000 feet on Thursday, 14 October 1965. The flight crew consisted of North American Aviation test pilot Alvin S. White (aircraft commander) and USAF Colonel Joseph Cotton (co-pilot).

The XB-70A aircraft flew all of their flight research missions out of Edwards Air Force Base in California. Between September of 1964 and February of 1969, a total of 129 XB-70A research flights took places; 83 by Ship No. 1 and 46 by Ship No. 2. A total of nearly 253 flight hours was amassed by the aircraft.

The XB-70A Program made significant contributions to high-speed aircraft technology including aerodynamics, aerodynamic heating, flight controls, structures, materials, and air-breathing propulsion. Lessons-learned from its flight research have been applied to numerous aircraft developments including the B-1A, American SST, Concorde and the TU-144.

XB-70A Ship No. 1 survived the flight test program while Ship No. 2 did not. The latter was destroyed in a mid-air collision with a NASA F-104N on Wednesday, 08 June 1966. Today, XB-70A Ship No. 1 can be seen at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Forty-eight years ago this month, NASA successfully conducted the first manned Apollo Earth-orbital mission with the flight of Apollo 7. This mission was a critically-important milestone along the path to the first manned lunar landing in July 1969.

The launch of Apollo 7 took place from Launch Complex 34 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida at 15:02:45 UTC on Friday, 11 October 1968. The flight crew consisted of NASA astronauts Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham. Their primary goal was to thoroughly qualify the new Apollo Block II Command Module (CM) during 11 days in space.

Apollo 7 was not only the first flight of the Block II CM, but in fact the first manned mission in the Apollo Program. Apollo 7 also featured the first use of the Saturn IB launch vehicle in a manned mission. Apollo 7’s critical nature stemmed from the tragic Apollo 1 fire that took the lives of Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom, Edward H. White II, and Roger B. Chaffee on Friday, 27 January 1967.

The Apollo 1 fire was attributed to numerous deficiencies in the design, construction, and testing of its Block I CM. The Block II spacecraft flown on Apollo 7 was a major redesign of the Apollo Command Module and was in every sense superior to the Block I vehicle. However, it had taken 21 months to return to flight status and the Nation’s goal of a manned lunar landing within the decade of the 1960’s was in serious jeopardy.

The Apollo 7 crew orbited the Earth 163 times at an orbital altitude that varied between 125 and 160 nautical miles. In that time, they rigorously tested every aspect of their Block II CM. This testing included 8 firings of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) while in orbit. Apollo 7 splashdown occurred in the Atlantic Ocean near the Bermuda Islands at 11:11:48 UTC on Tuesday, 22 October 1968.

The Nation’s Lunar Landing Program overwhelmingly got the unqualified success that it desperately needed from the Apollo 7 mission. The Apollo Block II CM would provide yeoman service throughout the time of Apollo. The spacecraft would also go on to see service in the Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project programs.

While the technical performance of the Apollo 7 crew was unquestionably superb, their interaction with Mission Control at Johnson Spacecraft Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas was quite strained. The crew suffered from head colds through much of the mission and the food quality was poor. Coupled with Houston’s incessant attempts to cramp more tasks into each moment of the mission, Apollo 7 Commander Schirra took control of his ship and made the ultimate decisions as to what work would be performed onboard the spacecraft.

The flight of Apollo 7 would be Wally Schirra’s last mission in space as he had announced prior to flight. Schirra holds the distinction of being the only astronaut to have flown Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions.

Interestingly, Apollo 7 was not only Schirra’s last time in space, but it was Donn Eisele’s and Walt Cunningham’s first and last space mission as well. That there is a direct connection between this historical fact and the crew’s insubordinate behavior during Apollo 7 is obvious to the inquiring mind.

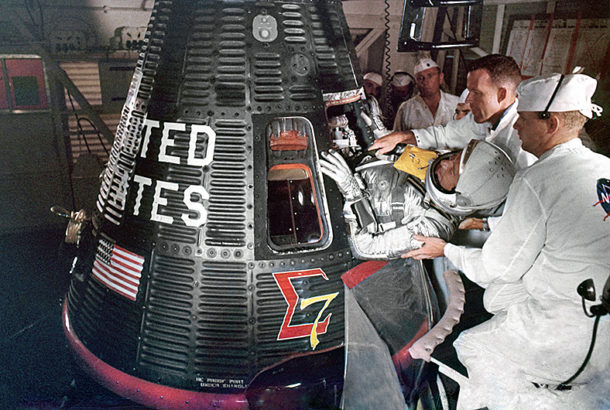

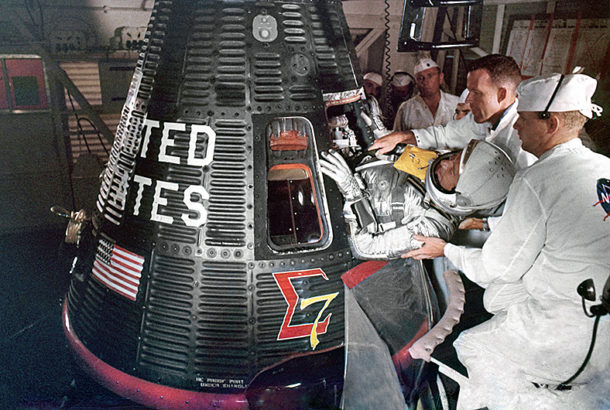

Fifty-four years ago this week, Mercury Astronaut Walter M. Schirra, Jr. orbited the Earth six (6) times in his Mercury spacecraft code-named Sigma 7. The near-perfect 9-hour spaceflight was the United States’ third manned orbital mission flown within a period of eight (8) months.

Project Mercury was United States’ first manned spaceflight program. This historic pioneering space effort helped lay the foundation for America’s quest for the Moon. A total of six (6) missions (2 sub-orbital and 4 orbital) was flown between May of 1961 and May of 1963.

The Mercury Spacecraft measured 11.5 feet in length and had a diameter of 6.2 feet. Orbital weight was roughly 3,000 pounds. With a cockpit volume of only 60 cubic feet, an astronaut’s corporeal fit inside the spacecraft was exceedingly tight. Vehicle entry and egress was a real shoe-horning process. It is not complete hyperbole to say that, once inside, an astronaut wore, more than rode in, the Mercury space vehicle.

Despite its dimunitive size, the Mercury Spacecraft was an able spacefaring ship. Indeed, it was configured with a complete suite of life support, navigation, attitude control, communications, deboost, recovery and thermal protection systems. Aided by a vast national mission support team, recovery force, and world-wide tracking system, the Mercury spaceflight effort was entirely successful in establishing America in space.

America’s first astronauts were known as the Mercury Seven. History records their names; Shepard, Grissom, Glenn, Carpenter, Schirra, Cooper and Slayton. In the tense 1960’s Space Race with the Soviet Union, these men were indeed America’s Single-Combat Warriors immortalized by writer Tom Wolfe in his classic, The Right Stuff.

Mercury-Atlas No. 8 (MA-8) was the fifth Mercury mission. Whereas the two (2) previous flights had been three (3) orbit missions, MA-8 was scheduled to orbit the Earth six (6) times. The focus would be on spacecraft operations instead of space science. The intent was to verify that the Mercury spacecraft could be cleared for an orbital mission duration of at least 24 hours on the very next flight

As was the custom for a Mercury astronaut, Schirra personally named his orbital steed. As such, Schirra chose the name Sigma 7. The term Sigma, the Greek mathematical symbol for summation, signified a summation or culmination of flight experience and engineering development that led to a mature Mercury Spacecraft system. The numeral 7 represented the Mercury Seven.

The MA-8 mission began with lift-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-14 at 12:15:12 UTC on Wednesday, 03 October 1962. The Atlas D launch vehicle placed Schirra into a 152.8-nm x 86.9-nm orbit. Once in orbit, Schirra quickly got down to business. This included tracking the Atlas booster, maneuvering the spacecraft, observing and photographing the Earth, and conducting various scientific experiments.

Schirra did a particularly good job at conserving the precious supply of Reaction Control System (RCS) fuel. One of the MA-8 objectives had been to do so. In fact, Schirra conserved fuel even more efficiently than planned. Other than an annoying and uncomfortable spacesuit heating problem that occurred several times, the entire MA-8 mission was what Schirra would ultimately call “textbook”.

MA-8 retro-fire occurred at 21:07:12 UTC. During the reentry, the automatic rate stabilization system damped spacecraft pitch and yaw oscillations. Drogue and main parachute deployment took place at 40,000 feet and 15,000 feet, respectively. Splashdown in the Pacific Ocean occurred 1,200 nm northwest of Hawaii at 21:28:22 UTC.

The success of MA-8 paved the way to Gordon Cooper’s historic 22-orbit, 34-hour MA-9 mission in May of 1963. The Gemini and Apollo Programs would soon follow. Wally Schirra would play a big part in both. He commanded the historic Gemini 6 orbital rendezvous mission in December of 1965. Schirra also went on to command the critical Apollo 7 mission in October of 1968.

Wally Schirra was the only member of the Mercury Seven to orbit the Earth in Mercury, Gemini and Apollo spacecraft. He left this earthly scene in May 2007 at the age of 84.

Sixty years ago today, the No. 1 USAF/Bell X-2 rocket-powered flight research aircraft reached a record speed of 2,094 mph with USAF Captain Milburn G. “Mel” Apt at the controls. However, victory quickly turned to tragedy when the aircraft departed controlled flight, crashed to destruction, and Apt perished.

Mel Apt’s historic achievement came about because of the Air Force’s desire to have the X-2 reach Mach 3 before turning it over to the National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics (NACA) for further flight research testing. Just 20 days prior to Apt’s flight in the X-2, USAF Captain Iven C. Kincheloe, Jr. had flown the aircraft to a record altitude of 126,200 feet.

On Thursday, 27 September 1956, Apt and the X-2 (Ship No. 1, S/N 46-674) dropped away from the USAF B-50 motherhip at 30,000 feet and 225 mph. Despite the fact that Mel Apt had never flown an X-aircraft, he executed the flight profile exactly as briefed. In addition, the X-2′s twin-chamber XLR-25 rocket motor burned propellant 12.5 seconds longer than planned. Both of these factors contributed to the aircraft attaining a speed in excess of 2,000 mph.

Apt and his aerial steed hit a peak Mach number of 3.2 at an altitude of 65,000 feet. Based on previous flight tests as well as flight simulator sessions, Apt knew that the X-2 had to slow to roughly Mach 2.4 before turning the aircraft back to Edwards. This was due to degraded directional stability, control reversal, and aerodynamic coupling issues that adversely affected the X-2 at higher Mach numbers.

However, Mel Apt was now faced with a difficult decision. If he waited for the X-2 to slow to Mach 2.4 before initiating a turn back to Edwards Air Force Base, he quite likely would not have enough energy and therefore range to reach Rogers Dry Lake. On the other hand, if he decided to initiate the turn back to Edwards at high Mach number, he risked having the X-2 depart controlled flight. Flying in a coffin corner of the X-2’s flight envelope, Apt opted for the latter.

As Apt increased the aircraft’s angle-of-attack, the X-2 departed controlled flight and subjected him to a brutal pounding. Aircraft lateral acceleration varied between +6 and -6 g’s. The battered pilot ultimately found himself in a subsonic, inverted spin at 40,000 feet. At this point, Apt effected pyrotechnic separation of the X-2′s forebody which contained the cockpit and a drogue parachute.

X-2 forebody separation was clean and the drogue parachute deployed properly. However, Apt still needed to bail out of the X-2′s forebody and deploy his personal parachute to complete the emergency egress process. However, it was not to be. Mel Apt ran out of time, altitude, and luck. The young pilot lost his life when the X-2 forebody from which he was trying to escape impacted the ground at a speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour.

Mel Apt’s flight to Mach 3.2 established a record that stood until the X-15 exceeded it in August 1960. However, the price for doing so was very high. The USAF lost a brave test pilot and the lone remaining X-2 on that fateful day in September 1956. The mishap also ended the USAF X-2 Program. NACA never did conduct flight research with the X-2.

However, for a few terrifying moments, Mel Apt was the fastest man alive.

Thirty-one years ago this month, the USAF/LTV ASM-135 anti-satellite missile successfully intercepted a target satellite orbiting 300 nautical miles above the Earth. The test was the first and only time that an aircraft-launched missile successfully engaged and destroyed an orbiting spacecraft.

The United States began testing anti-satellite missiles in the late 1950′s. These and subsequent vehicles used nuclear warheads to destroy orbiting satellites. A serious disadvantage of this approach was that a nuclear detonation intended to destroy an adversary satellite will likely damage nearby friendly satellites as well.

By the mid 1970′s, the favored anti-satellite (ASAT) approach had changed from nuclear detonation to kinetic kill. This latter approach required the interceptor to directly hit the target. The 15,000-mph closing velocity provided enough kinetic energy to totally destroy the target. Thus, no warhead was required.

The decision to proceed with development and deployment of an American kinetic kill weapon was made by President Jimmy Carter in 1978. Carter’s decision came in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s successful demonstration of an orbital anti-satellite system.

LTV Aerospace was awarded a contract in 1979 to develop the Air-Launched Miniature Vehicle (ALMV) for the USAF. The resulting anti-satellite missile (ASM) system was designated the ASM-135. The two-stage missile was to be air-launched by a USAF F-15A Eagle executing a zoom climb. In essence, the aircraft acted as the first stage of what was effectively a 3-stage vehicle.

The ASM-135 was 18-feet in length and 20-inches diameter. The 2,600-lb vehicle was launched from the centerline station of the host aircraft. The ASM consisted of a Boeing SRAM first stage and an LTV Altair 3 second stage. The vehicle’s payload was a 30-lb kinetic kill weapon known as the Miniature Homing Vehicle (MHV).

The ASM-135 was first tested in flight on Saturday, 21 January 1984. While successful, the missile did not carry a MHV. On Tuesday, 13 November 1984, a second ASM-135 test took place. Unfortunately, the missile failed when the MHV that it was carrying was aimed at a star that served as a virtual target. Engineers went to work to make the needed fixes.

In August of 1985, a decision was made by President Ronald Reagan to launch the next ASM-135 missile against an orbiting US satellite. The Solwind P78-1 satellite would serve as the target. Congress was subsequently notified by the Executive Branch regarding the intended mission.

The historic satellite takedown mission occurred on Friday, 13 September 1985. USAF F-15A (S/N 77-0084), stationed at Edwards Air Force Base, California and code-named Celestial Eagle, departed nearby Vandenberg Air Force Base carrying the ASM-135 test package. Major Wilbert D. Pearson was at the controls of the Celestial Eagle.

Flying over the Pacific Ocean at Mach 1.22, Pearson executed a 3.8-g pull to achieve a 65-degree inertial pitch angle in a zoom climb. As the aircraft passed through 38,000-feet at Mach 0.93, the ASM-135 was launched at a point 200 miles west of Vandenberg. Both stages fired properly and the MHV intercepted the Solwind P78-1 satellite within 6-inches of the aim point. The 2,000-lb satellite was completely obliterated.

In the aftermath of the stunningly successful takedown of the Solwind P78-1 satellite, USAF was primed to continue testing the ASM-135 and then introduce it into the inventory. Plans called for upwards of 112 ASM-135 rounds to be flown on F-15A aircraft stationed at McChord AFB in Washington state and Langley AFB in Virginia. However, such was not to be.

Even before the vehicle flew, the United States Congress acted to increasingly restrict the ASM-135 effort. A ban on using the ASM-135 against a space target was put into effect in December 1985. Although USAF actually conducted successful additional ASM-135 flight tests against celestial virtual targets in 1986, the death knell for the program had been sounded.

In the final analysis, a combination of US-Soviet treaty concerns, tepid USAF support and escalating costs killed the ASM-135 anti-satellite effort. The Reagan Administration formally cancelled the program in 1988.

While the ASM-135 effort was relatively short-lived, the technology that it spawned has propagated to similar applications. Indeed, today’s premier exoatmospheric hit-to-kill interceptor, the United States Navy SM-3 Block IA anti-ballistic missile, is a beneficiary of ASM-135 homing guidance, intercept trajectory and kinetic kill weapon technologies.

Sixty years ago this month, the USAF/North American F-107A aircraft flew for the first time. Interestingly, the Mach 2-capable fighter-bomber prototype went supersonic on its maiden flight.

The F-107A was designed, developed and tested by North American Aviation (NAA) in the mid-1950′s. With it, the contractor hoped to satisfy Tactical Air Command’s (TAC) need for a front line fighter-bomber. However, Republic Aircraft also had a candidate for the same role; the F-105 Thunder Chief.

The competition between Republic and North American for the TAC fighter-bomber production contract has a story of its own. Suffice it to say here that the competitive effort was (1) extremely close and (2) tinged with political intrigue. In the end, Republic Aircraft reaped the spoils of victory.

Although the F-107A came out on the short end of the stick in the TAC fighter-bomber competition, such did not imply an inferiority in fulfilling the intended role. Indeed, like the Northtrop YF-23′s loss to the General Dynamics YF-22 in the ATF competition of the early 1990′s, North American’s failure to get the nod with the F-107A is still a subject of passionate debate.

The F-107A measured 60.8 feet in length and had a wing span of 36.6 feet. Gross take-off weight was around 41,000 pounds. The aircraft was powered by a single Pratt and Whitney YJ75-P-11 turbojet that produced 15,500 pounds of thrust in military power and 23,500 pounds of thrust in full afterburner.

F-107A longitudinal control was provided by an all-flying horizontal tail. Similarly, an all-flying vertical tail was employed for directional control. Lateral control was provided by a unique 3-segment spoiler-deflector system mounted on each wing. The aircraft was also configured with inboard flaps and leading edge slats for lift augmentation at low speeds.

A unique and prominent feature of the F-107A was its dorsal-mounted air induction system known as the Variable-Area Inlet Duct (VAID). Internally, this unit incorporated a system of adjustable ramps to efficiently decelerate and compress freestream prior to entering the engine compressor face. Ramp deflection scheduling with Mach number was controlled automatically. Ramp boundary layer bleed air was vented from the top of the VAID.

The F-107A carried weapons externally. In addition to wing pylon-mounted stores, the aircraft was designed to carry a single “special weapon” from a semi-submerged recess located on the aircraft ventral centerline. The term “special weapon” means that it was a tactical nuclear bomb. The Sandia-developed store could also be used in combination with a special saddle fuel tank to extend aircraft range.

A total of three (3) F-107A aircraft were built and flown. USAF-assigned tail numbers include 55-5118, 55-5119 and 55-5120. On Monday, 10 September 1956, the No. 1 ship (55-5118) took-off from Edwards Air Force Base on its first flight. NAA Chief Test Pilot Robert Baker, Jr. was at the controls. The aircraft attained a maximum Mach number of 1.03 in a 43 minute flight test.

The F-107A could really scream. The type had a maximum climb rate of around 40,000 feet per minute in full afterburner. The max demonstrated Mach number attained by the F-107A was Mach 2.18. Program engineers estimated that by increasing the inlet area slightly, the F-107A was capable of reaching roughly Mach 2.4.

The trio of F-107A aircraft flew 272 flight tests totalling 176.5 hours. Included in this testing was successful separation of a special store prototype at Mach 2. Test pilots of note who flew the F-107A included XB-70A pilot Al White and X-15 pilots Scott Crossfield, Bob White, Jack McKay and Forrest Peterson.

Though it never became a production aircraft, the F-107A contributed in significant ways to aviation progress. Indeed, many future aircraft would greatly benefit from F-107A flight control and air induction technology including the A-5 Vigilante, XB-70A, A-12, SR-71, YF-12A and F-15.

The F-107A was the last of NAA’s fighter aircraft which includes such notables as the P-51 Mustang, the F-86 Sabre and the F-100 Super Sabre. While the F-107A has often been referred to in print as the Ultra Sabre, Ultimate Sabre, Super Super Sabre or such, it was never officially assigned a nickname. Alas, there was never an XF-107A or YF-107A designation either. North American Aviation’s TAC fighter-bomber candidate was simply known as the F-107A.

Today, the No. 1 F-107A (55-5118) is displayed at the Pima Air and Space Museum (PASM) in Tucson, Arizona. The No. 2 ship (55-5119) resides at the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. The No. 3 airplane (55-5120) no longer exists as it was relegated to the status of a fire fighting prop and ultimately destroyed in that role sometime in 1961 or 1962.

Sixty years ago today, the rocket-powered USAF/Bell X-2 aircraft established a new altitude record when the vehicle soared to 126,200 feet above sea level. This historic accomplishment took place on the penultimate mission of the type’s troubled 20-flight aeronautical research program.

The X-2 was the successor to Bell’s X-1A rocket-powered aircraft which had recorded maximum speed and altitude marks of 1,650 mph (Mach 2.44) and 90,440 feet, respectively. The X-2 was designed to fly beyond Mach 3 and above 100,000 feet. The X-2’s primary mission was to investigate aircraft flight control and aerodynamic heating in the triple-sonic flight regime.

The X-2 had a gross take-off weight of 24,910 lbs and was powered by a Curtis-Wright XLR-25 rocket motor which generated 15,000-lbs of thrust. Aircraft empty weight was 12,375 lbs. Like the majority of X-aircraft, the X-2 was air-launched from a mothership. In the X-2’s case, an USAF EB-50D served as the drop aircraft. The X-2 was released from the launch aircraft at 225 mph and 30,000 feet.

The day was Friday, 07 September 1956. The pilot for the X-2 maximum altitude mission was USAF Captain Iven Carl Kincheloe, Jr. Kicheloe was a Korean War veteran and highly accomplished test pilot. He wore a partial pressure suit for survival at extreme altitude.

While the dynamic pressure at the apex of his trajectory was only 19 psf, Kincheloe successfully piloted the X-2 with aerodynamic controls only. The X-2 was not configured with reaction controls. Mach number over the top of the trajectory was supersonic (approximately Mach 1.7).

Kicheloe’s maximum altitude flight in the X-2 (S/N 46-674) would remain the highest altitude achieved by a manned aircraft until August of 1960 when the fabled X-15 would fly just beyond 136,000 feet. However, for his achievement on this late summer day in 1956, the popular press would refer to Iven Kicheloe as the “First of the Space Men”.