Fifty-five years ago today, President John F. Kennedy called a special session of the United States Congress to bring before that august body a variety of issues which he referred to as “urgent national needs”.

The transcript of President Kennedy’s speech indicates that the ninth and last issue addressed by the President was simply entitled SPACE. The most stirring words of that portion of his speech may well be these:

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Although he did not live to see the fulfillment of that goal, the record shows that 8 years, 1 month, and 26 days later, the United States of America did indeed land a man (men) on the moon and returned him (them) safely to earth before the decade was out.

Thus, as a country, we can say now, even as we said then to our departed leader: Mission Accomplished, Mr. President.

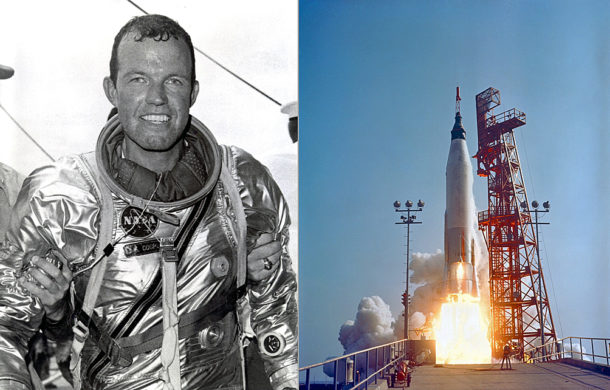

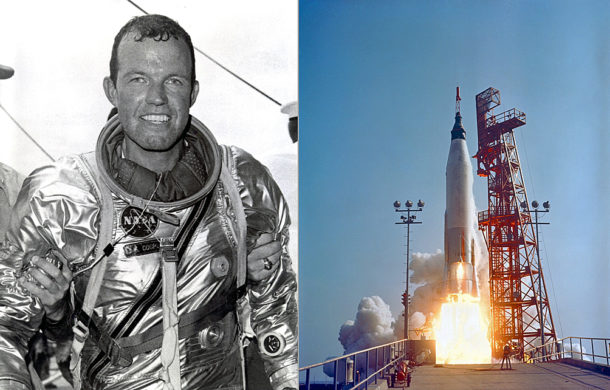

Fifty-three years ago today, NASA Astronaut Leroy Gordon Cooper successfully returned to the Earth following a 22-orbit mission. Designated Mercury-Atlas No. 9 (MA-9), Cooper’s flight was the last orbital space mission of the Mercury Program.

The final mission of the Mercury Program began with lift-off from Cape Canaveral, Florida at 13:04 hours GMT on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. Splashdown of Copper’s Faith 7 spacecraft occurred 70 miles southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, 16 May 1963. Mission total elapsed time was clocked at 34 hours 19-minutes 49-seconds.

While the first 19 orbits of the MA-9 mission were mostly unremarkable, the final three orbits severely tested Cooper’s mettle and piloting skills.

By the time that he manually initiated ripple-firing of the retro motors at the end of the 22nd orbit, Cooper was essentially flying a dead spacecraft. The electrical system was not functioning, the environmental control system was saturated with carbon dioxide, and even the mission clock was inoperative. Temperatures in the spacecraft exceeded 130F.

Cooper had to align his spacecraft for retro-fire using the horizon as a reference, used a watch for timing, and manually operated the reaction control system to counter dangerous spacecraft oscillations during the retro burn.

Cooper also manually controlled Faith 7 during entry and initiated deployment of the drogue and main parachutes.

Incredibly, Cooper landed within 5 miles of the recovery ship USS Kearsarge. In so doing, he established the record for the most accurate landing in the Mercury Program. Gordon Cooper was the last American astronaut to orbit the Earth alone.

Forty-three years ago this month, astronauts Pete Conrad, Joe Kerwin and Paul Weitz became the first NASA crew to fly aboard the recently-orbited Skylab space station. Not only would the crew establish a new record for time in orbit, they would effect critical repairs to America’s first space station which had been seriously damaged during launch.

Skylab was America’s first space station. The program followed closely on the heels of the historic Apollo lunar landing effort. Skylab provided the United States with a unique space platform for obtaining vast quantities of scientific data about the Earth and the Sun. It also served as a means for ascertaining the effects of long-duration spaceflight on human beings.

A Saturn IVB third stage served as Skylab’s core. This huge cylinder, which measured 48-feet in length and 22-feet diameter, was modified for human occupancy and was known as the Orbital Workshop (OWS). With the addition of a Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA) and Airlock Module (AM), Skylab had a total length of 83-feet.

Skylab was also outfitted with a powerful space observatory known as the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). This unit sat astride the MDA and was configured with a quartet of electricity-producing solar panels. The OWS had a pair of solar panels as well. The entire Skylab stack weighed 85 tons.

The Skylab space station (Skylab 1) was placed into a 270-mile orbit using a Saturn V launch vehicle on Monday, 14 May 1973. Upon reaching orbit, it quickly became apparent that all was far from well aboard the space station. The micro-meteoroid shield and solar panel on one side of the OWS had been lost during ascent. The other OWS solar panel was stuck and did not deploy as planned.

With the loss of an OWS solar panel, Skylab would not have enough electrical energy to conduct its mission. The station was also heating up rapidly (temperatures approached 190 F at one point). The lost micro-meteoroid shield also provided protection from solar heating. Sans this protection, internal temperatures could rise high enough to destroy food, medical supplies, film and other perishables and render the OWS uninhabitable.

NASA engineers quickly went to work developing fixes for Skylab’s problems. A mechanism was invented to free the stuck solar panel. A parasol of gold-plated flexible material, deployed from an OWS scientific airlock, was then fashioned and tested on the ground. This material would cover the exposed portion of the OWS and provide the needed thermal shielding.

The onus was now on the Skylab 2 crew of Conrad, Kerwin and Weitz to implement the requisite fixes in orbit. On Friday, 25 May 1973, the Skylab 2 crew and their Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) were rocketed into orbit by a Saturn IB launch vehicle. They quickly rendezvoused with Skylab and verified its sad condition. It was time to get to work.

The first order of business was to try to free the stuck solar panel. As Conrad flew the CSM in close proximity to Skylab, Kerwin held Weitz by the feet as the latter leaned out of the open CSM hatch and attempted to release the stuck solar panel with a pair of special cutters. No joy in spaceville. The solar panel refused to deploy.

The Skylab 2 crew next attempted to dock with Skylab. They tried six times and failed. The CSM drogue and probe was not functioning properly. The crew had to fix it or go home. With great difficulty, they did so and were finally able to dock with Skylab. The overriding objective now was to enter Skylab and successfully deploy the parasol thermal shield.

With Conrad remaining in the CSM, Kerwin and Weitz sported gas masks and cautiously entered Skylab. The temperature inside of the OWS was 130 F. Fortunately, the air was found to be of good quality and the pair went to work deploying the thermal shield through a scientific airlock. The deployment was successful and the temperature started to slowly fall.

It would not be until Thursday, 07 June 1973 that the stuck solar panel would finally be freed. On that occasion, Conrad and Kerwin donned EVA suits and spent 8 hours working outside of Skylab. Their initial efforts with the cutters were unsuccesful.

Undeterred, Conrad and Kerwin improvised and were able to cut the strap that restrained the solar panel. Then, heaving with all their might, the pair finally freed the solar panel. In obedience to Newton’s 3rd Law, as the solar panel deployed in one direction, the astronauts went flying in the other. Happily, they were able to collect themselves and safely reenter the now adequately-powered Skylab.

Skylab 2 went on to spend 28 days in orbits; a record for the time. This record was quickly eclipsed by the Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 crews which spent 59 and 84 days in space, respectively. Skylab was an unqualified success and provided a plethora of terrestrial, solar and human factors data of immense importance to space science. These data played a vital role in the design and development of the ISS.

Skylab was abandoned following the Skylab 4 mission in February of 1974. The plan was to reactivate it and raise its orbit using the Space Shuttle when the latter became operational. Unfortunately, a combination of a rapidly deteriorating orbit and delays in flying the Shuttle conspired against bringing this plan to fruition. Skylab reentered the Earth’s atmosphere and broke-up near Australia in July of 1979.

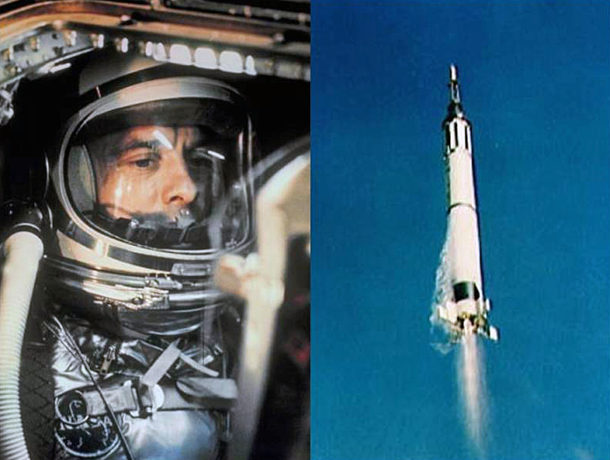

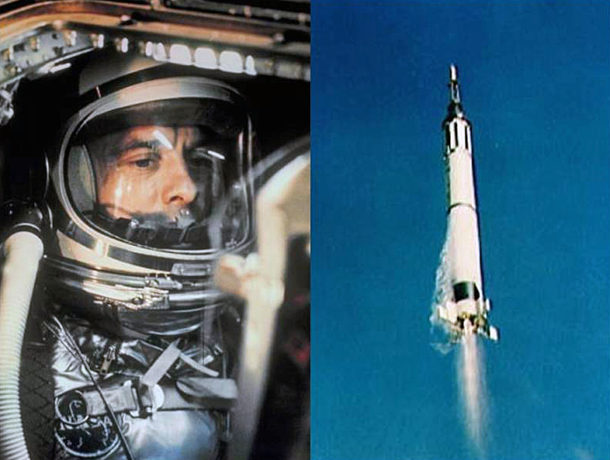

Fifty-five years ago this week, United States Navy Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became the first American to be launched into space. Shepard named his Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7.

Officially designated as Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) by NASA, the mission was America’s first true attempt to put a man into space. MR-3 was a sub-orbital flight. This meant that the spacecraft would travel along an arcing parabolic flight path having a high point of about 115 nautical miles and a total range of roughly 300 nautical miles. Total flight time would be about 15 minutes.

The Mercury spacecraft was designed to accommodate a single crew member. With a length of 9.5 feet and a base diameter of 6.5 feet, the vehicle was less than commodious. The fit was so tight that it would not be inaccurate to say that the astronaut wore the vehicle. Suffice it to say that a claustrophobic would not enjoy a trip into space aboard the spacecraft.

Despite its diminutive size, the 2,500-pound Mercury spacecraft (or capsule as it came to be referred to) was a marvel of aerospace engineering. It had all the systems required of a space-faring craft. Key among these were flight attitude, electrical power, communications, environmental control, reaction control, retro-fire package, and recovery systems.

The Redstone booster was an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) modified for the manned mission. The Redstone’s uprated A-7 rocket engine generated 78,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. Alcohol and liquid oxygen served as propellants. The Mercury-Redstone combination stood 83 feet in length and weighed 66,000 pounds at lift-off.

On Friday, 05 May 1961, MR-3 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 5 at 14:34:13 UTC. Alan Shepard went to work quickly calling out various spacecraft parameters and mission events. The astronaut would experience a maximum acceleration of 6.5 g’s on the ride upstairs.

Nearing apogee, Shepard manually controlled Freedom 7 in all 3 axes. In doing so, he positioned the capsule in the required 34-degree nose-down attitude. Retro-fire occurred ontime and the retro package was jettisoned without incident. Shepard then pitched the spacecraft nose to 14 degrees above the horizon preparatory to reentry into the earth’s atmosphere.

Reentry forces quickly built-up on the plunge back into the atmosphere with Shepard enduring a maximum deceleration of 11.6 g’s. He had trained for more than 12 g’s prior to flight. At 21,000 feet, a 6-foot droghue chute was deployed followed by the 63-foot main chute at 10,000 feet. Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 28 seconds after lift-off.

Following splashdown, Shepard egressed Freedom 7 and was retreived from the ocean’s surface by a recovery helicopter. Both he and Freedom 7 were safely onboard the carrier USS Lake Champlain within 11 minutes of landing. During his brief flight, Shepard had reached a maximum speed of 5,180 mph, flown as high as 116.5 nautical miles and traveled 302 nautical miles downrange.

The flight of Freedom 7 had much the same effect on the Nation as did Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927. However, in light of the Cold War fight against the world-wide spread of Soviet communism, Shepard’s flight arguably was more important. Indeed, Alan Shepard became the first of what Tom Wolfe called in his classic book The Right Stuff, the American single combat warrior.

For his heroic MR-3 efforts, Alan Shepard was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by an appreciative nation. In February 1971, Alan Shepard walked on the surface of the Moon as Commander of Apollo 14. He was the lone member of the original Mercury Seven astronauts to do so. Shepard was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Freedom in 1978.

Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia in July of 1998 at the age of 74. In tribute to this American space hero, naval aviator and US Naval Academy graduate, Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 spacecraft now resides in a place of honor at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Fifty-seven years ago this month, NASA held a press conference in Washington, D.C. to introduce the seven men selected to be Project Mercury Astronauts. They would become known as the Mercury Seven or Original Seven.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. The overall objective of Project Mercury was to place a manned spacecraft in Earth orbit and bring both man and machine safely home. Project Mercury ran from 1959 to 1963.

The men who would ultimately become Mercury Astronauts were among a group of 508 military test pilots originally considered by NASA for the new role of astronaut. The group of 508 candidates was then successively pared to 110, then 69 and finally to 32. These 32 volunteers were then subjected to exhaustive medical and psychological testing.

A total of 18 men were still under consideration for the astronaut role at the conclusion of the demanding test period. Now came the hard part for NASA. Each of the 18 finalists was truly outstanding and would be a worthy finalist. But there were only 7 spots on the team.

On Thursday, 09 April 1959, NASA publicly introduced the Mercury Seven in a special press conference held for this purpose at the Dolley Madison House in Washington, D.C. The men introduced to the Nation that day will forever hold the distinction of being the first official group of American astronauts. In the order in which they flew, the Mercury Seven were:

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr., United States Navy. Shepard flew the first Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-3) on Friday, 05 May 1961. He was also the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Shepherd did so as Commander of Apollo 14 (AS-509) in February 1971. Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia on 21 July 1998 at the age of 74.

Vigil Ivan Grissom, United States Air Force. Grissom flew the second Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-4) on Friday, 21 July 1961. He was also Commander of the first Gemini mission (GT-3) in March 1965. Gus Grissom might very well have been the first man to walk on the Moon. But he died in the Apollo 1 Fire, along with Astronauts Edward H. White II and Roger Chaffee, on Friday, 27 January 1967. Gus Grissom was 40 at the time of his death.

John Herschel Glenn Jr., United States Marines. Glenn was the first American to orbit the Earth (MA-6) on Thursday, 22 February 1962. He was also the only Mercury Astronaut to fly a Space Shuttle mission. He did so as a member of the STS-95 crew in October of 1998. Glenn was 77 at the time and still holds the distinction of being the oldest person to fly in space. John Glenn is the only living member of the Mercury Seven and will turn 95 in July 2016.

Malcolm Scott Carpenter, United States Navy. Carpenter became the second American to orbit the Earth (MA-7) on Thursday, 24 May 1962. This was his only mission in space. Carpenter subsequently turned his attention to under-sea exploration and was an aquanaut on the United States Navy SEALAB II project. Scott Carpenter died in October 2013 shortly after suffering a stroke. He was 88 at the time of his passing.

Walter Marty Schirra Jr., United States Navy. Schirra became the third American to orbit the Earth (MA-8) on Wednesday, 03 October 1962. He later served as Commander of Gemini 6A (GT-6) in December 1965 and Apollo 7 (AS-205) in October 1968. Schirra was the only Mercury Astronaut to fly Mercury, Gemini and Apollo space missions. Wally Schirra died from a heart attack in May 2007 at the age of 84.

Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr., United States Air Force. Cooper became the fourth American to orbit the Earth (MA-9) on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. In doing so, he flew the last and longest Mercury mission (22 orbits, 34 hours). Cooper was also Commander of Gemini 5 (GT-5), the first long-duration Gemini mission, in August 1965. Gordo Cooper died from heart failure in October 2004 at the age of 77.

Donald Kent Slayton, United States Air Force. Slayton was the only Mercury Astronaut to not fly a Mercury mission when he was grounded for heart arrythemia in 1962. He subsequently served many years on Gemini and Apollo as head of astronaut selection. He finally got his chance for spaceflight in July 1975 as a crew member of the Apollo-Soyuz mission (ASTP). Deke Slayton died from brain cancer in June of 1993 at the age of 69.

History records that the Mercury Seven was the only group of NASA astronauts that had a member that flew each of America’s manned spacecraft (i.e, Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Shuttle). Though just men and imperfect mortals, we honor and remember them for their genuinely heroic deeds and unique contributions made to the advancement of American manned spaceflight.

Seventy-three years ago this month, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most intriguing and haunting stories in the annals of aviation. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

Thirty-five years ago today, the United States successfully launched the Space Shuttle Columbia into orbit around the Earth. It was the maiden flight of the Nation’s Space Transportation System (STS).

The Space Shuttle was unlike any manned space vehicle ever flown. A giant aircraft known as the Orbiter was side-mounted on a huge liquid-propellant stage called the External Tank (ET). Flanking opposing sides of the ET was a pair of Solid Rocket Boosters (SRB). The Orbiter, SRB’s and ET measured 122 feet, 149 feet and 154 feet in length, respectively.

The Space Shuttle system was conceived with an emphasis on reusability. Each Orbiter (Columbia, Challenger, Atlantis, Discovery and Endeavor) was designed to fly 100 missions. Each SRB was intended for multiple mission use as well. The only single-use element was the ET since it was more cost effective to use a new one for each flight than to recover and refurbish a reusable version.

NASA called STS-1 the boldest test flight in history. Indeed, the STS-1 mission marked the first time that astronauts would fly a space vehicle on its inaugural flight! STS-1 was also the first time that a manned booster system incorporated solid rocket propulsion. Unlike liquid propellant rocket systems, once ignited, the Shuttle’s solid rockets burned until fuel exhaustion.

And then there was the Orbiter element which had its own new and flight-unproven propulsion systems. Namely, the Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME) and Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS). Each of the three (3) SSME’s generated 375,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. Thrust would increase to 475,000 pounds in vacuum. Each OMS rocket engine produced 6,000 pounds of thrust in vacuum.

The Orbiter was also configured with a reusable thermal protection system (TPS) which consisted of silica tiles and reinforced carbon-carbon material. The TPS for all previous manned space vehicles utilized single-use ablators. Would the new TPS work? How robust would it be in flight? What post-flight care would be needed? Answers would come only through flight.

To add to the “excitement” of first flight, the Orbiter was a winged vehicle and would therefore perform a hypersonic lifting entry. The vehicle energy state would have to be managed perfectly over the 5,000 mile reentry flight path from entry interface to runway touchdown. Since the Orbiter flew an unpowered entry, it would land dead-stick. There would only be one chance to land.

On Sunday,12 April 1981, the Space Shuttle Columbia lifted-off from Pad 39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Official launch time was 12:00:03 UTC. The flight crew consisted of Commander John W. Young and Pilot Robert L. Crippen. Their Columbia launch stack tipped the scales at 4.5 million pounds and thundered away from the pad on over 7 million pounds of thrust.

Columbia went through maximum dynamic pressure (606 psf) at Mach 1.06 and 26.5 KFT. SRB separation occurred 120 seconds into flight at Mach 3.88 and 174,000 feet; 10,000 feet higher than predicted. This lofting of the ascent trajectory was later attributed to unmodeled plume-induced aerodynamic effects in the Orbiter and ET base region.

Following separation, Columbia rode the ET to burnout at Mach 21 and 389.7 KFT. Following ET separation, Columbia’s OMS engines were fired minutes later to achieve a velocity of 17,500 mph and a 166-nautical mile orbit.

Young and Crippen would orbit the Earth 37 times before coming home on Tuesday, 14 April 1981. In doing so, they successfully flew the first hypersonic lifting reentry from orbit. Though unaware of it at the time, the crew came very close to catastrophe as the Orbiter’s body flap had to be deflected 8 degrees more than predicted to maintain hypersonic pitch control.

The reason for this “hypersonic anomaly” was that ground test and aero modeling had failed to capture the effects of high temperature gas dynamics on Orbiter pitch aerodynamics. Specifically, the vehicle was more stable in hypersonic flight than had been predicted. This necessitated greater nose-down body flap deflections to trim the vehicle in pitch. It was a close-call. But Columbia and its crew lived to fly another day.

Columbia touched-down at 220 mph on Runway 23 at Edwards Air Force Base, California at 18:20:57 UTC. Young and Crippen were euphoric with the against-the-odds success of the Space Shuttle’s first mission.

NASA too reveled in the Shuttle’s accomplishment. And so did America. This was the country’s first manned space mission since 1975. The longest period of manned spaceflight inactivity ever in the Nation’s history.

Fittingly, a well-known national news magazine celebrated Columbia’s success with a headline which read: “America is Back!”

And while it nor any of its stablemates fly no more, we remember with fondness that first Orbiter, its first flight, and its many subsequent accomplishments. To which we say: Hail Columbia!

Twenty-five years ago today, the Orbital Sciences Corporation (OSC) orbited a PegSat satellite using the then-new Pegasus 3-stage launch vehicle. This historic event marked the first successful implementation of the air-launched satellite launcher concept.

The concept of air-launch dates back to the 1940’s and the early days of United States X-plane flight research. A multi-engine aircraft known as the mothership was employed to transport a smaller test aircraft to altitude. The test aircraft was subsequently released from the mothership and went on to conduct the flight research mission.

A clear benefit of air-launch was that all of the fuel and propulsion required to get to the test aircraft drop point was provided by the mothership. Thus, the test aircraft was allowed to use all of its own fuel for the flight research mission proper. In that sense, the mothership-test aircraft combination functioned as a two-stage launch vehicle.

The value and efficacy of the air-launch concept was demonstrated on numerous X-plane programs. Flight research aircraft such as the Bell XS-1, Bell X-1A, Bell X-1E, Bell X-2, Douglas D-558-II, and North American X-15 were all air-launched. More recently, the X-43A and X-51A scramjet-powered flight research vehicles also employed the air-launch concept.

An added benefit of the air-launch technique is that the launch site is highly portable! This provides enhanced mission flexibility compared to fixed position launch sites. The associated operating costs are much lower for the air-launched concept as well.

Orbital Science’s original Pegasus launch vehicle configuration was designed to fit within the same dimensional envelope of the X-15. The standard Pegasus external configuration measured 50 feet in length and featured a wingspan of 22 feet. The same dimensions as the baseline X-15 rocket airplane. Pegasus body diameter and launch weight were 50 inches and 41,000 pounds, respectively.

A key design feature of the Pegasus 3-stage launch vehicle configuration was the vehicle’s trapezodal-planform wing which provided the aerodynamic lift required to shape the endoatmospheric portion of the ascent flight path. This made Pegasus even more like the X-15.

The defining difference between Pegasus and the X-15 was propulsion. The X-15 flew a sub-orbital trajectory using an XLR-99 liquid rocket engine rated at 57,000 pounds of sea level thrust. Pegasus employed a combination of three (3) Hercules solid rocket motors to perform an earth-orbital mission. The first, second and third stage rocket motors were rated at 109,000, 26,600 and 7,800 pounds of vacuum thrust, respectively.

On Thursday, 05 April 1990, the first Pegasus launch took place over the Pacific Ocean within an area known as the Point Arguello Western Air Drop Zone (WADZ) . Pegasus 001 fell away from its NASA B-52B (S/N 52-0008) mothership at 19:10 UTC as the pair flew at Mach 0.8 and 43,000 feet. Pegasus first stage ignition took place 5 seconds after drop.

Following first stage ignition, the Pegasus executed a pull-up to begin the trip upstairs. The second and third stage rocket motors fired on time. The stage separation and payload fairing jettison events worked as planned. Roughly 10 minutes after drop, the 392-pound PegSat payload arrived in a 315 mile x 249 mile elliptical orbit.

Since that triumphant day in April 1990, both the Pegasus launch vehicle configuration and mission have signifcantly grown and matured. Of a total of 42 official Pegasus orbital missions to date, 37 have been flown successfully.

Twelve years ago this month, the NASA X-43A scramjet-powered flight research vehicle reached a record speed of over 4,600 mph (Mach 6.83). The test marked the first time in the annals of aviation that a flight-scale scramjet accelerated an aircraft in the hypersonic Mach number regime.

NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X in 1996. The fundamental goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed nearly 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The second flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 27 March 2004. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 20:40 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 21:59:58 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership. Following a 5 second free fall, rocket motor ignition occurred and the HXLV initiated a pull-up to start its climb and acceleration to the test window. It took the HXLV about 90 seconds to reach a speed of slightly over Mach 7.

Following rocket motor burnout and a brief coast period, the HXRV (X-43A) successfully separated from the Pegasus booster at 94,069feet and Mach 6.95. The HXRV scramjet was operative by Mach 6.83. Supersonic combustion and thrust production were successfully achieved. Total power-on flight duration was approximately 11 seconds.

As the X-43A decelerated along its post-burn descent flight path, the aircraft performed a series of data gathering flight maneuvers. A vast quantity of high-quality aerodynamic and flight control system data were acquired for Mach numbers ranging from hypersonic to transonic. Finally, the X-43A impacted the Pacific Ocean at a point about 450 nautical miles due west of its launch location. Total flight time was approximately 15 minutes.

The HYPER-X Program made history that day in late March 2004. Supersonic combustion and thrust production of an airframe-integrated scramjet were achieved for the first time in flight; a goal that dated back to before the X-15 Program. Along the way, the X-43A established a speed record for airbreathing aircraft and earned a Guinness World Record for its efforts.

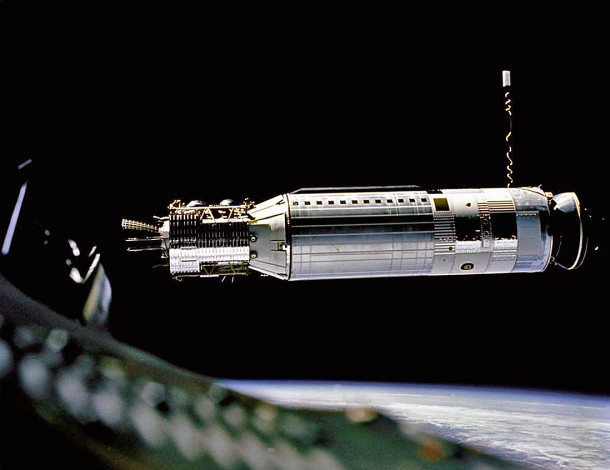

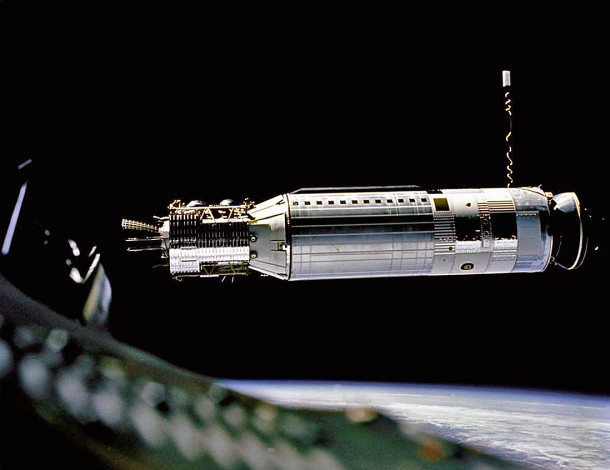

Fifty years ago this month, the crew of Gemini VIII successfully regained control of their tumbling spacecraft following failure of an attitude control thruster. The incident marked the first life-threatening on-orbit emergency and resulting mission abort in the history of Amercian manned spaceflight.

Gemini VIII was the sixth manned mission of the Gemini Program. The primary mission objective was to rendezvous and dock with an orbiting Agena Target Vehicle (ATV). Successful accomplishment of this objective was seen as a vital step in the Nation’s quest for landing men on the Moon.

The Gemini VIII crew consisted of Command Pilot Neil A. Armstrong and Pilot USAF Major David R. Scott. Both were space rookies. To them would go both the honor of achieving the first successful docking in orbit as well as the challenge of dealing with the first life and death space emergency involving an American spacecraft.

Gemini VIII lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 16:41:02 UTC on Wednesday, 16 March 1966. The crew’s job was to chase, rendezvous and then physically dock with an Agena that had been launched 101 minutes earlier. The Agena successfully achieved orbit and waited for Gemini VIII in a 161-nm circular Earth orbit.

It took just under six (6) hours for Armstrong and Scott to catch-up and rendezvous with the Agena. The crew then kept station with the target vehicle for a period of about 36 minutes. Having assured themselves that all was well with the Agena, the world’s first successful docking was achieved at a Gemini mission elasped time of 6 hours and 33 minutes.

Once the reality of the historic docking sank in, a delayed cheer erupted from the NASA and contractor team at Mission Control in Houston, Texas. Despite the complex orbital mechanics and delicate timing involved, Armstrong and Scott had actually made it look easy. Unfortunately, things were about to change with an alarming suddeness.

As the Gemini crew maneuvered the Gemini-Agena stack, their instruments indicated that they were in an uncommanded 30-degree roll. Using the Gemini’s Orbital Attiude and Maneuvering System (OAMS), Armstrong was able to arrest the rolling motion. However, once he let off the restoring thruster action, the combined vehicle began rolling again.

The crew’s next action was to turn off the Agena’s systems. The errant motion subsided. Several minutes elapsed with the control problem seemingly solved. Suddenly, the uncommanded motion of the still-docked pair started again. The crew noticed that the Gemini’s OAMS was down to 30% fuel. Could the problem be with the Gemini spacecraft and not the Agena?

The crew jettisoned the Agena. That didn’t help matters. The Gemini was now tumbling end over end at almost one revolution per second. The violent motion made it difficult for the astronauts to focus on the instrument panel. Worse yet, they were in danger of losing consciousness.

Left with no other alternative, Armstrong shut down his OAMS and activated the Reentry Control System reaction control system (RCS) in a desperate attempt to stop the dizzying tumble. The motion began to subside. Finally, Armstrong was able to bring the spacecraft under control.

That was the good news. The bad news for the crew of Gemini VIII was that the rest of the mission would now have to be aborted. Mission rules dictated that such would be the case if the RCS was activated on-orbit. There had to be enough fuel left for reentry and Gemini VIII had just enough to get back home safely.

Gemini VIII splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean 4,320 nm east of Okinawa. Mission elapsed time was 10 hours, 41 minutes and 26 seconds. Spacecraft and crew were safely recovered by the USS Leonard F. Mason.

In the aftermath of Gemini VIII, it was discovered that OAMS Thruster No. 8 had failed in the ON position. The probable cause was an electrical short. In addition, the design of the OAMS was such that even when a thruster was switched off, power could still flow to it. That design oversight was ultimately remediated so that subsequent Gemini missions would not be threatened by a reoccurence of the Gemini VIII anomaly.

Neil Armstrong and David Scott met their goliath in orbit and defeated the beast. Armstrong received a quality increase for his exceptional efforts on Gemini VIII while Scott was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Both men were also awarded the NASA Exceptional Service Medal.

More significantly, their deft handling of the Gemini VIII emergency elevated both Armstrong and Scott within the ranks of the astronaut corps. Indeed, each man would ultimately land on the Moon and serve as mission commander in doing so; Neil Armstrong on Apollo 11 and David Scott on Apollo 15.