Fifty-nine years ago today, the first flight test of a full-scale Lockheed X-7A ramjet test vehicle took place near Alamogordo, New Mexico. However, the dreaded flight test gremlins prevailed on this occasion as the entire X-7 launch stack disintegrated shortly after drop from its USAF B-29 launch aircraft.

The inauspicious start to the X-7 flight test program on Thursday, 26 April 1951 was but a momentary bump in the road. Ultimately, that road would lead to significant technological progress in the development of ramjet propulsion systems. Approximately 130 flight tests involving the X-7 would be conducted between 1951 and 1960.

The beginning of the X-7 program dates back to December of 1946. At that time, the United States was on the cusp of an unprecedented period of frontiersmanship in the realm of high-speed flight. Among other needs, a flying testbed was required to perform ramjet propulsion flight research.

A ramjet is a form of airbreathing propulsion well suited for flight up to a Mach number of about 5. Unlike the turbojet, a ramjet contains no internal rotating machinery. Flow compression comes entirely from deceleration of the supersonic freestream. However, a ramjet cannot produce static thrust. Hence, it must be boosted to flight speed via another propulsion system such as a turbojet or rocket.

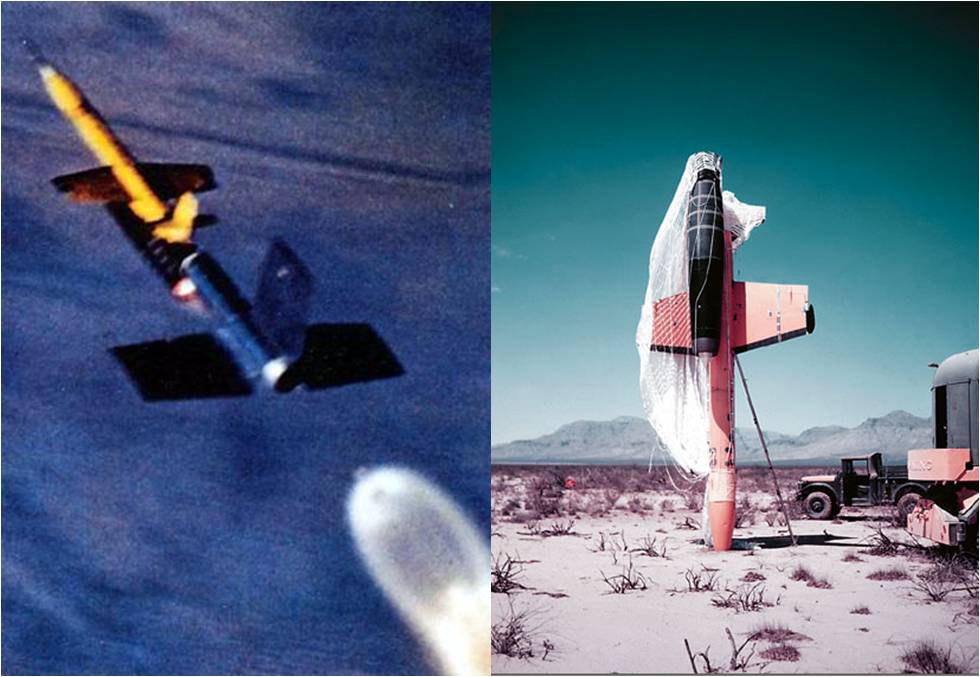

The X-7 was rocket-boosted to ramjet take-over conditions. Booster thrust was on the order of 100,000 pounds with a burn time of 5 seconds. Following booster separation, the type would fly on ramjet power until fuel exhaustion. The ramjet test article was slung under the belly of the X-7 airframe which made for an asymmetric vehicle configuration.

The entire X-7A-1 launch stack measured almost 33 feet in length and had a gross weight of about 8,000 pounds. Later variants such as the X-7A-3 and XQ-5 would be longer by 3 and 4 feet, respectively. However, their gross weight was about the same as that of the X-7A-1 configuration.

The X-7 was designed for reusability. Vehicle recovery was effected via a multi-segment parachute system. This feature afforded engineers the unique opportunity to make a post-flight inspection of each ramjet engine test article. These inspections of flight hardware made for a more reliable means of making needed propulsion system design improvements.

Typically, the X-7’s long conical nose penetrated several feet into the soil at landing. The result was that the X-7 airframe stuck out of the ground with the main parachute usually draped over the vehicle’s aft end. This somewhat comical operational feature made the X-7 much easier to locate on the floor of the vast desert test range.

The X-7 was utilized to flight test ramjet engines that ranged from 20 to 36 inches in diameter. Key propulsion performance data were telemetered to ground stations for post-flight analysis. The ability to test an assortment of ramjet engine configurations during many flights produced a wealth of ramjet propulsion data over the life of the X-7 program.

The X-7 established a variety of flight performance records during its heyday. The type’s airbreathing propulsion speed, altitude and range records included 2,880 mph (Mach 4.3), 106,000 feet and 134 miles, respectively. Note that these marks were all accomplished in the 1950’s.

The technological legacy of the X-7 program is impressive. Indeed, flight vehicles such as the Boeing BOMARC, Lockheed SR-71 and Lockheed D-21 were direct beneficiaries of X-7 propulsion flight research. Though difficult to assess the extent thereof, Lockheed’s legendary Advanced Development Program (i.e., Skunk Works) has undoubtably benefitted from the X-7’s rich propulsion legacy as well.