Sixty-two years ago this week, USAF Major William F. “Pete” Knight made an emergency landing in X-15 No. 1 at Mud Lake, Nevada. Knight somehow managed to save the hypersonic aircraft following a complete loss of electrical power as the vehicle passed through 107,000 feet during the climb.

The famed X-15 Program conducted 199 flights between June 1959 and October 1968. North American Aviation (NAA) built three (3) X-15 aircraft. Twelve (12) men from NAA, USAF and NASA flew the X-15. Eight (8) pilots received astronaut wings for flying the X-15 beyond 250,000 feet. One (1) aircraft and one (1) pilot were lost during flight test.

The X-15 flew as fast as 4,520 mph (Mach 6.7) and as high as 354,200 feet. The basic airframe measured 50 feet in length, featured a wing span of 22 feet and had a gross weight of 33,000 pounds. The type’s Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine burned anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen to produce a sea level thrust of 57,000 pounds. The X-15 used both 3-axis aerodynamic and ballistic flight controls.

An X-15 mission was fast-paced. Flight time from B-52 drop to unpowered landing was typically 10 to 12 minutes in duration. The pilot wore a full pressure suit and experienced 6 to 7 G’s during pull-out from max altitude. There really was no such thing as a routine X-15 mission. However, all X-15 missions had one factor in common; high danger.

On Thursday, 29 June 1967, X-15 No. 1 (S/N 56-6670) made its 73rd and the X-15 Program’s 184th free flight. Launch took place at 1828 UTC as the NASA B-52B launch aircraft (S/N 52-0008) flew at Mach 0.82 and 40,000 feet near Smith Ranch, Nevada. Knight, making his 10th X-15 flight, quickly ignited the XLR-99 and started the climb upstairs.

The X-15 was performing well and Knight was enjoying the flight until 67.6 seconds into a planned 87 second XLR-99 burn. That’s when the engine suddenly quit. A couple of heartbeats later, the Stability Augmentation System (SAS) failed, the Auxiliary Power Units (APU’s) ceased operating, the X-15’s generators stopped functioning and the cockpit lights went out. This was the total hit; a complete power failure.

Pete Knight was now just along for the ride. No thrust to power the aircraft. No electrical power to run onboard systems. No hydraulics to move flight controls. Even the reaction controls appeared inoperative. The X-15 continued upward, but it wallowed aimlessly in the low dynamic pressure of high altitude flight. At this point, Knight considered taking his chances and punching-out.

The X-15 went over the top at 173,000 feet. On the way downhill, Knight was able to get some electrical power from the emergency battery. This meant that he now had some hydraulic power and could utilize the X-15’s flight control surfaces. Knight next tried to fire-up the APU’s. The right APU would not respond. The left APU fired, but the its generator would not engage.

As the X-15 descended and the dynamic pressure built-up, Knight was able to maneuver his stricken X-15. He headed for Mud Lake in a sustained 6-G turn. As he leveled off at 45,000 feet, Knight instinctively knew he could now make the east shore of the Nevada dry lake. But it was tough work to fly the X-15. Knight ended-up using both hands to fly the airplane; one hand on the side stick and one hand on the center stick.

While Knight was trying to get his airplane down on the ground in one piece, only he and his Maker knew his whereabouts. The X-15 flight test team certainly didn’t, since Knight’s radio, telemetry and radar transponder were now inop. Further, the X-15 was not being skinned tracked at the time of the electrical anomaly. Just before he touched-down at Mud Lake, Knight’s X-15 was spotted by NASA’s Bill Dana who was flying a F-104N chase aircraft.

Pete Knight made a good landing at Mud Lake. The X-15 slid to a stop. After a struggle with the release mechanism, he managed to get the canopy open. Hot and soaked with perspiration, Knight somehow removed his own helmet. A ground crewman usually did that for him. But there were no flight support people at his X-15 landing site on this day.

As he attempted to get out of the X-15 cockpit, Knight pulled an emergency release. To his surprise, the headrest blew off, bounced off the canopy and smacked him square in the head. Undeterred, Knight got out of the cockpit and onto terra firma. In the meantime, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules had landed at Mud Lake. Wearily, Pete Knight got onboard and returned to Edwards Air Force Base.

Post-flight investigation revealed that the most probable source of the X-15’s electrical failure was arcing in a flight experiment system. This system had been connected to the X-15’s primary electrical bus. The solution was to connect flight experiments to the secondary electrical bus.

Reflecting on Knight’s amazing recovery from almost certain disaster, long-time NASA flight test manager Paul Bickle claimed the fete was among the most impressive of the X-15 Program. Indeed, it was Pete Knight’s clearly uncommon piloting skill and poise under pressure that gave him the edge.

Sixty-one years ago this month, the United States Army Nike Hercules air defense missile system was first deployed in the continental United States. The second-generation surface-to-air missile was designed to intercept and destroy hostile ballistic missiles.

The Nike Program was a United States Army project to develop a missile capable of defending high priority military assets and population centers from attack by Soviet strategic bombers. Named for the Greek goddess of victory, the Nike Program began in 1945. The industrial consortium of Bell Laboratories, Western Electric, Hercules and Douglas Aircraft developed, tested and fielded Nike for the Army.

Nike Ajax (MIM-3) was the first defensive missile system to attain operational status under the Nike Program. The two-stage, surface-launched interceptor initially entered service at Fort Meade, Maryland in December of 1953. A total of 240 Nike Ajax launch sites were eventually established throughout CONUS. The primary assets protected were metropolitan areas, long-range bomber bases, nuclear plants and ICBM sites.

Nike Ajax consisted of a solid-fueled first stage (59,000 lbs thrust) and a liquid-fueled second stage (2,600 lbs thrust). The launch vehicle measured nearly 34 feet in length and had a ignition weight of 2,460 lbs. The second stage was 21 feet long, had a maximum diameter of 12 inches and weighed 1,150 lbs fully loaded. The type’s maximum speed, altitude and range were 1,679 mph, 70,000 feet and 21.6 nautical miles, respectively.

The Nike Hercules (MIM-14) was the successor to the Nike Ajax. It featured all-solid propulsion and much higher thrust levels. The first stage was rated at 220,000 lbs of thrust while that of the second stage was 10,000 lbs. The Nike Hercules airframe was significantly larger than its predecessor. The launch vehicle measured 41 feet in length and weighed 10,700 lbs at ignition. Second stage length and ignition weight were 26.8 feet and 5,520 lbs, respectively.

Nike Hercules kinematic performance was quite impressive. The respective top speed, altitude and range were 3,000 mph, 150,000 feet and 76 nautical miles. This level of performance allowed the vehicle to be used for the ballistic missile intercept mission. Most Nike Hercules missiles carried a nuclear warhead with a yield of 20 kilotons.

The first operational Nike Hercules systems were deployed to the Chicago, Philadelphia and New York localities on Monday, 30 June 1958. By 1963, fully 134 Nike Hercules batteries were deployed throughout CONUS. These systems remained in the United States missile arsenal until 1974. The exceptions were batteries located in Alaska and Florida which remained in active service until the 1978-79 time period.

Like Nike Ajax before it, Nike Hercules had a successor. It was originally known as Nike Zeus and then Nike-X. This Nike variant was designed for intercepting enemy ICBM’s that were targeted for American soil. The vehicle went through a number of iterations before a final solution was achieved. Known as Spartan, this missile was what we would refer to today as a mid-course interceptor.

In companionship with a SPRINT terminal phase interceptor, Spartan formed the Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile System. The American missile defense system was impressive enough to the Soviet Union that the communist country signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty 3 years before Safeguard’s deployment. Though operational for a mere 3 months, Safeguard was de-postured in 1975. This action brought to a close a 30-year period in which the Nike Program was a major player in American missile defense.

Sixty-one years ago this month, the USN/Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III interceptor prototype took off on its maiden test flight at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Vought chief test pilot John W. Konrad was at the controls of the advanced high performance aircraft.

The Vought XF8U-3 was designed to intercept and defeat adversary aircraft. Although it bore a close external resemblance to its F8U-1 and F8U-2 forbears, the XF8U-3 was much more than just a block improvement in the Crusader line. It was considerably bigger, faster, and more capable than previous Crusaders and was in reality a new airplane.

The XF8U-3 measured 58.67 feet in length and had a wing span of an inch less than 40 feet. Gross Take-Off and empty weights tipped the scales at 38,770 lbs and 21,860 lbs, respectively. Power was provided by a single Pratt and Whitney J75-P-5A generating 29,500 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner.

A distinctive feature of the XF8U-3 was a pair of ventrally-mounted vertical tails. These surfaces were installed to improve aircraft directional stability at high Mach number. Retracted for take-off and landing, the surfaces were deployed once the aircraft was in flight.

The No. 1 XF8U-3 (S/N 146340) first flew on Monday, 02 June 1958 at Edwards Air Force, California. Vought chief test pilot John W. Konrad did the first flight piloting honors. The aircraft flew well with no major discrepancies reported. Approach and landing back at Edwards were uneventful.

Subsequent flight testing verified that the XF8U-3 was indeed a hot airplane. The type reached a top speed of Mach 2.39 and could have flown faster had its canopy had been designed for higher temperatures. The flight test-determined absolute altitude of 65 KFT was exceeded by 25 KFT in a zoom climb.

Those who flew the XF8U-3 said that the aircraft was a real thrill to fly. The Crusader III displayed outstanding acceleration, maneuverability and high-speed flight stability. Control harmony in pitch, yaw, and roll was extremely good as well.

Despite its great promise, the XF8U-3 never proceeded to production. This was primarily the result of coming up short in a head-to-head competition with the McDonnell F4H-1 Phantom II during the second half of 1958. While the Crusader was faster and more maneuverable than the Phantom, the latter’s mission capability and payload capacity were better.

Most historical records indicate that a total of five (5) Crusader III airframes were built. The serial numbers assigned by the Navy were 146340, 146341, 147085, 147086, and 147087. None of these aircraft exist today.

Fifty-three years ago today, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) and a NASA F-104N Starfighter (N813NA) were destroyed following a midair collision near Bartsow, CA. USAF Major Carl S. Cross and NASA Chief Test Pilot Joseph A. Walker perished in the tragedy.

On Wednesday, 08 June 1966, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time. The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final flight in the majestic Valkyrie.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful day, the mission was a simple one; some minor flight research test points and a photo shoot.

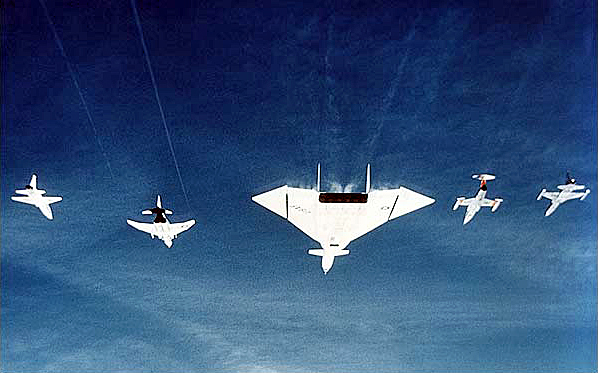

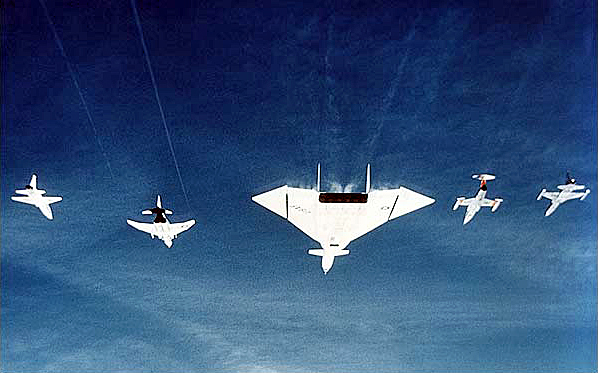

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The mishap formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A Talon (59-1601), an F-4B Phantom II (BuNo 150993), an F-104N Starfighter (N813NA), and an F-5A Freedom Fighter (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet Citation (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control Starfighter then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker died instantly in the terrifying process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed Valkyrie torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the stricken aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) responsibility (blame) for the mishap was assigned and new procedures implemented. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards Air Force Base, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that was, in the final analysis, preventable.

Fifty-four years ago this month, Gemini Astronaut Edward H. White II became the first American to perform what in NASA parlance is referred to as an Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA). In everyday terms, it is referred to as a “spacewalk”.

White, Mission Commander James A. McDivitt and their Gemini spacecraft were launched into low Earth orbit by a two-stage Titan II launch vehicle from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. The Gemini-Titan IV (GT-4) mission clock started at 15:15:59 UTC on Thursday, 03 June 1965.

On the third orbit, less than five hours after launch, White opened the Gemini IV starboard hatch. He stood in his seat and mounted a camera to capture his historic space stroll. He then cast-off from Gemini IV and became a human satellite.

White was tethered to Gemini IV via a 15-foot umbilical that provided oxygen and communications to his EVA suit. A gold-plated visor on his helmet protected his eyes from the searing glare of the sun. The spacewalking astronaut was also outfitted with a hand-held maneuvering unit that used compressed oxygen to power its small thrusters. And, like any good tourist, White also took along a camera to photograph the event.

Ed White had the time of his all-too-brief life in the 22 minutes that he walked in space. The sight of the earth, the spacecraft, the sun, the vastness of space, the freedom of movement all combined to make him excitedly exclaim at one point, “I feel like a million dollars!”.

Presently, it was time to get back into the spacecraft. But, couldn’t he just stay outside a little longer? NASA Mission Control and Commander McDivitt were firm. It was time to get back in; now! He grudgingly complied with the request/order, plaintively lamenting: “It’s the saddest moment of my life!”

As Ed White got back into his seat, he and McDivitt struggled to lock the starboard hatch. Both men were exhausted, but ebullient as they mused about the successful completion of America’s first space walk.

Gemini IV would eventually orbit the Earth 62 times before splashing-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 17:12:11 GMT on Sunday, 07 June 1965. The 4-day mission was another milestone in America’s quest for the moon.

The mission was over and yet Ed White was still a little tired. But then, that was really quite easy to understand. In the time that he was spacewalking outside the spacecraft, Gemini IV had traveled almost a third of the way around the Earth.

Fifty-eight years ago today, President John F. Kennedy boldly proposed that the United States achieve a manned lunar landing before the end of the 1960’s. The President’s clarion call to glory was delivered during a special session of the United States Congress which focused on what he called “urgent national needs”.

The transcript of that historic speech given on Friday, 25 May 1962 indicates that the ninth and last issue addressed by President Kennedy was simply entitled SPACE. The most stirring and memorable words of that portion of the 35th President’s long ago address to the nation may well be these:

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Although he did not live to see the fulfillment of that monumental goal, history records that 8 years, 1 month, and 26 days later, the United States of America indeed landed men on the moon and returned them safely to the earth before the decade of the 1960’s was concluded. Indeed, this feat was accomplished twice before decade’s end; Apollo 11 (July 1969) and Apollo 12 (November 1969).

Fifty-one years ago this month, NASA Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong narrowly escaped with his life when he was forced to eject from the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle in which he was training. Armstrong punched-out only 200 feet above ground level and spent just 4 seconds in the silk before safely landing.

The Lunar Module (LM) was the vehicle used by Apollo astronauts to land on and depart from the lunar surface. This unique spacecraft consisted of separate descent and ascent rocket-powered stages. The powered descent phase was initiated at 50,000 feet AGL and continued all the way to landing. The powered ascent phase lasted from lunar lift-off to 60,000 feet AGL.

It was recognized early in the Apollo Program that landing a spacecraft on the lunar surface under vacuum conditions would be very challenging to say the least. To maximize their chances for doing so safely, Apollo astronauts would need piloting practice prior to a lunar landing mission. And they would need an earth-bound vehicle that flew like the LM to get that practice.

The Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) was the answer to the above. The LLRV employed a turbojet engine that provided vertical thrust to cancel five-sixths of its weight since the gravity on the Moon is one-sixth that of Earth. The vehicle was also configured with dual lift rockets to provide vertical and horizontal motion. LLRV 3-axis attitude control was provided by a series of 16 small thrusters.

The LLRV was described by one historical NASA document as being “unconventional, contrary and ugly”. Known as the “Flying Bedstead”, the LLRV was designed for the specific purpose of simulating LM flight during the terminal phase of a lunar landing. The LLRV was not easy to fly in the “low and slow” flight regime in which it operated. The type was aesthetically unattractive in the extreme.

A pair of LLRV’s were constructed by Bell Aerosystems and flight tested at what is now the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center starting in October 1964. These vehicles were subsequently shipped to Ellington Air Force Base in Texas by early 1967. A number of flight crew, including Neil Armstrong, began LLRV flight training shortly thereafter.

Neil Armstrong made his first LLRV flight on Monday, 27 March 1967 in LLRV No. 1. (This occurred two months after the horrific Apollo 1 Fire.) Armstrong continued flight training in the LLRV over the next year in preparation for what would ultimately be the first manned lunar landing attempt in July of 1969

On Monday, 06 May 1968, Armstrong was flying LLRV No. 1 when the vehicle began losing altitude as its lift rockets lost thrust. Using turbojet power, Armstrong was able to get the LLRV to climb. As he did so, the vehicle made an uncommanded pitch-up and roll over. The attitude control system was unresponsive. The pilot had no choice but to eject.

Neil Armstrong ejected from the LLRV at 200 feet AGL as LLRV No. 1 crashed to destruction. The pilot was subjected to an acceleration of 14 G’s as his rocket-powered, vertically-seeking ejection seat functioned as designed. Armstrong got a full chute, but made only a few swings in same before safely touching-down back on terra firma. His only injury was to his tongue, which he accidently bit at the moment of ejection seat rocket motor ignition.

A mishap investigation board attributed the LLRV mishap to a design deficiency that allowed the helium gas pressurant of the lift rocket and attitude control system fuel tanks to be be accidently depleted. Thus, propellants could not be delivered to the lift rockets and attitude control system thrusters.

Neil Armstrong and indeed all of the Apollo astronauts who landed on the Moon trained in improved variants of the LLRV known as the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV). This training was absolutely crucial to the success of the half-dozen Apollo crews who landed on the Moon. Indeed, there was no other way to adequately simulate moon landings except by flying the LLTV.

Forty-six years ago this month, astronauts Pete Conrad, Joe Kerwin and Paul Weitz became the first NASA crew to fly aboard the recently-orbited Skylab space station. Not only would the crew establish a new record for time in orbit, they would effect critical repairs to America’s first space station which had been seriously damaged during launch.

Skylab was America’s first space station. The program followed closely on the heels of the historic Apollo lunar landing effort. Skylab provided the United States with a unique space platform for obtaining vast quantities of scientific data about the Earth and the Sun. It also served as a means for ascertaining the effects of long-duration spaceflight on human beings.

A Saturn IVB third stage served as Skylab’s core. This huge cylinder, which measured 48-feet in length and 22-feet diameter, was modified for human occupancy and was known as the Orbital Workshop (OWS). With the addition of a Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA) and Airlock Module (AM), Skylab had a total length of 83-feet.

Skylab was also outfitted with a powerful space observatory known as the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). This unit sat astride the MDA and was configured with a quartet of electricity-producing solar panels. The OWS had a pair of solar panels as well. The entire Skylab stack weighed 85 tons.

The Skylab space station (Skylab 1) was placed into a 270-mile orbit using a Saturn V launch vehicle on Monday, 14 May 1973. Upon reaching orbit, it quickly became apparent that all was far from well aboard the space station. The micro-meteoroid shield and solar panel on one side of the OWS had been lost during ascent. The other OWS solar panel was stuck and did not deploy as planned.

With the loss of an OWS solar panel, Skylab would not have enough electrical energy to conduct its mission. The station was also heating up rapidly (temperatures approached 190 F at one point). The lost micro-meteoroid shield also provided protection from solar heating. Sans this protection, internal temperatures could rise high enough to destroy food, medical supplies, film and other perishables and render the OWS uninhabitable.

NASA engineers quickly went to work developing fixes for Skylab’s problems. A mechanism was invented to free the stuck solar panel. A parasol of gold-plated flexible material, deployed from an OWS scientific airlock, was then fashioned and tested on the ground. This material would cover the exposed portion of the OWS and provide the needed thermal shielding.

The onus was now on the Skylab 2 crew of Conrad, Kerwin and Weitz to implement the requisite fixes in orbit. On Friday, 25 May 1973, the Skylab 2 crew and their Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) were rocketed into orbit by a Saturn IB launch vehicle. They quickly rendezvoused with Skylab and verified its sad condition. It was time to get to work.

The first order of business was to try to free the stuck solar panel. As Conrad flew the CSM in close proximity to Skylab, Kerwin held Weitz by the feet as the latter leaned out of the open CSM hatch and attempted to release the stuck solar panel with a pair of special cutters. No joy in spaceville. The solar panel refused to deploy.

The Skylab 2 crew next attempted to dock with Skylab. They tried six times and failed. The CSM drogue and probe was not functioning properly. The crew had to fix it or go home. With great difficulty, they did so and were finally able to dock with Skylab. The overriding objective now was to enter Skylab and successfully deploy the parasol thermal shield.

With Conrad remaining in the CSM, Kerwin and Weitz sported gas masks and cautiously entered Skylab. The temperature inside of the OWS was 130 F. Fortunately, the air was found to be of good quality and the pair went to work deploying the thermal shield through a scientific airlock. The deployment was successful and the temperature started to slowly fall.

It would not be until Thursday, 07 June 1973 that the stuck solar panel would finally be freed. On that occasion, Conrad and Kerwin donned EVA suits and spent 8 hours working outside of Skylab. Their initial efforts with the cutters were unsuccesful.

Undeterred, Conrad and Kerwin improvised and were able to cut the strap that restrained the solar panel. Then, heaving with all their might, the pair finally freed the solar panel. In obedience to Newton’s 3rd Law, as the solar panel deployed in one direction, the astronauts went flying in the other. Happily, they were able to collect themselves and safely reenter the now adequately-powered Skylab.

Skylab 2 went on to spend 28 days in orbits; a record for the time. This record was quickly eclipsed by the Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 crews which spent 59 and 84 days in space, respectively. Skylab was an unqualified success and provided a plethora of terrestrial, solar and human factors data of immense importance to space science. These data played a vital role in the design and development of the ISS.

Skylab was abandoned following the Skylab 4 mission in February of 1974. The plan was to reactivate it and raise its orbit using the Space Shuttle when the latter became operational. Unfortunately, a combination of a rapidly deteriorating orbit and delays in flying the Shuttle conspired against bringing this plan to fruition. Skylab reentered the Earth’s atmosphere and broke-up near Australia in July of 1979.

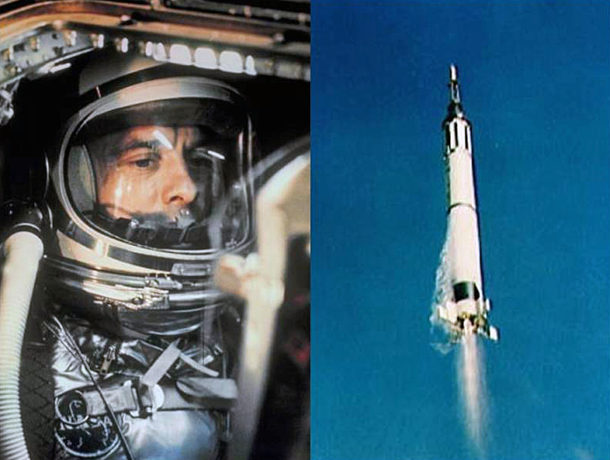

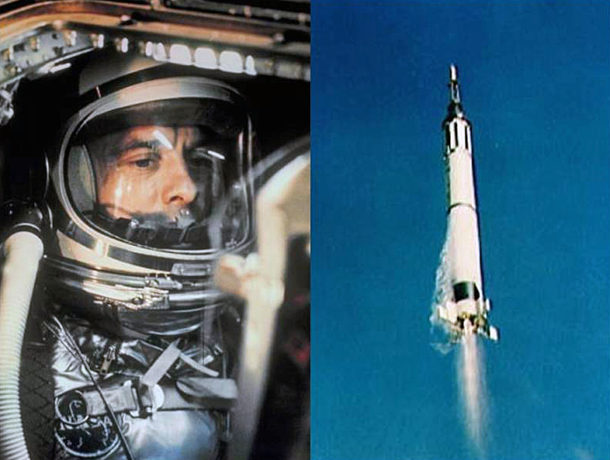

Fifty-eight years ago this month, United States Navy Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became the first American to be launched into space. Shepard named his Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7.

Officially designated as Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) by NASA, the mission was America’s first true attempt to put a man into space. MR-3 was a sub-orbital flight. This meant that the spacecraft would travel along an arcing parabolic flight path having a high point of about 115 nautical miles and a total range of roughly 300 nautical miles. Total flight time would be about 15 minutes.

The Mercury spacecraft was designed to accommodate a single crew member. With a length of 9.5 feet and a base diameter of 6.5 feet, the vehicle was less than commodious. The fit was so tight that it would not be inaccurate to say that the astronaut wore the vehicle. Suffice it to say that a claustrophobic would not enjoy a trip into space aboard the spacecraft.

Despite its diminutive size, the 2,500-pound Mercury spacecraft (or capsule as it came to be referred to) was a marvel of aerospace engineering. It had all the systems required of a space-faring craft. Key among these were flight attitude, electrical power, communications, environmental control, reaction control, retro-fire package, and recovery systems.

The Redstone booster was an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) modified for the manned mission. The Redstone’s up-rated A-7 rocket engine generated 78,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. Alcohol and liquid oxygen served as propellants. The Mercury-Redstone combination stood 83 feet in length and weighed 66,000 pounds at lift-off.

On Friday, 05 May 1961, MR-3 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 5 at 14:34:13 UTC. Alan Shepard went to work quickly calling out various spacecraft parameters and mission events. The astronaut would experience a maximum acceleration of 6.5 g’s on the ride upstairs.

Nearing apogee, Shepard manually controlled Freedom 7 in all 3 axes. In doing so, he positioned the capsule in the required 34-degree nose-down attitude. Retro-fire occurred on-time and the retro package was jettisoned without incident. Shepard then pitched the spacecraft nose to 14 degrees above the horizon preparatory to reentry into the earth’s atmosphere.

Reentry forces quickly built-up on the plunge back into the atmosphere with Shepard enduring a maximum deceleration of 11.6 g’s. He had trained for more than 12 g’s prior to flight. At 21,000 feet, a 6-foot drogue chute was deployed followed by the 63-foot main chute at 10,000 feet. Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 28 seconds after lift-off.

Following splashdown, Shepard egressed Freedom 7 and was retrieved from the ocean’s surface by a recovery helicopter. Both he and Freedom 7 were safely onboard the carrier USS Lake Champlain within 11 minutes of landing. During his brief flight, Shepard had reached a maximum speed of 5,180 mph, flown as high as 116.5 nautical miles and traveled 302 nautical miles downrange.

The flight of Freedom 7 had much the same effect on the Nation as did Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927. However, in light of the Cold War fight against the world-wide spread of Soviet communism, Shepard’s flight arguably was more important. Indeed, Alan Shepard became the first of what Tom Wolfe called in his classic book The Right Stuff, the American single combat warrior.

For his heroic MR-3 efforts, Alan Shepard was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by an appreciative nation. In February 1971, Alan Shepard walked on the surface of the Moon as Commander of Apollo 14. He was the lone member of the original Mercury Seven astronauts to do so. Shepard was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Freedom in 1978.

Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia in July of 1998 at the age of 74. In tribute to this American space hero, naval aviator and US Naval Academy graduate, Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 spacecraft now resides in a place of honor at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Forty-eight years ago this month, the crew of Apollo 13 departed Earth and headed for the Fra Mauro highlands of the Moon. Less than six days later, they would be back on Earth following an epic life and death struggle to survive the effects of an explosion that rocked their spacecraft 200,000 miles from home.

Apollo 13 was slated as the 3rd lunar landing mission of the Apollo Program. The intended landing site was the mountainous Fra Mauro region near the lunar equator. The Apollo 13 crew consisted of Commander James A. Lovell, Jr., Lunar Module Pilot Fred W. Haise, Jr. and Command Module Pilot John L. (Jack) Swigert, Jr. Lovell was making his fourth spaceflight (second to the Moon) while Haise and Swigert were space rookies.

Apollo 13 lifted-off from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, 11 April 1970. The official launch time was 19:13:00 UTC (13:13 CST). During second stage burn, the center engine shutdown two minutes early as a result of excessive longitudinal structural vibrations. The outer four J-2 engines burned 34 seconds longer to compensate. Arriving safely in low Earth orbit, Lovell observed that every mission seemed to have at least one major glitch. Clearly, Apollo 13′s was now out of the way!

The Apollo 13 payload stack consisted of a Command Module (CM), Service Module (SM) and Lunar Module (LM). The entire ensemble had a lift-off mass of nearly 49 tons. In keeping with tradition, the Apollo 13 crew gave call signs to their Command Module and Lunar Modules. This helped flight controllers distinguish one vehicle from the other over the communications net during mission operations. The CM was named Odyssey and the LM was given the name of Aquarius.

The first two days of the outward journey to the Moon were uneventful. In fact, some at Mission Control in Houston, Texas seemed somewhat bored. The same could be said for the ever-astute press corps who predictably reported that Americans were now responding to the lunar landing missions with a collective yawn. The journalistic sages averred that the space program needed some pepping-up. Going to the Moon might have been impossible yesterday, but today its just run-of-the-mill stuff. Actually, it was all kind of easy. So wrote they of the fickle Fourth Estate.

It all started with a bang at 03:07:53 UTC on Tuesday, 14 April 1970 (21:07:53 CST, 13 April 1970) with Apollo 13 distanced 200,000 miles from Earth. “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” This terse statement from Jack Swigert informed Mission Control that something ominous had just occurred onboard Apollo 13. Jim Lovell reported that the problem was a “Main B Bus undervolt”. A potentially serious electrical system problem.

But what was the exact nature of the of problem and why did it occur? Nary a soul in the spacecraft nor in Mission Control could provide the answers. All anyone really knew at the moment was that two of three fuel cells formerly supplying electricity to the Command Module were now dead. Arguably more alarming, Oxygen Tank No. 2 was empty with Tank No. 1 losing oxygen at a high rate.

There was something else. The Apollo 13 reaction control system was firing in apparent response to some perturbing influence. But what was it? The answer came with all the subtlety of a sledge hammer blow. Jim Lovell reported that some kind of gas was venting from the spacecraft into space. That chilling observation suddenly explained why the No. 1 oxygen tank was losing pressure so rapidly.

Once Mission Control and the Apollo 13 astronauts fully comprehended the gravity of the situation, the entire team went to work to bring the spacecraft home. Odyssey was powered-down to conserve its battery power for reentry while Aquarius was powered-up and became a makeshift lifeboat. A major problem was that Aquarius had battery power and water sufficient for only 40 hours of flight. The trip home would take 90 hours.

Amazingly, engineering teams at Mission Control conceived and tested means to minimize electrical usage onboard Aquarius. However, the Apollo 13 crew would have to endure privation and hardships to survive. The cabin temperature in Aquarius got down to 38F and each man was permitted only six ounces of water per day. The walls of the spacecraft were covered with condensation. Sleep was almost impossible and fatigue became another relentless enemy to survival.

And then there was the build-up of carbon dioxide. The LM environmental system (EV) was designed to support two men. Now there were three. Between the CM and LM, there was an ample supply of lithium hydroxide canisters to scrub the gas from the cabin atmosphere for the trip home. However, the square CM canisters were incompatible with the circular openings on LM EV. The engineers on the ground invented a device to eliminate this compatibility using materials found onboard the spacecraft.

The Apollo 13 crew had to fire the LM descent motor several times in order to adjust their return trajectory. Use of the SM propulsion system to effect these firings was denied the crew due to concerns that the explosion could have damaged it. These rocket motor firings required precise inertial navigation. The star sightings required for celestial navigation were impossible to make owing to the huge cloud of debris surrounding the spacecraft. Means were devised to use the Sun as the primary navigational source.

While the nation and indeed the world looked on, the miracle of Apollo 13 slowly unfolded. Many a humble heart uttered a prayer for and in behalf of the trio of astronauts. Millions throughout the world followed the men’s journey home via newspaper, radio, television and other media.

As Apollo 13 approached the Earth, the overriding issue was whether the systems onboard Odyssey could be successfully brought back on line. The walls and instrument panels of the craft were drenched with condensation. Unquestionably, the electronics and wiring bundles behind those instrument panels were also soaking wet. Would they short-out once electrical energy flowed through them again? Would there be enough battery power for reentry?

Happily, the CM power-up sequence was successfully accomplished. Once again the resourceful engineers at Mission Control produced under extreme duress. They devised an intricate and never-attempted-in-flight power-up sequence for the CM. Too, the extra insulation added to the CM’s electrical system in the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire provided protection from condensation-induced electrical arcing.

Approximately four hours prior to reentry, the Apollo 13 crew jettisoned the SM. What they saw was shocking. The module was missing a complete external panel and most of the equipment inside was gone or significantly damaged. One hour prior to entry, Aquarius, their trusty space lifeboat, was also jettisoned. The only concern now was whether the Command Module base heat shield had survived the explosion intact.

On Friday, 17 April 1970, Odyssey hit entry interface (400,000 feet) at 36,000 feet per second. Other than a worrisome additional 33 seconds of plasma-induced communications blackout (4 minutes, 33 seconds total), the reentry was entirely nominal. Splashdown occurred at 18:07:41 UTC near American Samoa in the Pacific Ocean. The USS Iwo Jima quickly recovered spacecraft and crew.

The post-flight mishap investigation revealed that Oxygen Tank No. 2, located deep within the bowels of the SM, exploded when the crew conducted a cryo stir of its multi-phase contents. Unknown to all was the fact that a mismatch between the tank heater and thermostat had resulted in the Teflon insulation of the internal wiring being severely damaged during previous ground operations. This meant that the tank was now a bomb and would detonate its contents when used the next time. In this case, the next time was in flight. The warning signs were there, but went unheeded.

Apollo 13 never landed at Fra Mauro. And none of its crew would ever again fly in space. But in many ways, Apollo 13 was NASA’s finest hour. Overcoming myriad seemingly intractable obstacles in the aftermath of a completely unanticipated catastrophe, deep in trans-lunar space, will forever rank high among the legendary accomplishments of spaceflight. With essentially no margin for error and in the harsh glare of public scrutiny, NASA wrested victory from the tentacles of almost certain failure and brought three weary men safely back to their home planet.