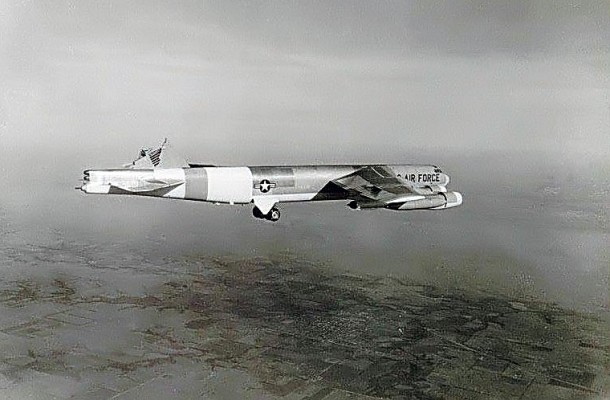

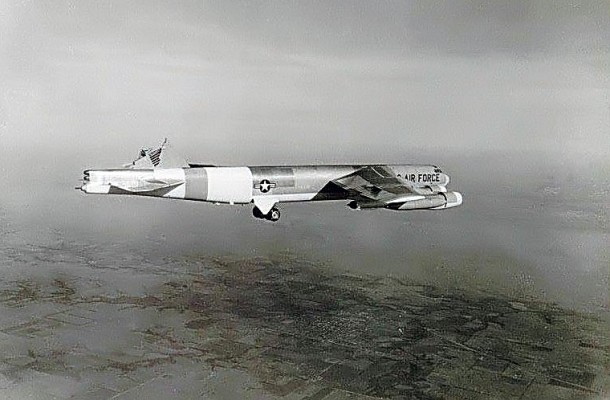

Fifty-six years ago this week, a USAF/Boeing B-52H Stratofortress landed safely following structural failure of its vertical tail during an encounter with unusually severe clear air turbulence. The harrowing incident occurred as the aircraft was undergoing structural flight testing in the skies over East Spanish Peak, Colorado.

Turbulence is the unsteady, erratic motion of an atmospheric air mass. It is attributable to factors such as weather fronts, jet streams, thunder storms and mountain waves. Turbulence influences the motion of aircraft that are subjected to it. These effects range from slight, annoying disturbances to violent, uncontrollable motions which can structurally damage an aircraft.

Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) occurs in the absence of clouds. Its presence cannot be visually observed and is detectable only through the use of special sensing equipment. Hence, an aircraft can encounter CAT without warning. Interestingly, the majority of in-flight injuries to aircraft crew and passengers are due to CAT.

On Friday, 10 January 1964, USAF B-52H (S/N 61-023) took-off from Wichita, Kansas on a structural flight test mission. The all-Boeing air crew consisted of instructor pilot Charles Fisher, pilot Richard Curry, co-pilot Leo Coors, and navigator James Pittman. The aircraft was equipped with 3-axis accelerometers and other sensors to record in-flight loads and stresses.

An 8-hour flight was scheduled on a route that from Wichita southwest to the Rocky Mountains and back. The mission called for 10-minutes runs of 280, 350 and 400 KCAS at 500-feet AGL using the low-level mode of the autopilot. The initial portion of the mission was nominal with only light turbulence encountered.

However, as the aircraft turned north near Wagon Mound, New Mexico and headed along a course parallel to the mountains, increasing turbulence and tail loads were encountered. The B-52H crew then elected to discontinue the low level portion of the flight. The aircraft was subsequently climbed to 14,300 feet AMSL preparatory to a run at 350 KCAS.

At approximately 345 KCAS, the Stratofortress and its crew experienced an extreme turbulence event that lasted roughly 9 seconds. In rapid sequence the aircraft pitched-up, yawed to the left, yawed back to the right and then rolled right. The flight crew desperately fought for control of their mighty behemoth. But the situation looked grim. The order was given to prepare to bailout.

Finally, the big bomber’s motion was arrested using 80% left wheel authority. However, rudder pedal displacement gave no response. Control inputs to the elevator produced very poor response as well. Directional stability was also greatly reduced. Nevertheless, the crew somehow kept the Stratofortress flying nose-first.

The B-52H crew informed Boeing Wichita of their plight. A team of Boeing engineering experts was quickly assembled to deal with the emergency. Meanwhile, a Boeing-bailed F-100C formed-up with the Stratofortress and announced to the crew that most of the aircraft’s vertical tail was missing! The stricken aircraft’s rear landing was then deployed to add back some directional stability.

With Boeing engineers on the ground working with the B-52H flight crew, additional measures were taken in an effort to get the Stratofortress safely back on the ground. These measures included a reduction in airspeed, controlling aircraft center-of-gravity via fuel transfer, judicious use of differential thrust, and selected application of speed brakes.

Due to high surface winds at Wichita, the B-52H was vectored to Eaker AFB in Blytheville, Arkansas. A USAF/Boeing KC-135 was dispatched to escort the still-flying B-52H to Eaker and to serve as an airborne control center as both aircraft proceeded to the base. Amazingly, after flying 6 hours sans a vertical tail, the Stratofortress and her crew landed safely.

Safe recovery of crew and aircraft brought additional benefits. There were lots of structural flight test data! It was found that at least one gust in the severe CAT encounter registered at nearly 100 mph. Not only were B-52 structural requirements revised as a result of this incident, but those of other existing and succeeding aircraft as well.

B-52H (61-023) was repaired and returned to the USAF inventory. It served long and well after its close brush with catastrophe in January 1964. The aircraft spent the latter part of its flying career as a member of the 2nd Bomb Wing at Barksdale AFB, Louisiana. The venerable bird was retired from active service in July of 2008.

Seventy-one years ago this month, the USAF/Bell XS-1 became the first aircraft of any type to achieve supersonic flight during a climb from a ground take-off. The daring feat took place at Muroc Air Force Base with famed USAF Captain Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager at the controls of the rocket-powered XS-1.

Rocket-powered X-aircraft such as the XS-1, X-1A, X-2 and X-15 were air-launched from a larger carrier aircraft. With the test aircraft as its payload, this “mother ship” would take-off and climb to drop altitude using its own fuel load. This capability permitted the experimental aircraft to dedicate its entire propellant load to the flight research mission proper.

The USAF/Bell XS-1 was the first X-aircraft. It was carried to altitude by a USAF/Boeing B-29 mother ship. XS-1 air-launch typically occurred at 220 mph and 22,000 feet. On Tuesday, 14 October 1947, the XS-1 first achieved supersonic flight. The XS-1 would ultimately fly as fast as Mach 1.45 and as high as 71,902 feet.

All but two (2) of the early X-aircraft were Air Force developments. The exceptions were products of the United States Navy flight research effort; the USN/Douglas D-558-I Sky Streak and USN/Douglas D-558-II Sky Rocket. The Sky Streak was a turbojet-powered, straight-winged, transonic aircraft. The Sky Rocket was supersonic-capable, swept-winged, and rocket-powered. Each aircraft was originally designed to be ground-launched.

In the best tradition of inter-service rivalry, the Navy claimed that the D-558-I at the time was the only true supersonic airplane since it took to the air under its own power. Interestingly, the Sky Streak was able fly beyond Mach 1 only in a steep dive. Nonetheless, the Air Force was indignant at the Navy’s thinly-disguised insinuation that the XS-1 was somehow less of an X-aircraft because it was air-launched.

Motivated by the Navy’s affront to Air Force honor, the junior military service devised a scheme to ground-launch the XS-1 from Rogers Dry Lake at Muroc (now Edwards) Air Force Base. The aircraft would go supersonic in what was essentially a high performance take-off and climb. To boot, the feat was timed to occur just before the Navy was to fly its rocket-powered D-558-II Sky Rocket. Justice would indeed be righteously served!

XS-1 Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-062) was selected for the ground take-off mission. Captain Charles E. Yeager would pilot the sleek craft with Captain Jackie L. Ridley providing vital engineering support. Due to its somewhat fragile landing gear, the XS-1 propellant load was restricted to 50% of capacity. This provided approximately 100 seconds of rocket-powered flight.

On Wednesday, 05 January 1949, Yeager fired all four (4) barrels of his XLR-11 rocket motor. Behind 6,000 pounds of thrust, the XS-1 rapidly accelerated along the smooth surface of the dry lake. After a take-off roll of only 1,500 feet and with the XS-1 at 200 mph, Yeager pulled back on the control yoke. The XS-1 virtually leapt into the desert air.

The aerodynamic loads were so high during gear retraction that the actuator rod broke and the wing flaps tore away. Unfazed, Yeager’s eager steed continued to climb rapidly. Eighty seconds after brake release, the XS-1 hit Mach 1.03 passing through 23,000 feet. Yeager then brought the XS-1 to a wings level flight attitude and shutdown his XLR-11 power plant.

Following a brief glide back to the dry lake, Yeager executed a smooth dead-stick landing. Total flight time from lift-off to touchdown was on the order of 150 seconds. While a little worst for wear, the plucky XS-1 had performed like a champ and successfully accomplished something that it was really not designed to do.

Yeager was so excited during the take-off roll and high performance climb that he forgot to put his oxygen mask on! Potentially, that was a problem since the XS-1 cockpit was inerted with nitrogen. Fortunately, late in the climb, Yeager got his mask in place just before he went night-night for good.

Suffice it to say that the United States Navy was not particularly fond of the display of bravado and airmanship exhibited on that long-ago January day. The Air Force had emerged victorious in a classic contest of one-upmanship. At a deeper level, Air Force honor had been upheld. And, as was often the case in the formative years of the United States Air Force, it was a test pilot named Chuck Yeager who brought victory home to the blue suiters.

Forty-seven years ago this month, NASA successfully conducted the sixth lunar landing mission of the Apollo Program. Known as Apollo 17, the flight marked the last time that men from the planet Earth explored the surface of the Moon.

Apollo 17 was launched from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Thursday, 07 December 1972. With a lift-off time of 05:33:00 UTC, Apollo 17 was the only night launch of the Apollo Program. Those who witnessed the event say that night turned into day as the incandescent exhaust plumes of the Saturn V’s quintet of F-1 engines lit up the sky around the Cape.

The target for Apollo 17 was the Taurus-Littrow valley in the lunar highlands. Located on the southeastern edge of Mare Serenitatis, the landing site was of particular interest to lunar scientists because of the unique geologic features and volcanic materials resident within the valley. Planned stay time on the lunar surface was three days.

The Apollo 17 crew consisted of Commander Eugene A. Cernan, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Ronald E. Evans and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Harrison H. Schmitt. While this was Cernan’s third space mission, both Evans and Schmitt were space rookies. Astronaut Schmitt was a professional geologist and the only true scientist to explore the surface of the Moon.

With Evans circling the Moon solo in the Command Module America, Cernan and Schmitt successfully landed their Lunar Module Challenger at 19:54:57 UTC on Monday, 11 December 1972. Their lunar stay lasted more than three days. The astronauts used the Lunar Rover for transport over the lunar surface as they conducted a trio of exploratory excursions that totaled more than 22 hours.

Cernan and Schmitt collected nearly 244 pounds of lunar geologic materials while exploring Taurus-Littrow. As on previous missions, the Apollo 17 crew deployed a sophisticated set of scientific instruments used to investigate the lunar surface environment. Indeed, the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) deployed during during lunar landing missions measured and transmitted vital lunar environmental data back to Earth through September 1977 when the data acquisition effort was officially terminated.

The Apollo 17 landing party departed the Moon at 22:54:37 UTC on Thursday, 14 December 1972. In a little over two hours, Challenger and America were docked. Following crew and cargo transfer to America, Challenger was later intentionally deorbited and impacted the lunar surface. The Apollo 17 crew then remained in lunar orbit for almost two more days to make additional measurements of the lunar environment.

At 23:35:09 UTC on Saturday, 16 December 1972, Apollo 17 blasted out of lunar orbit and headed home. Later, CMP Ron Evans performed a trans-Earth spacewalk to retrieve film from Apollo 17 ’s SIM Bay camera. Evans’ brave spacewalk occurred on Sunday, 17 December 1972 (69th anniversary of the Wright Brothers first powered flight) and lasted 65 minutes and 44 seconds.

Apollo 17 splashdown occurred near America Samoa in the Pacific Ocean at 19:24:59 UTC on Tuesday, 19 December 1972. America and her crew were subsequently recovered by the USS Ticonderoga.

Apollo 17 set a number of spaceflight records including: longest manned lunar landing flight (301 hours, 51 minutes, 59 seconds); longest lunar stay time (74 hours, 59 minutes, 40 seconds); total lunar surface extravehicular activity time (22 hours, 3 minutes, 57 seconds); largest lunar sample return (243.7 pounds), and longest time in lunar orbit (147 hours, 43 minutes, 37 seconds).

Apollo 17 successfully concluded America’s Apollo Lunar Landing Program. Of a sudden it seemed, America’s — and the world’s — greatest adventure was over. However, the anticipation was that the United States would return in the not-too-distant future. Indeed, Gene Cernan, the last man to walk on the Moon, spoke the following words from the surface:

“As I take man’s last step from the surface, back home for some time to come — but we believe not too long into the future — I’d like to just [say] what I believe history will record — that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.”

It has now been 47 years since the Commander of Apollo 17 spoke those stirring words from the valley of Taurus-Littrow. Gene Cernan passed away in January of 2017. He and most space experts of his day figured we would surely have returned to the Moon by now. Certainly in the 20th century. Yet, there has been no return. Thus, the historical record continues to list the name of Eugene A. Cernan as the last man to walk on the surface of the Moon.

One-hundred and sixteen years ago today, the Wright Flyer became the first aircraft in history to achieve powered flight. The site of this historic event was Kill Devil Hills located near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Americans Wilbur and Orville Wright began their legendary aeronautical careers in 1899. In a matter of just four short years, the brothers would go from complete aeronautical novices to inventors and pilots of the world’s first successful powered aircraft. Neither man attended college nor received even a high school diploma.

The Wright Flyer measured roughly 21 feet in length and had a wing span of approximately 40 feet. The biplane aircraft had an empty weight of 605 lbs. Power was provided by a single 12 horsepower, 4-cylinder engine that drove twin 8.5 foot, two-blade propellers.

The Flyer made a powered take-off run along a 60-foot wooden guide rail. The aircraft was mounted on a two-wheel dolly that rode along the track and was jettisoned at lift-off. The Flyer pilot lay prone in the middle of the lower wing. Twin elevator and rudder surfaces provided pitch and yaw control, respectively. Roll control was via differential wing warping.

The Wright Brothers had come close to achieving a successful powered flight with the Wright Flyer on Monday, 14 December 1903. Wilbur, who had won the coin toss, was the pilot for the initial attempt. However, the Flyer stalled and hit the ground sharply just after take-off. Wilbur was unhurt, but repair of the damaged aircraft would take two days.

The next attempt flight took place on Thursday, 17 December 1903. The weather was terrible. Windy and rainy. Even after the rain abated, the wind continued to blow in excess of 20 mph. The Wrights decided to fly anyway. It was now Orville’s turn as command pilot.

Orville took his position on the Flyer and was quickly launched into the wind. Once airborne, the aircraft proved difficult to control as it porpoised up and down along the flight path. Nonetheless, Orville kept the Flyer in the air for 12 seconds before landing 120 feet from the take-off point. Other than a damaged skid, the aircraft was intact and the pilot unhurt. Powered flight was a reality!

Three more flights followed on that momentous occasion as the two brothers alternated piloting assignments. The fourth flight was the longest in both time aloft and distance flown. With Wilbur at the controls, the Wright Flyer flew for 59 seconds and landed 852 feet from the take-off point.

The Wright Brothers father, Milton, would soon learn of the epic events that December day in North Carolina. Orville’s verbatim Western Union telegram message sent to Dayton, Ohio read:

Success four flights thursday morning all against twenty one mile wind started from level with engine power alone average speed through air thirty one miles longest 57 [sic] seconds inform press home Christmas.

Fifty-six years ago to the day, USAF NF-104A (S/N 56-762; Ship 3) crashed to destruction following a rocket-powered zoom to 101,600 feet above mean sea level (AMSL). The pilot, USAF Colonel Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager, was seriously injured, but survived when he successfully ejected from the stricken aircraft approximately 5,000 feet above ground level (AGL).

The USAF/Lockheed NF-104A was designed to provide spaceflight-like training experience for test pilots attending the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS) at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The type was a modification of the basic F-104A Starfighter aircraft. Three copies of the NF-104A were produced (S/N’s 56-0756, 56-0760 and 56-0762). It was the ultimate zoom flight platform.

In addition to a stock General Electric J79-GE-3 turbojet, the NF-104A was powered by a Rocketdyne LR121-NA-1 rocket motor. The J79 generated 15,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner and burned JP-4. The LR-121 produced 6,000 pounds of thrust and burned a combination of JP-4 and 90% hydrogen peroxide. Rocket motor burn time was on the order of 90 seconds.

Around 1400 hours PST on Tuesday, 10 December 1963, Colonel Yeager took-off from Edwards Air Force Base to attempt his second zoom flight of the day. That morning, he had zoomed NF-104A, S/N 56-760 to an altitude of 108,700 feet. Four days earlier, Yeager had zoomed the same airplane to the highest altitude he would ever achieve in the type; 110,500 feet AMSL.

The zoom apex altitude for the ill-fated afternoon flight was only 101,600 feet AMSL with rocket motor burnout taking place 5 seconds post-apogee. That is, the aircraft was already on the descending leg of the zoom trajectory and in the early stages of reentry. Yeager later reported that the aircraft angle-of-attack at that point was on the order of 50 deg; a figure that is well past the NF-104A pitch-up angle-of-attack (i.e., 14-17 deg). Yeager had flown the aircraft this way on previous zoom flights and had always been able to lower the nose via reaction control system (RCS) inputs.

Unfortunately, the RCS did not not have sufficient pitch control authority to bring the nose down on the mishap flight. As a result, the aircraft began the reentry in an extremely nose-high attitude. As the dynamic pressure rapidly built-up, the NF-104A departed controlled flight and went through a series of post-stall gyrations between 90,000 and 65,000 feet. These gyrations ultimately led to a series of flat spins occurring between 65,000 and 20,000 feet.

Running out of altitude, Yeager desperately deployed his drag parachute as an anti-spin device. This action indeed stopped the flat spin. Airspeed picked-up to 180 KIAS with the aircraft hanging in the chute, but the pilot was unable to get an air-start on his J79 turbojet which had spooled down to 6% of maximum RPM. At 12,000 feet, Yeager jettisoned his drag chute and the NF-104A immediately pitched-up again into a flat spin. After three-quarters of a turn, Yeager ejected about 5,000 feet AGL. Yeager landed close to where the mishap aircraft had impacted and was in a great deal of pain due to burns he received during the ejection process. Happily, he survived this traumatic event and recovered completely from his injuries.

Objective analysis of the loss of NF-104A, S/N 56-762 reveals that the aircraft simply was not flown in a manner commensurate with the intricacies of the zoom environment. The critical importance of quickly intercepting and maintaining the target inertial pitch angle during pull-up had been repeatedly demonstrated by other test pilots as had proper control of aircraft angle-of-attack during reentry. Colonel Yeager elected not to fly the aircraft in accordance with these dictates.

In all of his NF-104A zoom attempts, Colonel Yeager consistently flew the airplane over the top at angles-of-attack well beyond the pitch-up value. RCS control authority was sufficient to lower the nose to sub-pitch-up angles-of-attack just prior to reentry on all but the mishap flight. Unfortunately, the low apex altitude (101,600 feet AMSL) of that zoom resulted in a higher dynamic pressure that, in conjunction with very high angles-of-attack, produced a nose-up aerodynamic pitching moment that the RCS could not overcome.

The aircraft mishap of 10 December 1963 forever changed the way in which NF-104A pilots would be allowed to fly the rocket-powered zoom mission. Prior to the mishap, the NF-104A had been zoomed to an altitude of 120,800 feet AMSL by USAF Major Robert W. Smith on 06 December 1963. This unofficial United States record still stands today. After a mishap investigation, NF-104A maximum altitude was limited to 108,000 feet AMSL. This restricted performance was mandated ostensibly out of concern for the safety of ARPS student test pilots.

The ultimate and lasting result of the post-mishap restriction on NF-104A flight performance was that it did a great disservice to ARPS student test pilots in that it made their spaceflight training experience something less than what it could and should have been. It is ironic that, although the correct manner in which to zoom the airplane had been repeatedly validated by USAF and Lockheed test pilots prior to the 56-0762 mishap, the decision to restrict NF-104A performance was based on a single flight which clearly demonstrated how not to fly the airplane.

Fifty-six years ago to the day, USAF Major Robert W. Smith zoomed the rocket-powered USAF/Lockheed NF-104A to an unofficial world record altitude of 120,800 feet. This mark still stands as the highest altitude ever achieved by a United States aircraft from a runway take-off.

A zoom maneuver is one in which aircraft kinetic energy (speed) is traded for potential energy (altitude). In doing so, an aircraft can soar well beyond its maximum steady, level altitude (service ceiling). The zoom maneuver has both military and civilian flight operations value.

The USAF/Lockheed NF-104A was designed to provide spaceflight-like training experience for test pilots attending the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS) at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The type was a modification of the basic F-104A Starfighter aircraft. Three copies of the NF-104A were produced (S/N’s 56-0756, 56-0760 and 56-0762). It was the ultimate zoom flight platform.

In addition to a stock General Electric J79-GE-3 turbojet, the NF-104A was powered by a Rocketdyne LR121-NA-1 rocket motor. The J79 generated 15,000 pounds of thrust in afterburner and burned JP-4. The LR-121 produced 6,000 pounds of thrust and burned a combination of JP-4 and 90% hydrogen peroxide. Rocket motor burn time was on the order of 90 seconds.

The NF-104A was kinematically capable of zooming to altitudes approaching 125,000 feet. As such, it was a combined aircraft, rocket, and spacecraft. The pilot had to blend aerodynamic and reaction controls in the low dynamic pressure environment near the zoom apex. He was also required to fly in a full pressure suit for survival at altitudes beyond the Armstrong Line.

On Friday, 06 December 1963, Bob Smith took-off from Edwards and headed west for the Pacific Ocean. Out over the sea, he changed heading by 180 degrees in preparation for the zoom run-in. At a point roughly 100 miles out, Smith then accelerated the NF-104A (S/N 56-0760) along a line that would take him just north of the base. Arriving at Mach 2.4 and 37,000 feet, Smith then initiated a 3.75-g pull to a 70-degree aircraft pitch angle. Turbojet and rocket were at full throttle.

Things happened very quickly at this point. Smith brought the J79 turbojet out of afterburner at 65,000 feet and then moved the throttle to the idle detent at 80,000 feet. The rocket motor burned-out around 90,000 feet. Smith controlled the aircraft (now spacecraft) over the top of the zoom using 3-axis reaction controls. The NF-104A’s arcing parabolic trajectory subjected him to 73 seconds of weightlessness. Peak altitude achieved was 120,800 feet above mean sea level.

On the back side of the zoom profile, Bob Smith restarted the windmilling J79 turbojet and set-up for landing at Edwards. He touched down on the main runway and rolled out uneventfully. Total mission time from brake-release to wheels-stop was approximately 25 minutes.

Much more could be said about the NF-104A and its unique mission. Suffice it to say here that two of the aircraft ultimately went on to serve in the ARPS from 1968 to 1971. The only remaining aircraft today is 56-0760 which sits on a pole in front of the USAF Test Pilot School (TPS) at Edwards.

Bob Smith went on to make many other noteworthy contributions to aviation and his nation. Having flown the F-86 Sabre in Korea, he volunteered to fly combat in Viet Nam in his 40th year. Stationed at Korat AFB in Thailand, he commanded the 34th Fighter Squadron of the 388th Tactical Fighter Wing. Smith flew 100 combat missions in the fabled F-105D Thunderchief; many of which involved the infamous Pack VI route in North Viet Nam.

Bob Smith was a true American hero. Like so many of the airmen of his day, Smith was a man whose dedication, service, and courage went largely unnoticed and underappreciated by his fellow countrymen. Bob Smith’s final flight came just 3 months shy of his 82nd birthday on Thursday, 19 August 2010.

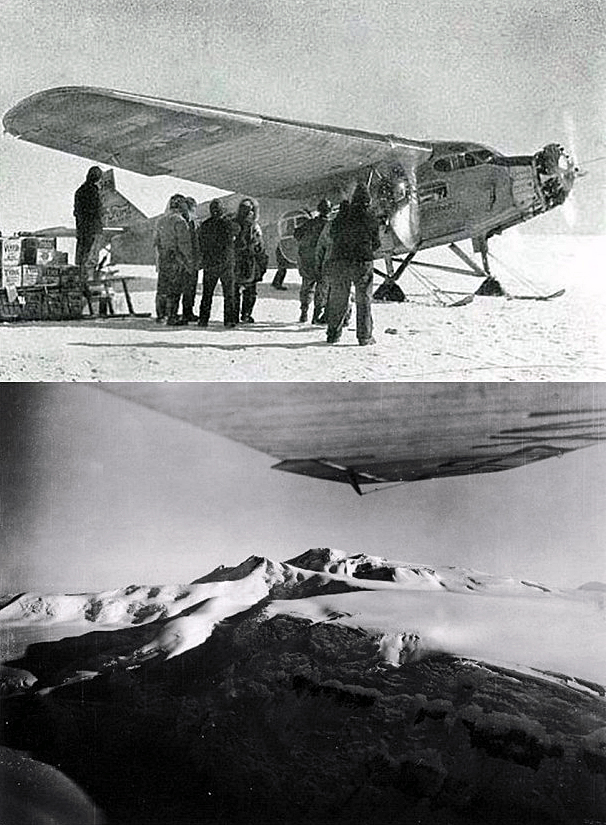

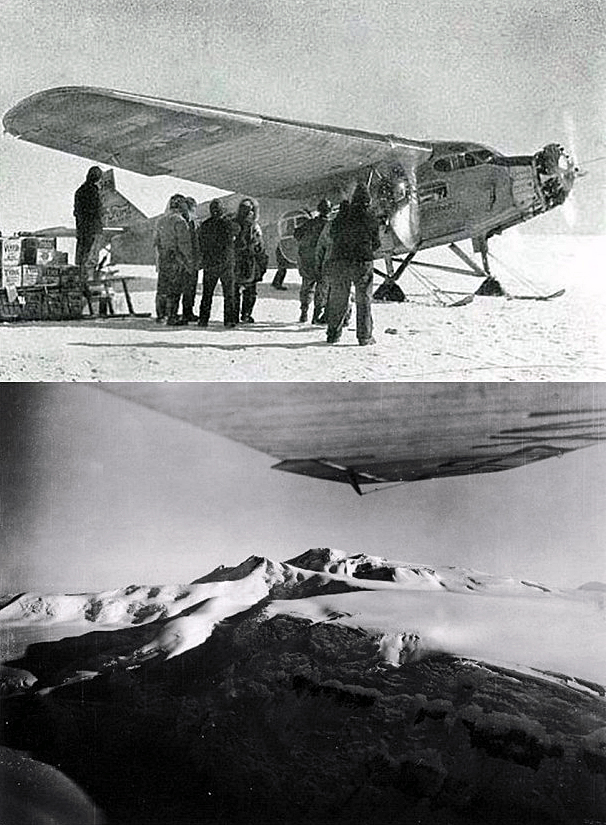

Ninety years ago to the day, a four-man crew became the first Antarctic explorers to fly over the Earth’s South Pole. The aircraft used to make the historic flight was a Ford Trimotor.

While substantial exploration of the Arctic and Antarctic by land and sea had occurred far earlier, exploration of these regions by air was in its infancy during the decade of the 1920′s. Of particular focus was the goal to fly over both the North and South Poles.

The historic first flight to the South Pole originated from Little America, an exploration base camp situated on Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf. Distance to the South Pole was about 800 miles as the crow flies.

A Ford Trimotor aircraft, the Floyd Bennett (S/N NX4542), was selected for the epic polar air journey. The crew consisted of pilot Bernt Balchen, co-pilot Harold June, navigator Richard E. Byrd, and radio operator Ashley McKinley.

The fabled Trimotor was well-suited for the rigors of polar flight. The all-metal aircraft measured 50-feet in length and had a wing span of 76-feet. Empty weight was roughly 6,500 pounds. Power was provided by a single 520-HP Wright Cylone and a pair of 200-HP Wright Whirlwind radial engines.

Following departure from Little America at 02:39 UTC, the Floyd Bennett headed for the South Pole. Navigation was via sun compass due to the proximity of the South Magnetic Pole.

Myriad glaciers, massifs, plateaus, and crevasses marked the stark, rugged landscape unfolding under the Floyd Bennett’s flight path. The most imposing of these geological features were the Queen Maud Mountains that towered more than 11,000 feet above sea level.

Pilot Balchen struggled to get his aircraft over the high mountain pass that runs between Mounts Fridtjof and Fisher. The crew jettisoned empty fuel cans and hundreds of pounds of precious food to lighten the load. The Floyd Bennett cleared the terrain by about 600 feet.

Just after 1200 UTC (local midnight) on Friday, 29 November 1929, the Floyd Bennett and her crew flew over the Earth’s South Pole. After briefly loitering around the Pole, the aircraft headed back to Little America at 1225 UTC.

According to plan, Balchen landed the airplane to take on 200 gallons of fuel that had been pre-positioned at the base of the Liv Glacier. The Floyd Bennett took-off again and landed back at Little America around 21:10 UTC. Total mission time was nearly 19 hours.

United States Navy Commander Richard E. Byrd now had flown over both poles. He would go on to successfully explore the Antarctic for many more years. For his part in the South Pole overflight, Byrd was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral.

Today, the aircraft that made the first flight over the South Pole in November 1929 is displayed in the Heroes of the Sky exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Fifty-two years ago this month, the No. 3 USAF/North American X-15 research aircraft broke-up during a steep dive from an apogee of 266,000 feet. The pilot, USAF Major Michael J. Adams, perished when his aircraft was ripped apart by aerodynamic forces as it passed through 65,000 feet at more than 2,500 mph.

The hypersonic X-15 was arguably the most productive X-Plane of all time. Between 1959 and 1968, a trio of X-15 aircraft were flown by a dozen pilots for a total of 199 official flight research missions. Along the way, the fabled X-15 established manned aircraft records for speed (4,534 mph; Mach 6.72) and altitude (354,200 feet).

The X-15 was a rocket, aircraft and spacecraft all rolled into one. Burning anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen, its XLR-99 rocket engine generated 57,000 lbs of sea level thrust. Reaction controls were required for flight in vacuum. Each flight also required careful management of aircraft energy state to ensure a successful, one attempt only, unpowered landing.

On Wednesday, 15 November 1967, the No. 3 X-15 (S/N 56-6672) made the 191st flight of the X-15 Program. In the cockpit was USAF Major Michael J. Adams making his 7th flight in the X-15. He had been flying the aircraft since October of 1966. Like all X-15 pilots, he was a skilled, accomplished test pilot used to dealing with the demands and high risk of flight research work.

X-15 Ship No. 3 was launched from its B-52B (S/N 52-0008) mothership over Nevada’s Delamar Dry Lake at 18:30 UTC. As the X-15 fell away from the launch aircraft at Mach 0.82 and 45,000 feet, Adams fired the XLR-99 and started uphill along a trajectory that was supposed to top-out around 250,000 feet. If all went well, Adams would land on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base in California roughly 10 minutes later.

Around 85,000 on the way upstairs, Adams became distracted when an electrical disturbance from an onboard flight experiment adversely affected the X-15’s flight control system, flight computer and inertial reference system. As a result, data on several key cockpit displays became corrupted. Though with some difficulty, Adams pressed-on with the flight which peaked-out around 266,000 feet approximately three (3) minutes from launch.

As a result of degraded flight systems and perhaps disoriented by vertigo, Mike Adams soon discovered that his aircraft was veering from the intended heading. He indicated to the control room at Edwards that his steed was not controlling correctly. Passing through 230,000 feet, Adams cryptically radioed that he was in a Mach 5 spin. Mission control was stunned. There was nothing in the X-15 flight manual that even addressed such a possibility.

Incredibly, Mike Adams somehow managed to recover from his hypersonic spin as the X-15 passed through 118,000 feet. However, the aircraft was inverted and in a 45-degree dive at Mach 4.7. Still, Adams may very well have recovered from this precarious flight state but for the appearance of another flight system problem just as he recovered the X-15 from its horrific spin.

X-15 Ship No. 3 was configured with a Minneapolis-Honeywell adaptive flight control system (AFCS). Known as the MH-96, the AFCS was supposed to help the pilot control the X-15 during high performance flight. Unfortunately, the unit entered a limit-cycle oscillation just after spin recovery and failed to change gains as the dynamic pressure rapidly increased during Ship No. 3’s final descent. This anomaly saturated the X-15 flight control system and effectively overrode manual inputs from the pilot.

The limit-cycle oscillation drove the X-15’s pitch rate to intolerably-high values in the face of rapidly increasing dynamic pressure. Passing through 65,000 feet at better than 2,500 mph (Mach 3.9), Ship No. 3 came apart northeast of Johannesburg, California. The main wreckage impacted just northwest of Cuddeback Dry Lake. Mike Adams had made his final flight.

For his flight to 266,000 feet, USAF Major Michael J. Adams was posthumously awarded Astronaut Wings by the United States Air Force. His name was included on the roll of the Astronaut Memorial at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in 1991. Finally, on Saturday, 08 May 2004, a small memorial was erected to the memory of Major Adams near his X-15 crash site situated roughly 39 miles northeast of Edwards Air Force Base.

Fifteen years ago to the day, the NASA X-43A scramjet-powered flight research vehicle reached a record speed of over 6,600 mph (Mach 9.68). In doing so, the X-43A eclipsed its own record speed of Mach 6.83 (4,600 mph) and became the fastest air breathing aircraft of all time.

In 1996, NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X. The central goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed close to 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The third and final flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Tuesday, 16 November 2004. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 21:08 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 22:34:43 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership. Following a 5 second free fall, rocket motor ignition occurred and the HXLV initiated a pull-up to start its climb and acceleration to the test window. It took the HXLV 75 seconds to reach a speed of slightly over Mach 10.

Following rocket motor burnout and a brief coast period, the HXRV (X-43A) successfully separated from the Pegasus booster at 109,440 feet and Mach 9.74. The HXRV scramjet was operative by Mach 9.68. Supersonic combustion and thrust production were successfully achieved. Total engine-on duration was approximately 11 seconds.

As the X-43A decelerated along its post-burn descent flight path, the aircraft performed a series of data gathering flight maneuvers. A vast quantity of high-quality aerodynamic and flight control system data were acquired for Mach numbers ranging from hypersonic to transonic. Finally, the X-43A impacted the Pacific Ocean at a point about 850 nautical miles due west of its launch location. Total flight time was approximately 15 minutes.

The HYPER-X Program was now history. Supersonic combustion and thrust production of an airframe-integrated scramjet had indeed been achieved for the first time in flight; a goal that dated back to before the X-15 Program. Along the way, the X-43A established a speed record for air breathing aircraft and earned several Guinness World Records for its efforts.

As a footnote to the X-43A story, the HYPER-X Flight 3 mission would also be the last for NASA’s fabled B-52B mothership. The aircraft that launched many of the historic X-15, M2-F2, M2-F3, X- 24A, X-24B and HL-10 flight research missions, and all three HYPER-X flights, would take to the air no more. In tribute, B-52B (S/N 52-0008) now occupies a place of honor at a point near the North Gate of Edwards Air Force Base.

Fifty-one years ago this month, NASA successfully conducted the first manned Apollo Earth-orbital mission with the flight of Apollo 7 (Mission AS-205). This mission was a critically-important milestone along the path to the first manned lunar landing in July 1969.

The launch of Apollo 7 took place from Launch Complex 34 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida at 15:02:45 UTC on Friday, 11 October 1968. The flight crew consisted of NASA astronauts Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham. Their primary goal was to thoroughly qualify the new Apollo Block II Command Module (CM) during 11 days in space.

Apollo 7 was not only the first flight of the Block II CM, but in fact the first manned mission in the Apollo Program. Apollo 7 also featured the first use of the Saturn IB launch vehicle in a manned mission. Apollo 7’s critical nature stemmed from the tragic Apollo 1 fire that took the lives of Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom, Edward H. White II, and Roger B. Chaffee on Friday, 27 January 1967.

The Apollo 1 fire was attributed to numerous deficiencies in the design, construction, and testing of its Block I CM. The Block II spacecraft flown on Apollo 7 was a major redesign of the Apollo Command Module and was in every sense superior to the Block I vehicle. However, it had taken 21 months to return to flight status and the Nation’s goal of a manned lunar landing within the decade of the 1960’s was in serious jeopardy.

The Apollo 7 crew orbited the Earth 163 times at an orbital altitude that varied between 125 and 160 nautical miles. In that time, they rigorously tested every aspect of their Block II CM. This testing included 8 firings of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) while in orbit. Apollo 7 splashdown occurred in the Atlantic Ocean near the Bermuda Islands at 11:11:48 UTC on Tuesday, 22 October 1968.

The Nation’s Lunar Landing Program overwhelmingly got the unqualified success that it desperately needed from the Apollo 7 mission. The Apollo Block II CM would provide yeoman service throughout the time of Apollo. The spacecraft would also go on to see service in the Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project programs.

While the technical performance of the Apollo 7 crew was unquestionably superb, their interaction with Mission Control at Johnson Spacecraft Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas was quite strained. The crew suffered from head colds through much of the mission and the food quality was poor. Coupled with Houston’s incessant attempts to cramp more tasks into each moment of the mission, Apollo 7 Commander Schirra took control of his ship and made the ultimate decisions as to what work would be performed onboard the spacecraft.

The flight of Apollo 7 would be Wally Schirra’s last mission in space as he had announced prior to flight. Schirra holds the distinction of being the only astronaut to have flown Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions.

Interestingly, Apollo 7 was not only Schirra’s last time in space, but it was Donn Eisele’s and Walt Cunningham’s first and last space mission as well. That there is a direct connection between this historical fact and the crew’s insubordinate behavior during Apollo 7 is obvious to the inquiring mind.