Fifty-one years ago this month, NASA astronauts Leroy Gordon “Gordo” Cooper and Charles M. “Pete” Conrad set a new spaceflight endurance record during the flight of Gemini 5. It was the third of ten (10) missions in the historic Gemini spaceflight series. The motto for the mission was “Eight Days or Bust”.

The purpose of Project Gemini was to develop and flight-prove a myriad of technologies required to get to the Moon. Those technologies included spacecraft power systems, rendezvous and docking, orbital maneuvering, long duration spaceflight and extravehicular activity.

The Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the deboost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbit attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

Gemini-Titan V (GT-5) lifted-off at 13:59:59 UTC from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, 21 August 1965. The two-stage Titan II launch vehicle placed Gemini 5 into a 189 nautical mile x 87 nautical mile elliptical orbit.

A primary purpose of the Gemini 5 mission was to stay in orbit at least eight (8) days. This was the minimum time it would take to fly to the Moon, land and return to the Earth. Other goals of the Gemini 5 mission were to test the first fuel cells, deploy and rendezvous with a special rendezvous pod and conduct a variety of medical experiments.

Despite fuel cell problems, electrical system anomalies, reaction control system issues and the cancellation of various experiments, Gemini 5 was able to meet the goal of an 8-day flight. But it wasn’t easy. The last days of the mission were especially demanding since the crew didn’t have much to do. Pete Conrad called his Gemini 5 experience “8 days in a garbage can.”

On Sunday, 29 August 1965, Gemini 5 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 12:55:13 UTC. Mission elapsed time was 7 days, 22 hours, 55 minutes and 13 seconds. A new spaceflight endurance record.

Gemini 5 was Gordon Cooper’s last spaceflight. Cooper left NASA due to a deteriorating relationship with management. Pete Conrad flew three (3) more times in space. In particular, he commanded the Gemini 11, Apollo 12 and Skylab I missions. Indeed, Conrad’s Apollo 12 experience made him the third man to walk on surface of the Moon.

Fifty-three years ago today, NASA chief research pilot Joseph A. Walker flew X-15 Ship No. 3 (S/N 56-6672) to an altitude of 354,200 feet. This flight would mark the highest altitude ever achieved by the famed hypersonic research vehicle.

Carried aloft by NASA’s NB-52A (S/N 52-0003) mothership, Walker’s X-15 was launched over Smith Ranch Dry Lake, Nevada at 17:05:42 UTC. Following drop at around 45,000 feet and Mach 0.82, Walker ignited the X-15’s small, but mighty XLR-99 rocket engine and pulled into a steep vertical climb.

The XLR-99 was run at 100 percent power for 85.8 seconds with burnout occurring around 176,000 feet on the way uphill. Maximum velocity achieved was 3,794 miles per hour which tranlates to Mach 5.58 at the burnout altitude. Following burnout, Walker’s X-15 gained an additional 178,200 feet in altitude as it coasted to apogee.

Joe Walker went over the top at 354,200 feet (67 miles). Although he didn’t have much time for sight-seeing, the Earth’s curvature was strikingly obvious to the pilot as he started downhill from his lofty perch. Walker subsequently endured a hefty 5-g’s of eyeballs-in normal acceleration during the backside dive pull-out. The aircraft was brought to a wings-level attitude at 70,000 feet. Shortly after, Walker greased the landing on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The X-15 maximum altitude flight lasted 11 minutes and 8 seconds from drop to nose wheel stop. In that time, Walker and X-15 Ship 3 covered 305 miles in ground range. The mission was Ship No. 3’s 22nd flight and the 91st of the X-15 Program.

For Joseph Albert Walker, the 22nd of August 1963 marked his 25th and last flight in an X-15 cockpit. The mission qualified him for Astronaut Wings since he had exceeded the 328,000 foot (100 km) FAI/NASA standard set for such a distinction. Ironically, the historic record indicates that Joe Walker never officially received Astronaut Wings for this flight in which the X-15 design altitude was exceeded by over 100,000 feet.

Fifty-six years ago to the day, USAF Captain Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. successfully completed a daring parachute jump from 102,800 feet (19.5 miles). The historic bailout took place over the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico.

Kittinger’s jump was the final mission of the three-jump Project Excelsior flight research effort which focused on manned testing of the Beaupre Multi-Stage Parachute Parachute (BMSP). The system was being developed to provide USAF pilots with a means of survival from an extreme altitude ejection.

Transport to jump altitude was via a 3-million cubic foot helium balloon. Kittinger rode in an open gondola. He was protected from the harsh environment by an MC-3 partial pressure suit as well as an assortment of heavy cold-weather clothing. Kittinger and his jump wardrobe and flight gear weighed a total of 313 pounds

The Excelsior III mission was launched just north of Alamogordo, New Mexico at 11:29 UTC on Tuesday, 16 August 1960. Ninety-three minutes later, Kittinger’s fragile balloon reached float altitude. At 13:12 UTC, Kittinger stepped out of the gondola and into space. As he did so, he said: “Lord, take care of me now!”

The historic record shows that Joe Kittinger experienced a free-fall that lasted 4 minutes and 36 seconds. During this time, he fell 85,300 feet (16.2 miles). Incredibly, Kittinger reached a maximum free-fall velocity of 614 miles per hour (Mach 0.92) passing through 90,000 feet.

The BMSP worked as advertised. Kittinger entered the cloud deck obscuring his Tularosa Basin landing point at 21,000 feet. Main parachute deployment occurred at 17,500 feet. Total elapsed time from bailout to touchdown was 13 minutes and 45 seconds.

While Joe Kittinger and the Excelsior team focused on flight testing technology critical to the survival of fellow aviators, a byproduct of their efforts were aviation records that stood for over 50 years. Those achievements include: highest parachute jump (102,800 feet), longest free-fall duration (4 minutes 36 seconds – this record still stands), and longest free-fall distance (85,300 feet).

Thirty-nine years ago this week, the Space Shuttle Orbiter Enterprise successfully completed the first free flight of the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) Program. NASA Astronauts Fred W. Haise, Jr. and Charles G. “Gordon” Fullerton were at the controls of the pathfinder orbiter vehicle (OV-101).

Developers of the Space Shuttle Orbiter faced the challenge of designing a vehicle capable of flight from 17,500 mph (Mach 28) at entry interface (400,000 ft) to 220 mph (Mach 0.3) at landing. Complicating this task was the fact that the Orbiter flew an unpowered, lifting entry that covered a distance of more than 4,400 nm. Once at the landing site, Shuttle pilots had a single opportunity to land the winged ship.

An Orbiter’s approach to the landing field is quite steep compared to that of a commercial airliner. Whereas the glide slope of the latter is around 2-3 degrees, the Orbiter’s flight path during approach is about 22 degrees below the horizon. Falling like a rock is an apt description of its flight state.

The Space Shuttle Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) involved a series of flight tests intended to verify the subsonic airworthiness and handling qualities of the Orbiter. Conducted at Edwards Air Force Base between February and October 1977, the ALT employed a modified Boeing 747 known as the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA). The Orbiter Enterprise was attached atop the SCA to hitch a ride to altitude.

The Shuttle ALT consisted of a total of thirteen (13) flight tests; five (5) Captive-Inactive (CI) tests, five (5) Captive-Active (CA) tests and three (3) Free Flight (FF) tests. CI testing was aimed at verifying the handling qualities of the SCA-Orbiter combination in flight. There was no crew was onboard the Orbiter for these tests. CA testing focused on preparing for the upcoming free flight series. A crew flew onboard the Orbiter which remained mated to the SCA.

The ALT Free Flights were where the rubber met the road so to speak. The Enterprise and her crew separated from the SCA at altitudes ranging from between 19,000 and 26,000 ft to test the Orbiter in free flight. Landings were made initially on Rogers Dry Lake (Runway 17) and ultimately on Edwards’ 15,000-ft concrete runway (Runway 22).

The Enterprise was flown in two (2) different configurations. The first involved the use of a tailcone fairing which streamlined the base region of the Orbiter. This increased the Orbiter’s lift-to-drag ratio which decreased the vehicle’s rate of descent. It also reduced the level of buffeting experienced by the SCA’s empennage while the Orbiter rode atop the carrier aircraft.

The second Enterprise configuration flown involved removal of the tailcone. This significantly reduced the Orbiter’s lift-to-drag ratio and correspondingly increased the rate of sink. Indeed, the Orbiter’s descent rate without the tailcone was roughly twice as high as that with the tailcone. Removal of the tailcone also markedly increased the buffet loads sustained by the SCA’s empennage.

ALT Free Flight No. 1 took place on Friday, 12 August 1977. With Fitzhugh L. Fulton, Jr. and Thomas C. McMurtry flying the SCA (N905NA), the Enterprise and her crew of Haise and Fullerton was carried to an altitude of 24,100 ft. At a speed of 310 mph in a slight dive, the big glider cleanly separated from the SCA. Just 321 seconds later, the Orbiter touched-down on Rogers Dry Lake at 213 mph.

ALT Free Flights No. 2-5 were successfully conducted over the next several months. Astronauts Joseph H. Engle and Richard H. Truly flew Enterprise on the second and fourth free flights while Haise and Fullerton manned the Orbiter’s cockpit on the third and fifth missions.

Enterprise flew without the tailcone during the last two ALT flights. As expected, the trip downstairs was rapid. Time of descent from 22,400 ft for Free Flight No. 4 was 154 seconds with a landing speed of 230 mph. Free Flight No. 5 took only 121 seconds to descend 19,000 ft and landed at 219 mph.

ALT Free Flight No. 5 was notable in that (1) the Enterprise made its first landing on concrete and (2) a Pilot-Induced Oscillation (PIO) occurred at initial touchdown. For a few tense moments Command Pilot Haise struggled to keep his skittish steed on the ground. Following several disturbing skips and bounces, the Enterprise finally settled down and rolled to a stop.

The Space Shuttle Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) were a necessary prelude to space for the Orbiter. Indeed, the ALT flights represent the first time that NASA’s new winged reentry vehicle took to the air. Having successfully demonstrated the ability to safely land an Orbiter, the next flight in the Space Shuttle Program would be STS-1 in April 1981. Interestingly, that 2-day mission would come to a successful conclusion when the Columbia landed on Rogers Dry Lake back at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

Sixty-two years ago this month, USAF Major Arthur W. “Kit” Murray set a new world altitude record of 90,440 feet in the rocket-powered Bell X-1A. In doing so, Murray reported that he could detect the curvature of the Earth from the apex of his trajectory.

The USAF/Bell X-1A was designed to explore flight beyond Mach 2. The craft measured 35.5 feet in length and had a wing span of 28 feet. Gross take-off weight was 16,500 pounds. Power was provided by an XLR-11 rocket motor which produced a maximum sea level thrust of 6,000 lbs. This powerplant burned 9,200 pounds of propellants (alcohol and liquid oxygen) in about 270 seconds of operation.

Similar to other early rocket-powered X-aircraft such as the Bell XS-1, Douglas D-558-II, Bell X-2 and North American X-15, the X-1A flew two basic types of high performance missions. That is, the bulk of the vehicle’s propulsive energy was directed either in the horizontal or in the vertical. The former was known as the speed mission while the latter was called the altitude mission.

On Saturday, 12 December 1953, USAF Major Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager flew the X-1A (S/N 48-1384) to an unofficial speed record of 1,650 mph (Mach 2.44). Moments after doing so, the X-1A went divergent in all three axes. The aircraft tumbled and gyrated through the sky. Control inputs had no effect. Yeager was in serious trouble. He could not control his aircraft and punching-out was not an option. The X-1A had no ejection seat.

Chuck Yeager took a tremendous physical and emotional beating for more than 70 seconds as the X-1A wildly tumbled. His helmet hit the canopy and cracked it. He struck the control column so hard that it was physically bent. His frantic air-to-ground communications were distinctly those of a man who was convinced that he was about to die.

As the X-1A tumbled, it decelerated and lost altitude. At 33,000 feet, a battered and groggy Yeager found himself in an inverted spin. The aircraft suddenly fell into a normal spin from which Yeager recovered at 25,000 feet over the Tehachapi Mountains situated northwest of Edwards. Somehow, Yeager managed to get himself and the X-1A back home intact.

The culprit in Yeager’s wide ride was the then little-known phenomenon identified as roll inertial coupling. That is, inertial moments produced by gyroscopic and centripetal accelerations overwhelmed aerodynamic control moments and thus caused the aircraft to depart controlled flight. Roll rate was the critical mechanism since it coupled pitch and yaw motion.

In the aftermath of Yeager’s near-death experience in the X-1A, the Air Force ceased flying speed missions with the aircraft. Instead, a series of flights followed in which the goal was to extract maximum altitude performance from the aircraft. USAF Major Arthur W. “Kit” Murray was assigned as the Project Pilot for these missions.

On Thursday, 26 August 1954, Kit Murray took the X-1A (S/N 48-1384) to a maximum altitude of 90,440 feet. This was new FAI record. Murray also ran into the same roll inertial coupling phenomena as Yeager. However, his experience was less tramatic than was Yeager’s. This was partly due to the fact that Murray had the benefit of learning from Yeager’s flight. This allowed him to both anticipate and know how to correct for this flight disturbance.

Murray’s achievement in the X-1A meant that the X-1A held the records for both maximum speed and altitude for manned aircraft. It did so until both records were eclipsed by the Bell X-2 in September of 1956.

Kit Murray was a highly accomplished test pilot who never received the public adulation and notoreity that Chuck Yeager did. He retired from the Air Force in 1960 after serving for 20 years in the military. Murray went on to a very successful career in engineering following his military service. Kit Murray lived to the age of 92 and passed from this earthly scene on Monday, 25 July 2011.

Fifty-five years ago this month, Mercury Seven Astronaut Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Jr. became the second American to go into space. Grissom’s suborbital mission was flown aboard a Mercury space capsule that he named Liberty Bell 7.

The United States first manned space mission was flown on Friday, 05 May 1961. On that day, NASA Astronaut Alan B. Shepard, Jr. flew a 15-minute suborbital mission down the Eastern Test Range in his Freedom 7 Mercury spacecraft. Known as Mercury-Redstone 3, Shepard’s mission was entirely successful and served to ignite the American public’s interest in manned spaceflight.

Shepard was boosted into space via a single stage Redstone rocket. This vehicle was originally designed as an Intermediate-Range ballistic Missile (IRBM) by the United States Army. It was man-rated (that is, made safer and more reliable) by NASA for the Mercury suborbital mission. A descendant of the German V-2 missile, the Redstone produced 78,000 lbs of sea level thrust.

Shepard’s suborbital trajectory resulted in an apogee of 101 nautical miles (nm). With a burnout velocity of 7,541 ft/sec, Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 263 nm downrange of its LC-5 launch site at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Shepard endured a maximum deceleration of 11 g’s during the reentry phase of the flight.

Mercury-Redstone 4 was intended as a second and confirming test of the Mercury spacecraft’s space-worthiness. If successful, this mission would clear the way for pursuit and achievement of the Mercury Program’s true goal which was Earth-orbital flight. All of this rested on the shoulders of Gus Grissom as he prepared to be blasted into space.

Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft was a better ship than Shepard’s steed from several standpoints. Liberty Bell 7 was configured with a large centerline window rather than the two small viewing ports featured on Freedom 7. The vehicle’s manual flight controls included a new rate stabilization system. Grissom’s spacecraft also incorporated a new explosive hatch that made for easier release of this key piece of hardware.

Mercury-Redstone 4 (MR-4) was launched from LC-5 at Cape Canaveral on Friday, 21 July 1961. Lift-off time was 12:20:36 UTC. From a trajectory standpoint, Grissom’s flight was virtually the same as Shepard’s. He found the manual 3-axis flight controls to be rather sluggish. Spacecraft control was much improved when the new rate stabilization system was switched-on. The time for retro-fire came quickly. Grissom invoked the retro-fire sequence and Liberty Bell 7 headed back to Earth.

Liberty Bell 7’s reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere was conducted in a successful manner. The drogue came out at 21,000 feet to stabilize the spacecraft. Main parachute deployed occurred at 12,300 feet. With a touchdown velocity of 28 ft/sec, Grissom’s spacecraft splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 32 seconds after lift-off. America now had both a second spaceman and a second successful space mission under its belt.

Following splashdown, Grissom logged final switch settings in the spacecraft, stowed equipment and prepared for recovery as several Marine helicopters hovered nearby. As he did so, the craft’s new explosive hatch suddenly blew for no apparent reason. Water started to fill the cockpit and the surprised astronaut exited the spacecraft as quickly as possible.

Grissom found himself outside his psacecraft and in the water. He was horrfied to see that Liberty Bell 7 was in imminent peril of sinking. The primary helicopter made a valiant effort to hoist the spacecraft out of the water, but the load was too much for it. Faced with losing his vehicle and crew, the pilot elected to release Liberty Bell 7 and abandon it to a watery grave.

Meanwhile, Grissom struggled just to stay afloat in the churning ocean. The prop blast from the recovery helicopters made the going even tougher. Finally, Grissom was able to retrieve and get himself into a recovery sling provided by one of the helicopters. He was hoisted aboard and subsequently delivered safely to the USS Randolph.

In the aftermath of Mercury-Redstone 4, accusations swirled around Grissom that he had either intentionally or accidently hit the detonation plunger that activated the explosive hatch. Always the experts on everything, especially those things which they have little comprehension of, the denizens of the press insinuated that Grissom must have panicked. Grissom steadfastly asserted to the day that he passed from this earthly scene that he did no such thing.

Liberty Bell 7 rested at a depth of 15,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean until it was recovered by a private enterprise on Tuesday, 20 July 1999; a day short of the 38th anniversary of Gus Grissom’s MR-4 flight. The beneficiary of a major restoration effort, Liberty Bell 7 is now on display at the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center. The spacecraft’s explosive hatch was never found.

As for Gus Grissom, ultimate vindication of his character and competence came in the form of his being named by NASA as Commander for the first flights of Gemini and Apollo. Indeed, Grissom and rookie astronaut John W. Young successfully made the first manned Gemini flight in March of 1965 during Gemini-Titan 3. Later, Grissom, Edward H. White II and Roger B. Chaffee trained as the crew of Apollo 1 which was slated to fly in early 1967. History records that their lives were cut short in the tragic and infamous Apollo 1 Spacecraft Fire of Friday, 27 January 1967.

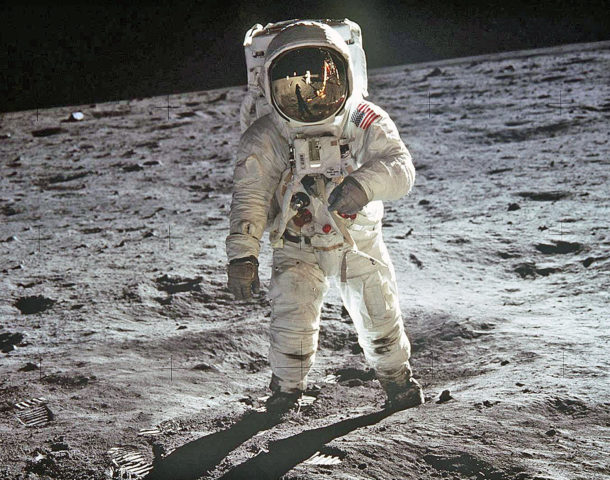

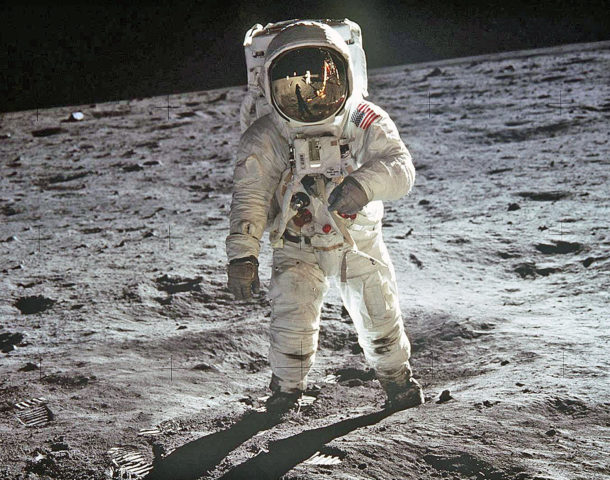

Forty-seven years ago today, the United States of America landed two men on the surface of the Moon. This feat marked the first time in history that men from the planet Earth set foot on another celestial body in the solar system.

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle landed in the Sea of Tranquility region of the Moon on Sunday, 20 July 1969 at 20:17:40 UTC. Less than seven hours later, Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. became the first human beings to walk upon Earth’s closest neighbor. Fellow crew member Michael Collins orbited high overhead in the Command Module Columbia.

As Apollo 11 commander, Neil A. Armstrong was accorded the privilege of being the first man to step foot upon the Moon. As he did so, Armstrong spoke these words: “That’s one small step for Man; one giant leap for Mankind”. He had intended to say: “That’s one small step for ‘a’ man; one giant leap for Mankind”.

Armstrong and Aldrin explored their Sea of Tranquility landing site for about two and a half hours. Total lunar surface stay time was 22 hours and 37 minutes. The Apollo 11 crew left a plaque affixed to one of the legs of the Lunar Module’s descent stage which read: “Here Men From the Planet Earth First Set Foot Upon the Moon; July 1969, A.D. We Came in Peace for All Mankind”.

Following a successful lunar lift-off aboard the Eagle, Armstrong and Aldrin rejoined Collins in lunar orbit. Approximately seven hours later, the Apollo 11 crew rocketed out of lunar orbit to begin the quarter million mile journey back to Earth. Columbia splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean at 16:50:35 UTC on Thursday, 24 July 1969. Total mission time was 195 hours, 18 minutes, and 35 seconds.

With completion of the flight of Apollo 11, the United States of America fulfilled President John F. Kennedy’s 25 May 1961 call to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth before the decade of the 1960’s was out. It had taken 2,982 demanding days and a great deal of national treasure to do so.

Mission Accomplished, Mr. President.

Twenty-seven years ago this month, the USAF/Northrop B-2 Stealth Strategic Bomber flew for the first time. The aircrew for the B-2’s maiden trip upstairs included Northrop B-2 Division Chief Test Pilot Bruce J. Hinds (command pilot) and B-2 Combined Test Force Commander USAF Col. Richard S. Couch (co-pilot).

The B-2 traces it lineage to a variety of Northrop flying wing aircraft including the piston-powered YB-35 and jet-propelled YB-49. These 1940’s-era experimental aircraft served as important stepping stones in the evolution of large flying wing technology.

An all-wing aircraft represents an aerodynamically-optimal configuration from the standpoint of high lift, low drag and therefore high lift-to-drag ratio. These favorable aerodynamic attributes translate to high levels of range performance and load-carrying capability. In addition, the type’s high aspect ratio and slim profile provide for more favorable low observable characteristics than traditional fuselage-wing-empennage aircraft geometries.

Arguably the most challenging aspects of creating an all-wing aircraft have to do with flight control and handling qualities. The crash of the second YB-49 flying wing in June of 1948 underscored the insufficiency of aerospace technology at that time to handle these design challenges. It was not until the advent of modern flight control avionics during the 1980’s that the full potential of a flying wing aircraft would be realized.

The B-2 is only 69 feet in length, but has a wing span of 172 feet and a wing area of 5,140 square feet. Gross take-off and empty weights are 336,500 lbs and 158,000 lbs, respectively. Embedded within the wings are a quartet of fuel-efficient F118-GE-100 turbofan engines, each generating 17,300 lbs of thrust. The aircraft has a top speed of about Mach 0.85, an unrefueled range of 6,000 nm and a service ceiling of 50,000 feet. Maximum ordnance load is 50,000 lbs.

B-2 AV-1 (Spirit of America; S/N 82-1066) took-off for the first time from Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California on Monday, 17 July 1989. Supported by F-16 chase aircraft, the majestic flying wing flew a 2 hour 12 minute test mission which concluded with a landing at nearby Edwards Air Force Base. As a first flight precaution, the entire mission was flown with the landing gear down.

The first B-2 airframe to enter the operational inventory was AV-8, the Spirit of Missouri (S/N 88-0329). It did so on 31 March 1994. While initial plans called for a production run of 132 aircraft, only 21 B-2 airframes were actually built. With the 2008 loss of the Spirit of Kansas shortly after take-off from Andersen Air Force Bas in Guam, 20 of these aircraft remain in active service today.

Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri serves as Air Force’s home for the B-2. From there, the majestic flying wing has flown a multitude of global strike missions to deliver a variety of ordnance with pinpoint accuracy. To date, the B-2 has successfully engaged targets in Kosovo, Afganistan, Iraq and Libya. The B-2 is truly a technological marvel and a national defense asset. As such, it may be expected to be a vital part of the Air Force’s active inventory for decades to come.

Thirty-four years ago this week, the Space Shuttle Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base to successfully conclude the fourth orbital mission of the Space Transportation System. Columbia’s return to earth added a special touch to the celebration of America’s 206th birthday.

STS-4 was NASA’s fourth Space Shuttle mission in the first fourteen months of Shuttle orbital flight operations. The two-man crew consisted of Commander Thomas K. Mattingly, Jr. and Pilot Henry W. Hartsfield who were both making their first Shuttle orbital mission. STS-4 marked the last time that a Shuttle would fly with a crew of just two.

STS-4 was launched from Cape Canaveral’s LC-39A on Sunday, 27 June 1982. Lift-off was exactly on-time at 15:00:00 UTC. Interestingly, this would be the only occasion in which a Space Shuttle would launch precisely on-time. The Columbia weighed a hefty 241,664 lbs at launch.

Mattingly and Hartsfield spent a little over seven (7) days orbiting the Earth in Columbia. The orbiter’s cargo consisted of the first Getaway Special payloads and a classified US Air Force payload of two missile launch-detection systems. In addition, a Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES) and the Mono-Disperse Latex Reactor (MLR) were flown for a second time.

The Columbia crew conducted a lightning survey using manual cameras and several medical experiments. Mattingly and Hartsfield also maneuvered the Induced Environment Contamination Monitor (IECM) using the Orbiter’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS). The IECM was used to obtain information on gases and particles released by Columbia in flight.

On Sunday, 04 July 1982, retro-fire started Columbia on its way back to Earth. Touchdown occurred on Edwards Runway 22 at 16:09:31 UTC. This landing marked the first time that an Orbiter landed on a concrete runway. (All three previous missions had landed on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards.) Columbia made 112 complete orbits and traveled 2,537,196 nautical miles during STS-4.

The Space Shuttle was declared “operational” with the successful conduct of the first four (4) shuttle missions. President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan even greeted the returning STS-4 flight crew on the tarmac. However, as history has since taught us, manned spaceflight still comes with a level of risk and danger that exceeds that of military and commercial aircraft operations. It will be some time before a manned space vehicle is declared operational in the desired sense.

Forty-nine years ago today, USAF Major William F. “Pete” Knight made an emergency landing in X-15 No. 1 at Mud Lake, Nevada. Knight somehow managed to save the hypersonic aircraft following a complete loss of electrical power as the vehicle passed through 107,000 feet during the climb.

The famed X-15 Program conducted 199 flights between June 1959 and October 1968. North American Aviation (NAA) built three (3) X-15 aircraft. Twelve (12) men from NAA, USAF and NASA flew the X-15. Eight (8) pilots received astronaut wings for flying the X-15 beyond 250,000 feet. One (1) aircraft and one (1) pilot were lost during flight test.

The X-15 flew as fast as 4,520 mph (Mach 6.7) and as high as 354,200 feet. The basic airframe measured 50 feet in length, featured a wing span of 22 feet and had a gross weight of 33,000 pounds. The type’s Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine burned anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen to produce a sea level thrust of 57,000 pounds. The X-15 used both 3-axis aerodynamic and ballistic flight controls.

An X-15 mission was fast-paced. Flight time from B-52 drop to unpowered landing was typically 10 to 12 minutes in duration. The pilot wore a full pressure suit and experienced 6 to 7 G’s during pull-out from max altitude. There really was no such thing as a routine X-15 mission. However, all X-15 missions had one factor in common; high danger.

On Thursday, 29 June 1967, X-15 No. 1 (S/N 56-6670) made its 73rd and the X-15 Program’s 184th free flight. Launch took place at 1828 UTC as the NASA B-52B launch aircraft (S/N 52-0008) flew at Mach 0.82 and 40,000 feet near Smith Ranch, Nevada. Knight, making his 10th X-15 flight, quickly ignited the XLR-99 and started the climb upstairs.

The X-15 was performing well and Knight was enjoying the flight until 67.6 seconds into a planned 87 second XLR-99 burn. That’s when the engine suddenly quit. A couple of heartbeats later, the Stability Augmentation System (SAS) failed, the Auxiliary Power Units (APU’s) ceased operating, the X-15’s generators stopped functioning and the cockpit lights went out. This was the total hit; a complete power failure.

Pete Knight was now just along for the ride. No thrust to power the aircraft. No electrical power to run onboard systems. No hydraulics to move flight controls. Even the reaction controls appeared inoperative. The X-15 continued upward, but it wallowed aimlessly in the low dynamic pressure of high altitude flight. At this point, Knight considered taking his chances and punching-out.

The X-15 went over the top at 173,000 feet. On the way downhill, Knight was able to get some electrical power from the emergency battery. This meant that he now had some hydraulic power and could utilize the X-15’s flight control surfaces. Knight next tried to fire-up the APU’s. The right APU would not respond. The left APU fired, but the its generator would not engage.

As the X-15 descended and the dynamic pressure built-up, Knight was able to maneuver his stricken X-15. He headed for Mud Lake in a sustained 6-G turn. As he leveled off at 45,000 feet, Knight instinctively knew he could now make the east shore of the Nevada dry lake. But it was tough work to fly the X-15. Knight ended-up using both hands to fly the airplane; one hand on the side stick and one hand on the center stick.

While Knight was trying to get his airplane down on the ground in one piece, only he and his Maker knew his whereabouts. The X-15 flight test team certainly didn’t, since Knight’s radio, telemetry and radar transponder were now inop. Further, the X-15 was not being skinned tracked at the time of the electrical anomaly. Just before he touched-down at Mud Lake, Knight’s X-15 was spotted by NASA’s Bill Dana who was flying a F-104N chase aircraft.

Pete Knight made a good landing at Mud Lake. The X-15 slid to a stop. After a struggle with the release mechanism, he managed to get the canopy open. Hot and soaked with perspiration, Knight somehow removed his own helmet. A ground crewman usually did that for him. But there were no flight support people at his X-15 landing site on this day.

As he attempted to get out of the X-15 cockpit, Knight pulled an emergency release. To his surprise, the headrest blew off, bounced off the canopy and smacked him square in the head. Undeterred, Knight got out of the cockpit and onto terra firma. In the meantime, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules had landed at Mud Lake. Wearily, Pete Knight got onboard and returned to Edwards Air Force Base.

Post-flight investigation revealed that the most probable source of the X-15’s electrical failure was arcing in a flight experiment system. This system had been connected to the X-15’s primary electrical bus. The solution was to connect flight experiments to the secondary electrical bus.

Reflecting on Knight’s amazing recovery from almost certain disaster, long-time NASA flight test manager Paul Bickle claimed the fete was among the most impressive of the X-15 Program. Indeed, it was Pete Knight’s clearly uncommon piloting skill and calmness under pressure that gave him the edge.