Thirteen years ago today, the NASA X-43A scramjet-powered flight research vehicle reached a record speed of over 4,600 mph (Mach 6.83). The test marked the first time in the annals of aviation that a flight-scale scramjet accelerated an aircraft in the hypersonic Mach number regime.

NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X in 1996. The fundamental goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10.

The scramjet is a key to sustained hypersonic flight within the earth’s atmosphere. Whereas rockets are capable of producing large thrust magnitudes, the amount of thrust per unit propellant mass is low. In part, this is because a rocket has to carry its own fuel and oxidizer. A scramjet is a much more efficient producer of thrust in that it only has to carry its fuel and uses the atmosphere as its oxidizer source.

Rocket technology is a highly developed discipline with a deep experience and application base. In contradistinction, flight-scale scramjet technology is still in a developmental stage. Considerations such as initiating and sustaining stable combustion is a supersonic stream, efficient conversion of fuel chemical energy to kinetic energy, and optimal integration of the scramjet propulsion system into a hypersonic airframe are among the challenges that face designers.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed nearly 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The second flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 27 March 2004. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 20:40 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 21:59:58 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership. Following a 5 second free fall, rocket motor ignition occurred and the HXLV initiated a pull-up to start its climb and acceleration to the test window. It took the HXLV about 90 seconds to reach a speed of slightly over Mach 7.

Following rocket motor burnout and a brief coast period, the HXRV (X-43A) successfully separated from the Pegasus booster at 94,069feet and Mach 6.95. The HXRV scramjet was operative by Mach 6.83. Supersonic combustion and thrust production were successfully achieved. Total power-on flight duration was approximately 11 seconds.

As the X-43A decelerated along its post-burn descent flight path, the aircraft performed a series of data gathering flight maneuvers. A vast quantity of high-quality aerodynamic and flight control system data were acquired for Mach numbers ranging from hypersonic to transonic. Finally, the X-43A impacted the Pacific Ocean at a point about 450 nautical miles due west of its launch location. Total flight time was approximately 15 minutes.

The HYPER-X Program made history that day in late March 2004. Supersonic combustion and thrust production of an airframe-integrated scramjet were achieved for the first time in flight; a goal that dated back to before the X-15 Program. Along the way, the X-43A established a speed record for airbreathing aircraft and earned a Guinness World Record for its efforts.

Seventy years ago this month, the USAF/North American XB-45 Tornado bomber made its inaugural test flight at Muroc Army Air Field, California. The type would go on to become the United States’ first operational turbojet-powered bomber.

The XB-45 measured 74 feet in length, had a wingspan of 89.5 feet and a GTOW of 82,000 lbs. Power was provided by a quartet of Allison J35-A-7 turbojets producing a rather paltry 16,000 lbs of sea level thrust. With a maximum speed at sea level of roughly 500 mph, the service ceiling of the XB-45 was 37,600 feet.

A trio of XB-45 prototype aircraft were manufactured for the Air Force by North American. Serial numbers 45-59479, 45-59480, and 45-59481 were assigned to the three ships. Air crew consisted of two pilots who sat in tandem. The XB-45 flight test program included slightly more than 130 flights.

The first flight of the XB-45, Ship No. 1 (S/N 45-59479) took place on Monday, 17 March 1947 at Muroc Army Air Field, California. North American test pilot George W. Krebs was in the cockpit of the prototype bomber. The one-hour test hop was restricted to low speeds because the landing gear doors could not be fully closed.

Production versions of the Tornado included the B-45A, B-45C, and RB-45C. These aircraft were powered by General Electric J-47 turbojets and represented a great improvement relative to the XB-45 in terms of performance, operability, and reliability. Aircrew for the production Tornado variants included a pilot, co-pilot, bombardier-navigator, and tail gunner.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) used the RB-45C to fly clandestine recon missions over the Soviet Union between 1952 and 1954. Known as Operation Ju-jitsu, RB-45C aircrews gathered electronic and photographic intelligence information critical to the Free World’s defense posture. These high-risk RB-54C missions ultimately led to development of more capable recon aircraft; the Lockheed U-2 and SR-71.

The B-45 and RB-45 Tornado served in the Strategic Air Command (SAC) from 1950 through 1959. The B-45A holds the distinction of being USAF’s first operational jet-powered bomber as well as the first multi-jet bomber to be air-refueled. It was also the first jet bomber to carry and drop a nuclear weapon.

Fifty-nine years ago this week, the United States Navy Vanguard Program registered its first success with the orbiting of the Vanguard 1 satellite. The diminutive orb was the fourth man-made object to be placed in Earth orbit.

The Vanguard Program was established in 1955 as part of the United States involvement in the upcoming International Geophysical Year (IGY). Spanning the period between 01 July 1957 and 31 December 1958, the IGY would serve to enhance the technical interchange between the east and west during the height of the Cold War.

The overriding goal of the Vanguard Program was to orbit the world’s first satellite sometime during the IGY. The satellite was to be tracked to verify that it achieved orbit and to quantify the associated orbital parameters. A scientific experiment was to be conducted using the orbiting asset as well.

Vanguard was managed by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). This gave the Vanguard Program a distinctly scientific (rather than military) look and feel. Something that the Eisenhower Administration definitely wanted to project given the level of Cold War tensions.

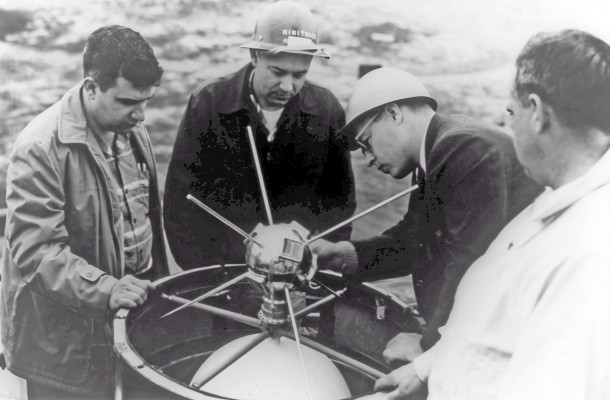

The key elements of Vanguard were the Vanguard launch vehicle and the Vanguard satellite. The Vanguard 3-stage launch vehicle, manufactured by the Martin Company, evolved from the Navy’s successful Viking sounding rocket. The Vanguard satellite was developed by the NRL.

On Friday, 04 October 1957, the Soviet Union orbited the world’s first satellite – Sputnik I. While the world was merely stunned, the United States was quite shocked by this achievement. A hue and cry went out across the land. How could this have happened? Will the Soviets now unleash nuclear weapons on us from space? And most hauntingly – where is our satellite?

In the midst of scrambling to deal with the Soviet’s space achievement, America would receive another blow to the national solar plexus on Sunday, 03 November 1957. That is the day that the Soviet Union orbited their second satellite – Sputnik II. And this one even had an occupant onboard; a mongrel dog name Laika.

The Vanguard Program was now uncomfortably in the spotlight. But it really wasn’t ready at that moment to be America’s response to the Soviets. After all, Vanguard was just a research program. While the launch vehicle was developing well enough, it certainly was not ready for prime time. The Vanguard satellite was a new creation and had never been used in space.

History records that the first American satellite launch attempt on Friday, 06 December 1957 went very badly. The launch vehicle lost thrust at the dizzying height of 4 feet above the pad, exploded when it settled back to Earth whereupon it consumed itself in the resulting inferno. Amazingly, the Vanguard satellite survived and was found intact at the edge of the launch pad.

Faced with a quickly deteriorating situation, America desperately turned to the United States Army for help. Wernher von Braun and his team at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) responded by orbiting Explorer I on Friday, 31 January 1958. America was now in space!

The Vanguard Program regrouped and attempted to orbit a Vanguard satellite on Wednesday, 05 February 1958. Fifty-seven seconds into flight the launch vehicle exploded. Vanguard was now 0 for 2 in the satellite launching business. Undeterred, another attempt was scheduled for March.

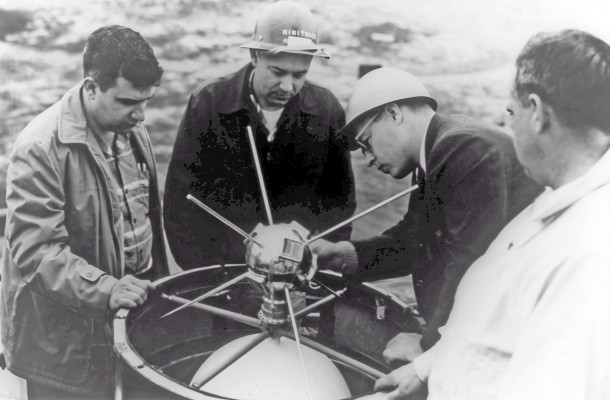

Monday, 17 March 1958 was a good day for the Vanguard Program and the United States of America. At 12:51 UTC, Vanguard launch vehicle TV-4 departed LC-18A at Cape Canaveral, Florida and placed the Vanguard 1 satellite into a 2,466-mile x 406-mile elliptical orbit. On this Saint Patrick’s Day, Vanguard registered its first success and America had a second satellite orbiting the Earth.

Whereas the Soviet satellites weighed hundreds of pounds, Vanguard 1 was tiny. It was 6.4-inches in diameter and weighed only 3.25 pounds. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev mockingly referred to it as America’s “grapefruit satellite”. Small maybe, but mighty as well. Vanguard 1 went on to record many discoveries that helped write the book on spaceflight.

Khrushchev is gone and all of those big Sputniks were long ago incinerated in the fire of reentry. Interestingly, the “grapefruit satellite” is still in space. Indeed, it is the oldest satellite in Earth orbit. As of this writing, Vanguard 1 has completed over 200,000 Earth revolutions and traveled more than 5.7 billion nautical miles since 1958. It is expected to stay in orbit for another 240 years. Not too bad for a grapefruit.

Fifty-nine years ago this month, the first zero-length launch of an USAF/North American F-100D Super Sabre took place at Edwards Air Force Base, California. North American Test Pilot Albert “Al” R. Blackburn was at the controls of the experimental rocket-propelled test aircraft.

Zero-Length Launch (ZLL) was a concept pioneered by the United States Air Force for quickly getting aircraft into the air without the need for a conventional runway take-off. The idea was to launch the aircraft via rocket power from a standing start. Shortly after launch, the aircraft was at flight speed and the dead rocket booster was jettisoned.

The ZLL concept was typical of attempts by USAF to gain tactical advantage over the Soviet Union in any way possible during the Cold War era. ZLL held the promise of getting nuclear-armed combat aircraft airborne in the event that airfield runways were rendered useless due to enemy attack.

The ZLL mission was envisioned as one-way trip. Once airborne, a pilot was expected to fly to the target, deliver his nuclear weapon and then fend for himself. Survival options included finding a friendly field to land at or eject over non-hostile territory. Either way, the pilot’s chances of things working out well were not good.

The first attempt to test the ZLL concept dates back to 1953 when USAF employed the straight-wing USAF/Republic F-84G Thunderjet in the ZELMAL Program. ZELMAL stood for Zero Length Launch/ Mat Landing. This last part involved the aircraft making a wheels-up landing on an inflatable rubber mat that measured 800 ft x 80 ft x 3 ft.

Piloted ZELMEL flight tests were conducted at Edwards Air Force Base in 1954. The results were not particularly encouraging. Understandably, the mat landing was a rough go. The landing mat was heavily damaged on the first test and the pilot sustained back injuries that required months of recovery time. Subsequent flight tests showed ZELMAL to be essentially unworkable as then conceived.

USAF reprised the ZLL concept in 1958 with the F-100D Super Sabre. Gone was the mat landing part of the operation. The aircraft would make a normal wheels down landing if it got airborne successfully. Launch motive power was provided by a single Rocketdyne XM-34 solid rocket booster that generated 132,000 lbs of thrust for 4 seconds. At burnout of the boost motor, the F-100D was 400 feet above ground level and traveling at 275 mph. The booster was then jettisoned and the aircraft continued to accelerate under turbojet power.

The first flight test of the F-100 ZLL aircraft (S/N 56-2904) took place on Wednesday, 26 March 1958. The aircraft was launched from the south end of Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The test aircraft carried a pylon-mounted 275-gallon fuel tank on the right wing and a simulated nuclear store on a pylon under the left wing. North American Aviation’s Albert “Al” R. Blackburn was the assigned test pilot.

The first F-100 ZLL flight was entirely successful. Blackburn reported an exceptionally smooth ride on the rocket and an uneventful transition to turbojet-powered flight. While the boost motor struck the belly of the aircraft during departure and caused some superficial damage, the separation was otherwise successful. After a brief flight, Blackburn safely landed his steed on the concrete.

The first flight success of the ZLL Super Sabre was followed several weeks later by loss of aircraft 56-2904. Although the launch phase was proper, the boost motor hung-up on its support bolts and could not be jettisoned following burnout. Blackburn’s attempts to shake the dead motor free from the aircraft proved futile. Since a successful landing was not possible, the pilot was forced to eject.

A total of fourteen (14) more F-100D ZLL flights took place at Edwards through October of 1958. Although these flights proved ZLL to be a viable means for getting a combat aircraft airborne without the use of a conventional runway take-off, USAF ultimately judged the concept to be too impractical and logistically burdensome to field. This in spite of the fact that a total of 148 F-100D Super Sabre aircraft were eventually modified for the ZLL mission.

Sixty-one years ago this month, the No. 1 USAF/Martin XB-51 light attack bomber prototype crashed during take-off from El Paso International Airport in Texas. The cause of the mishap was attributed to premature rotation of the aircraft leading to an unrecoverable stall.

A product of the post-WWII 1940’s, the Martin XB-51 was envisioned as a jet-powered replacement for the piston-driven Douglas A-26 Invader. The swept-wing XB-51 utilized a unique propulsion system which consisted of a trio of General Electric J47 turbojets. Demonstrated top speed was 560 knots at sea level.

The XB-51 was a good-sized airplane. With a length of 85 feet and a wing span of 53 feet, the XB-51 had a nominal take-off weight of around 56,000 lbs. The wings were swept 35 degrees aft and incorporated 6 degrees of anhedral. The latter feature was utilized to counter the large dihedral effect produced by the type’s tee-tail.

A pair of XB-51 aircraft were built by Martin for USAF. Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-0685) first took to the air in October of 1949 followed by the flight debut of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) in April of 1950. The air crew consisted of a pilot who sat underneath a large, clear canopy and a navigator housed within the fuselage.

While the XB-51 flew hundreds of hours in flight test and made many lasting contributions to the aviation field, the aircraft never went into production. This fate was primarily the result of having lost a head-to-head competitive fly-off against the English Electric Canberra B-57A light attack bomber in 1951.

The No. 1 XB-51 aircraft was lost on Sunday, 25 March 1956 during take-off from El Paso International Airport. The mishap aircraft accelerated more slowly than normal and with the end of the runway coming up quickly, the pilot rotated the aircraft in a attempt to get airborne. Unfortunately, the rotation was premature and the wing stalled. The aircraft exploded on impact and the crew of USAF Major James O. Rudolph and Staff-Sargent Wilbur R. Savage were killed.

The loss of the No. 1 XB-51 was preceded by the destruction of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) on Friday, 09 May 1952. That tragedy occurred during low-altitude aerobatic maneuvers at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The pilot, USAF Major Neil H. Lathrop, perished in the resulting post-impact explosion and inferno.

As a footnote, the historical record reveals that the XB-51 was never assigned an official nickname by the Air Force. However, it was unofficially referred to in some aviation circles as the Panther. Due to its prominently-long fuselage, the less majestic monicker of “Flying Cigar” was sometimes used as well.

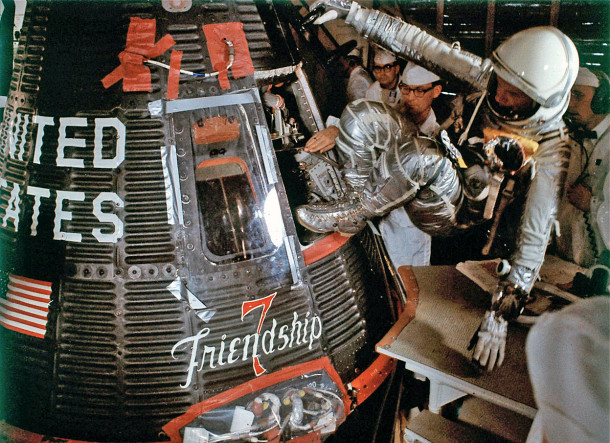

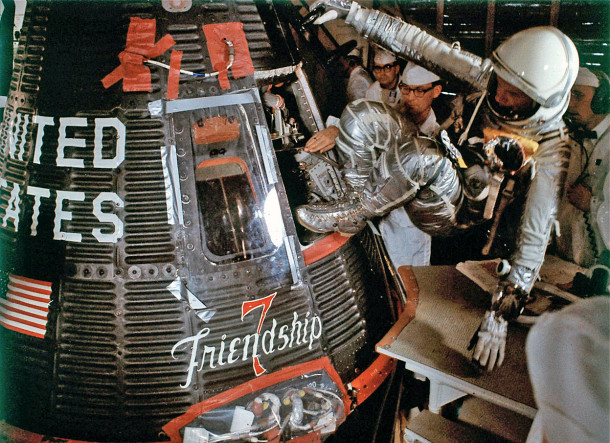

Fifty-five years ago today, Project Mercury Astronaut John Herschel Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn’s spacecraft name and mission call sign was Friendship 7.

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 14 at 14:47:39 UTC on Tuesday, 20 February 1962. It was the first time that the Atlas LV-3B booster was used for a manned spaceflight.

Three-hundred and twenty seconds after lift-off, Friendship 7 achieved an elliptical orbit measuring 143 nm (apogee) by 86 nm (perigee). Orbital inclination and period were 32.5 degrees and 88.5 minutes, respectively.

The most compelling moments in the United States’ first manned orbital mission centered around a sensor indication that Glenn’s heatshield and landing bag had become loose at the beginning of his second orbit. If true, Glenn would be incinerated during entry.

Concern for Glenn’s welfare persisted for the remainder of the flight and a decision was made to retain his retro package following completion of the retro-fire sequence. It was hoped that the 3 flimsy straps holding the retro package would also hold the heatshield in place.

During Glenn’s return to the atmosphere, both the spent retro package and its restraining straps melted in the searing heat of re-entry. Glenn saw chunks of flaming debris passing by his spacecraft window. At one point he radioed, “That’s a real fireball outside”.

Happily, the spacecraft’s heatshield held during entry and the landing bag deployed nominally. There had never really been a problem. The sensor indication was found to be false.

Friendship 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at a point 432 nm east of Cape Canaveral at 19:43:02 UTC. John Glenn had orbited the Earth 3 times during a mission which lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds. In short order, spacecraft and astronaut were successfully recovered aboard the USS Noa.

John Glenn became a national hero in the aftermath of his 3-orbit mission aboard Friendship 7. It seemed that just about every newspaper page in the days following his flight carried some sort of story about his historic fete. Indeed, it is difficult for those not around back in 1962 to fully comprehend the immensity of Glenn’s flight in terms of what it meant to the United States.

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. passed away on 08 December 2016 at the age of 95. His trusty Friendship 7 spacecraft is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Fifty-eight years ago this month, the U.S. Navy’s first production Martin P6M-2 SeaMaster flyingboat took-off from Chesapeake Bay on its maiden flight. Martin chief test pilot George A. Rodney was at the controls of the 4-man, swept-wing naval bomber as it took to the skies on Tuesday, 17 February 1959.

Featuring a fuselage length of 134 feet, wingspan of 102 feet, and a wing leading edge sweep of 40 degrees, the P6M-2 had a GTOW of about 175,000 lbs. Armament included an ordnance load of 30,000 lbs and twin 20 mm, tail-mounted cannon. Power was provided by a quartet of Pratt and Whitney J75-P-2 turbojets; each delivering a maximum sea level thrust of 17,500 lbs.

The SeaMaster’s demonstrated top speed at sea level was in excess of Mach 0.90. This on-the-deck performance is comparable to that of the USAF/Rockwell B-1B Lancer and USAF/Northrup B-2 Spirit and exceeds that of the USAF/Boeing B-52 Stratofortress.

P6M pilots reported that the swept-wing ship handled well below 5,000 feet when flying at Mach numbers between 0.95 and 0.99. While designed for low altitude bombing and mine-laying, the aircraft was flown as high as 52,000 feet. As a result, the Navy even considered the SeaMaster as a nuclear weapons platform.

Despite the type’s impressive performance and capabilities, the SeaMaster Program was cancelled in August of 1959. Budgetary issues and the emerging Fleet Ballistic Missile System (Polaris-Poseidon-Trident) led to this decision. Loss of the P6M SeaMaster Program was devastating to the Glenn L. Martin Company and resulted in this notable aerospace business never again producing another aircraft.

Forty-two years ago this month, a USAF/McDonnell-Douglas F-15A Eagle Air Superiority Fighter zoomed to an altitude of 30 km (98,425 feet) in an elapsed time of 207.8 seconds from brake release. The pilot for the record-breaking mission was USAF Major Roger Smith.

Operation Streak Eagle was a mid-1970′s effort by the United States Air Force to set eight (8) separate time-to-climb records using the then-new McDonnell-Douglas F-15 Air Superiority Fighter. These record-setting flights originated from Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Starting on Thursday, 16 January 1975, the 19th pre-production F-15 Eagle aircraft (S/N 72-0119) was used to establish the following time-to-climb records during Operation Streak Eagle:

3 km, 16 January 1975, 27.57 seconds, Major Roger Smith

6 km, 16 January 1975, 39.33 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

9 km, 16 January 1975, 48.86 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

12 km, 16 January 1975, 59.38 seconds, Major Willard Macfarlane

15 km, 16 January 1975, 77.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

20 km, 19 January 1975, 122.94 seconds, Major Roger Smith

25 km, 26 January 1975, 161.02 seconds, Major David Peterson

The eighth and final time-to-climb record attempt of Operation Streak Eagle took place on Saturday, 01 February 1975. The goal was to set a new time-to-climb record to 30 km. The pilot was required to wear a full pressure suit for this mission.

At a gross take-off weight of 31,908 pounds, the Streak Eagle aircraft had a thrust-to-weight ratio in excess of 1.4. The aircraft was restrained via a hold-down device as the two Pratt and Whitney F100 turbofan engines were spooled-up to full afterburner.

Following hold-down and brake release, the Streak Eagle quickly accelerated during a low level transition following take-off. At Mach 0.65, Smith pulled the aircraft into a 2.5-g Immelman. The Streak Eagle completed this maneuver 56 seconds from brake release at Mach 1.1 and 9.75 km. Rolling the aircraft upright, Smith continued to accelerate the Streak Eagle in a shallow climb.

At an elapsed time of 151 seconds and with the aircraft at Mach 2.2 and 11.3 km, Smith executed a 4-g pull to a 60-degree zoom climb. The Steak Eagle passed through 30 km at Mach 0.7 in an elapsed time of 207.8 seconds. The apex of the zoom trajectory was about 31.4 km. With a new record in hand, Smith uneventfully recovered the aircraft to Grand Forks AFB.

Operation Streak Eagle ended with the capturing of the 30 km time-to-climb record. In December 1980, the aircraft was retired to the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. It is currently held in storage at the Museum and no longer on public display.

Fifty-nine years ago today, the United States successfully orbited the country’s first satellite. Known as Explorer I, the artificial moon went on to discover the system of radiation belts that surrounds the space environment of the Earth.

The Explorer I satellite was designed and fabricated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) under the direction of Dr. William J. Pickering. The satellite’s instrumentation unit measured 37.25 inches in length, 6.5 inches in diameter, and had a mass of only 18.3 lbs. With its burned-out fourth stage solid rocket motor attached, the total on-orbit mass of the pencil-like satellite was 30.8 lbs.

Explorer I was launched aboard a Jupiter-C (aka Juno I) launch vehicle from LC-26 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Friday, 31 January 1958. Lift-off at occurred at 22:48 EST (0348 UTC). With all four stages performing as planned, Explorer I was inserted into a highly elliptical orbit having an apogee of 1,385 nm and a perigee of 196 nm.

Arguably the most historic achievement of the Explorer I mission was the discovery of a system of charged particles or plasma within the magnetosphere of the Earth. These belts extend from an altitude of roughly 540 to 32,400 nm above mean sea level. Most of the plasma that forms these belts originates from the solar wind and cosmic rays. The radiation levels within the Van Allen Radiation Belts (named in honor of the University of Iowa’s Dr. James A. Van Allen) are such that spacecraft electronics and astronaut crews must be shielded from the adverse effects thereof.

Explorer I operational life was limited by on-board battery life and lasted a mere 111 days. However, it soldiered-on in orbit until reentering the Earth’s atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on Tuesday, 31 March 1970. During the 147 months it spent in space, Explorer I orbited the Earth more than 58,000 times. Data obtained and transmitted by the satellite contributed markedly to mankind’s understanding of the Earth’s space environment.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of Explorer I was that it was the first satellite orbited by the United States. Unknown to most today, this accomplishment was absolutely vital to America’s security, and indeed that of the free world, at the time. The Soviet Union had been first in space with the orbiting of the much larger Sputnik I and II satellites in late 1957. However, Explorer I showed that America also had the capability to orbit a satellite. History records that this capability would quickly grow and ultimately lead to the country’s preeminence in space.

Fifty years ago to the day, the Apollo 204 prime crew perished as fire swept through their Apollo Block I Command Module (CM). The Apollo 204 crew of Command Pilot Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White II and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee had been scheduled to make the first manned flight of the Apollo Program some three weeks hence.

On Friday, 27 January 1967, during a plugs-out ground test on LC-34 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, a fire broke out in the Apollo 204 spacecraft at 23:31:04 UTC (6:31:04 pm EST). Shortly after, a chilling cry was heard across the communications network from Astronaut Chaffee: “We’ve got a fire in the cockpit”.

Believed to have started just below Grissom’s seat, the fire quickly erupted into an inferno that claimed the men’s lives in less than 30 seconds. While each received extensive 3rd degree burns, death was attributed to toxic smoke inhalation.

The Apollo 204 fire was most likely brought about by some minor malfunction or failure in equipment or wire insulation. This failure, which was never positively identified, initiated a sequence of events that culminated in the conflagration.

The post-mishap investigation uncovered numerous defects in CM Block I design, manufacturing, and workmanship. The use of a (1) pure oxygen atmosphere pressurized to 16.7 psia and (2) complex 3-component hatch design (that took a minimum of 90 seconds to open) sealed the astronauts’ fate.

A haunting irony of the tragedy is that America lost her first astronaut crew, not in the sideral heavens, but in a spacecraft that was firmly rooted to the ground.