Fifty-five years ago this month, the fabled North American X-15 hit a speed of 3,590 mph (Mach 5.23) in a flight that reached an altitude of 103,300 feet. While decelerating through Mach 4.2, the nose gear of the aircraft unexpectedly deployed in flight.

The 114th powered flight of the legendary X-15 Program took place on Friday, 14 August 1964. USAF Major Robert A. Rushworth was at the controls of X-15 Ship No. 2 (S/N 56-6671). The mission would be Rushworth’s 22nd flight in the famed hypersonic aircraft.

X-15 drop from the NB-52A (S/N 52-0003) launch aircraft took place over Delamar Dry Lake, Nevada. Seconds later, Rushworth called for 100% power from the X-15’s XLR-99 liquid-fueled rocket engine as he pulled into a steep climb. He subsequently pushed-over and then leveled-off at 103,300 feet.

XLR-99 burnout occurred 80.3 seconds after ignition. At this juncture, the X-15 was traveling at 3,590 mph; better than 5 times the speed of sound. Following rocket motor burnout, the aircraft slowed and began to lose altitude under the influence of weight and aerodynamic drag.

As the Mach meter needle passed through Mach 4.2, Rushworth heard a loud bang from the airframe. The aircraft became hard to control as it gyrated in pitch, yaw and roll. Rushworth was equal to the moment and brought his troubled steed under control. However, the aircraft had an uncommanded sideslip and Rushworth had to use left aileron to hold the wings level.

Gathering his wits, Rushworth realized that the loud bang he heard was very similar to that which occurred when the nose gear was deployed in the landing pattern. Unaccountably, the X-15 nose gear had deployed in supersonic flight. An unsettling confirmation of Rushworth’s hypothesis came when the pilot spotted smoke, quite a bit of it, in the X-15 cockpit.

As Rushworth neared Edwards Air Force Base, chase aircraft caught up with him and confirmed that the nose gear was indeed down and locked. Further, the tires were so scorched from aerodynamic heating that they probably would disintegrate during touchdown on Rogers Dry Lake. They verily did.

Despite his tireless nose gear, Rushworth was able to control the rollout of his aircraft fairly well on the playa silt. He brought the X-15 to a stop and deplaned. Man and machine had survived to fly another day.

Post-flight analysis revealed that expansion of the X-15 fuselage due to aerodynamic heating was greater than expected. The nose gear door bowed or deformed outward more than anticipated as well. Together, these two anomalies caused the gear uplock hook to bend and release the nose gear. Fixes were subsequently made to Ship No. 2 to prevent a recurrence of the nose gear door deployment anomaly.

Rushworth next flew X-15 Ship No. 2 on Tuesday, 29 September 1964. He reached a maximum speed of 3,542 mph (Mach 5.2) at 97,800 feet. The nose gear door remained locked. However, while decelerating through Mach 4.5, Rushworth heard a bang that was less intense than the previous flight. This time, thermal stresses caused the nose gear door air scoop to deploy in flight. While the aircraft handled poorly, Rushworth managed to get it and himself back on the ground in one piece.

Following another redesign effort, Rushworth took to the air in X-15 Ship No. 2 on Thursday, 17 February 1965. He hit 3,539 mph (Mach 5.27) at 95,100 feet. On this occasion, both the nose gear door and nose gear door scoop remained in place. Unfortunately, the right main landing skid deployed at Mach 4.3 and 85,000 feet.

Thermal stresses were once again the culprit. Despite degraded handling qualities with the landing skid deployed, the valiant Rushworth safely landed the X-15. Upon deplaning, he is reported to have kicked the aircraft in a show of disgust and frustration. Unprofessional maybe, but certainly understandable.

Yet another redesign effort followed in the aftermath of the unexpected main landing skid deployment. This was the third consecutive mission for X-15 Ship No. 2 and Rushworth to experience a thermally-induced landing gear or landing skid deployment anomaly. Happily, subsequent flights of the subject aircraft were free of such vexing problems.

Fifty-six years ago today, NASA chief research pilot Joseph A. Walker flew X-15 Ship No. 3 (S/N 56-6672) to an altitude of 354,200 feet. This flight would mark the highest altitude ever achieved by the famed hypersonic research vehicle.

Carried aloft by NASA’s NB-52A (S/N 52-0003) mothership, Walker’s X-15 was launched over Smith Ranch Dry Lake, Nevada at 17:05:42 UTC. Following drop at around 45,000 feet and Mach 0.82, Walker ignited the X-15’s small, but mighty XLR-99 rocket engine and pulled his ship into a steep vertical climb.

The XLR-99 was run at 100 percent power for 85.8 seconds with burnout occurring around 176,000 feet on the way uphill. Maximum velocity achieved was 3,794 miles per hour which translates to Mach 5.58 at the burnout altitude. Following burnout of the XLR-99, Walker’s X-15 gained an additional 178,200 feet in altitude as it coasted to apogee.

Joe Walker went over the top at 354,200 feet (67 miles). Although he did not have much time for sight-seeing, the Earth’s curvature was strikingly obvious to the pilot as he started downhill from his lofty perch. Walker subsequently endured a hefty 5-g’s of eyeballs-in normal acceleration during the backside dive pull-out. The aircraft was brought to a wings-level attitude at 70,000 feet. Shortly after, Walker greased the landing on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The X-15 maximum altitude flight, in which the aircraft’s design altitude was exceeded by more than 100,000 feet, lasted 11 minutes and 8 seconds from drop to nose wheel stop. In that time, Walker and X-15 Ship 3 covered 305 miles in ground range. This mission was Ship No. 3’s 22nd flight and the 91st of the legendary X-15 Flight Research Program.

For Joseph Albert Walker, the 22nd of August 1963 marked his 25th and last flight in an X-15 cockpit. The mission qualified him for Astronaut Wings since he had exceeded the 328,000 foot (100 km) FAI/NASA standard set for such a distinction. However, it would be more than four decades after his historic mission that Walker would be officially be recognized as an astronaut. In a special ceremony conducted at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center on Tuesday, 23 August 2005, Joe Walker was posthumously awarded his Astronaut Wings.

Fifty-four years ago this month, NASA astronauts Leroy Gordon “Gordo” Cooper and Charles M. “Pete” Conrad set a new spaceflight endurance record during the flight of Gemini 5. It was the third of ten (10) missions in the historic Gemini spaceflight series. The motto for the mission was “Eight Days or Bust”.

The purpose of Project Gemini was to develop and flight-prove a myriad of technologies required to get to the Moon. Those technologies included spacecraft power systems, rendezvous and docking, orbital maneuvering, long duration spaceflight and extravehicular activity.

The Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the deboost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbit attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

Gemini-Titan V (GT-5) lifted-off at 13:59:59 UTC from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, 21 August 1965. The two-stage Titan II launch vehicle placed Gemini 5 into a 189 nautical mile x 87 nautical mile elliptical orbit.

A primary purpose of the Gemini 5 mission was to stay in orbit at least eight (8) days. This was the minimum time it would take to fly to the Moon, land and return to the Earth. Other goals of the Gemini 5 mission were to test the first fuel cells, deploy and rendezvous with a special rendezvous pod and conduct a variety of medical experiments.

Despite fuel cell problems, electrical system anomalies, reaction control system issues and the cancellation of various experiments, Gemini 5 was able to meet the goal of an 8-day flight. But it wasn’t easy. The last days of the mission were especially demanding since the crew didn’t have much to do. Pete Conrad called his Gemini 5 experience “8 days in a garbage can.”

On Sunday, 29 August 1965, Gemini 5 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 12:55:13 UTC. Mission elapsed time was 7 days, 22 hours, 55 minutes and 13 seconds. A new spaceflight endurance record.

Gemini 5 was Gordon Cooper’s last spaceflight. Cooper left NASA due to a deteriorating relationship with management. Pete Conrad flew three (3) more times in space. In particular, he commanded the Gemini 11, Apollo 12 and Skylab I missions. Indeed, Conrad’s Apollo 12 experience made him the third man to walk on surface of the Moon.

Fifty-nine years ago this month, USAF Captain Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr. successfully completed a daring parachute jump from 102,800 feet (19.5 miles). The historic bailout took place over the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico.

Kittinger’s jump was the final mission of the three-jump Project Excelsior flight research effort which focused on manned testing of the Beaupre Multi-Stage Parachute Parachute (BMSP). The system was being developed to provide USAF pilots with a means of survival from an extreme altitude ejection.

Transport to jump altitude was via a 3-million cubic foot helium balloon. Kittinger rode in an open gondola. He was protected from the harsh environment by an MC-3 partial pressure suit as well as an assortment of heavy cold-weather clothing. Kittinger and his jump wardrobe and flight gear weighed a total of 313 pounds

The Excelsior III mission was launched just north of Alamogordo, New Mexico at 11:29 UTC on Tuesday, 16 August 1960. Ninety-three minutes later, Kittinger’s fragile balloon reached float altitude. At 13:12 UTC, Kittinger stepped out of the gondola and into space. As he did so, he said: “Lord, take care of me now!”

The historic record shows that Joe Kittinger experienced a free-fall that lasted 4 minutes and 36 seconds. During this time, he fell 85,300 feet (16.2 miles). Incredibly, Kittinger reached a maximum free-fall velocity of 614 miles per hour (Mach 0.92) passing through 90,000 feet.

The BMSP worked as advertised. Kittinger entered the cloud deck obscuring his Tularosa Basin landing point at 21,000 feet. Main parachute deployment occurred at 17,500 feet. Total elapsed time from bailout to touchdown was 13 minutes and 45 seconds.

While Joe Kittinger and the Excelsior team focused on flight testing technology critical to the survival of fellow aviators, a byproduct of their efforts were aviation records that stood for over 50 years. Those achievements include: highest parachute jump (102,800 feet), longest free-fall duration (4 minutes 36 seconds – this record still stands), and longest free-fall distance (85,300 feet).

Sixty-four years ago this month, the USAF/Republic XF-84H experimental turboprop fighter took to the air on its maiden flight. The test sortie was flown at Edwards Air Force Base with Republic test pilot Henry G. “Hank” Beaird, Jr. at the controls.

The XF-84H was an experimental variant of Republic Aviation’s turbojet-powered F-84 Thunderstreak. An Allison XT40-A-1 turboprop engine, rated at 5,850 hp, served as the power source for this novel aircraft. The XT40 drove a variable-pitch, 3-blade, 12-foot diameter propeller at 3,000 rpm. Thrust level was changed by varying blade pitch.

Owing to its high rotational speed and large diameter, the outer 2 feet of the XF-84H propeller saw supersonic velocities. The shock waves that emanated from the prop produced a deafening wall of sound. The extreme sound level produced intense nausea and raging headaches in ground crewmen. As a result, the XF-84H was dubbed the Thunderscreech.

The prop wash from the aircraft’s powerful turboprop necessitated the use of a T-tail to keep the horizontal tail and elevator in clean air flow. The engine’s extreme torque was partially countered by differential deflection on the left and right wing flaps and by placement of the aircraft’s left wing root air intake a foot ahead of the its right intake.

A pair of XF-84H prototype aircraft (S/N 51-17059 and S/N 51-17060) was built by Republic Aviation. The inaugural flight of an XF-84H took place on Friday, 22 July 1955 at Edwards Air Force. This test hop, performed in Ship No. 1 (S/N 51-17059), was cut short by a forced landing.

A total of twelve (12) test flights were made in the two Thunderscreech prototypes; eleven (11) in Ship No. 1 and one (1) in Ship No. 2. Total flight time accumulated by these experimental airframes was 6 hours and 40 minutes. The majority of flights experienced forced landings for one reason or another.

The XF-84H suffered from reduced longitudinal stability and poor handling qualities. The aircraft was also plagued by frequent engine, hydraulic system, nose gear and vibration problems. Faced with the type’s obvious non-viability, USAF opted to cancel the XF-84H Program in September of 1956.

Historical records indicate that the XF-84H reached a top speed of 520 mph during its brief flight test life. This figure was a full 120 mph short of the aircraft’s design speed. Nonetheless, the XF-84H held the speed record for single-engine prop-driven aircraft until Monday, 21 August 1989. On that date, a specially modified Grumman F8F Bearcat established the existing record of 528.33 mph.

Fifty years ago today, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Alden Armstrong, Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Jr., and Michael Collins returned safely to the Earth to bring to a close the first space mission to land men on the lunar surface. With their safe return, President John F. Kennedy’s inspired national goal of landing men on the Moon and bringing them safely home before the end of the 1960’s was successfully accomplished.

The crew of Apollo 11 and their celestial chariot, Columbia, splashed-down in the Pacific Ocean at a point 812 nautical southwest of Hawaii. The epic journey to the Moon and back covered 952,700 nautical miles. Mission total elapsed time was 195 hours, 18 minutes, and 35 seconds.

Following splashdown, the Apollo 11 astronauts and their Command Module Columbia were brought aboard the USS Hornet (CV-12). Concerned that they would infect Earthlings with lunar pathogens, NASA quarantined the astronauts in the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), which was a converted vacation trailer.

The Hornet steamed for Hawaii and transferred the MQF for airlift to Ellington Air Force Base, Texas. Following landing, the MQF and its heroic occupants were transported to the Johnson Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas. Once there, the astronauts and several medical staff were transferred from the MQF to more substantial accommodations known as the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL).

Combined stay time in the MQF and LRL was 21 days. During their forced confinement, Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins debriefed the Apollo 11 mission, rested, and mused about their unforgettable experiences at the Moon.

The Apollo 11 astronauts were released from the LRL on Thursday, 13 August 1969, having never contracted nor transmitted a lunar disease.

Parenthetically, Apollo 11 brought the first geologic samples from the Moon back to Earth. Roughly 48 pounds of lunar rock samples were collected. Two primary types of rocks, basalts and breccias, were found at the Sea of Tranquility landing site. Subsequent analyses indicated that these samples neither contained water nor provided evidence for living organisms at any time in the history of the Moon.

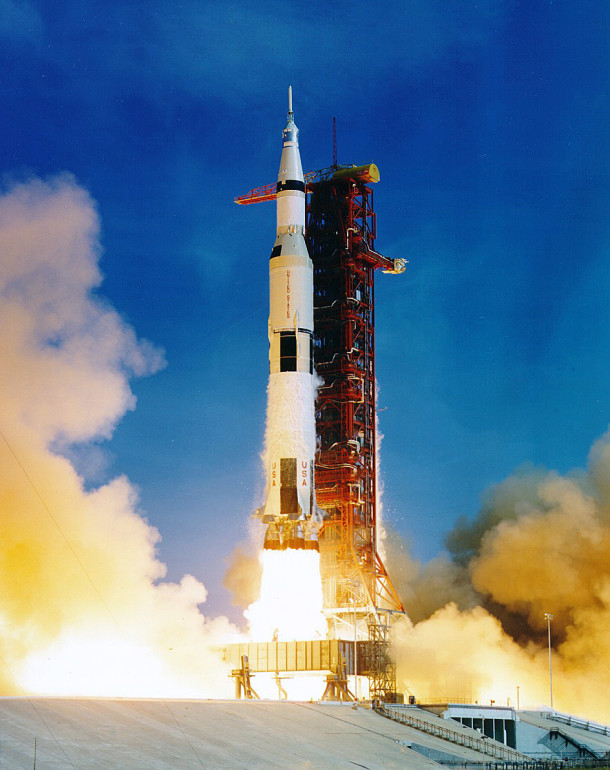

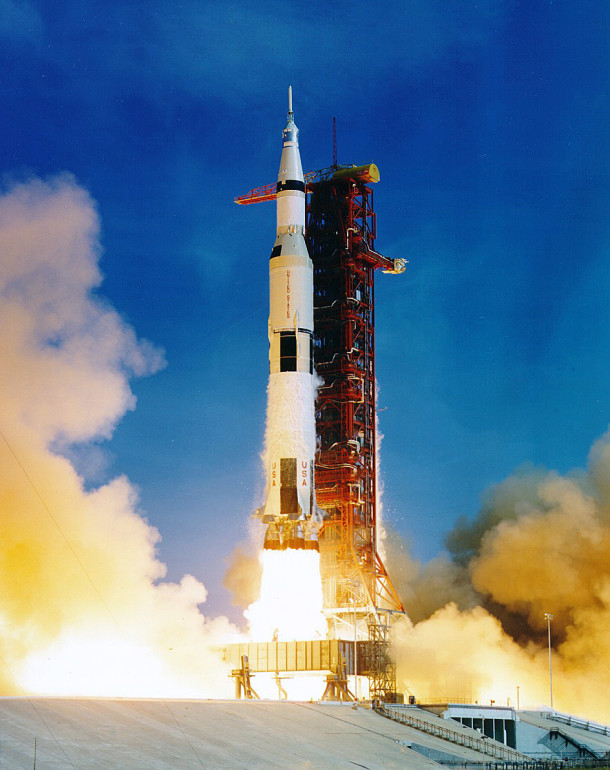

Fifty years ago today, the epic flight of Apollo 11, the first mission to land men on the Moon, began with launch from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at Merritt Island, Florida. Nearly 1-million people gathered around America’s famous space complex to witness the historic event. An estimated 1-billion viewers worldwide watched the proceedings on television.

The names of the Apollo 11 crew are now legend: Mission Commander Neil A. Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins. Each astronaut was making his second spaceflight.

The overall Apollo 11 spacecraft weighed over 100,000 pounds and consisted of 3 major components: Command Module, Service Module, and Lunar Excursion Module (LEM). Out of American history came the names used to distinguish two of these components from one another. The Command Module was named Columbia, the feminine personification of America, while the Lunar Excursion Module received the appellation Eagle in honor of America’s national bird.

The Apollo-Saturn V launch stack measured 363-feet in length, had a maximum diameter of 33-feet, and weighed 6.7-milllion pounds at ignition of its five F-1 engines. The vehicle rose from the Earth on 7.7-million pounds of lift-off thrust.

The acoustic energy produced by the Saturn’s first stage propulsion system was unlike anything in common experience. The sound produced was like intense, continuous thunder even miles away from the launch point. Ground and structure shook disturbingly and a person’s lungs vibrated within their chest cavity.

Lift-off of Apollo 11 (AS-506) from KSC’s LC-39A occurred at 13:32 UTC on Wednesday, 16 July 1969. The target for the day’s launch, the Moon, was 218,096 miles distant from Earth. It took 12 seconds just for the massive Apollo 11 launch vehicle to clear the launch tower. However, a scant 12 minutes later, the Apollo 11 spacecraft was safely in low earth orbit (LEO) traveling at 17,500 miles per hour.

Following checkout in earth orbit, trans-lunar injection, and earth-to-moon coast, Apollo 11 entered lunar orbit nearly 76 hours after lift-off. Now, the big question: Would they make it? Even Apollo 11’s Command Module Pilot, Michael Collins, estimated that the chance of a successful lunar landing on the first attempt was only 50/50. The answer would soon come. History’s first lunar landing attempt was now only 24 hours away.

Fifty-eight years ago this month, Mercury Seven Astronaut Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Jr. became the second American to go into space. Grissom’s suborbital mission was flown aboard a Mercury space capsule that he named Liberty Bell 7.

The United States first manned space mission was flown on Friday, 05 May 1961. On that day, NASA Astronaut Alan B. Shepard, Jr. flew a 15-minute suborbital mission down the Eastern Test Range in his Freedom 7 Mercury spacecraft. Known as Mercury-Redstone 3, Shepard’s mission was entirely successful and served to ignite the American public’s interest in manned spaceflight.

Shepard was boosted into space via a single stage Redstone rocket. This vehicle was originally designed as an Intermediate-Range ballistic Missile (IRBM) by the United States Army. It was man-rated (that is, made safer and more reliable) by NASA for the Mercury suborbital mission. A descendant of the German V-2 missile, the Redstone produced 78,000 lbs of sea level thrust.

Shepard’s suborbital trajectory resulted in an apogee of 101 nautical miles (nm). With a burnout velocity of 7,541 ft/sec, Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 263 nm downrange of its LC-5 launch site at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Shepard endured a maximum deceleration of 11 g’s during the reentry phase of the flight.

Mercury-Redstone 4 was intended as a second and confirming test of the Mercury spacecraft’s space-worthiness. If successful, this mission would clear the way for pursuit and achievement of the Mercury Program’s true goal which was Earth-orbital flight. All of this rested on the shoulders of Gus Grissom as he prepared to be blasted into space.

Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft was a better ship than Shepard’s steed from several standpoints. Liberty Bell 7 was configured with a large centerline window rather than the two small viewing ports featured on Freedom 7. The vehicle’s manual flight controls included a new rate stabilization system. Grissom’s spacecraft also incorporated a new explosive hatch that made for easier release of this key piece of hardware.

Mercury-Redstone 4 (MR-4) was launched from LC-5 at Cape Canaveral on Friday, 21 July 1961. Lift-off time was 12:20:36 UTC. From a trajectory standpoint, Grissom’s flight was virtually the same as Shepard’s. He found the manual 3-axis flight controls to be rather sluggish. Spacecraft control was much improved when the new rate stabilization system was switched-on. The time for retro-fire came quickly. Grissom invoked the retro-fire sequence and Liberty Bell 7 headed back to Earth.

Liberty Bell 7’s reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere was conducted in a successful manner. The drogue came out at 21,000 feet to stabilize the spacecraft. Main parachute deployed occurred at 12,300 feet. With a touchdown velocity of 28 ft/sec, Grissom’s spacecraft splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 32 seconds after lift-off. America now had both a second spaceman and a second successful space mission under its belt.

Following splashdown, Grissom logged final switch settings in the spacecraft, stowed equipment and prepared for recovery as several Marine helicopters hovered nearby. As he did so, the craft’s new explosive hatch suddenly blew for no apparent reason. Water started to fill the cockpit and the surprised astronaut exited the spacecraft as quickly as possible.

Grissom found himself outside his spacecraft and in the water. He was horrified to see that Liberty Bell 7 was in imminent peril of sinking. The primary helicopter made a valiant effort to hoist the spacecraft out of the water, but the load was too much for it. Faced with losing his vehicle and crew, the pilot elected to release Liberty Bell 7 and abandon it to a watery grave.

Meanwhile, Grissom struggled just to stay afloat in the churning ocean. The prop blast from the recovery helicopters made the going even tougher. Finally, Grissom was able to retrieve and get himself into a recovery sling provided by one of the helicopters. He was hoisted aboard and subsequently delivered safely to the USS Randolph.

In the aftermath of Mercury-Redstone 4, accusations swirled around Grissom that he had either intentionally or accidentally hit the detonation plunger that activated the explosive hatch. Always the experts on everything, especially those things which they have little comprehension of, the denizens of the press insinuated that Grissom must have panicked. Grissom steadfastly asserted to the day that he passed from this earthly scene that he did no such thing.

Liberty Bell 7 rested at a depth of 15,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean until it was recovered by a private enterprise on Tuesday, 20 July 1999; a day short of the 38th anniversary of Gus Grissom’s MR-4 flight. The beneficiary of a major restoration effort, Liberty Bell 7 is now on display at the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center. The spacecraft’s explosive hatch was never found.

As for Gus Grissom, ultimate vindication of his character and competence came in the form of his being named by NASA as Commander for the first flights of Gemini and Apollo. Indeed, Grissom and rookie astronaut John W. Young successfully made the first manned Gemini flight in March of 1965 during Gemini-Titan 3. Later, Grissom, Edward H. White II and Roger B. Chaffee trained as the crew of Apollo 1 which was slated to fly in early 1967. Their lives were tragically cut short as a result of the infamous AS-204 (Apollo 1) Spacecraft Fire of Friday, 27 January 1967.

Fifty-seven years ago this month, USAF Major Robert M. White flew the North American X-15 hypersonic research aircraft to a record altitude of 314,750 feet (51.8 nautical miles). In doing so, he became the first X-15 pilot to be awarded USAF Astronaut Wings.

The North American X-15 was the first manned hypersonic aircraft. It was designed, engineered, constructed and first flown in the 1950′s. As originally conceived, the X-15 was designed to reach 4,000 mph (Mach 6) and 250,000 feet. Before its flight test career was over, the type would meet and exceed both performance goals.

North American built a trio of X-15 airframes; Ship No. 1 (S/N 56-6670), Ship No. 2 (56-6671) and Ship No. 3 (56-6672). The X-15 measured 50 feet in length, had a wing span of 22 feet and a GTOW of 33,000 lbs. Ship No. 2 would later be modified to the X-15A-2 enhanced performance configuration. The X-15A-2 had a length of 52.5 feet and a GTOW of around 56,000 lbs.

The Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine powered the X-15. Small, but mighty, the XLR-99 generated 57,000 pounds of sea level thrust at full-throttle. It weighed only 910 pounds. The XLR-99 used anhydrous ammonia and LOX as propellants. Burn time varied between 83 seconds for the stock X-15 and about 150 seconds for the X-15A-2.

The X-15 was carried to drop conditions (typically Mach 0.8 at 42,000 feet) by a B-52 mothership. A pair of aircraft were used for this purpose; a B-52A (S/N 52-003) and a B-52B (S/N 52-008). Once dropped from the mothership, the X-15 pilot lit the XLR-99 to accelerate the aircraft. The X-15A-2 also carried a pair of drop tanks which provided propellants for a longer burn time than was possible with the stock X-15 flight.

The X-15 employed both aerodynamic and reaction flight controls. The latter were required to maintain vehicle attitude in space-equivalent flight. The X-15 pilot wore a full-pressure suit in consequence of the aircraft’s extreme altitude capability. The typical X-15 drop-to-landing flight duration was on the order of 10 minutes. All X-15 landings were performed dead-stick.

On Tuesday, 17 July 1962, Bob White flew his 15th X-15 mission. The X-15 and White had already become the first aircraft-pilot duo to hit Mach 4, 5 and 6. On this particular day, White was at the controls of X-15 Ship No. 3. It was the 62nd flight research mission of the X-15 Program with a target maximum altitude of 282,000 feet.

At 09:31:10 UTC, X-15 Ship No. 3 was launched from the B-52B mothership commanded by USAF Captain Jack Allavie. White lit the XLR-99 and pulled into a steep climb. His hypersonic steed rapidly gained altitude. Burnout of the XLR-99 occurred 82 seconds after ignition; 2.0 seconds longer than planned. At this point, White was traveling at 3,832 mph or Mach 5.45. Following an uneventful climb to apogee and a expertly-flown reentry, White touched-down safely on Rogers Dry Lake at 09:41:30 UTC. His reaction to the entire experience was succinctly expressed when he exclaimed, “Boy, that was a ride!”

The extra impulse provided by the longer-than-planned burn of the XLR-99 rocket engine drove White’s X-15 more than 32,000 feet higher than planned. The resulting apogee of 314,750 feet established a still-standing FAI world altitude record for piloted aircraft. The occasion also marked the first time that the X-15 flew higher than 300,000 feet. For flying beyond 50 statute miles (264,000 feet), Bob White received USAF Astronaut Wings; the first X-15 pilot to be awarded such.

Bob White piloted the X-15 a total of sixteen (16) times. He was one (1) of only twelve (12) men to fly the aircraft. White left X-15 Program and Edwards AFB in 1963. He went on to serve his country in numerous capacities as a member of the Air Force including flying 70 combat missions in Viet Nam. He returned to Edwards AFB as AFFTC Commander in August of 1970.

Major General Robert M. White retired from the United States Air Force in 1981. During his period of military service, he received numerous decorations and awards including the Air Force Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star with three oak leaf clusters, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters, Bronze Star Medal, and Air Medal with 16 oak leaf clusters.

Bob White was a true American hero. He was one of those heroes who neither sought nor received much notoreity for his accomplishments. He served his country and the aviation profession well. Bob White’s final flight occurred on Wednesday, 17 March 2010. He was 85 years of age.

Sixty-two years ago this week, USAF Major William F. “Pete” Knight made an emergency landing in X-15 No. 1 at Mud Lake, Nevada. Knight somehow managed to save the hypersonic aircraft following a complete loss of electrical power as the vehicle passed through 107,000 feet during the climb.

The famed X-15 Program conducted 199 flights between June 1959 and October 1968. North American Aviation (NAA) built three (3) X-15 aircraft. Twelve (12) men from NAA, USAF and NASA flew the X-15. Eight (8) pilots received astronaut wings for flying the X-15 beyond 250,000 feet. One (1) aircraft and one (1) pilot were lost during flight test.

The X-15 flew as fast as 4,520 mph (Mach 6.7) and as high as 354,200 feet. The basic airframe measured 50 feet in length, featured a wing span of 22 feet and had a gross weight of 33,000 pounds. The type’s Reaction Motors XLR-99 rocket engine burned anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen to produce a sea level thrust of 57,000 pounds. The X-15 used both 3-axis aerodynamic and ballistic flight controls.

An X-15 mission was fast-paced. Flight time from B-52 drop to unpowered landing was typically 10 to 12 minutes in duration. The pilot wore a full pressure suit and experienced 6 to 7 G’s during pull-out from max altitude. There really was no such thing as a routine X-15 mission. However, all X-15 missions had one factor in common; high danger.

On Thursday, 29 June 1967, X-15 No. 1 (S/N 56-6670) made its 73rd and the X-15 Program’s 184th free flight. Launch took place at 1828 UTC as the NASA B-52B launch aircraft (S/N 52-0008) flew at Mach 0.82 and 40,000 feet near Smith Ranch, Nevada. Knight, making his 10th X-15 flight, quickly ignited the XLR-99 and started the climb upstairs.

The X-15 was performing well and Knight was enjoying the flight until 67.6 seconds into a planned 87 second XLR-99 burn. That’s when the engine suddenly quit. A couple of heartbeats later, the Stability Augmentation System (SAS) failed, the Auxiliary Power Units (APU’s) ceased operating, the X-15’s generators stopped functioning and the cockpit lights went out. This was the total hit; a complete power failure.

Pete Knight was now just along for the ride. No thrust to power the aircraft. No electrical power to run onboard systems. No hydraulics to move flight controls. Even the reaction controls appeared inoperative. The X-15 continued upward, but it wallowed aimlessly in the low dynamic pressure of high altitude flight. At this point, Knight considered taking his chances and punching-out.

The X-15 went over the top at 173,000 feet. On the way downhill, Knight was able to get some electrical power from the emergency battery. This meant that he now had some hydraulic power and could utilize the X-15’s flight control surfaces. Knight next tried to fire-up the APU’s. The right APU would not respond. The left APU fired, but the its generator would not engage.

As the X-15 descended and the dynamic pressure built-up, Knight was able to maneuver his stricken X-15. He headed for Mud Lake in a sustained 6-G turn. As he leveled off at 45,000 feet, Knight instinctively knew he could now make the east shore of the Nevada dry lake. But it was tough work to fly the X-15. Knight ended-up using both hands to fly the airplane; one hand on the side stick and one hand on the center stick.

While Knight was trying to get his airplane down on the ground in one piece, only he and his Maker knew his whereabouts. The X-15 flight test team certainly didn’t, since Knight’s radio, telemetry and radar transponder were now inop. Further, the X-15 was not being skinned tracked at the time of the electrical anomaly. Just before he touched-down at Mud Lake, Knight’s X-15 was spotted by NASA’s Bill Dana who was flying a F-104N chase aircraft.

Pete Knight made a good landing at Mud Lake. The X-15 slid to a stop. After a struggle with the release mechanism, he managed to get the canopy open. Hot and soaked with perspiration, Knight somehow removed his own helmet. A ground crewman usually did that for him. But there were no flight support people at his X-15 landing site on this day.

As he attempted to get out of the X-15 cockpit, Knight pulled an emergency release. To his surprise, the headrest blew off, bounced off the canopy and smacked him square in the head. Undeterred, Knight got out of the cockpit and onto terra firma. In the meantime, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules had landed at Mud Lake. Wearily, Pete Knight got onboard and returned to Edwards Air Force Base.

Post-flight investigation revealed that the most probable source of the X-15’s electrical failure was arcing in a flight experiment system. This system had been connected to the X-15’s primary electrical bus. The solution was to connect flight experiments to the secondary electrical bus.

Reflecting on Knight’s amazing recovery from almost certain disaster, long-time NASA flight test manager Paul Bickle claimed the fete was among the most impressive of the X-15 Program. Indeed, it was Pete Knight’s clearly uncommon piloting skill and poise under pressure that gave him the edge.