Fifty years ago this month, the crew of Apollo 13 departed Earth and headed for the Fra Mauro highlands of the Moon. Less than six days later, they would be back on Earth following an epic life and death struggle to survive the effects of an explosion that rocked their spacecraft 200,000 miles from home.

Apollo 13 was slated as the 3rd lunar landing mission of the Apollo Program. The intended landing site was the mountainous Fra Mauro region near the lunar equator. The Apollo 13 crew consisted of Commander James A. Lovell, Jr., Lunar Module Pilot Fred W. Haise, Jr. and Command Module Pilot John L. (Jack) Swigert, Jr. Lovell was making his fourth spaceflight (second to the Moon) while Haise and Swigert were space rookies.

Apollo 13 lifted-off from LC-39A at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Saturday, 11 April 1970. The official launch time was 19:13:00 UTC (13:13 CST). During second stage burn, the center engine shutdown two minutes early as a result of excessive longitudinal structural vibrations. The outer four J-2 engines burned 34 seconds longer to compensate. Arriving safely in low Earth orbit, Lovell observed that every mission seemed to have at least one major glitch. Clearly, Apollo 13′s was now out of the way!

The Apollo 13 payload stack consisted of a Command Module (CM), Service Module (SM) and Lunar Module (LM). The entire ensemble had a lift-off mass of nearly 49 tons. In keeping with tradition, the Apollo 13 crew gave call signs to their Command Module and Lunar Modules. This helped flight controllers distinguish one vehicle from the other over the communications net during mission operations. The CM was named Odyssey and the LM was given the name of Aquarius.

The first two days of the outward journey to the Moon were uneventful. In fact, some at Mission Control in Houston, Texas seemed somewhat bored. The same could be said for the ever-astute press corps who predictably reported that Americans were now responding to the lunar landing missions with a collective yawn. The journalistic sages averred that the space program needed some pepping-up. Going to the Moon might have been impossible yesterday, but today its just run-of-the-mill stuff. Actually, it was all kind of easy. So wrote they of the fickle Fourth Estate.

It all started with a bang at 03:07:53 UTC on Tuesday, 14 April 1970 (21:07:53 CST, 13 April 1970) with Apollo 13 distanced 200,000 miles from Earth. “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” This terse statement from Jack Swigert informed Mission Control that something ominous had just occurred onboard Apollo 13. Jim Lovell reported that the problem was a “Main B Bus undervolt”. A potentially serious electrical system problem.

But what was the exact nature of the of problem and why did it occur? Nary a soul in the spacecraft nor in Mission Control could provide the answers. All anyone really knew at the moment was that two of three fuel cells formerly supplying electricity to the Command Module were now dead. Arguably more alarming, Oxygen Tank No. 2 was empty with Tank No. 1 losing oxygen at a high rate.

There was something else. The Apollo 13 reaction control system was firing in apparent response to some perturbing influence. But what was it? The answer came with all the subtlety of a sledge hammer blow. Jim Lovell reported that some kind of gas was venting from the spacecraft into space. That chilling observation suddenly explained why the No. 1 oxygen tank was losing pressure so rapidly.

Once Mission Control and the Apollo 13 astronauts fully comprehended the gravity of the situation, the entire team went to work to bring the spacecraft home. Odyssey was powered-down to conserve its battery power for reentry while Aquarius was powered-up and became a makeshift lifeboat. A major problem was that Aquarius had battery power and water sufficient for only 40 hours of flight. The trip home would take 90 hours.

Amazingly, engineering teams at Mission Control conceived and tested means to minimize electrical usage onboard Aquarius. However, the Apollo 13 crew would have to endure privation and hardships to survive. The cabin temperature in Aquarius got down to 38F and each man was permitted only six ounces of water per day. The walls of the spacecraft were covered with condensation. Sleep was almost impossible and fatigue became another relentless enemy to survival.

And then there was the build-up of carbon dioxide. The LM environmental system (EV) was designed to support two men. Now there were three. Between the CM and LM, there was an ample supply of lithium hydroxide canisters to scrub the gas from the cabin atmosphere for the trip home. However, the square CM canisters were incompatible with the circular openings on LM EV. The engineers on the ground invented a device to eliminate this compatibility using materials found onboard the spacecraft.

The Apollo 13 crew had to fire the LM descent motor several times in order to adjust their return trajectory. Use of the SM propulsion system to effect these firings was denied the crew due to concerns that the explosion could have damaged it. These rocket motor firings required precise inertial navigation. The star sightings required for celestial navigation were impossible to make owing to the huge cloud of debris surrounding the spacecraft. Means were devised to use the Sun as the primary navigational source.

While the nation and indeed the world looked on, the miracle of Apollo 13 slowly unfolded. Many a humble heart uttered a prayer for and in behalf of the trio of astronauts. Millions throughout the world followed the men’s journey home via newspaper, radio, television and other media.

As Apollo 13 approached the Earth, the overriding issue was whether the systems onboard Odyssey could be successfully brought back on line. The walls and instrument panels of the craft were drenched with condensation. Unquestionably, the electronics and wiring bundles behind those instrument panels were also soaking wet. Would they short-out once electrical energy flowed through them again? Would there be enough battery power for reentry?

Happily, the CM power-up sequence was successfully accomplished. Once again the resourceful engineers at Mission Control produced under extreme duress. They devised an intricate and never-attempted-in-flight power-up sequence for the CM. Too, the extra insulation added to the CM’s electrical system in the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire provided protection from condensation-induced electrical arcing.

Approximately four hours prior to reentry, the Apollo 13 crew jettisoned the SM. What they saw was shocking. The module was missing a complete external panel and most of the equipment inside was gone or significantly damaged. One hour prior to entry, Aquarius, their trusty space lifeboat, was also jettisoned. The only concern now was whether the Command Module base heat shield had survived the explosion intact.

On Friday, 17 April 1970, Odyssey hit entry interface (400,000 feet) at 36,000 feet per second. Other than a worrisome additional 33 seconds of plasma-induced communications blackout (4 minutes, 33 seconds total), the reentry was entirely nominal. Splashdown occurred at 18:07:41 UTC near American Samoa in the Pacific Ocean. The USS Iwo Jima quickly recovered spacecraft and crew.

The post-flight mishap investigation revealed that Oxygen Tank No. 2, located deep within the bowels of the SM, exploded when the crew conducted a cryo stir of its multi-phase contents. Unknown to all was the fact that a mismatch between the tank heater and thermostat had resulted in the Teflon insulation of the internal wiring being severely damaged during previous ground operations. This meant that the tank was now a bomb and would detonate its contents when used the next time. In this case, the next time was in flight. The warning signs were there, but went unheeded.

Apollo 13 never landed at Fra Mauro. And none of its crew would ever again fly in space. But in many ways, Apollo 13 was NASA’s finest hour. Overcoming myriad seemingly intractable obstacles in the aftermath of a completely unanticipated catastrophe, deep in trans-lunar space, will forever rank high among the legendary accomplishments of spaceflight. With essentially no margin for error and in the harsh glare of public scrutiny, NASA wrested victory from the tentacles of almost certain failure and brought three weary men safely back to their home planet.

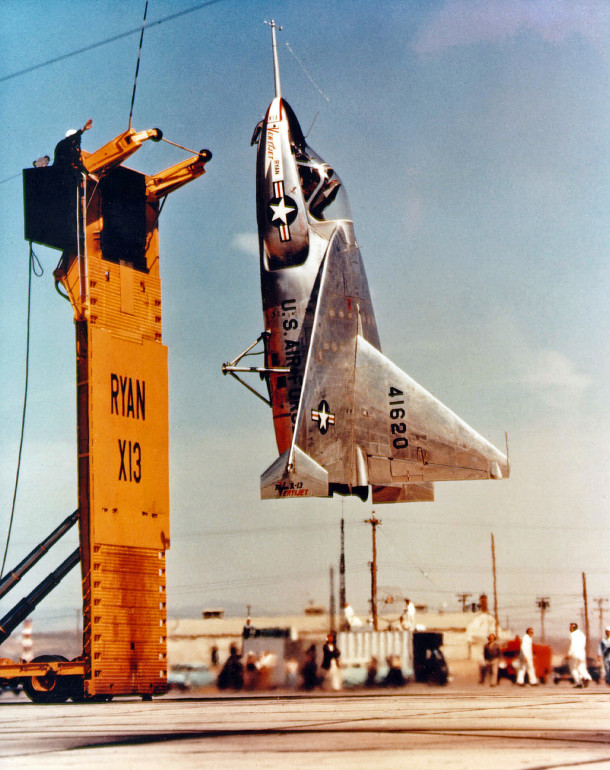

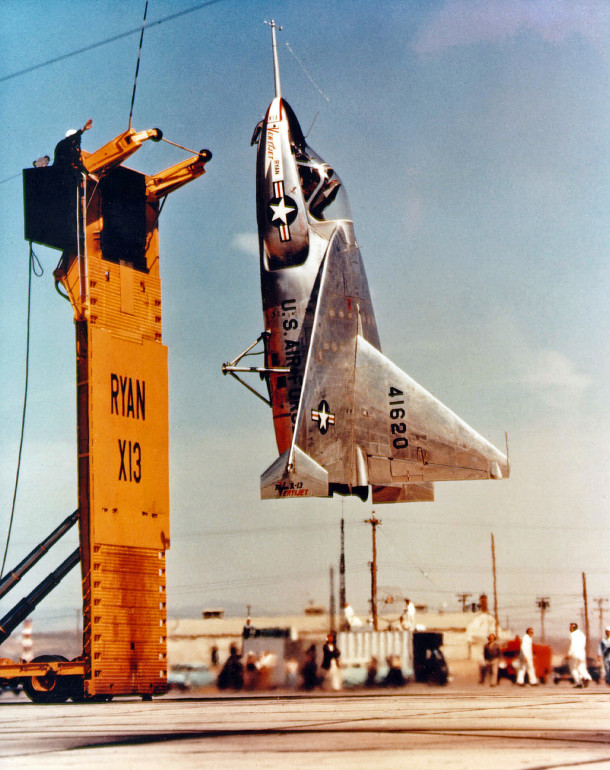

Sixty-three years ago this month, the USAF/Ryan X-13 Vertijet completed history’s first vertical-to horizontal-back to vertical flight of a jet-powered Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) aircraft. This event took place at Edwards Air Force Base, California with Ryan Chief Test Pilot Peter F. Girard at the controls.

The X-13 Vertijet was an experimental flight vehicle designed to determine the feasibility of a jet-powered Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) aircraft. The initial idea for the type dates back to 1947 when the United States Navy (USN) put Ryan under contract to explore the viability of a jet-powered VTOL aircraft. At the time, the Navy was quite interested in exploiting the VTOL concept for tactical advantage. The service envisioned basing VTOL aircraft on submarines and small surface ships.

The USN-Ryan team worked the X-13 VTOL concept for over six (6) years to good effect. While no flight vehicle took to the skies during that time, a great deal of progress was made in the realm of hovering flight using ground-based vertical test rigs. Particular effort was focused on VTOL low-speed flight controls. However, Navy research and development funding was slashed in the aftermath of the Korean War and the X-13 project ran out of money in the summer of 1953.

Fortunately, the United States Air Force (USAF) had become interested in the X-13 and the possibilities of VTOL flight prior to the Navy running out of money. The junior service assumed ownership of the X-13 effort after securing the funding required to continue the program. A pair of X-13 prototypes were subsequently built and flown by Ryan Aeronautical. These aircraft were assigned USAF serial numbers 54-1619 and 54-1620, respectively.

The X-13 measured 23.5 feet in length and had a wing span of 21 feet. The single-place aircraft featured a maximum take-off weight of approximately 7,300 pounds. Hovering flight control was provided via wing tip-mounted yaw and roll nozzles. The heart of the VTOL aircraft was its reliable Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet. The non-afterburning powerplant used standard JP-4 fuel and produced a maximum thrust of 10,000 pounds.

The X-13 was transported, launched and retrieved using a special flatbed trailer. Hinged at one end, the trailer was raised and lowered through the instrumentality of a pair of hydraulic rams. Once raised to a vertical position, the X-13 hung on its nose hook from a steel suspension cable stretched between two mechanical arms. Rather than landing gear, the aircraft sat on two non-retractable tubular bumpers positioned on the lower fuselage.

Flight testing of the No. 1 X-13 (S/N 54-1619) began on Saturday, 10 December 1955 at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The purpose of this initial flight was to test the X-13’s conventional flight characteristics. The aircraft was configured with tricycle landing to permit a runway take-off. Ryan Chief Test Pilot Peter F. “Pete” Girard flew a brief seven minute test hop in which he determined that the X-13 had serious control issues in all 3-axes. The subsequent installation of yaw and roll dampers fixed the problem.

The next phase of flight testing involved vertical hovering flight wherein aircraft handling and control characteristics were explored. For doing so, the X-13 was outfitted with a vertical landing gear system composed of a tubular support structure and a quartet of small caster-type wheels. Thus configured, the X-13 could take-off, hover and land in the vertical. As vertical flight testing progresed, important refinements were made to the aircraft’s turbojet throttling and reaction control systems.

The first vertical flight test was made on Monday, 28 May 1956 with the No. 1 aircraft. Pete Girard was again in the cockpit. Restricting maximum altitude to about 50 feet above ground level, Girard found the aircraft relatively easy to fly and land. Succeeding flight tests would ultimately include practice hook landings wherein a 1-inch thick manila rope suspended between a pair of 50-foot towers was engaged. A great deal of experience with and confidence in the X-13 system was accrued during these tests.

Prior to flying the X-13 all-up mission, an additional phase of flight testing was required which would culminate with the events of Monday, 28 November 1956. With the conventional landing gear installed on the No. 1 aircraft, Girard took-off from Edwards and climbed to 6,000 feet. He then slowly pitched the aircraft into the vertical and hovered for an extended period. Girard then executed a transition back to horizontal flight and landed. The first-ever horizontal-to vertical-back to horizontal flight transition was entirely successful.

The big day came on Thursday, 11 April 1957. Edwards Air Force Base again served as the test site. This time using the No. 2 X-13 (S/N 54-1620), Pete Girard took-off vertically, ascended in hovering flight and transitioned to conventional flight. Following a series of standard flight maneuvers, Girard transitioned the aircraft back into a vertical hover, descended and engaged the suspension cable on the support trailer with the aircraft’s nose hook. The first-ever vertical-to horizontal-back to vertical flight of a jet-propelled VTOL aircraft was history.

Both X-13 aircraft would go on to successfully conduct additional flight testing and stage numerous flight demonstrations during the remainder of 1957. However, innovative and impressive as it was, the X-13 did not garner the advocacy and backing required to proceed to production. A combination of bad timing, a risk averse military and combat performance limitations resulted in the aircraft and its technology quickly fading from the aviation scene.

Remarkably, both X-13 aircraft survived the type’s flight test program. The No. 1 aircraft (S/N 54-1619) is displayed at the San Diego Aerospace Museum in San Diego, California. The No. 2 X-13 aircraft (S/N 54-1620) is on display in the Research and Development Gallery of the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Sixty-one years ago this week, NASA held a press conference in Washington, D.C. to introduce the seven men selected to be Project Mercury Astronauts. They would become known as the Mercury Seven or Original Seven.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight program. The overall objective of Project Mercury was to place a manned spacecraft in Earth orbit and bring both man and machine safely home. Project Mercury ran from 1959 to 1963.

The men who would ultimately become Mercury Astronauts were among a group of 508 military test pilots originally considered by NASA for the new role of astronaut. The group of 508 candidates was then successively pared to 110, then 69 and finally to 32. These 32 volunteers were then subjected to exhaustive medical and psychological testing.

A total of 18 men were still under consideration for the astronaut role at the conclusion of the demanding test period. Now came the hard part for NASA. Each of the 18 finalists was truly outstanding and would be a worthy finalist. But there were only 7 spots on the team.

On Thursday, 09 April 1959, NASA publicly introduced the Mercury Seven in a special press conference held for this purpose at the Dolley Madison House in Washington, D.C. The men introduced to the Nation that day will forever hold the distinction of being the first official group of American astronauts. In the order in which they flew, the Mercury Seven were:

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr., United States Navy. Shepard flew the first Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-3) on Friday, 05 May 1961. He was also the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. Shepherd did so as Commander of Apollo 14 (AS-509) in February 1971. Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia on 21 July 1998 at the age of 74.

Vigil Ivan Grissom, United States Air Force. Grissom flew the second Mercury sub-orbital mission (MR-4) on Friday, 21 July 1961. He was also Commander of the first Gemini mission (GT-3) in March 1965. Gus Grissom might very well have been the first man to walk on the Moon. But he died in the Apollo 1 Fire, along with Astronauts Edward H. White II and Roger Chaffee, on Friday, 27 January 1967. Gus Grissom was 40 at the time of his death.

John Herschel Glenn Jr., United States Marines. Glenn was the first American to orbit the Earth (MA-6) on Thursday, 22 February 1962. He was also the only Mercury Astronaut to fly a Space Shuttle mission. He did so as a member of the STS-95 crew in October of 1998. Glenn was 77 at the time and still holds the distinction of being the oldest person to fly in space. John Glenn was the last member of the Mercury Seven to depart this earth when he passed away in December 2016 at the age of 95.

Seventy-seven years ago this month, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most intriguing and haunting stories in the annals of aviation. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.

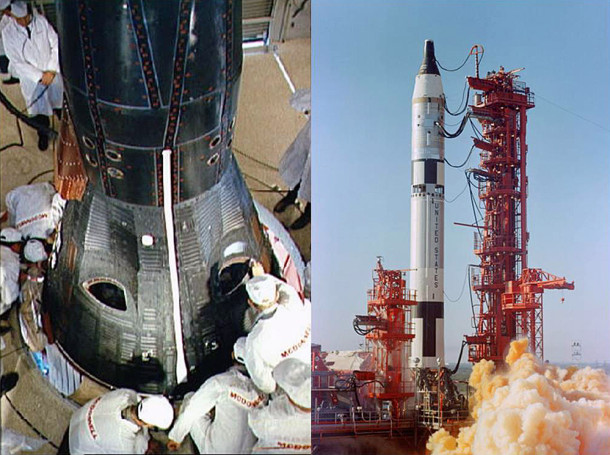

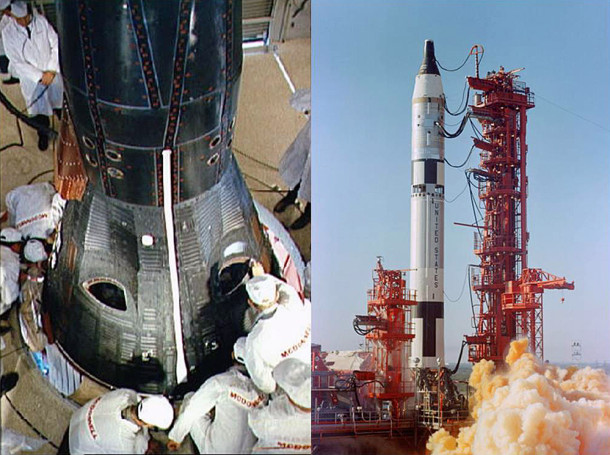

Fifty-five years ago this week, Gemini III was launched into Earth orbit with astronauts Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom and John W. Young onboard. The 3-orbit mission marked the first time that the United States flew a multi-man spacecraft.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight series. Project Apollo would ultimately land men on the Moon and return them safely to the Earth. In between these historic spaceflight efforts would be Project Gemini.

The purpose of Project Gemini was to develop and flight-prove a myriad of technologies required to get to the Moon. Those technologies included spacecraft power systems, rendezvous and docking, orbital maneuvering, long duration spaceflight and extravehicular activity.

The Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the de-boost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbit attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

Gemini-Titan III (GT-3) lifted-off at 14:24 UTC from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Tuesday, 23 March 1965. The two-stage Titan II launch vehicle placed Gemini 3 into a 121 nautical mile x 87 nautical mile elliptical orbit.

Gemini 3’s primary objective was to put the maneuverable Gemini spacecraft through its paces. While in orbit, Grissom and Young fired thrusters to change the shape of their orbital flight path, shift their orbital plane, and dip down to a lower altitude. Gemini 3 was also the first time that a manned spacecraft used aerodynamic lift to change its entry flight path.

As spacecraft commander, Gus Grissom named his cosmic chariot The Molly Brown in reference to a then-popular Broadway show; “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”. Grissom chose the moniker in memory of his first spaceflight experience wherein his Liberty Bell 7 Mercury spacecraft sunk in almost 17,000 feet of water during post-splashdown operations.

At almost two (2) hours into the mission, pilot John Young presented Grissom with his favorite sandwich which had been smuggled onboard. Grissom and Young took a bite of the corned beef sandwich and put it away since loose crumbs could get into spacecraft electronics with catastrophic results. Not amused, NASA management reprimanded the crew after the mission.

Gemini 3 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 19:16:31 UTC following a 3 orbit mission. The spacecraft landed 45 nautical miles short of the intended splashdown point due to a mis-prediction of aerodynamic lift. Although hot and sea-sick, Commander Grissom refused to open the spacecraft hatches until the recovery ship USS Intrepid came on station.

Nine (9) additional Gemini space missions would follow the flight of Gemini 3. Indeed, the historical record shows that the Gemini Program would fly an average of every two (2) months by the time Gemini XII landed in December 1966. During that period, the United States would take the lead in the race to the Moon that it would never relinquish.

Sixteen years ago this week, the NASA X-43A scramjet-powered flight research vehicle reached a record speed of over 4,600 mph (Mach 6.83). The test marked the first time in the annals of aviation that a flight-scale scramjet accelerated an aircraft in the hypersonic Mach number regime.

NASA initiated a technology demonstration program known as HYPER-X in 1996. The fundamental goal of the HYPER-X Program was to successfully demonstrate sustained supersonic combustion and thrust production of a flight-scale scramjet propulsion system at speeds up to Mach 10. The term scramjet stands for Supersonic Combustion RAMJET.

The scramjet is a key to sustained hypersonic flight within the earth’s atmosphere. Whereas rockets are capable of producing large thrust magnitudes, both the duration of operation and the amount of thrust per unit propellant mass is low. In part, this is because a rocket has to carry its own fuel and oxidizer supplies. A scramjet is a much more efficient producer of thrust in that it only has to carry its fuel and uses the atmosphere as its oxidizer source.

Rocket technology is a highly developed discipline with a deep experience and application base. In contradistinction, flight-scale scramjet technology is still in a developmental stage. Considerations such as initiating and sustaining stable combustion is a supersonic stream, efficient conversion of fuel chemical energy to kinetic energy, and optimal integration of the scramjet propulsion system into a hypersonic airframe are among the challenges that face designers.

Also known as the HYPER-X Research Vehicle (HXRV), the X-43A aircraft was a scramjet test bed. The aircraft measured 12 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and weighed nearly 3,000 pounds. The X-43A was boosted to scramjet take-over speeds with a modified Orbital Sciences Pegasus rocket booster.

The combined HXRV-Pegasus stack was referred to as the HYPER-X Launch Vehicle (HXLV). Measuring approximately 50 feet in length, the HXLV weighed slightly more than 41,000 pounds. The HXLV was air-launched from a B-52 mothership. Together, the entire assemblage constituted a 3-stage vehicle.

The second flight of the HYPER-X program took place on Saturday, 27 March 2004. The flight originated from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Using Runway 04, NASA’s venerable B-52B (S/N 52-0008) started its take-off roll at approximately 20:40 UTC. The aircraft then headed for the Pacific Ocean launch point located just west of San Nicholas Island.

At 21:59:58 UTC, the HXLV fell away from the B-52B mothership. Following a 5 second free fall, rocket motor ignition occurred and the HXLV initiated a pull-up to start its climb and acceleration to the test window. It took the HXLV about 90 seconds to reach a speed of slightly over Mach 7.

Following rocket motor burnout and a brief coast period, the HXRV (X-43A) successfully separated from the Pegasus booster at 94,069feet and Mach 6.95. The HXRV scramjet was operative by Mach 6.83. Supersonic combustion and thrust production were successfully achieved. Total power-on flight duration was approximately 11 seconds.

As the X-43A decelerated along its post-burn descent flight path, the aircraft performed a series of data gathering flight maneuvers. A vast quantity of high-quality aerodynamic and flight control system data were acquired for Mach numbers ranging from hypersonic to transonic. Finally, the X-43A impacted the Pacific Ocean at a point about 450 nautical miles due west of its launch location. Total flight time was approximately 15 minutes.

The HYPER-X Program made history that day in late March 2004. Supersonic combustion and thrust production of an airframe-integrated scramjet were achieved for the first time in flight; a goal that dated back to before the X-15 Program. Along the way, the X-43A established a speed record for airbreathing aircraft and earned a Guinness World Record for its efforts.

Sixty-four years ago this month, the lone remaining USAF/Martin XB-51 light attack bomber prototype crashed during take-off from El Paso International Airport in Texas. The cause of the mishap was attributed to premature rotation of the aircraft leading to an unrecoverable stall.

A product of the post-WWII 1940’s, the Martin XB-51 was envisioned as a jet-powered replacement for the piston-driven Douglas A-26 Invader. The swept-wing XB-51 utilized a unique propulsion system which consisted of a trio of General Electric J47 turbojets. Demonstrated top speed was 560 knots at sea level.

The XB-51 was a good-sized airplane. With a length of 85 feet and a wing span of 53 feet, the XB-51 had a nominal take-off weight of around 56,000 lbs. The wings were swept 35 degrees aft and incorporated 6 degrees of anhedral. The latter feature to counter the large dihedral effect produced by the type’s tee-tail.

A pair of XB-51 aircraft were built by Martin for USAF. Ship No. 1 (S/N 46-0685) first took to the air in October of 1949 followed by the flight debut of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) in April of 1950. The air crew consisted of a pilot who sat underneath a large, clear canopy and a navigator housed within the fuselage.

While the XB-51 flew hundreds of hours in flight test and made many lasting contributions to the aviation field, the aircraft never went into production. This fate was primarily the result of having lost a head-to-head competitive fly-off against the English Electric Canberra B-57A light attack bomber in 1951.

The No. 1 XB-51 aircraft was lost on Sunday, 25 March 1956 during take-off from El Paso International Airport. The mishap aircraft accelerated more slowly than normal and with the end of the runway coming up quickly, the pilot rotated the aircraft in a attempt to get airborne. Unfortunately, the rotation was premature and the wing stalled. The aircraft exploded on impact and the crew of USAF Major James O. Rudolph and Staff-Sargent Wilbur R. Savage were killed.

The loss of the No. 1 XB-51 was preceded by the destruction of Ship No. 2 (S/N 46-0686) on Friday, 09 May 1952. That tragedy occurred during low-altitude aerobatic maneuvers at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The pilot, USAF Major Neil H. Lathrop, perished in the resulting post-impact explosion and inferno.

As a footnote, the XB-51 was never assigned an official nickname by the Air Force. However, it was unofficially referred to in some aviation circles as the Panther. Due to its prominently-long fuselage, the less majestic monicker of “Flying Cigar” was sometimes used as well.

Sixty-five years ago today, North American test pilot George F. Smith became the first man to survive a high dynamic pressure ejection from an aircraft in supersonic flight. Smith ejected from his F-100A Super Sabre at 777 MPH (Mach 1.05) as the crippled aircraft passed through 6,500 feet in a near-vertical dive.

On the morning of Saturday, 26 February 1955, North American Aviation (NAA) test pilot George F. Smith stopped by the company’s plant at Los Angeles International Airport to submit some test reports. Returning to his car, he was abruptly hailed by the company dispatcher. A brand-new F-100A Super Sabre needed to be test flown prior to its delivery to the Air Force. Would Mr. Smith mind doing the honors?

Replying in the affirmative, Smith quickly donned a company flight suit over his street clothes, got the rest of his flight gear and pre-flighted the F-100A Super Sabre (S/N 53-1659). After strapping into the big jet, Smith went through the normal sequence of aircraft pre-launch flight control and system checks. While the control column did seem a bit stiff in pitch, Smith nonetheless decided that his aerial steed was ready for flight.

Smith executed a full afterburner take-off to the west. The fleet Super Sabre eagerly took to the air. Accelerating and climbing, the aircraft was almost supersonic as it passed through 35,000 feet. Peaking out around 37,000 feet, Smith sensed a heaviness in the flight control column. Something wasn’t quite right. The jet was decidedly nose heavy. Smith countered by pulling aft stick.

The Super Sabre did not respond at all to Smith’s control inputs. Instead, it continued an un-commanded dive. Shallow at first, the dive steepened even as the 215-lb pilot pulled back on the stick with all of his might. But all to no avail. The jet’s hydraulic system had failed. As the stricken aircraft now accelerated toward the ground, Smith rightly concluded that this was going to be a short ride.

George Smith knew that he had only one alternative now; Eject. However, he also knew that the chances were quite small that he would survive what was quickly shaping-up to be a quasi-supersonic ejection. Suddenly, over the radio, Smith heard another Super Sabre pilot flying in his vicinity frantically yell: “Bail out, George!” So exhorted, the test pilot complied.

Smith jettisoned his canopy. The roar from the air-stream around him was unlike anything he had ever heard. Almost paralyzed with fear, Smith reflexively hunkered-down in the cockpit. The exact wrong thing to do. His head needed to be positioned up against the seat’s headrest and his feet placed within retraining stirrups prior to ejection. But there was no time for any of that now. Smith pulled the ejection seat trigger.

George Smith’s last recollection of his nightmare ride was that the Mach Meter read 1.05; 777 mph at the ejection altitude of 6,500 feet above the Pacific Ocean. These flight conditions corresponded to a dynamic pressure of 1,240 pounds per square foot. As he was fired out of the cockpit and into the harsh air-stream, Smith’s body was subjected to an astounding drag force of around 8,000 lbs producing on the order of 40-g’s of deceleration.

Mercifully, Smith did not recall what came next. The ferocious wind blast stripped him of his helmet, oxygen mask, footwear, flight gloves, wrist watch and even his ring. Blood was forced into his head which became grotesquely swollen and his facial features unrecognizable. His eyelids fluttered and his eyes were tortuously mauled by the aerodynamic and inertial load of his ejection. Smith’s internal organs, most especially his liver, were severely damaged. His body was horribly bruised and beaten as it flailed end-over-over end uncontrollably.

Smith and his seat parted company as programmed followed by automatic deployment of his parachute. The opening forces were so high that a third of the parachute material was ripped away. Thankfully, the remaining portion held together and the unconscious Smith landed about 75 yards away from a fishing vessel positioned about a half-mile form shore. Providentially, the boat’s skipper was a former Navy rescue expert. Within a minute of hitting the water, Smith was rescued and brought onboard.

George Smith was hovering near death when he arrived at the hospital. In severe shock and with only a faint pulse, doctors quickly went to work. Smith awoke on his sixth day of hospitalization. He could hear, but he couldn’t see. His eyes had sustained multiple subconjunctival hemorrhages and the prevailing thought at the time was that he would never see again.

Happily, George Smith did recover almost fully from his supersonic ejection experience. He spent seven (7) months in the hospital and endured several operations. During that time, Smith’s weight dropped to 150 lbs. He was left with a permanently damaged liver to the extent that he could no longer drink alcohol. As for Smith’s vision, it returned to normal. However, his eyes were ever after somewhat glare-sensitive and slow to adapt to darkness.

Not only did George Smith return to good health, he also got back in the cockpit. First, he was cleared to fly low and slow prop-driven aircraft. Ultimately, he got back into jets, including the F-100A Super Sabre. Much was learned about how to markedly improve high speed ejection survivability in the aftermath of Smith’s supersonic nightmare. He in essence paid the price so that others would fare better in such circumstances as he endured.

It is possible that George Smith was not the first pilot to eject supersonically. USN LCdr Authur Ray Hawkins survived ejection from his stricken Grumman F9F-6 Cougar in 1953. Aircraft speed at ejection was never definitively determined, but was estimated to be between 688 (Mach 0.99) and 782 mph (Mach 1.16). In any event, the dynamic pressure and therefore the airloads associated with Hawkins ejection were less than half that of Smith’s punch-out.

George Smith was thirty-one (31) at the time of his F-100A mishap. He lived a happy and productive thirty-nine (39) more years after its occurrence. Smith passed from this earthly scene in 1994.

Fifty years ago this month, a USAF F-106A Delta Dart (S/N 58-0787) out of Malmstrom AFB, Montana made a wheels-up landing in a farmer’s field despite the fact that there was no pilot onboard. The pilot, Lieutenant Gary Foust, had ejected earlier when he was unable to recover the aircraft from a flat spin. This incident became known in popular culture as “The Cornfield Bomber”.

On Monday, 02 February 1970, a trio of pilots from the 71st Fighter Interceptor Squadron (FIS) took-off from Malmstrom AFB, Montana for the purpose of practicing air combat maneuvers. A fourth pilot had intended to be part of this group but was forced to abort the mission when his aircraft’s drag parachute strangely deployed on the ramp.

The pilots who took to the air that day were Major Thomas Curtis, Major James Lowe, and Faust. Each man was at the controls of a Convair F-106A Delta Dart; aka “The Ultimate Interceptor”. The three-ship formation departed Malmstrom for an area roughly 90 miles north of the base designated for the flying of air combat maneuvers and engagements.

The practice session began with a two-on-one head-on engagement. Approaching the other two aircraft at Mach 1.90 in full afterburner, Captain Curtis pulled his aircraft into the vertical. His intent was to induce the other pilots to follow him upstairs. They did so. In passing through 38,000 feet, he executed a vertical rolling scissors maneuver. However, Curtis had superior energy at the pull-up point. Thus, neither Lowe nor Foust could gain a tactical advantage in the fight. When Curtis executed a high-g rudder reversal, Foust attempted to stay with him. That’s when things deteriorated rapidly for Foust.

Foust flew his F-106A into an accelerated stall around 35,000 feet as he attempted to maintain position with Curtis. That is, his aircraft exceeded the stall angle-of-attack while simultaneously losing speed due to the motion-retarding effects of gravity and drag due to lift. The F-106A fell off into a series of post-stall gyrations followed by entry into a flat spin. The flat spin is a high angle-of-attack, deep stall condition from whence recovery was typically not possible in a Delta Dart.

Notwithstanding the futility of the task, Foust diligently applied anti-spin procedures in textbook fashion. However, the aircraft continued to fall in a flat spin. In desperation, Foust deployed his drag chute hoping that it would act as an anti-spin device. Unfortunately, the chute became totally useless for that purpose when it wrapped itself around the vertical tail of his falling steed. Running out of altitude and time, Foust had no other recourse but to abandon his airplane. He did so somewhere around 12,000 feet.

Foust was rocketed out of his Delta Dart and got a good chute. He landed in the Bear Paw Mountains, and fortunately was brought to safety by local citizens on snowmobiles. However, to the utter amazement of Foust, Curtis, and Lowe, the abandoned delta-winged aircraft snapped out of its flat spin and began to glide. Apparently, the equal and opposite reaction of the aircraft to the force produced by the rocket-powered ejection seat forced the nose of the airplane below the stall angle-of-attack. Thus, the wing began to produce lift again. Further, as part of his anti-spin procedures, Foust had configured the controls of the Delta Dart in take-off trim and brought the throttle to idle.

The net state of affairs now was that the F-106A became a pretty good glider. Gliding at about 175 knots, it ultimately made a wheels-up landing in a farmer’s snow-covered field near Big Sandy, Montana. The landing was aided by ground effect which enhanced the lift on the airplane as the vehicle neared the ground. Incredibly, the wings remained level throughout the landing slide-out. Further, late in the landing, the F-106A magically turned 20 degrees from its touchdown azimuth and avoided running into a pile of rockets directly in its path. In doing so, the airplane slipped through an opening in a fence around the farmer’s property and came to a stop.

When authorities approached the Delta Dart, they found that its canopy was gone, its ejection seat was gone, and so was its pilot. A look into the cockpit revealed that the radar scope was still sweeping for targets. And, although in idle, the still running turbojet produced a bit of thrust. Thus, periodically, the vehicle would lurch forward when the restraining snow around the it melted. Almost two hours later, the turbojet finally stopped running when the aircraft fuel supply ran out.

Remarkably, the pilotless Delta Dart sustained little damage despite the wheels-up landing. The aircraft was later trucked out of the area and sent to McClellan AFB in California for repairs. It ultimately was returned to service with the 71st FIS. Later, it entered the inventory of the 49th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Grifffiss AFB, New York. Fittingly, a measure of closure was accorded (then) Major Gary Foust when he flew this same aircraft again in 1979. Today, USAF F-106A Delta Dart, S/N 58-0787 sits on display for posterity at the USAF National Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

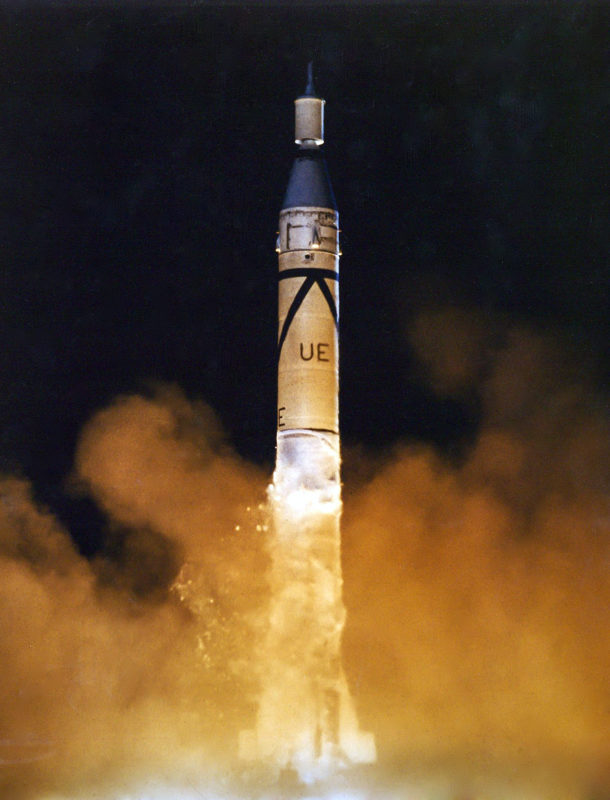

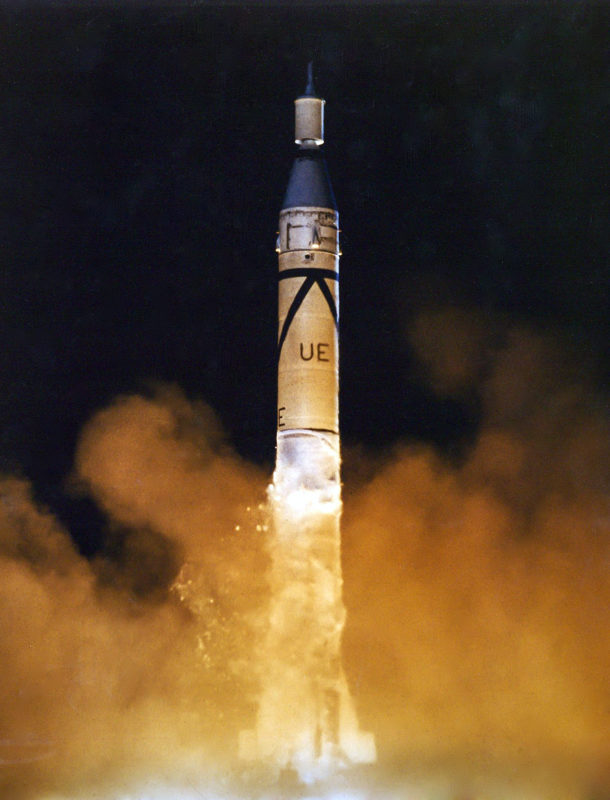

Sixty-two years ago to the day, the United States successfully orbited the country’s first space satellite. Known as Explorer I, the artificial moon went on to discover the Van Allen Radiation Belts, the extensive system of charged particles trapped in the magnetosphere that surrounds the Earth.

The Explorer I satellite was designed and fabricated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) under the direction of Dr. William J. Pickering. The satellite’s instrumentation unit measured 37.25 inches in length, 6.5 inches in diameter, and had a mass of only 18.3 lbs. With its burned-out fourth stage solid rocket motor attached, the total on-orbit mass of the pencil-like satellite was 30.8 lbs.

Explorer I was launched aboard a Jupiter-C (aka Juno I) launch vehicle from LC-26 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Friday, 31 January 1958. Lift-off at occurred at 22:48 EST (0348 UTC). With all four stages performing as planned, Explorer I was inserted into a highly elliptical orbit having an apogee of 1,385 nm and a perigee of 196 nm.

Arguably the most historic achievement of the Explorer I mission was the discovery of a system of charged particles or plasma within the magnetosphere of the Earth. These belts extend from an altitude of roughly 540 to 32,400 nm above mean sea level. Most of the plasma that forms these belts originates from the solar wind and cosmic rays. The radiation levels within the Van Allen Radiation Belts (named in honor of the University of Iowa’s Dr. James A. Van Allen) are such that spacecraft electronics and astronaut crews must be shielded from the adverse effects thereof.

Explorer I operational life was limited by on-board battery life and lasted a mere 111 days. However, it soldiered-on in orbit until reentering the Earth’s atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on Tuesday, 31 March 1970. During the 147 months it spent in space, Explorer I orbited the Earth more than 58,000 times. Data obtained and transmitted by the satellite contributed markedly to mankind’s understanding of the Earth’s space environment.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of Explorer I was that it was the first satellite orbited by the United States. Unknown to most today, this accomplishment was absolutely vital to America’s security, and indeed that of the free world, at the time. The Soviet Union had been first in space with the orbiting of the much larger Sputnik I and II satellites in late 1957. However, Explorer I showed that America also had the capability to orbit a satellite. History records that this capability would quickly grow and ultimately lead to the country’s preeminence in space.