Fifty-eight years ago this month, the USN/Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III interceptor prototype took off on its maiden test flight at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Vought chief test pilot John W. Konrad was at the controls of the advanced high performance aircraft.

The Vought XF8U-3 was designed to intercept and defeat adversary aircraft. Although it bore a close external resemblance to its F8U-1 and F8U-2 forbears, the XF8U-3 was much more than just a block improvement in the Crusader line. It was considerably bigger, faster, and more capable than previous Crusaders and was in reality a new airplane.

The XF8U-3 measured 58.67 feet in length and had a wing span of an inch less than 40 feet. Gross Take-Off and empty weights tipped the scales at 38,770 lbs and 21,860 lbs, respectively. Power was provided by a single Pratt and Whitney J75-P-5A generating 29,500 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner.

A distinctive feature of the XF8U-3 was a pair of ventrally-mounted vertical tails. These surfaces were installed to improve aircraft directional stability at high Mach number. Retracted for take-off and landing, the surfaces were deployed once the aircraft was in flight.

The No. 1 XF8U-3 (S/N 146340) first flew on Monday, 02 June 1958 at Edwards Air Force, California. Vought chief test pilot John W. Konrad did the first flight piloting honors. The aircraft flew well with no major discrepancies reported. Approach and landing back at Edwards were uneventful.

Subsequent flight testing verified that the XF8U-3 was indeed a hot airplane. The type reached a top speed of Mach 2.39 and could have flown faster had its canopy had been designed for higher temperatures. The flight test-determined absolute altitude of 65 KFT was exceeded by 25 KFT in a zoom climb.

Those who flew the XF8U-3 said that the aircraft was a real thrill to fly. The Crusader III displayed outstanding acceleration, maneuverability and high-speed flight stability. Control harmony in pitch, yaw, and roll was extremely good as well.

Despite its great promise, the XF8U-3 never proceeded to production. This was primarily the result of coming up short in a head-to-head competition with the McDonnell F4H-1 Phantom II during the second half of 1958. While the Crusader was faster and more maneuverable than the Phantom, the latter’s mission capability and payload capacity were better.

Most historical records indicate that a total of five (5) Crusader III airframes were built. The serial numbers assigned by the Navy were 146340, 146341, 147085, 147086, and 147087. None of these aircraft exist today.

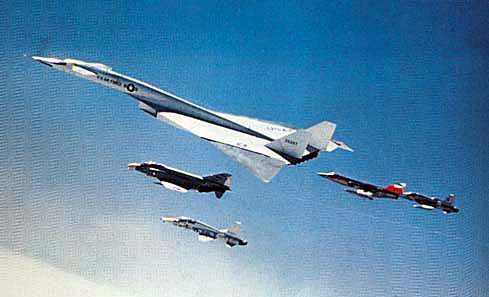

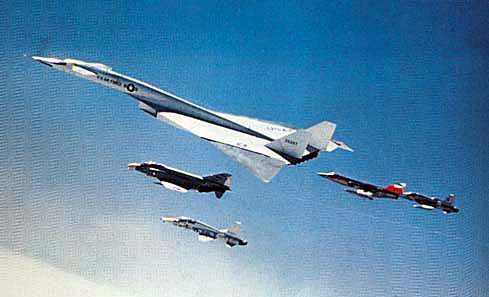

Forty-eight years ago this month, XB-70A Valkyrie Air Vehicle No. 2 (62-0207) took-off from Edwards Air Force Base, California for the final time.

The crew for this flight included aircraft commander and North American test pilot Alvin S. White and right-seater USAF Major Carl S. Cross. White would be making flight No. 67 in the XB-70A while Cross was making his first. For both men, this would be their final XB-70A flight.

In the past several months, Air Vehicle No. 2 had set speed (Mach 3.08) and altitude (74,000 feet) records for the type. But on this fateful Wednesday, 08 June 1966, the mission was a simple one; some run-of-the-mill flight research test points and a multi-aircraft formation photo shoot.

The General Electric Company, manufacturer of the massive XB-70A’s YJ93-GE-3 turbojets, had received permission from Edwards USAF officials to photograph the XB-70A in close formation with a quartet of other aircraft powered by GE engines. The resulting photos were intended to be used for publicity.

The formation, consisting of the XB-70A, a T-38A (59-1601), an F-4B (BuNo 150993), an F-104N (N813NA), and an F-5A (59-4898), was in position at 25,000 feet by 0845. The photographers for this event, flying in a GE-powered Gates Learjet (N175FS) stationed about 600 feet to the left and slightly aft of the multi-ship formation, began taking photos.

The photo session was planned to last 30 minutes, but went 10 minutes longer to 0925. Then at 0926, just as the formation aircraft were starting to leave the scene, the frantic cry of Midair! Midair Midair! came over the communications network.

Somehow, the NASA F-104N, piloted by NASA Chief Test Pilot Joe Walker, had collided with the right wing-tip of the XB-70A. Walker’s out-of-control F-104 then rolled inverted to the left and sheared-off the XB-70A’s twin vertical tails. The F-104N fuselage was severed just behind the cockpit and Walker was killed instantly in the process.

Curiously, the XB-70A continued on in steady, level flight for about 16 seconds despite the loss of its primary directional stability lifting surfaces. Then, as White attempted to control a roll transient, the XB-70A rapidly departed controlled flight.

As the doomed aircraft torturously pitched, yawed and rolled, its left wing structurally failed and fuel spewed furiously from its fuel tanks. White was somehow able to eject and survive. Cross never left the aircraft and rode it down to impact just north of Barstow, California.

A mishap investigation followed and (as always) blame was assigned. However, none of that changed the facts that on this, the Blackest Day at Edwards, American aviation lost two of its best men and aircraft in a flight mishap that never should have happened.

Ten years ago this month, Scaled Composite’s SpaceShipOne flew to an altitude of 62.214 statute miles. The flight marked the first time that a privately-developed flight vehicle had flown above the 62-statute mile boundary that entitles the flight crew to FAI-certified astronaut wings. As a result, SpaceShipOne pilot Mike Melvill became history’s first private citizen astronaut.

SpaceShipOne Mission 15P began with departure from California’s Mojave Spaceport at 0647 PDT. Carrying SpaceShipOne at the centerline station, Scaled’s White Knight aircraft climbed to the drop altitude of 47,000 feet.

At 0750 PDT on Monday, 21 June 2004, the 7,900-pound SpaceShipOne fell away from the White Knight and Melvill immediately ignited the 16,650-pound thrust hybrid rocket motor. Melvill quickly then pulled SpaceShipOne into a vertical climb.

Passing through 60,000 feet, SpaceShipOne experienced a series of uncommanded rolls as it encountered a wind shear. Melvill struggled with the controls in an attempt to arrest the roll transient. Then, late in the boost, the vehicle lost primary pitch trim control. In response, Melvill switched to the back-up system as he continued the ascent.

Rocket motor burnout occurred at 180,000 feet with SpaceShipOne traveling at 2,150 mph. It now only weighed 2,600 pounds. The vehicle then coasted to an apogee of 62.214 statute miles (328,490 feet). The target maximum altitude was 68.182 statute miles (360,000 feet). However, the control problems encountered going upstairs caused the trajectory to veer somewhat from the vertical.

Melvill experienced approximately 3.5 minutes of zero-g flight going over the top. He had some fun during this period as he released a bunch of M&M’s and watched the chocolate candy pieces float in the SpaceShipOne cabin.

Back to business now, Melvill transitioned SpaceShipOne to the high-drag feathered configuration in preparation for the critical entry phase of the mission. The vehicle initially accelerated to over 2,100 mph in the airless void before encountering the sensible atmosphere. At one point during atmospheric entry, Melvill experienced in excess of 5 g’s deceleration.

At 57,000 feet, Melvill reconfigured SpaceShipOne back to the standard aircraft configuration for powerless flight back to the Mojave Spaceport. Fortunately, the aircraft was a very good glider. The control problems encountered during the ascent resulted in atmospheric entry taking place 22 statute miles south of the targeted reentry point.

SpaceShipOne touched-down on Mojave Runway 12/30 at 0814 PDT; thus ending an historic, if not harrowing mission.

After the flight, Mike Melvill had much to say. But perhaps the following quote says it best for the rest of us who can only imagine what it was like: “And it was really an awesome sight, I mean it was like nothing I’ve ever seen before. And it blew me away, it really did. … You really do feel like you can reach out and touch the face of God, believe me.”

Fifty-seven years ago this month, the USAF/Convair XB-58A supersonic bomber exceeded twice the speed of sound for the first time. Convair test pilot Beryl A. Erickson was at the controls of the famed delta-winged beauty.

The B-58A Hustler was the United States first supersonic-capable bomber and was originally designed for the strategic mission. The aircraft was powered by four (4) General Electric J79-GE-5A turbojets generating 62,400 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner. Maximum take-off weight was nearly 177,000 lbs.

Convair’s stunning delta-winged bomber was 97 feet in length with a wing span of 57 feet. Wing area was roughly 1,550 square feet. Aircraft maximum height was 30 feet as measured from the ground to the top of the vertical tail.

Flight crew for the B-58A consisted of the pilot, bombadier/navigator, and defensive systems operator. The crew was arranged in tandem with each crew member seated in a separate cockpit. The type carried thermonuclear ordnance. A total of 116 B-58A aircraft were manufactured.

The B-58A performance was impressive then and now. It had a maximum speed of 1,400 mph and a service ceiling of 63,400 feet. The aircraft could climb in excess of 17,000 feet per minute at gross take-off weight and up to 46,000 feet per minute near minimum weight.

On Saturday, 29 June 1957, USAF/Convair XB-58A (S/N 55-660) first attained its double-sonic design airspeed when it flew to Mach 2.03 at an altitude of 43,250 feet. This historic achievement took place on the type’s 24th flight. Mission total elapsed time was 1 hour and 55 minutes.

The Hustler had a difficult gestation due to its advanced design and demanding performance requirements. A number of aircraft and flight crews were lost due to a variety of baffling flight control and structural problems. First flight took place on 11 November 1956 with the type finally entering service on 15 March 1960.

The USAF/Convair B-58A Hustler was operational for just 10 years and was retired from the USAF inventory on 31 January 1970. The aircraft was never used in anger.

Fifty-three years ago this week, President John F. Kennedy boldly proposed that the United States conduct a manned lunar landing before the end of the 1960’s. The President’s clarion call to glory was delivered during a special session of the United States Congress which focused on “urgent national needs”.

The transcript of that historic speech given on Friday, 25 May 1962 indicates that the ninth and last issue addressed by President Kennedy was simply entitled SPACE. The most stirring words of that portion of his speech may well be these:

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Although he did not live to see the fulfillment of that goal, history shows that 8 years, 1 month, and 26 days later, the United States of America did indeed land a man (men) on the moon and returned him (them) safely to earth before the decade was out.

Thus, as a country, we can say now, even as we said then to our departed leader: Mission Accomplished, Mr. President.

Forty-one years ago this month, astronauts Pete Conrad, Joe Kerwin and Paul Weitz became the first NASA crew to fly aboard the recently-orbited Skylab space station. Not only would the crew establish a new record for duration in earth orbit, they would effect critical repairs to the space station which had been seriously damaged during launch.

Skylab was America’s first space station. The program followed closely on the heels of the historic Apollo lunar landing effort. Skylab provided the United States with a unique space platform for obtaining vast quantities of scientific data about the Earth and the Sun. It also served as a means for ascertaining the effects of long-duration spaceflight on human beings.

A Saturn IVB third stage served as Skylab’s core. This huge cylinder, which measured 48-feet in length and 22-feet diameter, was modified for human occupancy and was known as the Orbital Workshop (OWS). With the addition of a Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA) and Airlock Module (AM), Skylab had a total length of 83-feet.

Skylab was also outfitted with a powerful space observatory known as the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). This unit sat astride the MDA and was configured with a quartet of electricity-producing solar panels. The OWS had a pair of solar panels as well. The entire Skylab stack weighed 85 tons.

The Skylab space station (Skylab 1) was placed into a 270-mile orbit using a Saturn V launch vehicle on Monday, 14 May 1973. Upon reaching orbit, it quickly became apparent that all was far from well aboard the space station. The micro-meteoroid shield and solar panel on one side of the OWS had been lost during ascent. The other OWS solar panel was stuck and did not deploy as planned.

With the loss of an OWS solar panel, Skylab would not have enough electrical energy to conduct its mission. The station was also heating up rapidly (temperatures approached 190 F at one point). The lost micro-meteoroid shield also provided protection from solar heating. Sans this protection, internal temperatures could rise high enough to destroy food, medical supplies, film and other perishables and render the OWS uninhabitable.

NASA engineers quickly went to work developing fixes for Skylab’s problems. A mechanism was invented to free the stuck solar panel. A parasol of gold-plated flexible material, deployed from an OWS scientific airlock, was then fashioned and tested on the ground. This material would cover the exposed portion of the OWS and provide the needed thermal shielding.

The onus was now on the Skylab 2 crew of Conrad, Kerwin and Weitz to implement the requisite fixes in orbit. On Friday, 25 May 1973, the Skylab 2 crew and their Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) were rocketed into orbit by a Saturn IB launch vehicle. They quickly rendezvoused with Skylab and verified its sad condition. It was time to get to work.

The first order of business was to try to free the stuck solar panel. As Conrad flew the CSM in close proximity to Skylab, Kerwin held Weitz by the feet as the latter leaned out of the open CSM hatch and attempted to release the stuck solar panel with a pair of special cutters. No joy in spaceville. The solar panel refused to deploy.

The Skylab 2 crew next attempted to dock with Skylab. They tried six times and failed. The CSM drogue and probe was not functioning properly. The crew had to fix it or go home. With great difficulty, they did so and were finally able to dock with Skylab. The objective now was to enter Skylab and deploy the parasol thermal shield.

With Conrad remaining in the CSM, Kerwin and Weitz sported gas masks and cautiously entered Skylab. The temperature inside of the OWS was 130 F. Fortunately, the air was found to be of good quality and the pair went to work deploying the thermal shield through a scientific airlock. The deployment was successful and the temperature started to slowly fall.

It would not be until Thursday, 07 June 1973 that the stuck solar panel finally would be freed. On that occasion, Conrad and Kerwin donned EVA suits and spent 8 hours working outside of Skylab. Their initial efforts with the cutters were unsuccesful.

Undeterred, Conrad and Kerwin improvised and were able to cut the strap that restrained the solar panel. Then, heaving with all their might, the pair finally freed the solar panel. In obedience to Newton’s 3rd Law, as the solar panel deployed in one direction, the astronauts went flying in the other. Happily, they were able to collect themselves and safely reenter the now adequately-powered Skylab.

Skylab 2 went on to spend 28 days in orbits; a record for the time. This record was quickly eclipsed by the Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 crews which spent 59 and 84 days in space, respectively. Skylab was an unqualified success and provided a plethora of terrestrial, solar and human factors data of immense importance to space science. These data played a vital role in the design and development of the ISS.

Skylab was abandoned following the Skylab 4 mission in February of 1974. The plan was to reactivate it and raise its orbit using the Space Shuttle when the latter became operational. Unfortunately, a combination of a rapidly deteriorating orbit and delays in flying the Shuttle conspired against bringing this plan to fruition. Skylab reentered the Earth’s atmosphere and broke-up near Australia in July of 1979.

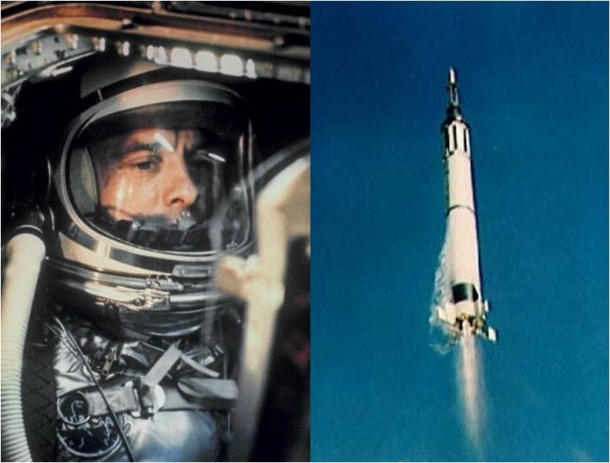

Fifty-one years ago today, NASA Astronaut Leroy Gordon Cooper was successfully launched into Earth orbit to begin a 22-orbit mission lasting 34 hours. Designated Mercury-Atlas No. 9 (MA-9), Cooper’s flight was the final orbital space mission of the fabled Mercury Program.

Cooper’s eventful space mission began with lift-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-14 at 13:04 hours UTC on Wednesday, 15 May 1963. Splashdown of his Faith 7 spacecraft occurred 70 miles southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, 16 May 1963. Mission total elapsed time was 34 hours 19-minutes 49-seconds.

While the first 19 orbits of the MA-9 mission were mostly unremarkable, the final three orbits severely tested Cooper’s mettle and piloting skills.

By the time that he manually initiated ripple-firing of the retro motors at the end of the 22nd orbit, Cooper was flying a dead spacecraft. The electrical system was not functioning, the environmental control system was saturated with carbon dioxide, and even the mission clock was inoperative. Temperatures in the spacecraft exceeded 130F.

Cooper had to align his spacecraft for retro-fire using the horizon as a reference, used a watch for timing, and manually operated the reaction control system to counter dangerous spacecraft oscillations during the retro burn.

Cooper also manually controlled Faith 7 during entry and initiated deployment of the drogue and main parachutes.

Incredibly, Cooper landed within 5 miles of the recovery ship USS Kearsarge. In so doing, he established the record for the most accurate landing in the Mercury Program. Gordon Cooper was the last American astronaut to orbit the Earth alone.

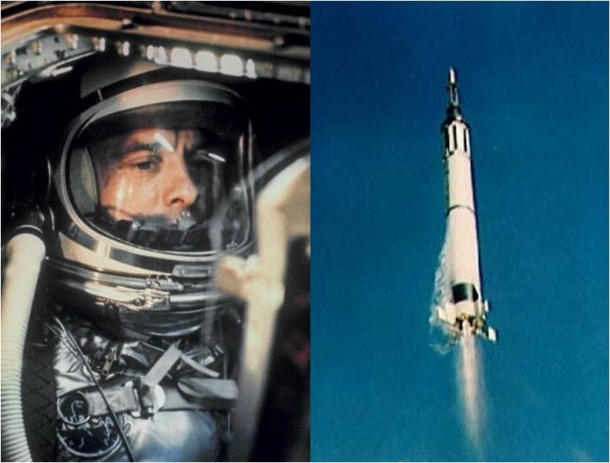

Fifty-three years ago today, United States Navy Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. became the first American to be launched into space. Shepard named his Mercury spacecraft Freedom 7.

Officially designated as Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) by NASA, the mission was America’s first true attempt to put a man into space. MR-3 was a sub-orbital flight. This meant that the spacecraft would travel along an arcing parabolic flight path having a high point of about 115 nautical miles and a total range of roughly 300 nautical miles. Total flight time would be about 15 minutes.

The Mercury spacecraft was designed to accommodate a single crew member. With a length of 9.5 feet and a base diameter of 6.5 feet, the vehicle was less than commodious. The fit was so tight that it would not be inaccurate to say that the astronaut wore the vehicle. Suffice it to say that a claustrophobic would not enjoy a trip into space aboard the spacecraft.

Despite its diminutive size, the 2,500-pound Mercury spacecraft (or capsule as it came to be referred to) was a marvel of aerospace engineering. It had all the systems required of a space-faring craft. Key among these were flight attitude, electrical power, communications, environmental control, reaction control, retro-fire package, and recovery systems.

The Redstone booster was an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) modified for the manned mission. The Redstone’s uprated A-7 rocket engine generated 78,000 pounds of thrust at sea level. Alcohol and liquid oxygen served as propellants. The Mercury-Redstone combination stood 83 feet in length and weighed 66,000 pounds at lift-off.

On Friday, 05 May 1961, MR-3 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 5 at 14:34:13 UTC. Alan Shepard went to work quickly calling out various spacecraft parameters and mission events. The astronaut would experience a maximum acceleration of 6.5 g’s on the ride upstairs.

Nearing apogee, Shepard manually controlled Freedom 7 in all 3 axes. In doing so, he positioned the capsule in the required 34-degree nose-down attitude. Retro-fire occurred ontime and the retro package was jettisoned without incident. Shepard then pitched the spacecraft nose to 14 degrees above the horizon preparatory to reentry.

Reentry forces quickly built-up on the plunge back into the atmosphere with Shepard enduring a maximum deceleration of 11.6 g’s. He had trained for more than 12 g’s prior to flight. At 21,000 feet, a 6-foot droghue chute was deployed followed by the 63-foot main chute at 10,000 feet. Freedom 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean 15 minutes and 28 seconds after lift-off.

Following splashdown, Shepard egressed Freedom 7 and was retreived from the ocean’s surface by a recovery helicopter. Both he and Freedom 7 were safely onboard the carrier USS Lake Champlain within 11 minutes of landing. During his brief flight, Shepard had reached a maximum speed of 5,180 mph, flown as high as 116.5 nautical miles and traveled 302 nautical miles downrange.

The flight of Freedom 7 had much the same effect on the Nation as did Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927. However, in light of the Cold War fight against the world-wide spread of Soviet communism, Shepard’s flight arguably was more important. Indeed, Alan Shepard became the first of what Tom Wolfe called in his classic book The Right Stuff, the American single combat warrior.

For his heroic MR-3 efforts, Alan Shepard was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by an appreciative nation. In February 1971, Alan Shepard walked on the surface of the Moon as Commander of Apollo 14. He was the lone member of the original Mercury Seven astronauts to do so. Shepard was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Freedom in 1978.

Alan Shepard succumbed to leukemia in July of 1998 at the age of 74. In tribute to this American space hero, naval aviator and US Naval Academy graduate, Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 spacecraft now resides in a place of honor at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

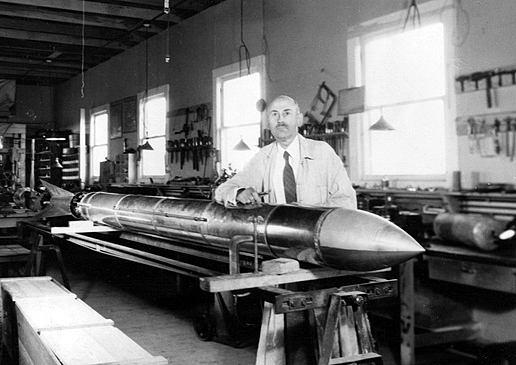

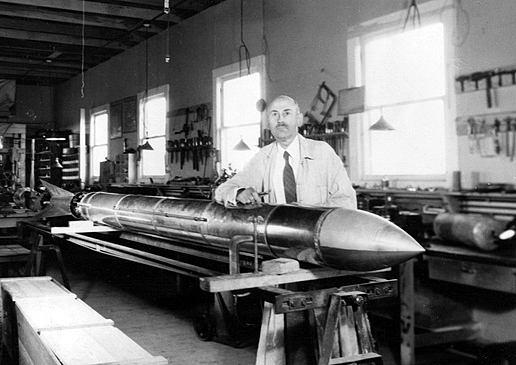

Seventy-nine years ago this month, pioneering rocket scientist Robert H. Goddard and staff fired a liquid-fueled rocket to a record altitude of 7,500 feet above ground level. The record-setting flight took place at Roswell, New Mexico.

Robert Hutchings Goddard was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on Thursday, 05 October 1882. He was enamored with flight, pyrotechnics, rockets and science fiction from an early age. By the time he was 17, Goddard knew that his life’s work would combine all of these interests.

Goddard was a sickly youth, but spent his well moments as a voracious reader of all manner of science-oriented literature. He graduated in 1904 from South High School in Worcester as the valedictorian of his class. He matriculated at Worcester Polytechnic and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in physics in 1908. A Master of Science degree and Ph.D. from Worcester’s Clark University followed in 1910 and 1911, respectively.

Goddard spent the next eight years of his life working on numerous propulsion and rocket-related projects. Then, in 1919, he published his now-famous scientific treatise entitled A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes. In that paper, the press glommed on to Goddard’s passing mention that a multi-staged rocket could conceivably fly all the way to the Moon.

Goddard was roundly ridiculed for his fanciful prognostications about Moon flight. The New York Times was especially derogatory in its estimation of Goddard’s ideas and accused him of junk science. A Times editorial even criticized Goddard for his ”misconception” that a rocket could produce thrust in the vacuum of space.

Even the U.S. government largely ignored Goddard. This scornful treatment to which Goddard was subject hurt him profoundly. So much so that he spent the remainder of his life alienated from the denizens of the press as well as the dolts of governmental employ.

Despite the blow to his professional reputation, Goddard resolutely pressed on with his rocket research. Indeed, after more that five years of intense development effort, Goddard and his staff launched the first liquid-fueled rocket on Tuesday, 16 March 1926 in Auburn, Massachusetts. The flight duration was short (2.5 seconds) and the peak altitude tiny (41 feet), but Goddard proved that liquid rocket propulsion was feasible.

Goddard’s liquid-fueled rocket testing would ultimately lead him from the countryside of New England to the desert of the Great South West. With financial support from Harry Guggenheim and the public backing of Charles Lindbergh, Goddard transfered his testing activities to Roswell, New Mexico in 1930. He would continue liquid-fueled rocket testing there until May 1941.

On Friday, 31 May 1935, experimental rocket flight A-8 took to the air from Goddard’s Roswell, New Mexico test site at 1430 UTC. Roughly 15 feet in length and weighing approximately 90 pounds at lift-off, the 9-inch diameter A-8 achieved a maximum altitude of 7,500 feet (1.23 nautical miles) above the desert floor. Only a flight in March of 1937 would go higher (9,000 feet).

Robert Goddard was ultimately credited with 214 U.S. patents for his rocket development work. Only 83 were awarded in his life time. His far-reaching inventions included rocket nozzle design, regenerativley cooled rocket engines, turbopumps, thrust vector controls, gyroscopic control systems and more.

Goddard died at the age of 62 from throat cancer in Baltimore, Maryland on Friday, 10 August 1945. Many years would pass before the full import of his accomplishments was comprehended. Then, the posthumously-bestowed recognition came in torrents. In 1959, Congress issued a special gold medal in Goddard’s honor. The Goddard Spaceflight Center was so named by NASA in 1959 as well. Many more such bestowals followed.

Perhaps the most meaningful of the recognitions ever accorded Robert Hutchings Goddard occurred 24 years after his passing. It was in connection with the first manned lunar landing in July of 1969. And it was poetic not only in terms of its substance and timing, but more particularly in light of the source from whence the recognition came.

A terse statement in the New York Times corrected a long-standing injustice. It read: “Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Issac Newton in the 17th century, and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vaccum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.”

Seventy-one years ago this month, a USAAF/Consolidated B-24D Liberator and her crew vanished upon return from their first bombing mission over Italy. Known as the Lady Be Good, the hulk of the ill-fated aircraft was found sixteen years later lying deep in the Libyan desert more than 400 miles south of Benghazi.

The disappearance of the Lady Be Good and her young air crew is one of the most intriguing and haunting stories in the annals of aviation. Books and web sites abound which report what is now known about that doomed mission. Our purpose here is to briefly recount the Lady Be Good story.

The B-24D Liberator nicknamed Lady Be Good (S/N 41-24301) and her crew were assigned to the USAAF’s 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force operating out of North Africa. Plane and crew departed Soluch Army Air Field, Libya late in the afternoon of Sunday, 04 April 1943. The target was Naples, Italy some 700 miles distant.

Listed from left to right as they appear in the photo above, the crew who flew the Lady Be Good on the Naples raid were the following air force personnel:

1st Lt. William J. Hatton, pilot — Whitestone, New York

2nd Lt. Robert F. Toner, co-pilot — North Attleborough, Massachusetts

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, navigator — Lee’s Summit, Missouri

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, bombardier — Cleveland, Ohio

T/Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger, flight engineer — Saginaw, Michigan

T/Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, radio operator — Lake Linden, Michigan

S/Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, gunner — New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

S/Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, gunner — New Boston, Ohio

S/Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, gunner — Eureka, Illinois

The LBG was part of the second wave of twenty-five B-24 bombers assigned to the Naples raid. Things went sour right from the start as the aircraft took-off in a blinding sandstorm and became separated from the main bomber formation. Left with little recourse, the LBG flew alone to the target.

The Naples raid was less than successful and like most of the other aircraft that did make it to Italy, the LBG ultimately jettisoned her unused bomb load into the Mediterranean. The return flight to Libya was at night with no moon. All aircraft recovered safely with the exception of the Lady Be Good.

It appears that the LBG flew along the correct return heading back towards their Soluch air base. However, the crew failed to recognize when they were over the air field and continued deep into the Libyan desert for about 2 hours. Running low on fuel, pilot Hatton ordered his crew to jump into the dark night.

Thinking that they were still over water, the crewmen were surprised when they landed in sandy desert terrain. All survived the harrowing experience with the exception of bombardier Woravka who died on impact when his parachute failed. Amazingly, the LBG glided to a wings level landing 16 miles from the bailout point.

What happens next is a tale of tragic, but heroic proportions. Thinking that they were not far from Soluch, the eight surviving crewmen attempted to walk out of the desert. In actuality, they were more than 400 miles from Soluch with some of the most forbidding desert on the face of the earth between them and home. They never made it back.

The fate of the LBG and her crew would be an unsolved mystery until British oilmen conducting an aerial recon discovered the aircraft resting in the sandy waste on Sunday, 09 November 1958. However, it wasn’t until Tuesday, 26 May 1959 that USAF personnel visited the crash site. The aircraft, equipment, and crew personal effects were found to be remarkably well-preserved.

The saga about locating the remains of the LBG crew is incredible in its own right. Suffice it to say here that the remains of eight of the LBG crew members were recovered by late 1960. Subsequently, they were respectfully laid to rest with full military honors back in the United States. Despite herculean efforts, the body of Vernon Moore has never been found.

A pair of LBG crew members kept personal diaries about their ordeal in the Libyan desert; co-pilot Toner and flight engineer Ripslinger. These diaries make for sober reading as they poignantly document the slow and tortuous death of the LBG crew. To say that they endured appalling conditions is an understatement. The information the diaries contain suggests that all of the crewmen were dead by Tuesday, 13 April 1943.

Although they did not made it out of the desert, the LBG crewmen far exceeded the limits of human endurance as it was understood in the 1940’s. Five of the crew members traveled 78 miles from the parachute landing point before they succumbed to the ravages of heat, cold, dehydration, and starvation. Their remains were found together.

Desperate to secure help for their companions, Moore, Ripslinger and Shelley left the five at the point where they could no longer travel. Incredibly, Ripslinger’s remains were found 26 miles further on. Even more astounding, Shelley’s remains were discovered 37.5 miles from the group. Thus, the total distance that he walked was 115.5 miles from his parachute landing point in the desert.

We honor forever the memory of the Lady Be Good and her valiant crew. However, we humbly note that theirs is but one of the many cruel and ironic tragedies of war. To the LBG crew and the many other souls whose stories will never be told, may God grant them all eternal rest.