Fifty-four years ago this month, a USAF/Convair B-58A Hustler from the 43rd Bomb Wing at Carswell AFB, Texas set a trio of transcontinental speed records in a round trip from Los Angeles to New York and back. This historic feat was accomplished as part of Operation Heat Rise.

The USAF/Convair B-58A Hustler holds the distinction of being the world’s first supersonic bomber. A product of the 1950’s, the delta-winged aircraft measured 96.8 feet in length and had a wing span of 56.8 feet. GTOW stood around 163,000 lbs. Power was provided by a quartet of General Electric 79 turbojets which produced 62,000 lbs of sea level thrust in afterburner.

The Hustler’s performance was impressive then and now. With a maximum speed of 1,325 mph, the aircraft featured a service ceiling of 64,800 feet and a combat radius of 1,520 nm. The Hustler’s mission range could be markedly increased through employment of aerial refueling.

The B-58’s three man air crew sat in tandem in the order of pilot, navigator and Defensive Systems Officer (DSO). Each man occupied a separate flight station which was equipped with an ejection pod for protection during high speed egress.

The Hustler was part of Strategic Air Command (SAC). It’s primary mission was delivery of nuclear weapons. The aircraft served in the air force’s operational inventory for a period of just 10 years years (1960 to 1970). A total of 116 airframes were produced and none were used in anger.

The Hustler’s high speed capability led to the type being used to establish numerous speed records during its operational life. Operation Heat Rise was one such effort. The goal of this project was to establish segmental and overall speed records for a round trip flight between the west and east coasts of the United States.

On Monday , 05 March 1962, the crew of Major Robert G. Sowers (pilot), Captain Robert MacDonald (navigator) and Captain John T. Walton (DSO) departed Carswell AFB, Texas in B-58A S/N 59-2458 known as the Cowtown Hustler. Other than a new wax job, this aircraft was no different than the other Hustler airframes in the USAF supersonic bomber inventory.

After refueling out over the Pacific Ocean, the aircraft started its coast-to-coast speed run at Mach 2 over Los Angeles, California. Incredibly, the critical ground station monitoring the start time did not record passage of the aircraft overhead. Thus, airplane and crew were called back for a restart of the speed record attempt! This meant another trip to the tanker out over the Pacific to top off the Hustler’s fuel tanks prior to the second try.

Once officially underway, the trip from overhead Los Angeles to overhead New York took 2 hours and 58.71 seconds for an average speed of 1,214.65 mph. The aircraft was refueled over Kansas on its way east. Once out over the Atlantic Ocean, the Hustler reversed course and hit the tanker again.

The return trip from overhead New York to overhead Los Angeles was flown in 2 hours, 15 minutes and 50.08 seconds. As on the eastbound leg, the Hustler took on a load of gas over Kansas. The entire round trip required 4 hours, 41 minutes and 14.98 seconds inclusive of refueling. Each of the aforementioned trip times established new performance records.

An interesting aspect of the return leg to Los Angeles was that the Hustler flew faster than the rotational movement of the earth. Thus, the aircraft and its crew arrived in California roughly 41 minutes earlier than the sun!

After landing in Los Angeles, the crew was enthusiastically greeted by members of the air force, the aerospace industry and the media. In recognition of their accomplishments, each man received the USAF Distinguished Flying Cross at the hand of USAF General Thomas S. Power, Chief of Staff.

Finally, for their impressive performance during Operation Heat Rise, crew and aircraft were the recipients of both the 1962 MacKay and Bendix Trophies. This marked the last time that the latter was ever awarded.

Fifty-one years ago this month, Gemini III was launched into Earth orbit with astronauts Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom and John W. Young in the cockpit. The 3-orbit mission marked the first time that the United States flew a multi-man spacecraft.

Project Mercury was America’s first manned spaceflight series. Project Apollo would ultimately land men on the Moon and return them safely to the Earth. In between these historic spaceflight efforts would be Project Gemini.

The purpose of Project Gemini was to develop and flight-prove a myriad of technologies required to get to the Moon. Those technologies included spacecraft power systems, rendezvous and docking, orbital maneuvering, long duration spaceflight and extravehicular activity.

The Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the deboost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbit attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

Gemini-Titan III (GT-3) lifted-off at 14:24 UTC from LC-19 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on Tuesday, 23 March 1965. The two-stage Titan II launch vehicle placed Gemini 3 into a 121 nautical mile x 87 nautical mile elliptical orbit.

Gemini 3’s primary objective was to put the maneuverable Gemini spacecraft through its paces. While in orbit, Grissom and Young fired thrusters to change the shape of their orbital flight path, shift their orbital plane, and dip down to a lower altitude. Gemini 3 was also the first time that a manned spacecraft used aerodynamic lift to change its entry flight path.

As spacecraft commander, Gus Grissom named his cosmic chariot The Molly Brown in reference to a then-popular Broadway show; “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”. Grissom chose the moniker in memory of his first spaceflight experience wherein his Liberty Bell 7 Mercury spacecraft sunk in almost 17,000 feet of water during post-splashdown operations.

At almost two (2) hours into the mission, pilot John Young presented Grissom with his favorite sandwich which had been smuggled onboard. Grissom and Young took a bite of the corned beef sandwich and put it away since loose crumbs could get into spacecraft electronics with catastrophic results. Not amused, NASA management reprimanded the crew after the mission.

Gemini 3 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at 19:16:31 UTC following a 3 orbit mission. The spacecraft landed 45 nautical miles short of the intended splashdown point due to a misprediction of aerodynamic lift. Although hot and sea-sick, Commander Grissom refused to open the spacecraft hatches until the recovery ship USS Intrepid came on station.

Nine (9) additional Gemini space missions would follow the flight of Gemini 3. Indeed, the historical record shows that the Gemini Program would fly an average of every two (2) months by the time Gemini XII landed in December 1966. During that period, the United States would take the lead in the race to the Moon that it would never relinquish.

Forty-seven years ago this week, the Apollo Lunar Module (LM) flew in space with astronauts onboard for the first time during the Apollo 9 earth-orbital mission. This technological achievement was critical to the success of the first lunar landing mission which occurred a little over 4 months later.

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM) was the world’s first true spacecraft in that it was designed to operate in vacuum conditions only. It was the third and final element of the Apollo spacecraft; the first two elements being the Command Module (CM) and the Service Module (LM).

The LM had its own propulsion, life-support and GNC systems. The vehicle weighed about 32,000 lbs on Earth and was used to transport a pair of astronauts from lunar orbit to the lunar surface and back into lunar orbit.

The spacecraft was really a two-stage vehicle; a descent stage and an ascent stage weighing 22,000 lbs and 10,000 lbs on Earth, respectively. The descent stage rocket motor was throttable and produced a maximum thrust of 10,000 lbs while the ascent stage rocket motor was rated at 3,500 lbs of thrust.

On Monday, 03 March 1969, Apollo 9 was rocketed into earth-orbit by the mighty Saturn V launch vehicle. The primary purpose of this mission was to put the first manned LM through its paces preparatory to the first lunar landing attempt.

During the 10-day mission, the crew of Commander James A. McDivitt, CM Pilot David R. Scott and LM Pilot Russell L. “Rusty” Schweickart fully verified all moon landing-specific operational aspects (short of an actual landing) of the LM. Key orbital activities included multiple-firings of both LM rocket motors and several rendezvous and docking exercises in which the LM flew as far away as 113 miles from the CM/SM pair.

By the time the crew splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean on Thursday, 13 March 1969, America had a new operational spacecraft and a fighting chance to land men on the moon and safely return them to Earth by the end of the decade.

Sixty-one years ago this week, North American test pilot George F. Smith became the first man to survive ejection from an aircraft in supersonic flight at high dynamic pressure. Smith ejected from his F-100A Super Sabre at 777 MPH (Mach 1.05) as the crippled aircraft passed through 6,500 feet in a near-vertical dive.

On the morning of Saturday, 26 February 1955, North American Aviation (NAA) test pilot George F. Smith stopped by the company’s plant at Los Angeles International Airport to submit some test reports. Returning to his car, he was abruptly hailed by the company dispatcher. A brand-new F-100A Super Sabre needed to be test flown prior to its delivery to the Air Force. Would Mr. Smith mind doing the honors?

Replying in the affirmative, Smith quickly donned a company flight suit over his street clothes, got the rest of his flight gear and pre-flighted the F-100A Super Sabre (S/N 53-1659). After strapping into the big jet, Smith went through the normal sequence of aircraft pre-launch flight control and system checks. While the control column did seem a bit stiff in pitch, Smith nonetheless made the determination that his steed was ready for flight.

Smith executed a full afterburner take-off to the west. The fleet Super Sabre eagerly took to the air. Accelerating and climbing, the aircraft was almost supersonic as it passed through 35,000 feet. Peaking out around 37,000 feet, Smith sensed a heaviness in the flight control column. Something wasn’t quite right. The jet was decidely nose heavy. Smith countered by pulling aft stick.

The Super Sabre did not respond at all to Smith’s control inputs. Instead, it continued an uncommanded dive. Shallow at first, the dive steepened even as the 215-lb pilot pulled back on the stick with all of his might. But all to no avail. The jet’s hydraulic system had failed. As the stricken aircraft now accelerated toward the ground, Smith rightly concluded that this was going to be a short ride.

George Smith knew that he had only one alternative now. Eject. However, he also knew that the chances were quite small that he could survive what was quickly shaping-up to be a quasi-supersonic ejection. Suddenly, over the radio, Smith heard another Super Sabre pilot flying near his vicinity frantically yell: “Bail out, George!” So exhorted, Smith proceeded to do so.

Smith jettisoned his canopy. The roar from the airstream around him was unlike anything he had ever heard. Almost paralyzed with fear, Smith reflexively hunkered-down in the cockpit. The exact wrong thing to do. His head needed to be positioned up against the seat’s headrest and his feet placed within retraining stirrups prior to ejection. But there was no time for any of this now. Smith pulled the ejection seat trigger.

George Smith’s last recollection of his nightmare ride was that the Mach Meter read 1.05; 777 mph at the ejection altitude of 6,500 feet above the Pacific Ocean. These flight conditions corresponded to a dynamic pressure of 1,240 pounds per square foot. As he was fired out of the cockpit and into the harsh airstream, Smith’s body was subjected to a horrendous drag force of around 8,000 lbs producing on the order of 40-g’s of deceleration.

Mercifully, Smith did not recall what came next. The ferocious windblast stripped him of his helmet, oxygen mask, footwear, flight gloves, wrist watch and even his ring. Blood was forced into his head which became grotesquely swollen and his facial features unrecognizable. His eyelids fluttered and his eyes were tortuously mauled by the aerodynamic and inertial load of his ejection. Smith’s internal organs, most especially his liver, were severely damaged. His body was horribly bruised and beaten as it flailed end-over-over end uncontrollably.

Smith and his seat parted company as programmed followed by automatic deployment of his parachute. The opening forces were so high that a third of the parachute material was ripped away. Thankfully, the remaining portion held together and the unconscious Smith landed about 75 yards away from a fishing vessel positiond about a half-mile form shore. Providentially, the boat’s skipper was a former Navy rescue expert. Within a minute of hitting the water, Smith was rescued and brought onboard.

George Smith was hovering near death when he arrived at the hospital. In severe shock and with only a faint pulse, doctors quickly went to work. Smith awoke on his sixth day of hospitalization. He could hear, but he couldn’t see. His eyes had sustained multiple subconjunctival hemorrhages and the prevailing thought at the time was that he would never see again.

Happily, George Smith did recover almost fully from his supersonic ejection experience. He spent seven (7) months in the hospital and endured several operations. During that time, Smith’s weight dropped to 150 lbs. He was left with a permanently damaged liver to the extent that he could no longer drink alcohol. As for Smith’s vision, it returned to normal. However, his eyes were ever after somewhat glare-sensitive and slow to adapt to darkness.

Not only did George Smith return to good health, he also got back in the cockpit. First, he was cleared to fly low and slow prop-driven aircraft. Ultimately, he got back into jets, including the F-100A Super Sabre. Much was learned about how to markedly improve high speed ejection survivability in the aftermath of Smith’s supersonic nightmare. He in essence paid the price so that others would fare better in such circumstances as he endured.

It is possible that George Smith was not the first pilot to eject supersonically. USN LCdr Authur Ray Hawkins survived ejection from his stricken Grumman F9F-6 Cougar in 1953. Aircraft speed at ejection was never definitively determined, but was estimated to be between 688 (Mach 0.99) and 782 mph (Mach 1.16). In any event, the dynamic pressure and therefore the airloads associated with Hawkins ejection were less than half that of Smith’s punchout.

George Smith was thirty-one (31) at the time of his F-100A mishap. He lived a happy and productive thirty-nine (39) more years after its occurrence. Smith passed from this earthly scene in 1994.

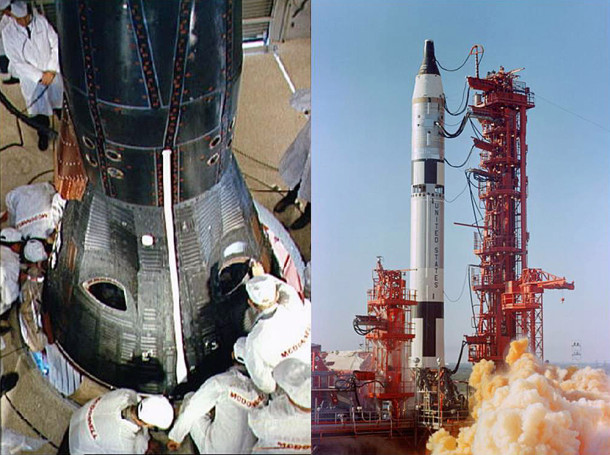

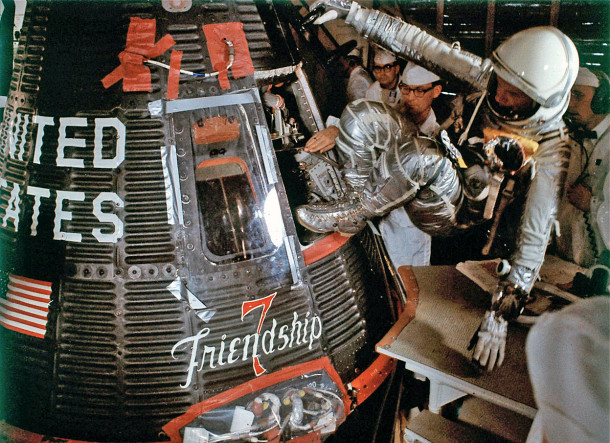

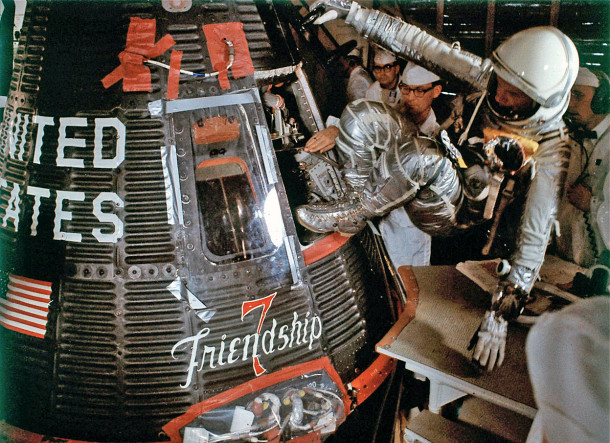

Fifty-four years ago this week, Project Mercury Astronaut John Herschel Glenn, Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Glenn’s spacecraft name and mission call sign was Friendship 7.

Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 14 at 14:47:39 UTC on Tuesday, 20 February 1962. It was the first time that the Atlas LV-3B booster was used for a manned spaceflight.

Three-hundred and twenty seconds after lift-off, Friendship 7 achieved an elliptical orbit measuring 143 nm (apogee) by 86 nm (perigee). Orbital inclination and period were 32.5 degrees and 88.5 minutes, respectively.

The most compelling moments in the United States’ first manned orbital mission centered around a sensor indication that Glenn’s heatshield and landing bag had become loose at the beginning of his second orbit. If true, Glenn would be incinerated during entry.

Concern for Glenn’s welfare persisted for the remainder of the flight and a decision was made to retain his retro package following completion of the retro-fire sequence. It was hoped that the 3 flimsy straps holding the retro package would also hold the heatshield in place.

During Glenn’s return to the atmosphere, both the spent retro package and its restraining straps melted in the searing heat of re-entry. Glenn saw chunks of flaming debris passing by his spacecraft window. At one point he radioed, “That’s a real fireball outside”.

Happily, the spacecraft’s heatshield held during entry and the landing bag deployed nominally. There had never really been a problem. The sensor indication was found to be false.

Friendship 7 splashed-down in the Atlantic Ocean at a point 432 nm east of Cape Canaveral at 19:43:02 UTC. John Glenn had orbited the Earth 3 times during a mission which lasted 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds. In short order, spacecraft and astronaut were successfully recovered aboard the USS Noa.

John Glenn became a national hero in the aftermath of his 3-orbit mission aboard Friendship 7. It seemed that just about every newspaper page in the days following his flight carried some sort of story about his historic fete. Indeed, it is difficult for those not around back in 1962 to fully comprehend the immensity of Glenn’s flight in terms of what it meant to the United States.

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. will turn 95 on 18 July 2016. His trusty Friendship 7 spacecraft is currently on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Seventy-one years ago this week, the Consolidated Vultee XP-81 made its flight test debut at Muroc Army Air Field, California with Vultee test pilot Frank Davis in the cockpit. The XP-81 was a prototype long range escort fighter powered by a combination of single turbojet and single turboprop engines.

The XP-81 was designed to serve as an escort fighter for long range bomber aircraft. Its mission was to defend bomber formations from attack by enemy fighters. To fly and fight, an escort fighter had to match the range and endurance capabilities of the much larger bombers it was assigned to protect.

The military wanted an escort fighter with an operating range of 1,250 miles and a maximum speed of 500 mph. Consolidated Vultee Aircraft (Convair) chose a bi-mode propulsion system to meet these requirements. The idea was to combine the excellent fuel economy of a turboprop with the high-speed capability of a turbojet. The turboprop was intended for cruise while use of the turbojet was reserved for takeoff and high speed flight.

The XP-51 was a big airplane by fighter standards. It measured almost 45 feet in length and had a wing span of 50.5 feet. Gross take-off and empty weights were 19,500 and 12,755 lbs, respectively. The type’s predicted range was estimated to be 2,500 miles at 275 mph and 25,000 feet. Service ceiling was rated at 35,500 feet.

Convair built a pair of XP-81 aircraft. Ship No. 1 (S/N 44-91000) and Ship No. 2 (S/N 44-91001) were completed in 1945 and sent to Muroc Army Air Field for flight testing. Ship No. 1 made the type’s first flight on Wednesday, 07 February 1945 with Vultee test pilot Frank Davis at the controls. With the exception of rather marginal directional stability, Davis found the handling characteristics to be quite good.

Testing of the XP-81 prototypes consisted of just 10 hours in the air. While the aircraft showed decent promise, the entire program was cancelled in May of 1947. With VE having occurred in May of 1945 and VJ in August of 1945, the need for a long range escort fighter simply went away.

Following program cancellation, the XP-81 aircraft served for a season as photo targets on the Bombing Range at Edwards Air Force Base. Eventually they were rescued from that inglorious state and sent to storage at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Forty-two years ago this week, the USAF/General Dynamics YF-16 Lightweight Fighter (LWF) took to the air on its first official flight with General Dynamics test pilot Phil Oestricher at the controls. The YF-16 would go on to win the Air Combat Fighter competition following a head-to-head fly-off with Northrop’s YF-17 Cobra.

The YF-16 was General Dynamics entry into the USAF Lightweight Fighter Program of the 1970’s. Its basic design was based on USAF Colonel John Boyd’s Energy Maneuverability (EM) Theory which posits that an aircraft with superior energy capability will defeat an aircraft of lesser energy capability in air combat. To achieve such, EM Theory dictated a small, lightweight aircraft having a high thrust-to-weight ratio, which permitted high-g maneuvering at minimum energy loss. The YF-16 was an embodiment of this requirement.

The official first flight of the YF-16 (S/N 72-1567) took place on Saturday, 02 February 1974 at Edwards Air Force Base, California. General Dynamics test pilot Phil Oestricher (pronounced Ohl-Striker) did the piloting honors. The nimble aircraft performed very well and was a delight to fly. Oestricher landed uneventfully following a brief test hop that saw the YF-16 reach 400 mph and 30,000 feet.

Interestingly, the real first flight (historically known as Flight 0) of the YF-16 inadvertently occurred on Sunday, 20 January 1974 during what was supposed to be a high-speed taxi test. As the aircraft accelerated rapidly down the runway, Oestricher raised the nose slightly and applied aileron control to check lateral response. To the pilot’s surprise, the aircraft entered a roll oscillation with amplitudes so high that the left wing and right stabilator alternately struck the surface of the runway.

As Oestricher desperately fought to maintain control of his wild steed, the situation became increasingly dire as the YF-16 began to veer to the left. Realizing that going into the weeds at high speed was a prescription for disaster, the test pilot quickly elected to jam the throttle forward and attempt to get the YF-16 into the air. The outcome of this decision was not immediately obvious as Oestricher continued to struggle for control while waiting for his airspeed to increase to the point that there was lift sufficient for flight.

When the YF-16 finally became airborne, it departed the runway on a heading roughly 45 degrees to the left of the centerline. Oestricher somehow maintained control of the aircraft during the rugged lift-off and early climbout phases of flight. The pilot then successfully executed a go-around, entry into final approach, and landing back on the departure runway. A tough way to earn a day’s pay!

History records that the YF-16 went on to win the Air Combat Fighter (ACF) competition with Northrop’s YF-17 Cobra. The production aircraft became known as the F-16 Fighting Falcon, of which more than 4,500 aircraft, in numerous variants, were built between 1976 and 2010. The now-famous aircraft has clearly fulfilled the measure of its creation as evidenced by its presence in the military inventory of more than 25 countries worldwide. Significantly, America’s Ambassadors in Blue, The United States Air Force Thunderbirds, have flown the F-16 in aerial demonstrations worldwide since 1983.

While its initial foray into the air did not necessarily lend confidence that such would be the case, the YF-16 did survive its flight test career. Aviation aficionados may view the actual aircraft at the Virginia Air and Space Center located in Hampton, Virginia.

Thirty years ago today, the seven member crew of STS-51L were killed when the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch from LC-39B at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The tragedy was the first fatal in-flight mishap in the history of American manned spaceflight.

In remarks made at a memorial service held for the Challenger Seven in Houston, Texas on Friday, 31 January 1986, President Ronald Wilson Reagan expressed the following sentiments:

“The future is not free: the story of all human progress is one of a struggle against all odds. We learned again that this America, which Abraham Lincoln called the last, best hope of man on Earth, was built on heroism and noble sacrifice. It was built by men and women like our seven star voyagers, who answered a call beyond duty, who gave more than was expected or required and who gave it little thought of worldly reward.”

We take this opportunity to remember the noble fallen:

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee, Commander

Michael John Smith, Pilot

Ellison S. Onizuka, Mission Specialist One

Judith Arlene Resnik, Mission Specialist Two

Ronald Erwin McNair, Mission Specialist Three

S.Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist One

Gregory Bruce Jarvis, Payload Specialist Two

Speaking for grieving families and countrymen, President Reagan closed his eulogy with these words:

“Dick, Mike, Judy, El, Ron, Greg and Christa – your families and your country mourn your passing. We bid you goodbye. We will never forget you. For those who knew you well and loved you, the pain will be deep and enduring. A nation, too, will long feel the loss of her seven sons and daughters, her seven good friends. We can find consolation only in faith, for we know in our hearts that you who flew so high and so proud now make your home beyond the stars, safe in God’s promise of eternal life.”

Tuesday, 28 January 1986. We Remember.

Forty-nine years ago today, the Apollo 204 prime crew perished as fire swept through their Apollo Block I Command Module (CM). The Apollo 204 crew of Command Pilot Vigil I. “Gus” Grissom, Senior Pilot Edward H. White II and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee had been scheduled to make the first manned flight of the Apollo Program some three weeks hence.

On Friday, 27 January 1967, during a plugs-out ground test on LC-34 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, a fire broke out in the Apollo 204 spacecraft at 23:31:04 UTC (6:31:04 pm EST). Shortly after, a chilling cry was heard across the communications network from Astronaut Chaffee: “We’ve got a fire in the cockpit”.

Believed to have started just below Grissom’s seat, the fire quickly erupted into an inferno that claimed the men’s lives in less than 30 seconds. While each received extensive 3rd degree burns, death was attributed to toxic smoke inhalation.

The Apollo 204 fire was most likely brought about by some minor malfunction or failure in equipment or wire insulation. This failure, which was never positively identified, initiated a sequence of events that culminated in the conflagration.

The post-mishap investigation uncovered numerous defects in CM Block I design, manufacturing, and workmanship. The use of a (1) pure oxygen atmosphere pressurized to 16.7 psia and (2) complex 3-component hatch design (that took a minimum of 90 seconds to open) sealed the astronauts’ fate.

A haunting irony of the tragedy is that America lost her first astronaut crew, not in the sideral heavens, but in a spacecraft that was firmly rooted to the ground.

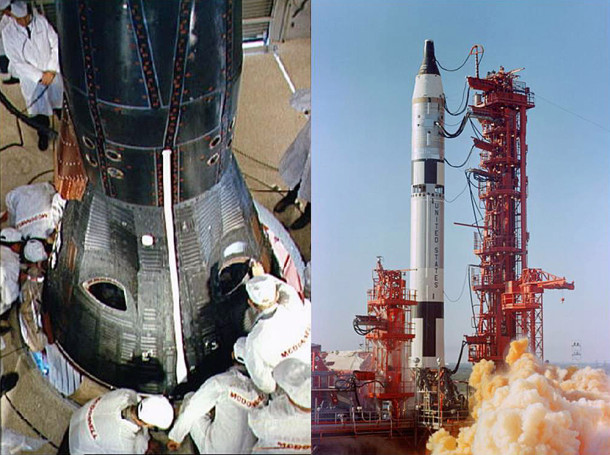

Fifty-one years ago to the day, NASA successfully completed the unmanned Gemini-Titan 2 (GT-2) space mission. The suborbital spaceflight served as a final test that cleared the way for the first manned Gemini orbital mission (GT-3) flown several months later.

The Gemini Program was America’s second manned space project. Gemini pioneered key technologies required to land men on the Moon including space navigation, rendezvous, docking, orbital maneuvering, long-duration spaceflight and extra-vehicular activity (EVA). Without Gemini, the United States would not have achieved the goal of landing men on the Moon before the end of the 1960’s.

The two-man Gemini spacecraft weighed 8,500 pounds at lift-off and measured 18.6 feet in length. Gemini consisted of a reentry module (RM), an adapter module (AM) and an equipment module (EM).

The crew occupied the RM which also contained ships’ navigation, communication, telemetry, electrical and reentry reaction control systems. The AM contained maneuver thrusters and the deboost rocket system. The EM included the spacecraft orbital attitude control thrusters and the fuel cell system. Both the AM and EM were used in orbit only and discarded prior to entry.

A two-stage Titan II launch vehicle served as the chariot that Gemini rode into space. Designed for the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) role, the native reliability of the Titan II had to be substantially improved for the vehicle to safely carry men into space. The history of spaceflight records that the man-rated Titan II truly fulfilled the measure of its creation by successfully launching ten (10) Gemini crews into earth orbit.

Gemini-Titan (GT-2) was the second and last unmanned flight test of the Gemini spacecraft. Since the primary goal was to flight-prove the craft’s heat shield performance during reentry, the mission was suborbital in nature. GT-2 lifted-off from Cape Canaveral’s LC-19 at 14:22:14 UTC on Tuesday, 19 January 1965. The vehicle’s arcing ballistic trajectory took it over the Atlantic Ocean on a flight that lasted only 18 minutes and 16 seconds. Maximum altitude and impact range were 92.4 nm and 1,847.5 nm, respectively.

Gemini 2’s ablative heat shield functioned as designed and came through the fiery reentry in excellent condition. Most of the spacecraft’s other flight systems performed satisfactorily during the vehicle’s brief sojourn into the heavens. Exceptions here included the fuel cell system which failed prior to lift-off and cooling system temperatures which exceeded design requirements.

Gemini 2’s splashdown point was situated approximately 45 nm from the USS Lake Champlain. About 90 minutes after splashdown, Gemini 2 was hauled aboard the recovery ship. Engineers found that the spacecraft came through the flight in such good shape that it actually flew a second suborbital reentry in November of 1966. Along with the OPS 0855 boilerplate spacecraft, the Gemini 2 reentry module was flown aboard a Titan IIIC launch vehicle in support of the USAF Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) Program.

The successful completion of GT-2 (along with the previous GT-1 orbital mission) provided NASA with the confidence needed to proceed with manned Gemini missions. The first of ten (10) such missions, GT-3, was successfully flown in March of 1965. A mere 20 months later (December 1966), the Gemini Program was brought to a successful conclusion with the splashdown of Gemini 12.

The Gemini Program was remarkable for its many significant and historic spaceflight achievements that paved the way to the moon. The brief mission of Gemini-Titan 2 was a small, but important part of that larger story. Today, aerospace aficionados can view the twice-flown Gemini 2 reentry module at the Air Force Space and Missile Museum, Cape Canaveral, Florida.